Bogoslav Kalaš: the Ghost in the (Painting-) Machine (Article)

My reaction to the work of Bogoslav Kalaš when I first encountered it in the summer of 2009 at Ljubljana’s Galerija Gregor Podnar was mixed and unusual; I wanted to dislike it, but could not. The show focused on Kalaš’s nudes, dating from 1971 to the present, and, being a skeptic, I had to wonder whether the world really needed–then or now–more paintings of naked women draped over furniture. Yet the sheer strangeness of the artist’s practice was too strong a draw. The orchestrated dissonance of the images, which are as layered conceptually as they are physically, was a treat too irresistible. “Come for the cheap thrills,” the work beckoned to me, “but stay for the compelling conundrums.”

Working out these conundrums proved a remarkably rewarding task. Kalaš’s work from the last thirty-odd years (particularly the nudes, which I found the most compelling) demonstrates a range of subtly changing interests, but also stays true to a set of guiding questions. Kalaš asks what it means to create a truthful image in an age when visual glut is as pervasive as a sense of profound epistemological distrust, and what specifically the insight of a painter, and a classically trained one at that, might be.

Despite the significance of these questions, Kalaš’s contribution remains largely unknown. The Rihard Jakopi? Award, Slovenia’s highest artistic honor, which he received in 2006, drew more attention to his oeuvre, but Kalaš’s work has yet to find its place in a broader art-historical context. Those familiar with Slovene post-war art might note that the year 1968, which saw Kalaš’s first exhibition at Ljubljana’s Moderna Galerija, also saw the first show at that institution of the OHO group, now considered Slovenia’s–and, indeed, former Yugoslavia’s–first example of a sustained, committed neo-avant-garde. This seems like more than a mere coincidence. As different as the two practices are, they produced at the time the country’s most extreme and resonant examples of how art can engage unrelenting modernity. Thus, if only given the kind of critical attention paid in recent years to OHO, Kalaš’s work reveals important answers to the queries of a generation.

Every description of Kalaš’s art begins with the fact that in 1971 he invented a painting machine–a contraption so large and elaborate that it cannot leave the artist’s studio in the town of Domžale, Slovenia. Kalaš feeds the machine images from photographs and uses a technique he calls “aerography” to transfer them onto canvas (Figure 1). The machine airbrushes layer upon dense layer of paint under his vigilant eye as he makes necessary adjustments. A single original painting can take several months to produce. The significance of this fact came to me when, in the process of revising this text, I saw the press release for the exhibition Slow Paintings at the Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen. Though Kalaš’s name was not on the list–unsurprisingly, given his seeming disinterest in self-promotion–his work would have qualified doubly. Not only is his painting “slow” because the length of the process of its creation defies any assumed association of mechanization with speed, but more importantly because it also slows us down as we conceptualize historical time. It is an unexpected punctuation mark laying its trap for anyone breezing through an easy narrative of post-war art.

Every description of Kalaš’s art begins with the fact that in 1971 he invented a painting machine–a contraption so large and elaborate that it cannot leave the artist’s studio in the town of Domžale, Slovenia. Kalaš feeds the machine images from photographs and uses a technique he calls “aerography” to transfer them onto canvas (Figure 1). The machine airbrushes layer upon dense layer of paint under his vigilant eye as he makes necessary adjustments. A single original painting can take several months to produce. The significance of this fact came to me when, in the process of revising this text, I saw the press release for the exhibition Slow Paintings at the Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen. Though Kalaš’s name was not on the list–unsurprisingly, given his seeming disinterest in self-promotion–his work would have qualified doubly. Not only is his painting “slow” because the length of the process of its creation defies any assumed association of mechanization with speed, but more importantly because it also slows us down as we conceptualize historical time. It is an unexpected punctuation mark laying its trap for anyone breezing through an easy narrative of post-war art.

In a single word, Kalaš’s oeuvre could be described as “studied”–most obviously because of the diligence of its devotion to traditional forms of a traditional medium. But studied, also, in being the work of someone who has studied carefully centuries of painting’s intellectual crises, wishing to understand the historical shifts behind the visual effects. If Kalaš is interested in tradition, it is, “not because it is always [found] in the imitation of the external appearance of older painting,” but because, “tradition is the continuation of the spirit of old painting.”(Bogoslav Kalaš, “Prihajam v leta, ko postam mlad, obetaven umetnik,” Likovne Besede, May 1997, 7.) It is precisely because Kalaš pursues the spirit of old painting that his technical innovations affirm, paradoxically, the originality of the artist and the special place of the painter in an oversaturated visual world. In this, Kalaš might be seen as holding true to a broader trend in Eastern Europe, where painting, despite the early appearance and development of alternative media and modes of work, retained its centrality and cultural cache throughout the period when Western artists first affirmed and denied the “death of painting.” Nevertheless, what sets Kalaš apart is that he continues to create images in paint while also addressing the nagging doubts about the status and truthfulness of such images.

In 1959, at the dawn of the era of Pop Art, to which Kalaš’s work has an undeniable allegiance, the British art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway wrote, “One reason for the failure of the humanists to keep their grip on public values (as they did in the nineteenth century through university and Parliament) is their failure to handle technology, which is both transforming our environment and, through its product the mass media, our ideas about the world and about ourselves. …The media, however [are] a treasury of orientation, a manual of one’s occupancy of the twentieth century.” Alloway also suggested that, “To approach [an] exploding field [of the expendable multitude of signs and symbols] with Renaissance-based ideas of the uniqueness of art is crippling.”(Lawrence Alloway, “The Long Front of Culture”, in John Russell and Suzi Gablik, eds., Pop Art Redefined (New York: Praeger, 1969), 41-42.)

This comment sheds some light on the complexities of the method of painting-by-machine created by Kalaš, who was a long-time professor and dean of the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, as well as a self-avowed humanist and heir to the Renaissance. He “handles” technology –by removing the artist’s hand–but also proves that technology has no direct bearing on uniqueness. Rather, it is the choice of how to use it that does. In Kalaš’s work, the complex technology is thus used to foreground its own dependence on the power of personal choice at every step of the way. For this reason, Kalaš is careful to set himself apart from photorealism. If photorealism uses classical painterly means to reproduce with utmost trompe l’oeil the look of a photograph, then Kalaš uses the photograph only as part of an integral process, a basis for the image which the artist does not try to reproduce per se, but rather chooses as a suitable basis for subtle distortion. The painter’s vision refers but is not identical to an image made in the most familiar visual medium of our time.

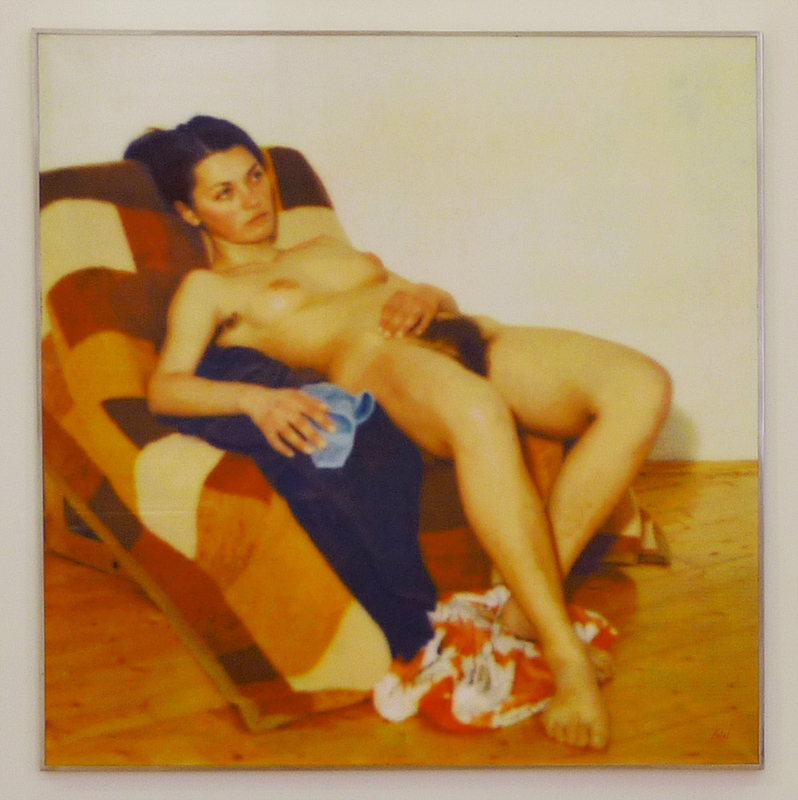

And, indeed, the peculiar blur of a Kalaš painting will not let it be mistaken for a photograph. The consistency of the works’ slight lack of focus combines with the texture and colors of perfectly even acrylic paint to underscore the artifice that defies our expectations of both snapshot photography and painterly craft. Moreover, Kalaš’s tonalities often amplify an eerie sense of light (Figure 2). It becomes almost palpably present in the pictures, further foregrounding the material means of mediating images by hearkening to self-conscious preoccupations with light in both photographic and painterly traditions. The physical properties of the work are so prominent that they leave no choice but to wonder about the process of their production; the visually noticeable removal of the artist’s hand (which would surely only smudge the desired effect were it to be applied directly to the canvas) forces us to search harder for the elusive place of the painter within his work, to wonder how he might be present.

And, indeed, the peculiar blur of a Kalaš painting will not let it be mistaken for a photograph. The consistency of the works’ slight lack of focus combines with the texture and colors of perfectly even acrylic paint to underscore the artifice that defies our expectations of both snapshot photography and painterly craft. Moreover, Kalaš’s tonalities often amplify an eerie sense of light (Figure 2). It becomes almost palpably present in the pictures, further foregrounding the material means of mediating images by hearkening to self-conscious preoccupations with light in both photographic and painterly traditions. The physical properties of the work are so prominent that they leave no choice but to wonder about the process of their production; the visually noticeable removal of the artist’s hand (which would surely only smudge the desired effect were it to be applied directly to the canvas) forces us to search harder for the elusive place of the painter within his work, to wonder how he might be present.

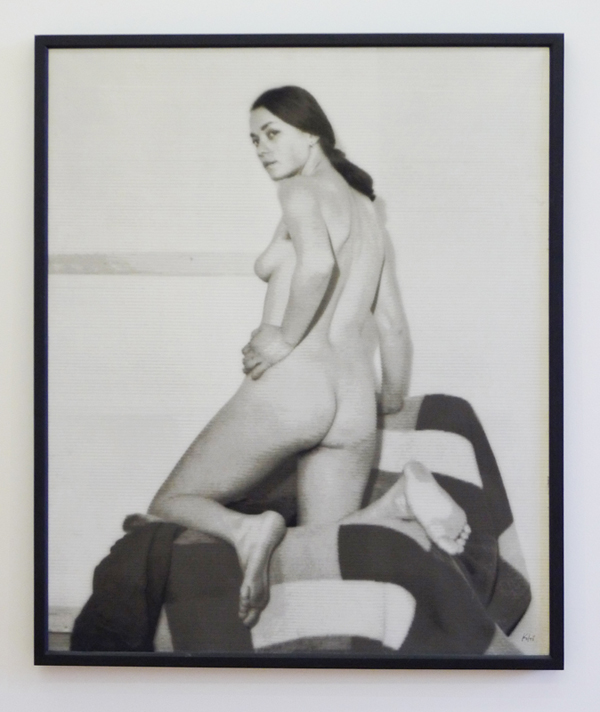

Thus, the machine, which—Kalaš insists—is in essence a tool no different from a regular brush, paradoxically makes us more aware of the artist’s agency. In a truly Duchampian twist, the apparatus exerts a huge amount of energy, electric and otherwise, to point at a classical nude and say, “This too is contemporary art.” And, as if to push the irony further, Kalaš himself muses that “possibly the only conceptual element [in his work] is the choice of classical genres.”(Kalaš, “Prihajam v leta,” 13.) In the case of the nudes, the genre to which he keeps returning is not incidental. Muted but not erased by the softened focus, naked bodies without familiar hard edges become less recognizable and less pornographic the closer you get to them–a perfect metaphor for Kalaš’s exploration of images uncertain of their own status (Figure 3).

Thus, the machine, which—Kalaš insists—is in essence a tool no different from a regular brush, paradoxically makes us more aware of the artist’s agency. In a truly Duchampian twist, the apparatus exerts a huge amount of energy, electric and otherwise, to point at a classical nude and say, “This too is contemporary art.” And, as if to push the irony further, Kalaš himself muses that “possibly the only conceptual element [in his work] is the choice of classical genres.”(Kalaš, “Prihajam v leta,” 13.) In the case of the nudes, the genre to which he keeps returning is not incidental. Muted but not erased by the softened focus, naked bodies without familiar hard edges become less recognizable and less pornographic the closer you get to them–a perfect metaphor for Kalaš’s exploration of images uncertain of their own status (Figure 3).

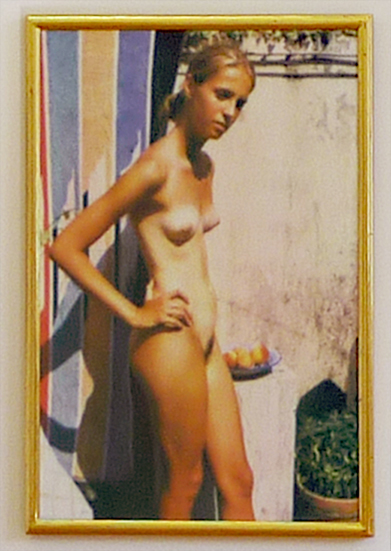

Moreover, while giving his nod to the tradition of using the female body as a site for metaphorical projections, Kalaš excels at the slightly awkward nude. Marlene Dumas, an outstanding figure painter who bases her work on found images, says of her models, “There ain’t no virgins here.” Her equation of having one’s technologically transformed image displayed to the public eye with losing one’s virginity is revealing. Representation often amounts to a great disruption of privacy, and Kalaš’s work does not lose sight of this fact. The apparent casualness of the naked women he depicts never quite erases the physical strain of posing for the source photograph (which Kalaš takes) or the knowing returned gaze–familiar results of a body’s self-conscious encounter with the camera (Figures 4 & 5). At the same time, the eye’s inability to focus heightens the viewer’s tension between beholding someone baring it all and sensing that it is the luxury of elusiveness thatmakes her most present.

Moreover, while giving his nod to the tradition of using the female body as a site for metaphorical projections, Kalaš excels at the slightly awkward nude. Marlene Dumas, an outstanding figure painter who bases her work on found images, says of her models, “There ain’t no virgins here.” Her equation of having one’s technologically transformed image displayed to the public eye with losing one’s virginity is revealing. Representation often amounts to a great disruption of privacy, and Kalaš’s work does not lose sight of this fact. The apparent casualness of the naked women he depicts never quite erases the physical strain of posing for the source photograph (which Kalaš takes) or the knowing returned gaze–familiar results of a body’s self-conscious encounter with the camera (Figures 4 & 5). At the same time, the eye’s inability to focus heightens the viewer’s tension between beholding someone baring it all and sensing that it is the luxury of elusiveness thatmakes her most present.

Even though his work inadvertently exposes some of the discursive edges–Derridian parerga–that mark images as art and people as artists, Kalaš is not a Conceptualist. His work assumes the centrality of the image, and what’s more, Kalaš wants the image to possess the elusive quality of truthfulness and trustworthiness. He repeats emphatically that he invented his machine because he was convinced that no available traditional means were suitable for presenting the feel of the visible world of his time. “I work in this manner because, I’d like to stress this again, the traditional methods did not make it possible for me to identify with the age in which I live.”(Ibid., 6, 11; Bogoslav Kalaš, “Ko pridem v Benetke, tr?im ob Turnerja in Moneta!” Likovna Vzgoja, December 2006-January 2007, 6.)

Even though his work inadvertently exposes some of the discursive edges–Derridian parerga–that mark images as art and people as artists, Kalaš is not a Conceptualist. His work assumes the centrality of the image, and what’s more, Kalaš wants the image to possess the elusive quality of truthfulness and trustworthiness. He repeats emphatically that he invented his machine because he was convinced that no available traditional means were suitable for presenting the feel of the visible world of his time. “I work in this manner because, I’d like to stress this again, the traditional methods did not make it possible for me to identify with the age in which I live.”(Ibid., 6, 11; Bogoslav Kalaš, “Ko pridem v Benetke, tr?im ob Turnerja in Moneta!” Likovna Vzgoja, December 2006-January 2007, 6.)

Which brings us to the issue of realism. While Kalaš is not a photo-realist he should, justifiably, be considered in the context of the global early 1970s moment that went under various names, but was, perhaps, most adequately summed up as “Super realism.”(The term was a title of the anthology edited by Gregory Battcock in 1975.) In a 1972 review of the exhibition Sharp-Focus Realism, the critic Harold Rosenberg wrote of this art that it “represents a renewed relation not between art and reality, or nature, but between art and the artifacts of modern industry, including the mass media. The new paintings and sculptures converge with Pop in that both modes, while seeming to base art on life, actually convert it into variations on existing techniques of visual communication.”(Harold Rosenberg, “Reality Again” in Gregory Battcock, ed., Super realism: a critical anthology (New York: Dutton, 1975), 136.) Though Rosenberg’s words still strike one as prescient today, looking thirty years later at Kalaš’s continued engagement with these themes, we can say that the relationship between art and the impact of the artifacts of modern industry is the reality which the artist strives to address truthfully.

The genius (in the sense of “spirit”–or ghost) of such work lies in a surprising realization. Namely, that in an ostensibly post-medium condition, mediation by and through paint still makes a big difference to what we seek and find in a picture. The artist, instead of losing himself in the age of mechanical reproduction, here reclaims his role as a keeper of allegories and as a history painter. But the “history paintings” he produces have little to do with biblical or mythological subjects. Rather, the material evidence he preserves is that of a visual world coming to find its truths in the limitations of the devices that produce it, as well as of the shifting emphases of meaning inherent in the act of translation from one medium to another.

The genius (in the sense of “spirit”–or ghost) of such work lies in a surprising realization. Namely, that in an ostensibly post-medium condition, mediation by and through paint still makes a big difference to what we seek and find in a picture. The artist, instead of losing himself in the age of mechanical reproduction, here reclaims his role as a keeper of allegories and as a history painter. But the “history paintings” he produces have little to do with biblical or mythological subjects. Rather, the material evidence he preserves is that of a visual world coming to find its truths in the limitations of the devices that produce it, as well as of the shifting emphases of meaning inherent in the act of translation from one medium to another.

Nor isKalaš alone in these preoccupations. His works share much of their logic with the celebrated “photo paintings” of Gerhard Richter, of which the art historian Benjamin Buchloh writes, “[when] the indices of represented reality and the indices of the reality of the representation are interwoven. …What appears blurred is, in fact, the very precision of the self-reflexive pictorial practice.”(Benjamin Buchloh, “Readymade, Photography, and Painting in the Painting of Gerhard Richter,” in Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2003), 388.) (Figure 6). In Richter’s case, the translation of the blur, which is much more pronounced than in Kalaš’s work, is put in the service of traumatic social memory, stylistic eclecticism, and a critique of the devaluing effects of mass media on the images it produces. Kalaš’s work is more reserved. The intimacy of the subject matter he pursues in the nudes does not lend itself to pathos and results in a more private involvement of the model, artist, and viewer with the world, where new images face almost immediate disposability and new devices an impending obsolescence. On such a human scale, however, the “truth to life” in light, color, and texture captures human form alongside the look and feel of technological exigencies; in threatening to slip away it becomes bearable, acceptable–or even beautiful (Figure 7). As someone dedicated to certain old-fashioned notions, Kalaš should be pleased by this.

Nor isKalaš alone in these preoccupations. His works share much of their logic with the celebrated “photo paintings” of Gerhard Richter, of which the art historian Benjamin Buchloh writes, “[when] the indices of represented reality and the indices of the reality of the representation are interwoven. …What appears blurred is, in fact, the very precision of the self-reflexive pictorial practice.”(Benjamin Buchloh, “Readymade, Photography, and Painting in the Painting of Gerhard Richter,” in Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2003), 388.) (Figure 6). In Richter’s case, the translation of the blur, which is much more pronounced than in Kalaš’s work, is put in the service of traumatic social memory, stylistic eclecticism, and a critique of the devaluing effects of mass media on the images it produces. Kalaš’s work is more reserved. The intimacy of the subject matter he pursues in the nudes does not lend itself to pathos and results in a more private involvement of the model, artist, and viewer with the world, where new images face almost immediate disposability and new devices an impending obsolescence. On such a human scale, however, the “truth to life” in light, color, and texture captures human form alongside the look and feel of technological exigencies; in threatening to slip away it becomes bearable, acceptable–or even beautiful (Figure 7). As someone dedicated to certain old-fashioned notions, Kalaš should be pleased by this.