East of Art: Transformations in Eastern Europe: “Changing the Context: The Polish Experience”

I’m taking part in this panel as an artist – a practitioner participating in certain events, and not as a philosopher, a curator or an art critic, whose standpoint is characterized, among others, by objective judgment.

I will, for the most part, talk about events in which I participated myself, and things which I remember, some of which may be subjective. For this reason I will concentrate mostly on the situation in Poland, because that is where I studied, worked and, above all, where I mainly showed my work for the first few years – and not on the “Central or Eastern European” situation, with which I am not so familiar.

I began studying at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in the second half of the Eighties. The political and cultural situation in Poland at that time was an exceptional one. This was the period of martial law. Officially, it had already been suspended by 1983. Many repressive laws were still in place until 1989, and along with them, there was a good deal of oppositional activity, right up to the turning point.

So I was aware of the official professional boycott of almost all galleries financed by the State (particularly the large, representational ones). Well-known Polish artists did not show at these galleries and actors refused to appear on television so as not to lend credibility to the Communist system with their faces or their words.

A large segment of Polish cultural life was transferred – and I know it sounds improbable – to the church, which was, at this time the only official non-governmental institution, with its own structure, independent of the state. Many exhibitions, organized by independent curators, where held on church or parish premises at that time.

Both good and bad artists participated in these exhibitions (at that time there was no distinction between believers and non-believers, Catholics and non-Catholics), and there weren’t really any formal guidelines any censorship. Participation in this sort of exhibition was, first and foremost, a manifestation of one’s membership of the political opposition.

What counted was that the works were created “for the fortification of the soul” and were, for this reason, simply flat political illustrations with a hint of religious metaphor. So exhibitions were full of paintings of Christ on the cross- which was to symbolize the sufferings of Poland. Most of these works have not stood the test of time, they seem illegible, especially to those from outside of this historical and political context.

Alternative means of exhibitingat that time, were either in private studios and apartments (I have less experience of this as I was only a student starting out and was not yet established in these circles), or with small galleries such as Foksal, which were subsidized by the State but had the respect of critics and artists, galleries with contacts in the outside world which promoted art approaching the Conceptual and the avant-garde.

Both these options, as apposed to the church exhibitions, were very hermetic and only accessible to a small group of people. I only went to Foksal once at that point and was put off by a certain atmosphere of “swank’ness”, and what was, for me, a false sense of “sacredness.”

I ought to mention something rather obvious: There were no private galleries in Poland then, there was no art market, there were virtually no art journals, and the opportunities for traveling to the West were few (for political but also financial reasons). So the “average Polish intellectual’s” only contact with contemporary art was through the church exhibitions, which were, with their illustrative and militant vocation ideally suited to the kind of art reception that had historically already developed in Polish art (art as a certain addition to history and literature, rather than as a separate value or sphere).

The years 1989-1990 represented, above all, a political breakthrough (the opposition’s accession to power) and an economic one. By then I was studying under Grzegorz Kowalski, in his sculpture studio. He was probably the only one at the Academy of Fine Arts at that time to have a very personal approach to students and he taught us not so much technique, as he allowed us to experiment and encouraged us to search for our own language.

We were already an active group of students, creating interesting, perhaps even truly “controversial” work, although basically working in a safe vacuum. Society – that is to say our future audience was busy with the “wild economic transformations” and had lost interest in art.

A small number of enthusiasts – such as the businessman and “art-lover” Andrzej Bonarski on the slide here had hopes, that it would be possible to develop an art market. He hoped that by organizing independent exhibitions (reminiscent of the church ones in spirit and appearance, only this time held in rented premises and factories) he would be able to persuade businessmen to buy contemporary works of art and create demand and that things would take off from there.

But it didn’t take off. One system of financing art – the Communist one – had vanished, but no other system developed. For several years artists were working in a complete void, with no public interest, no media interest, without even the interest of critics, who were a few steps behind what was happening in art among young people.

It seems to have been my degree show at the Academy of Fine arts, the exhibition of the “Pyramid of Animals” that broke this silence. “The Pyramid of Animals” is an installation made of stuffed animals: a horse, a dog, a cat and a rooster-one animal standing on top of the other.

Formally, it is a reference to the Brothers Grimm fairy tale “The Musicians from Bremen”, which is the story of some old animals – a donkey, a dog, a cat and a rooster who have been thrown out by their owners when they ceased to be of any ‘use’. I replaced the donkey with a horse (the horse has more cultural connotations in Poland).

A statement saying that I selected the animals when they were still alive, but already sentenced to death accompanied the sculpture. I also admitted that I had shot a video documentary witnessing the putting down, skinning and gutting of the same horse people can recognize in the Pyramid.

That video later replaced the written statement and was shown together with the pyramid. The journalists caught on that this might be a hot ticket – a heated debate which might grab the reader’s interest and cause a stir. The topic was taken up by one of the TV stations and by most of the papers.

I was accused of “killing an animal for the sake of art”. Everybody protested: artists, celebrities, journalists and ordinary people. They all felt obliged to comment on it. It didn’t matter that none of them had seen the piece and only knew of its existence from the TV or the press. The Association of Polish Artists demanded that the Rector of the Academy of Fine Arts withdraw my degree.

I wasn’t allowed to speak in public to defend myself or explain why I had come to make the sculpture. I was entirely alone and my only defender was my Professor, G. Kowalski. Art critics, even those who specialized in contemporary art, didn’t defend me. They too found the work shocking, and didn’t know what to make of it.

I think it would be safe to assume that it was thanks to the Pyramid that they had to find out, to learn. The press labeled me a scandalmonger, and it was in these terms that it greeted each of my subsequent works. So a certain interest in art came into existence, although in rather a twisted way – as scandal.

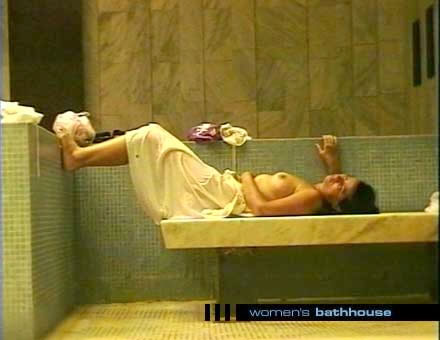

But I think it was this that mobilized critics, because when I came to show my next works – Olympia, the Women’s Bathhouse and the Men’s, I could count on a degree of understanding (a degree of attempts to understand) on their part. Still, this didn’t really translate into the press because they didn’t really have anywhere to write it.

Katarzyna Kozyra, “Women’s Bathouse” (partial view of the installation), 1997

In order to show clearly the kind of boundary represented by the Pyramid of Animals, not just for me but for others too, I’d like to show two short fragments of film. One by Zbyszek Libera, made between 1984 and 1986-so a lot earlier-entitled “Intimate Chores”.

The artist filmed himself looking after his old, helpless grandmother. The other one is from 1997, so over ten years later, a fragment from my video installation “Women’s Bathhouse.” I shot the footage for the “Womens’ Bath” in a public bath in Budapest using a hidden camera. Libera has shown his film on numerous occasions, both in non-official, social circuits, and, after ’89, at several official exhibitions.

This film was never mentioned in the press, caused no scandal, and was not widely commented on. The critics (as they did with the Pyramid) again felt helpless when faced with the task of interpreting it. But the Bathhouse is the work that became a media incident. And as in the case of the Pyramid of Animals, here again, the reasons for the criticism it received went beyond the realm of art. Reading the press articles one finds that, even when it is ethics being discussed, in fact, if we keep reading, it turns out this is just a cover, and that what is really under fire is the lack of aesthetics.

The press wrote about the woman being unattractive and accused me of provoking indignation with hideousness and old age… with “ugly bodies without heads” (as if peeping at models were justified). “Poles are mocking Hungarian women”, a Hungarian Journalist reported, trying to penetrate the international significance of the affair. Because, after all, can there be any other reason, if not to mock them, for showing women in their natural state, not as they are expected to be seen?

Exactly the same accusations could be leveled at Libera (lack of ethics, or aesthetics), but when this film was being made the ball was in another court: primarily in the political one – Communism and the Opposition. Besides, critics, without much knowledge of Foucault, Lacan, or even feminist criticism, didn’t yet have the tools to interpret this great work (which is one of the artist’s strongest).

|  |  |

Zbigniew Libera, From “Intimate Chores” (1984-1986)

Neither was it, at that time, a subject for the press. AND, as was clear, for example, from the work’s last showing, at a group exhibition at the Zacheta Gallery last year – it still isn’t today. The predicament of art now (since the Pyramid) and since the 1990’s, is a bit different.

What has changed for the better? There is a greater interest in art among critics and art historians. There are slightly more specialist journals (especially on the internet), more galleries and independent exhibition spaces.

What has not changed at all? The almost total lack of a contemporary art market in Poland. Despite efforts, the creation of some new way of financing art remains impossible. Proposing tax deductions, money from the national lotteries and similar ideas all fail. Also impossible, is the creation of a Museum of Contemporary Art, or even ensuring that the National Museum has a permanent exhibition devoted to art since 1945.

What has gotten worse? The scandals provoked by art have shown certain politicians that a work, an artist, can be a tool for gaining broad popularity – that the papers, the press are all too pleased to show – on their front pages or on prime time TV – a politician (even a minor one), protesting in front of some work of contemporary art.

Especially if the work in some way touches on the CATHOLIC religion (or can be interpreted as relating in some way to it). So what we get are “false scandals”, conducted politically, using works and artists. The situations that result are often dangerous, but also amusing.

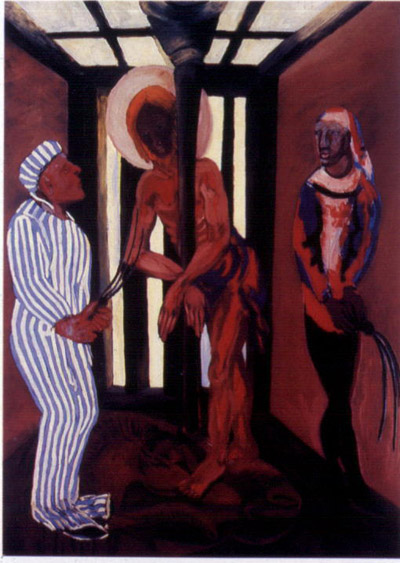

Here you see a work by the Polish painter Marek Sobczyk from 1987, entitled “The Flagellation of Christ.” This painting was, in 1989, purchased for the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw, without any controversy! In 2001, when shown at the exhibition “Irrelogia” in Brussels, it was interpreted by the Catholic press as a painting, which was an insult to the Catholic religion, and accusations were leveled at the work (and the artist) that they were offensive to religious values.

There are more and more such instances. Last year was the first time that such an incident went to court, and the young artist Dorota Nieznalska was brought to trial for her installation “The Passion”, and stood officially accused for offense to religious feelings.

Dorota Nieznalska’s “Passion” is an installation consisting of photographs of male genitals on the cross, and a video of men working out at the gym. Thus far there have been three court hearings and several dozen witnesses have been heard (mostly from the prosecution).

What I find strange is that artists find no “natural allies”, neither among the liberal left, nor among intellectuals. I find the situation paradoxical: That the intensification of such “anti-art” protests and the first case to be tried in court should be in full swing when the government is a left-wing one. The next trial against the young artist will be at the end of April, and the judge’s decision will set a precedent.

To end, I would like to show a fragment of a work, a video by Artur Zmijewski, with whom (along with Pawel Althamer) I studied under Grzegorz Kowalski. The video is called “The Singing Lesson” and is from 2002. Zmijewski filmed mute people trying to sing a piece by Bach. Above all, it’s an excellent piece of work, with its own interpretation. All the same, I would like to “use” it a bit – as a kind of metaphor for the situation in Poland, which I have been describing.

March 23, 2003

© Museum of Modern Art, New York

[su_menu name=”East of Art”]