Collaborating with Wind, Water, and Time – Saodat Ismailova

The year 2023 saw two retrospective exhibitions of the work of Saodat Ismailova: Double Horizon at Le Fresnoy-Studio National (February 10 – April 30, 2023), which was the culmination of the artist’s two-year residency at the School of Contemporary Art in Tourcoing, and 18,000 Worlds at Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam (January 21 – June 4, 2023), which accompanied the Eye Art & Film Prize the artist received for her work interweaving contemporary art and cinema. A year earlier, the artist left her mark both at the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale, and at the documenta fifteen exhibition in Kassel, Germany. With these major shows Ismailova, who was originally trained as a filmmaker, made a quantum leap within the art world.

Yet this accelerated exposure of Ismailova ’s work to international audiences has had little to do with the pace of her own artistic practice, which embraces slowness and concentrated scrutiny. Her work emerges from the specific geographical and historical context of Central Asia, and draws on the region’s vernacular cultures and modes of living and thinking. Born in Tashkent in 1981, Ismailova studied documentary and fiction film at the Uzbekistan State Institute of Arts. Film culture was something she was exposed to early on, as her father Adurakhim Ismailov, was a renowned Uzbek cinematographer. It is also in cinema that she made her debut with the documentary Aral, Fishing in an Invisible Sea (2004), made with Carlos Casas, followed by the fiction film Chilla, 40 Days of Silence (2014). Since 2004, Ismailova has lived and worked in Europe: first in Italy, where she joined Fabrica art research center for a residency in 2004, then in Spain and France. With Zukhra, shown at Venice Biennale in 2013, she made her first appearance in the contemporary art context. This work introduced the themes that permeate the exhibitions at Le Fresnoy and The Eye Filmmuseum. Drawing upon Uzbek and Central Asian cultures, the artist develops a pensive, visually engaging, collaborative practice in an exploration of the region’s multilayered realities. Women’s histories and modes of being play a significant role in her practice – especially feminine modes of knowing which, in Central Asia, are transmitted matrilineally. She also engages with the larger-than-human actors and ecological issues of the region, reviving ideas of animism and shamanism. Ismailova ’s work has the intensity and concentration that gives these familiar themes a sense of momentum.

Saodat Ismailova. Double Horizon. Exhibition view at Le Fresnoy-Studio National, February 10 – April 30, 2023. Image courtesy of Le Fresnoy. Photograph by Richard Baron.

The exhibition in Tourcoing centered around two new film installations produced by Le Fresnoy – Two Horizons (2017) and Stains of Oxus (2016) – and showed them, together with four other major works by Ismailova, against a selection of works by about twenty other artists, including those from the region of Central Asia such as Chingiz Aidarov, Vyacheslav Akhunov, Yelena & Viktor Vorobyev, Muratbek Djumaliev & Gulnara Kasmalieva, as well as artists dealing with related themes, among them Mona Hatoum, Fiona Tan, Zineb Sedira, Joseph Beuys, and Henri Michaux. The presence of these internationally renowned artists favored broad comparisons and multidirectional connections, embedding the Central Asian art scene within a recognizable artistic landscape, whether it be in the context of alternative spiritualities explored by Beuys and Michaux, or the feminist and migratory tales told by Hatoum, Tan or Sedira. The exhibition also included the so-called Suspended Laboratory with a selection from the artist’s archives along with Ismailova’s earlier documentary audiovisual research into Central Asian dance and music traditions – a segment of her work which is lesser known, but which clearly informs her more recent, large-scale installation pieces and provides more historical, political, and social context.

The exhibition in the Eye Filmmuseum was focused more prominently on Ismailova ’s own large-scale installations, including Chilltan #1 (2020) consisting of forty chachvon, a face-covering veil worn in Uzbekistan, and the newly made film installation, 18,000 Worlds (2022) which gave the exhibition its title. While no other artists were present in the show, the accompanying program comprised a virtual screening of Central Asian film and video, which could be seen online for the duration of the exhibition. The screening program can be seen as a continuation of Ismailova’s project for documenta fifteen, during which she initiated the Davra collective of Central Asian artists. The documenta’s concept of lumbung, which stands for sharing resources and spreading cooperative art culture, seems central in her own artistic endeavors, encompassing not only working together with other artists or art workers, but also drawing on collective memory and myth as sources of ancestral knowledge. This ancestral connection eventually reveals itself to be expanded to include alliances with more-than-human actors.

Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds, January 21 – June 4, 2023, Exhibition view at Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum. Photograph by Studio Hans Wilschut.

Abandoned futures of socialism and shamanism

The immense, flat landscape of the steppe emerged as one of the defining features of the two exhibitions, describing the specific natureculture, to use Donna Haraway’s term, of the complex and rich area known geographically as Central Asia.(Donna J. Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003).) The all-present steppe wind appears repeatedly on the large screens, blowing through the small pieces of fabric tied to the pole structures found in Kazakhstan, which are visible in several videos. At Le Fresnoy, it also features prominently in the installation Desert of oblivion. Wandering Sands (Dunes) (2000) by Vyacheslav Akhunov, quite literally made of sand and evoking human displacement after the collapse of the Soviet Union – connecting the shapes of the landscape to the movement of people.

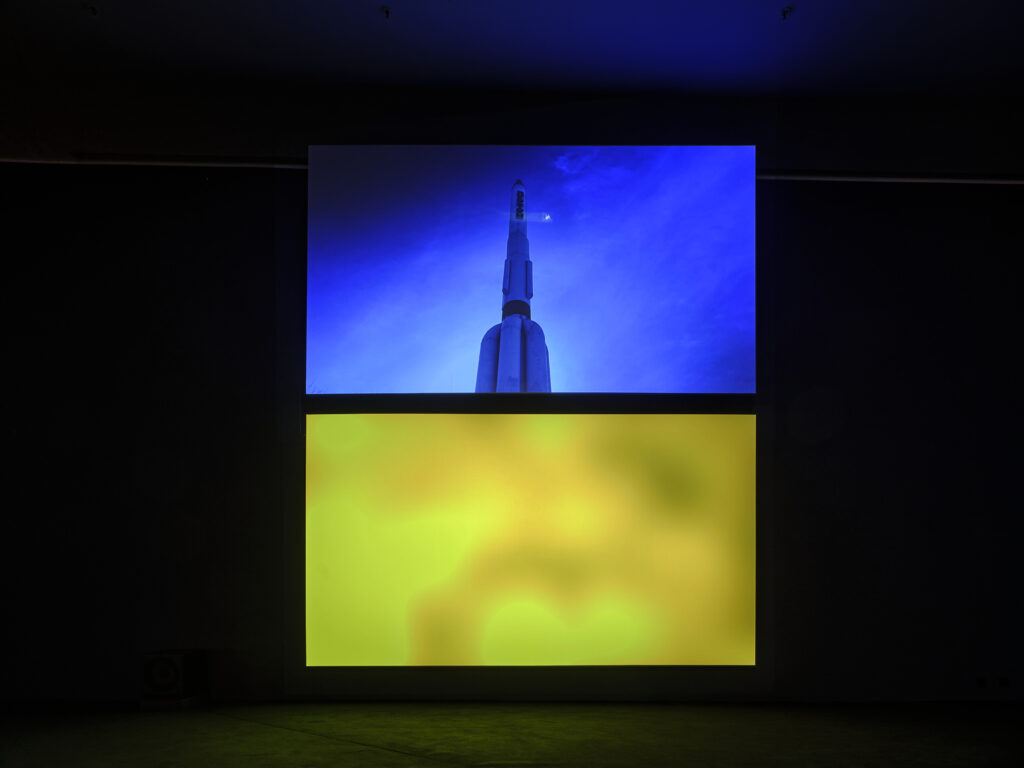

Ismailova’s double-channel installation Two Horizons (2017), consisting of two screens placed vertically one on the other, is the most striking articulation of the entwinement of the cultural and environmental elements of the landscape. At the same time, this piece introduces the idea of an affinity between its different historical moments. It might seem unlikely that bringing the Soviet past and shamanist mythology together in one narrative can yield anything but disparity and contradiction. Two Horizons takes as its point of departure the historical layering of these incommensurate worlds in the vast, flat landscape of the Kazakh steppe. Filmed at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, a “gift of modernity” built by the Soviets in 1955 – just twenty kilometers away from the ancient cemetery of Korkut – it ties the oral history of the legendary shaman of the Turkish world to the space exploration program advanced at the height of the Cold War.(Maria Sarkulova and Roza Khassenova, “Cosmodrome as a ‘Gift of Modernity’: Representation of the Theme of Space in Kazakh and Kyrgyz Literature.” Trames 26, 76/71, no. 4 (2022): pp. 413-26.) The blue-tinted steppe landscape – a visual signifier of either the early morning or the late evening –reveals, in a slow camera movement, the quest of a small boy searching for signs on the earth and in the sky. While no explanation is given, it can be assumed the boy is on a kind of spiritual journey. The narrative becomes an opportunity to weave together a reflection on the region’s past not in the habitual historical perspective, but from the point of view of human aspirations. It centers on the desire by the mythic 10th century shaman Korkut to achieve the state of levitation, which for him as for his contemporaries equaled conquering death. The Soviet space program, driven as it was by the ideological struggle of the Cold War and the modern imperative of progress, resulted in the successful mission in 1961 to send the first human to journey into outer space. The desire for vertical elevation – away from the ground and away from the linear passage of time – found its expression in these two distinct attempts at overcoming human limitations.

Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds, January 21 – June 4, 2023, Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibition view of Two Horizons, 2017. 2 channel HD video installation, 24 min., colour, 4.1 surround. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum. Photograph by Studio Hans Wilschut.

Ismailova filmed both sites as if they belonged to one tale, thus finding an improbable common ground for these otherwise incongruent times and worldviews. The locations appear not so dissimilar: the futurist architecture of the Baikonur cosmodrome, itself echoing the ancient mounds in its simple, geometric, and highly symmetrical forms, matches the aesthetic of the late Soviet monument erected on the site of the Korkut cemetery in the 1980s. The camera’s point of view shifts from the ground to the air. Drone-captured images scan the landscape from above to give a distant, vertical view, something which is usually associated with the abstract and disembodied perspective of technology and progress. Yet here this top-down view could also be reinterpreted as showing the perspective of one who has achieved the state of levitation. At some point the boy, who is perhaps a contemporary heir to the shamanistic tradition, sees beams of mysterious light rising from the ground. If the boy seeks spiritual awakening, the lights can be interpreted as the mystical energy that finds him. But in terms of the filming process, the mysterious light arising from the ground on the distant horizon is an actual launch of a space rocket at Baikonur – which is still in use today – and which Ismailova captured accidentally in 2017.(Marente Bloemheuvel, ed. Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds (Amsterdam: Eye Filmmuseum & Nai010, 2023), p. 89.) The documentary approach, with which the artist started her international career in 2004, is never far away. In her signature style, Ismailova seamlessly weds the historical moment and the arcane visions that surround it.

Story collector of entangled worlds

Documenting reality at hand remains central to Ismailova ’s work, yet it would be difficult to confine her practice to what is habitually understood as documentary film. Rather, she develops an entirely distinctive, expanded form of filmmaking, which bypasses the default visual and institutional regimes of documentary and fiction. Two Horizons originated from a story Ismailova was told by an elderly visitor to the Korkut cemetery in Kyzylorda, Kazakhstan, where she stayed for research and filming in the context of another project. This and other similar encounters made her develop the serendipitous story collecting into a method. Stains of Oxus (2016), produced by Le Fresnoy and shown in both exhibitions, emerged as one of the remarkable results of that methodology. The three-channel monumental video installation was filmed on a journey along the river Amu Darya – called Oxus by the Ancient Greeks –which zeroed in on people’s dreams told on its banks. Across its length of 2400 kilometers and traversing four Central Asian countries (Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), the river becomes the main character of the video, as it is witness to an ancient tradition common to all the people living in its watershed. When troubled by vivid dreams, the denizens of Amu Darya area visit the river in the morning and recount their dreams. Ismailova collected these dreams and stories, retelling them in the voice-over audible against the backdrop of the changing landscapes of the snowy Pamir mountains, industrialized valleys, and eventually the area of Amu Darya’s mouth running dry into the remnants of the now almost completely desiccated Aral Sea.

Strikingly, the dreams people share with the artist pertain not only to their personal lives and experiences, but also to the collective memories of the past. The basic strategy developed by Ismailova became akin to the history writing from below – not unlike that developed by the chronicler of the Soviet past Svetlana Alexievich who gathered histories of children, women, and little-known bystanders of the grand history. Yet while Alexievich collects ‘factual’ histories of her interlocutors, Ismailova does not shy away from other, unlikely historical resources such as people’s dreams. In the region of Central Asia, dreams are seen as a way of accessing knowledge passed on from ancestors, whether human or not. At the now desert-like landscape of the Aral Sea, the water itself lives only in dreams of the inhabitants trying to survive after the source of their subsistence died out. One of the people whose voice is recorded in the installation recalls that he still hears the sound of the sea water in his dreams although the actual sea is long dead.

Another recurrent visitor in the people’s dreams is the Turanian tiger – a species now extinct due to the extractive policies of the Soviets, but which was considered sacred in vernacular cultures. One of the dream-tellers describes how the tiger is their ancestor who guides them in their daily life. The frequent appearance of the tiger in the myths and rites of the inhabitants inspired Ismailova in the making of another film, The Hunted (2017), which is built around an intimate and impassioned letter to the animal, whispered by a female voice. The tiger appears to live on after its extinction, being remembered and respected by its human kins. Its repeated visits in people’s dreams, and other anecdotes passed on and sustained by the tradition of dream telling, appear as a precious and scarce source from which to recover the disappearing memory of the past. Indirectly, this collection of accounts, deeply related to the land and water defining people’s living conditions, becomes a way of rewriting histories of the region and reconceptualizing history itself.

Saodat Ismailova. Double Horizon. Le Fresnoy-Studio National, February 10 – April 30, 2023. Exhibition view of Stains of Oxus, 2017. 3 channel HD video installation, 24 min., 4.1 surround. Image courtesy of Le Fresnoy. Photograph by Richard Baron.

Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds, January 21 – June 4, 2023, Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibition view of The Haunted, 2017. HD video installation, 23 min. 30 sec, colour and black & white, stereo. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum. Photograph by Studio Hans Wilschut.

Inevitably, these works revisit the devastating memory of colonization, exploitation of land and the destruction of cultures in the region. The deep transformation of the environment and its effects on the inhabitants come to the fore as the recurrent theme of the dreams. While the film installation does not address in any direct way the grand irrigation projects (which dried out the river and the Aral Sea), or the cotton monoculture introduced in the region by the Soviet regime, it demonstrates very vividly the long lasting, calamitous effects of these modernization projects. The patient and observational camera movement as well as the attitude of listening propounded in this work contribute to an atmosphere of silent resistance rather than militant critique and accusation. Ismailova tunes in to the acts of resilience and coping strategies rather than dwelling on what is irretrievably lost.

Intimate and collective mythologies(The phrase “intimate and collective mythologies” is borrowed from Samira Negrouche, “Dans Chaque Marche D’escalier,” Correspondance. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay et Samira Negrouche (2023), https://doi.org/https://www.rot-bo-krik.com/correspondance-azoulay-negrouche.)

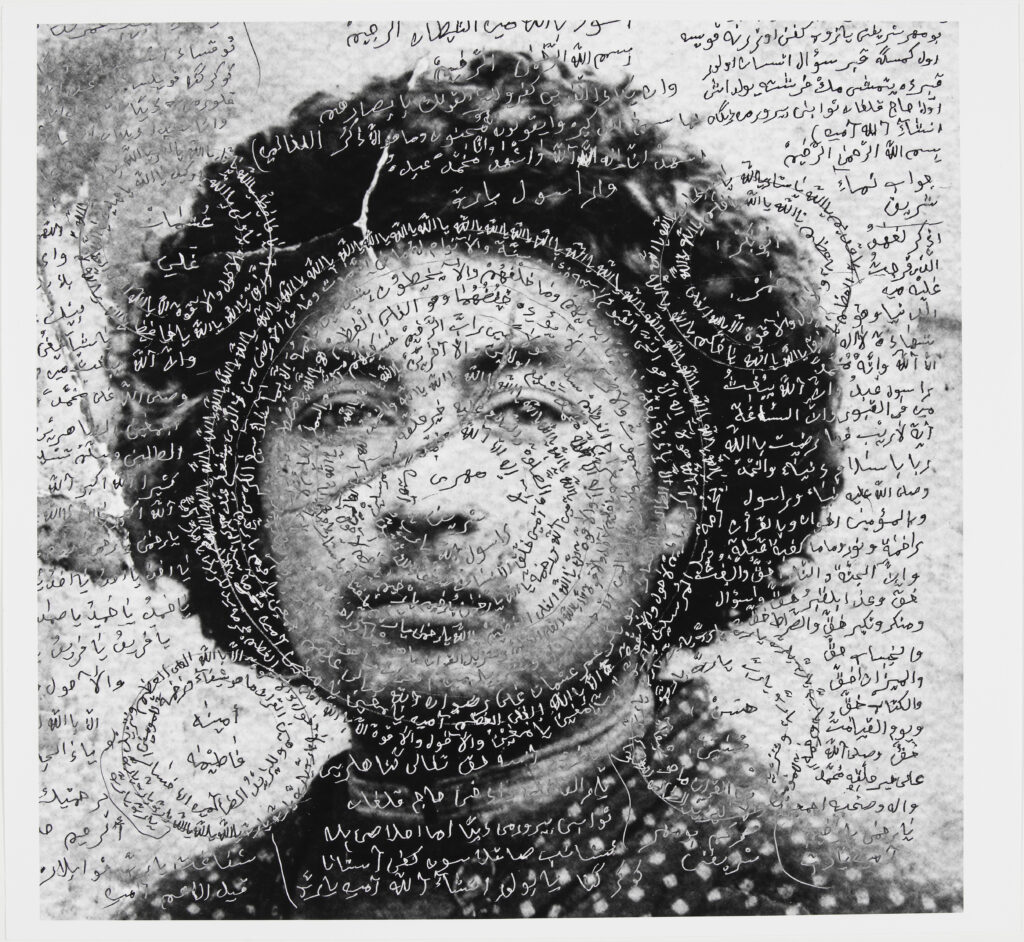

In the photographic series entitled The Letters (2013-2019), Ismailova used photographic portraits belonging to her family album and superimposed them with texts handwritten by the same people shown in the images. Displayed in both exhibitions (although in a slightly larger selection at Le Fresnoy), this series forms a genealogy that begins with the artist’s great-great-grandmother and concludes with her daughter. Her great-great-grandmother, pictured on the first portrait, was a teacher of Persian and Uzbek poetry. The text superimposed on the image is a poem by an 18th century mystic, which she transcribed by hand and passed on to her grandchildren.(Bloemheuvel, p. 55.) The second photograph is of the artist’s great grandfather as a young intellectual, who would soon be deported to the gulag as punishment for the knowledge he possessed, and which was considered threatening to Stalin’s desire for inflexible power. The impressively complex, partly circular, and highly symmetrical inscription appearing on his photograph is a written amulet. This inscription is no longer legible for a contemporary reader and needed to be deciphered with the help of scholars and knowledgeable elders. The amulet is written in Arabic alphabet, but the languages are Persian, old Uzbek and Arabic. The series thus becomes a testimony to the drastic changes in the languages and cultures of Central Asia. After the colonization by Russia and subsequently the Soviet Union, the alphabets and languages of the vernacular cultures were suppressed and people were often forced to move, resulting in the changing mosaic of languages visible even within the history of just one family. The subsequent photographs show the grandmother, mother and daughter of Ismailova, while their hand-written inscriptions reflect these cultural and linguistic changes – they are thus written in Arabic, Russian-Cyrillic, and French. Surprisingly perhaps, the language is sometimes different than the alphabet used, indicating that the sitters had restricted access to education. At times when only Russian-Cyrillic could be taught at school, they continued using vernacular languages at home, even if acquiring written skills was not possible. These inscriptions thus also witness to the resourcefulness of the people who were constantly forced to adapt to new linguistic norms. The artist’s family history speaks of far-reaching political upheavals of the last century by amplifying individual people’s endurance and resilience.

Saodat Ismailova. The Letters, 2014-2017, Centre Pompidou, copyright MNAM-CCI RMN-GP. Image courtesy Le Fresnoy. Photograph by Hélène Mauri.

It is from this recollection of her own, her family’s, and the larger community’s past, that Ismailova weaves her version of history. Private memories and family memorabilia become tokens of a shared past. This linkage of the personal and the collective – in The Letters running from the particular to the communal – can also move in the opposite direction. Zukhra (2013), the first video installation Ismailova showed in a contemporary art context, is built on a story of a girl disappearing in mysterious circumstances. As Ismailova mentioned in an interview, the story became an occasion for her to reflect on her own trajectory and sketch a kind of self-portrait by other means, without giving any direct clues towards her own life in the installation itself.(Ismailova stated this in a conversation with Marcella Lista at Centre Pompidou, March 23, 2022.) Visually, the video is highly concentrated – the framing is limited to one point of view and remains almost entirely static. It shows a bed in a traditional Uzbek house on which a girl is seen reclining, such that it is unclear whether she is sleeping, daydreaming, or whether she is dead or dying. This relative paucity of the visual input allows to shift the emphasis on the soundtrack consisting of a collage of night noises, recordings of rituals, whispered formulas, snippets of music, and at some point, also particularly distressing sounds of howling. These can again be perceived as ‘documentary’ recordings, relaying significant findings of Ismailova concerning Uzbek traditions of healing and exorcism. These recordings are simultaneously significant for her personal life, conveying a sense of a dead end and a need for healing she experienced after the making of her first fiction film Chilla. The video refers, even if indirectly, to the custom of forty days of silence – explored in that debut film – in which women vow to remain silent for the period of forty days to cure illness, especially mental illness or distress, which has traditionally been understood as a state of being possessed by spirits. The howling sounds in the video are from an actual exorcism ritual in which shamans imitate animal howling. The vow of silence itself is a form of withdrawal from public life and from human interaction, which can be seen as a way of recovery but also a sign of refusal. Ismailova conducted extended research on this disappearing tradition and included it in various works. Especially when practiced by women, the vow of silence can be interpreted as a powerful exercise in resistance.

Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds, January 21 – June 4, 2023, Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibition view of Zukhra, 2013. HD video installation, 30 min., colour, stereo. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum. Photograph by Studio Hans Wilschut.

Several of Ismailova ’s works center around women. Chillahona (2022) deals again with the ritual of self-isolation. In a three-screen installation, shown in Tourcoing, a woman enters a small underground dome used traditionally for this ritual and called chillahona. Chillpiq (2018), shown in Amsterdam, is a video installation of a performance the artist staged with forty young women reenacting an ancient ritual in the ruins of a prehistoric edifice in Uzbekistan. The found footage film Her Right (2020) is a mesmerizing collage of different images of women culled from fiction films made in the period of the Soviet Union and after its collapse. The main theme of the early films was the emancipation of women, which was communicated visually through the gesture of unveiling. While presented as a gift to women which would allow them to benefit from the modernization project, the forced unveiling, as designed by the Soviets, was rather a tactic of making women leave the private sphere and thus become available for collectivized labor in the cotton industry. Ismailova ’s personal collection of chachvon or traditional veils which she transformed in the monumental installation Chilltan #1 (2020) is a way of looking back at this history and addressing that which was supposed to be completely erased. This is not so much to return to some historical stage or period, but rather to uncover the obliterated aspects of that past which nevertheless reverberate in the present. In the convoluted history of women’s emancipation, the veil is but the spectacular sign of a larger set of issues among which access to knowledge and education are central. Yet the understanding of what knowledge itself is or can be, is not given, but is rather something to care for and to repair. The depleted idea of a totalizing and rational knowledge system imposed by (the Soviet version of) modernity is actively reconfigured throughout the two exhibitions. It is women who, in Central Asia, were guardians of certain forms of knowledge – such as healing practices and awareness of human-to-more-than-human connection – which were threatened and denigrated with the advent of the colonial modern.

Parts of this knowledge might never have been confined to books – a fortunate circumstance which probably saved it from oblivion as books can be burned and censored. Instead, it was whispered from ear to ear in the safety of the domestic space. Books are always present in Ismailova ’s work, appearing in the vitrines in both exhibitions as the material that assists her in her personal research process, be it recent scientific investigations or early ethnographic explorations by Russian and then Soviet scholars. But these books are confronted with and supplemented by the lived experience and the ephemeral knowledge passed on orally, in rites, dreams and practices such as poetry, storytelling and music. The latest video installation seen in the Amsterdam exhibition, 18,000 Worlds (2023), which was made especially for the Eye Filmmuseum, evokes this matrilineally transmitted and whispered knowledge. Based on an idea circulating in the region and written down by the poet and philosopher of Iranian Sufism Shihab al Din Shrawardi (1154-1191), the video tells of the existence of 18,000 parallel worlds, of which the one we inhabit is just a small rendering.

It is a meditative and experiential video accompanied by a suggestive soundtrack in which rapid montage of disparate images interlaces long and slow takes of landscapes and cityscapes and highly tactile close-ups. Time itself reappears here as that which is searched for but always elusive. Yet the existence of the many simultaneous worlds opens the potentiality of extending and circumscribing measured time. In several of the disparate sequences, an archeologist or restaurateur who, accidentally or not, is a woman, is shown slowly and painstakingly reconstructing an ancient painting, not intimidated by the loud ticking of a clock in the background. Landscapes of the steppe, mountains, factories, and cities, sleeping women and silent girls, appear in the montage as those who seem to speak in the voice-over while simultaneously being addressed by it. The whispered message speaks, more directly than any other of Ismailova ’s works, of this attitude of perseverance and resilience in the face of past and present attempts at the erasure of naturecultures, traditions and ways of living. As the voiceover suggests, the parallel worlds will come to the rescue, will mirror the disappearing worlds and repeat the cry of the silenced. It is here that Ismailova rediscovers, again, the ‘we’ who speaks from the shared wisdom and matrilineal knowledge. Several passages of the whispered address are not translated, testifying to the conviction that some knowledge must remain restricted, like a veil that should not be lifted, unless it is on the wearer’s terms.

Saodat Ismailova. 18,000 Worlds, January 21 – June 4, 2023, Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibition view of 18,000 Worlds, 2022. HD video installation, 23 min., colour and black & white, stereo. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum. Photograph by Studio Hans Wilschut.

The two exhibitions might at first glance be perceived as largely overlapping, but when examined more closely it is apparent that each gives a distinct insight into the artist’s work, offering two perspectives complementary to each other. The exhibition in Tourcoing builds a larger context of art practices which can be aligned with Ismailova ’s own explorations. By showing, for example, a sound installation by Deimantas Narkevicius The End of Censored Cinema, Again and Again (2011) – which recovers vernacular musical instruments from Lithuania and presents them through the sonic system produced by the Soviet industry –it not only allows the parallels between the works to become apparent, but also accentuates the importance of sound and music in Ismailova’s approach. The inclusion of artists from different regions of the world, on the other hand, unhinges her artistic practice from its geographic specificities, thus lifting the oversimplified label of a ‘typically’ Central Asian artist. It demonstrates that her work, while very particular, easily enters a conversation with artists from distant parts of the world. The exhibition in Amsterdam, on the other hand, allows similar parallels to be drawn not outside, but within Ismailova ’s oeuvre. Each of her installations shows itself as having a distinct theme, yet there are visual and sonic elements that bind these installations together. Showing them in one integrated space – as was the case in Amsterdam – allows for these parallels to come to the fore. The artist uses and reuses both found footage and objects as well as her own archives, as is apparent in the reappearance of the wooden construction with small pieces of cloth blown by the steppe wind in Chillpiq and The Hunted. The installations thus emerge as phases or stages in an ongoing exploration, of which 18,000 Worlds is the most recent articulation.

Through these different, rich, and intensely researched works, Ismailova not only recovers but also actively performs the important role women played in Central Asia – that is, knowledge transmission. This knowledge breaks from the norms and formats established in modernity and points to a different notion of temporality. The rich and immersive audiovisual environment found in her installations requires time to allow its full unfolding for the viewer, but simultaneously offers an intimate and sophisticated experience of time. It could be described by what Karen Barad called “the thick now of the present” in which layers of the distant and not so distant pasts coexist.(Barad uses the phrase “the thick now of the present” in several publications. See for example: Karen Barad, “Transmaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings.” GLQ. A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21 (2-3): p. 388; and Karen Barad, “What Flashes Up: Theological-Political-Scientific Fragments,” in Entangled Worlds: Religion, Science, and New Materialisms, Transdisciplinary Theological Colloquia, edited by Catherine Keller and Mary-Jane Rubenstein (New York: Fordham, 2018), p. 23.) Recognizing that the (Soviet) modernist project has been one of the layers forming a dense and thick present, the artist does not attempt to reject, correct, or redo it in order to aspire to ‘become’ contemporary. Rather, she weaves together the threads of ancient and recent knowledge so as to respond to the time of the now. The most significant result of her exploration is the rediscovery of the “we” that speaks most prominently in 18,000 Worlds. Ismailova not only invests in collective art practice, but also draws on alternative, community-based, vernacular thinking and matrilineally transmitted knowledge, thus acknowledging her own belonging to a larger-than-human whole.