Art Periodicals and Contemporary Art Worlds, Part 2: Critical Publicity in a Global Context

Editors note: The following essay by Gwen Allen is Part 2 of a two-part essay devoted to critical art periodicals past and present. Part 1 appears in ARTMargins Print (#5.3, 2016), our Special Issue Art Periodicals Today, Historically Considered that extends across both ARTMargins platforms. Future articles will unfold in the coming weeks and include: “Have a Look: A Short History of Art Periodicals in Yugoslavia” by Darko Šimi?i? and “Art Periodicals in Eastern Europe: A Critical Survey.”

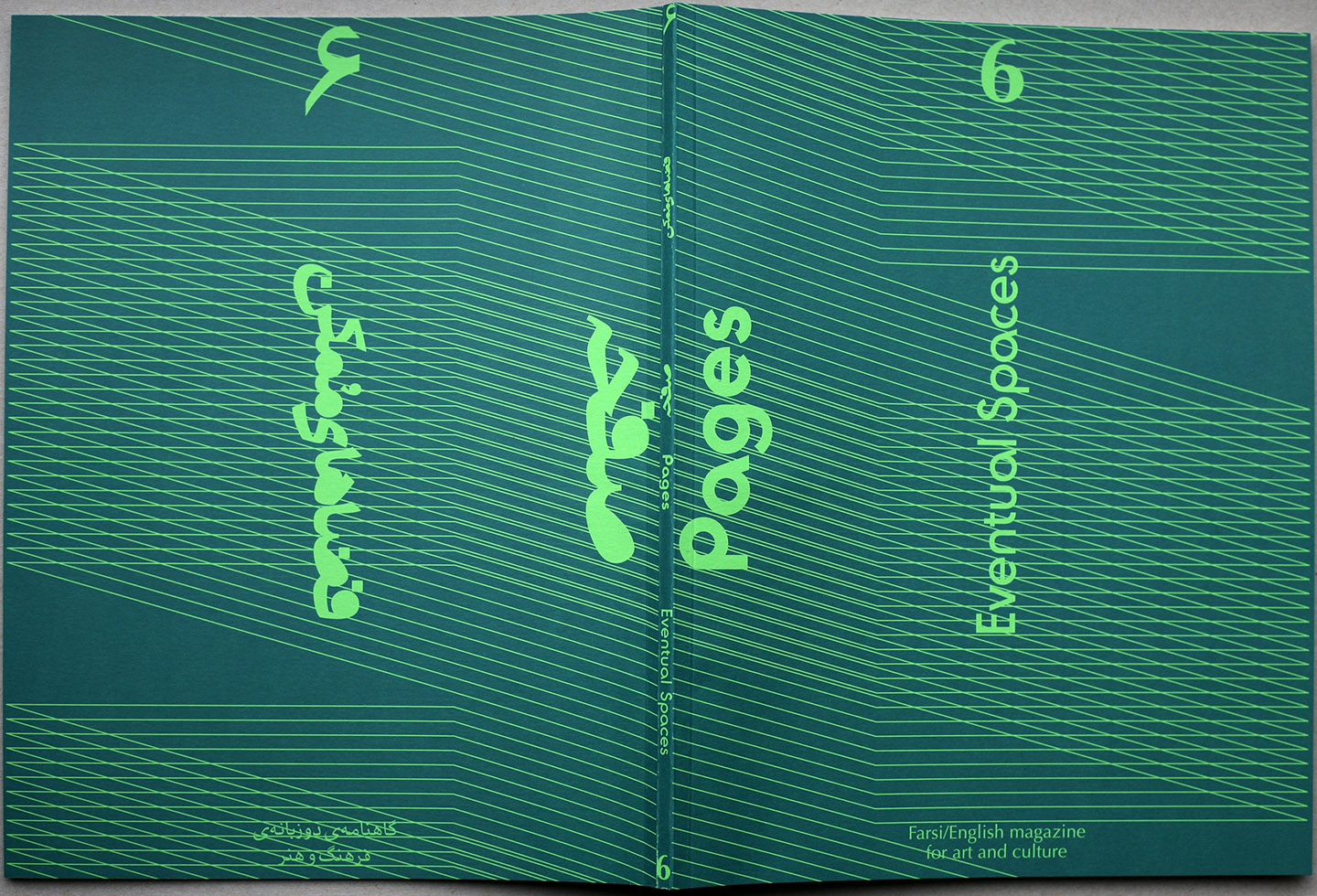

In “Art Periodicals and Contemporary Art Worlds, Part 1: An Historical Exploration” (published issue #5.3, 2016 of ARTMargins Print), I examine the history of art periodicals, and explore their formative role in the North American art world of the 1960s and 1970s, as sites of promotional publicity and spectacle, as well as various forms of critical exchange and counterpublicity. That history provides a kind of genealogy for understanding the role of art periodicals in the contemporary art world—a contested term that, like globalization itself, signals both the geographical expansion of formerly Western, modern definitions and institutions of art and the homogenization and the neoliberal exploitation of artistic production around the globe.(For two important accounts of the contemporary art world see Pamela M. Lee, Forgetting the Art World (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2013); and Octavian Esanu, “What Was Contemporary Art?” ArtMargins 1:1 (2011): 5-28.) Indeed, today, a handful of (mainly) English-language art magazines and online platforms dominate the circulation of information in ways that tend to uphold the art world’s geopolitical hierarchies, and facilitate art’s instrumentalization within neoliberal systems of economic, social, and political power.(For a more in depth discussion of this, see my “Art Periodicals and Contemporary Art Worlds, Part 1: An Historical Exploration” ArtMargins, 5:3 (2016). Also for an important account of how digital technologies have transformed the circulation of information and images in the contemporary art world see David Joselit, After Art (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2013).) Yet in recent years a number of publications have emerged to question the hegemony of Western institutions, to represent local and regional artistic communities and interests, and to foster transnational dialogue and exchange. Examples include: the bilingual magazine Pages, conceived as “a platform for exchanging thoughts and artistic projects reflecting on the sociopolitical currents in Iran and elsewhere;”(Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiab, “Introduction,” Pages no. 1 (February 2004), 2.) the Capetown-based Chimurenga, which “seeks to write Africa in the present and into the world at large;”(“The Chimurenga Chronic: A future-forward, pan African newspaper” (unsigned publicity brochure) accessedAugust 9, 2015, http://chimurengachronic.co.za/) and Chto Delat?, launched by the St. Petersburg-based artistic collective of the same name as a site of political and artistic engagement within Putinist Russia. While these publications vary widely in their formats, editorial goals, and readership, they share a desire to intervene into dominant structures of information and distribution and/or to create new, alternative ones. In what follows I will discuss several such periodicals, many of which are published outside of North America and the former Western Europe, and examine how they function as sites of critical publicity within the contemporary art world, even as they challenge its borders and question its authority.

Some open onto worlds vastly different than the art world broadcast in the pages of Artforum or Frieze. Consider, for example, Gahnama-E-Hunar, the first, and to date only, independently published art magazine in Afghanistan. Gahnama-E-Hunar was founded in 2000 by the artist Rawraw Omarzad to serve the needs of Afghani artists in the face of civil war, displacement, and repression under the Taliban, which had forbidden art. “In such an atmosphere,” Omarzad recalled, “there was a danger that a new generation of young people and young artists would grow up without knowledge of art.”(Rawraw Omarzad, “Gahnama-E-Hunar,” in Octavian Esanu, ed., Critical Machines: Exhibition and Conference. Exhibition catalog. (Beirut: American University Beirut, 2014), 114.) Risking reprisal from the Taliban (which had also outlawed magazines, after all), Omarzad produced the first issue of Gahnama-E-Hunar while he was living in Pakistan as a refugee. According to him, one of the primary original purposes of the magazine was to let the dispersed community of Afghani artists know that they were still alive.(Rawraw Omarzad, “Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today” (Conference), American University of Beirut, March 7-8, 2014.) Published in Dari and Pashtu with short abstracts in English, it featured traditional forms of Afghan painting, sculpture, and calligraphy as well as visual art, music, and films by Afghani artists working and exhibiting abroad. Gahnama-E-Hunar also reported on important historical and contemporary figures both inside and outside of the country, from Ghulam Mohammad Maimanagi to Edward Munch to Siddiq Barmak. The magazine chronicled not only the devastation of cultural life, but its persistence and gradual restoration, witnessed for example by the reopening of the National Gallery of Afghanistan in 2002. Gahnama-E-Hunar is an especially stark example not only of how vital magazines can be to artistic communities but also how differently they function across the globe.

In their attempt to forge alternative models of publicity, today’s critical publications echo—sometimes quite deliberately—the DIY ethos and innovative formats of little magazines and artists’ magazines of the 1960s and 1970s in the West, such as October, Avalanche, The Fox, FILE, Heresies, Lip and Black Phoenix, which functioned as alternatives to the mainstream art world and press.(See my Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011).) Such publications served as vital sites of critical publicity and counterpublicity within the Western art worlds of their time by supporting experimental art forms outside the commercial gallery system, promoting artists’ moral and legal rights, and fostering queer, feminist and postcolonialist art practices. Like these predecessors, the publications I discuss here tend to embrace their noncommercial status, whether it is by choice or necessity, and to develop innovative, participatory formats and frameworks that stress self-determination andagency. Against the predictability and accelerated pace of mainstream media they are more likely to be sporadically published and precariously funded—a circumstance that may heighten their contingency and connection to a specific time and place, even as it precludes longevity (indeed some are no longer extant.) Yet, while they may revisit past publishing strategies, a number of critical art magazines today are also transforming them and inventing new models of publishing.

This essay is by no means a comprehensive survey, more like a selective, and maybe even somewhat arbitrary, sampling of critical art periodicals globally. I also want to acknowledge that I have learned about many of these publications vis-à-vis their reception within Western institutions, including the 2007 Documenta Magazines project, and the 2014 Critical Machines conference at American University Beirut (and more specifically from the documentation and publicity surrounding these events since I did not attend either in person).(See the edited transcripts of the Critical Machines conference in ArtMargins, 5:3 (2016).) However, this irony goes to the heart of the politics surrounding distribution, visibility, access, and audience that so many of these publications grapple with as they mediate between local or marginalized art worlds and a larger global arena—politics that this essay reflects upon but also necessarily participates in. While I want to highlight the progressive potential of periodicals as sites of self-representation, community, and critical dialogue for local and global publics, I also want to recognize the uneven power relationships that govern the exchange and distribution of information in today’s art world.

Such disparities were foregrounded by the 2007 Documenta 12 Magazines project, which sought to showcase the critical potential of art magazines globally by inviting over 90 periodicals from over 50 countries to generate essays, features, and artists’ projects that considered the exhibition’s themes from local perspectives. The participating magazines were then exhibited at the exhibition proper and via an online archive, selections from which were anthologized in three issues of a printed publication entitled Documenta Magazine. As Georg Schöllhammer, who organized the project, explained, “Our intention was to work in truly decentralized fashion and thus to enable forms different from the canonized ones for the interpretation of the history of contemporary art.”(Georg Schöllhammer, interview by Elena Zanichelli, Documenta 12 website, accessed August 9, 2015, http://www.documenta12.de/index.php?id=1389&L=1.) Accordingly, Artforum, October, and Frieze were omitted in favor of lesser-known or geographically marginalized publications that might counter the exhibition’s homogenizing tendencies and provide a “kaleidoscopic view of specific moments, configurations, and positions.”(Georg Schöllhammer, editorial, Documenta Magazines nos. 1–3, 2007 Reader (Cologne: Taschen, 2007), n.p.)

While Documenta 12 Magazines sought to promote these magazines as local sites of knowledge production and reception, the project was also criticized for its attempt to capitalize on and co-opt this knowledge. Writing in Radical Philosophy (one of the magazines that participated in the project), Peter Osborne observed that Documenta Magazines “perform[ed] an intellectual and political legitimation function for Documenta [which] acquired intellectual product to order…free of charge, in a way that legitimated its ‘cutting edge’ pretensions (multinational, de-territorialized, politically progressive).”(Peter Osborne, “Documenta 12 Magazines Project Debacle,” Radical Philosophy 146 (November/December 2007): 39.) These dynamicsinvolving institutional power and the alleged exploitation of intellectual and artistic labor were exacerbated by the global ambitions and scope of the project, as was thrown into relief at a meeting of editors, writers, and artists from East and Southeast Asia, in which they voiced their frustrations with the project, which was accused of “poaching, this big monster of the West devouring/scouring for content elsewhere,” while neglecting the local conditions under which the magazines were produced.(Stated at an initial Documenta12 Magazines meeting hosted in Singapore, quoted in Kean Wong, “Magazines Mania at Documenta 12,” Nafas Art Magazine (September 2007), accessed August 9, 2015, http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2007/doc12_magazines_mania.) They discussed the specific challenges facing magazines in Asia, including struggles to survive economically, and the return of state-sponsored censorship in several of their countries, as well as clever tactics developed to evade it. As one editor pointed out, “The curators [of Documenta] never really dealt with the reality of art publications in Asia, where we’re almost exclusively independent, alternative and self-funded.”(Kathy Rowland, quoted in Kean Wong, “Magazines Mania at Documenta 12.”) And yet these very conditions also made it virtually impossible for these magazines to turn down the invitation to participate. “There’s so little information trickling from this side of the planet to Europe, that it seemed irresponsible to pass up the opportunity,” as one editor explained.(Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez, quoted in Kean Wong, “Magazines Mania at Documenta 12.”)

Such remarks prompt reflection on the differences that structure the conditions and meaning of publishing around the globe and suggest that efforts to assimilate the contemporary art world’s many different publics into a single arena may be misguided. For their part, the Magazines project’s organizers were optimistic about its prospect as a kind of global public sphere within which diverse perspectives could be articulated and exchanged. Schöllhammer imagined the magazines functioning as “educational and transmission stations between those who make art and those who think about it, between small very specific publics and other larger public spheres” and described the project as “a space for an exchange of opinions, for debate, controversy and translation.”(Georg Schöllhammer, editorial, Documenta Magazines nos. 1–3, 2007 Reader, n.p.) However well intended, such rhetoric calls to mind post-national, cosmopolitan approaches to the public sphere, which often, as critics such as Chantal Mouffe have argued, mask the underlying inequalities that structure any global arena, and serve as a thinly veiled justification for extending neoliberal democracy to the entire globe.(Chantal Mouffe describes the problems of cosmopolitan approaches to the public sphere, writing “If such a project was ever realized, it could only signify the world hegemony of a dominant power that would have been able to impose its conception of the world on the entire planet and which, identifying its interests with those of humanity, would treat any disagreement as an illegitimate challenge to its ‘rational’ leadership.” On the Political (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 107.) Against this model of a single, universal global public, Mouffe has called for a multipolar, agonistic public sphere that precludes the very possibility of rational consensus in favor of ongoing and irreconcilable differences, where antagonisms are legitimately admitted and fought over rather than repressed or resolved: a “battleground where different hegemonic projects are confronted, without any possibility of final reconciliation.”(Chantal Mouffe, “Art and Democracy: Art as an Agonistic Intervention in Public Space,” in Open 14 (2008), 10.) Such a model, she writes, “requires coming to terms with the lack of a final ground and the undecidability which pervades every order….Things could always be otherwise and therefore every order is predicated on the exclusion of other possibilities.”(Ibid., 8.)

Despite the potential for an indeterminate, agonistic sphere which might acknowledge and reflect the irreducibly complex and heterogeneous reality of artistic production globally today, the contemporary art world most frequently falls back on the myths of universalism that underlie cosmopolitan, postnational approaches. Indeed, to even conceive of the art world as a single entity belies a covert universalism. While Documenta 12 Magazines performed a valuable service by increasing the visibility of participating publications and highlighting the importance of periodicals more generally, its attempt to synthesize the contemporary art world’s proliferating publics and perspectives into a single ensemble, underwritten by the institutional space and authority of Documenta, implicitly perpetuated such myths of universalism. Emblematic of these shortcomings were the Documenta Magazines anthologies, which in many ways ended up reinforcing the hierarchies the project had set out to undo. These three generic volumes, conceived as a kind of “best of” compilation, were criticized for having “cherry picked” celebrities, and homogenizing the various magazines—quite literally effacing their differences within a uniform design.(David Cunningham, “The Death of a Project,” 217; For a critical discussion of Documenta 12 Magazines and the Documenta Magazine anthology see Claire Bishop, “Writer’s Bloc,” Artforum, September 2007, 415.) Stripped of their materiality and temporality, their conditions of circulation and distribution, the participating magazines were deprived of those very attributes, qualities, and conditions through which they mediate communication.

It is precisely those attributes, qualities, and conditions with which I am concerned here. Publications produce meaning not only through their content but also through their format and means of distribution, editorial structure, mode of address, and conditions of production and circulation. As I will discuss in more detail below, one of the ways publications function critically in today’s art world is by foregrounding their materiality and specificity as structures of information and distribution, whether printed or online. In this sense, they suggest site-specific approaches to publishing, which self-reflexively consider how communication is modulated by context, location, and audience — even as they undermine fixed, essentialist notions of such entities.(The artist Andrea Frazer has used the term site-specific in reference to criticism: “Thinking site-specifically means writing for an audience or readership in an active way. It means not misrecognizing your readership as the other of your discourse but as the actual people who are probably going to be picking up the magazine and looking through its pages.” Andrea Frazer, “Round Table: The Present Conditions of Art Criticism,” 223.) Against the neoliberalist rhetoric of “multiplicity” and pluralism which acknowledges difference only to tame and exploit it, I want to explore how publications might hold out the possibility for an agonistic art world — one that acknowledges contradictions and antagonisms rather than trying to resolve or repress them, and that encourages different points of view without subscribing to or imposing a single universal criterion for inclusiveness and legitimacy. Instead of seeking representation within a single presiding art world, the publications I will discuss below attempt to mediate between the many different worlds that constitute the reality of art today, and enact the dilemmas of inhabiting multiple art worlds at once.

While they often represent marginalized artistic communities and identities, these publications simultaneously challenge the reductive terms through which these identities are so often exploited and marketed within the global art world. For example, Pages was founded in 2004 by artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, as a multifaceted platform, including a print magazine as well as various research activities and projects, architectural proposals, video documentation and installation works, with a particular focus on the context of contemporary Iran. One of the initial editorial imperatives was to overcome the simplistic, stereotyped terms through which Iranian art is so often represented in the mainstream institutions of the art world, though Pages has now evolved into a platform for exploring the relationship between contemporary artistic practice, culture, history and geopolitics more broadly. The editors describe the activities and projects featured in Pages as “ongoing processes of research, which inevitably tend to undermine predefined and geographically bound notions of subjectivity and locality.”(Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, “About Pages,” Pages, accessed August 9, 2015, http://www.pagesmagazine.net/index.php?nocheck.) To this end, they position the magazine not in relationship to a single, discrete location, but to multiple places, audiences, and languages. Produced in both Tehran and Rotterdam, Pages is published bilingually in Farsi and English, and distributed online and in print, in bookstores in Europe and more unofficially in Iran, where the editors give it to people they know or meet, and it is then passed from hand to hand. Portions of the print magazine are also archived online (http://www.pagesmagazine.net/).(Pages is in the process of relaunching its website with complete access to full issues, past and future. The URL will not change: http://www.pagesmagazine.net/.) According to its editors, Pages seizes upon this “doubleness” as “a reflection on how contemporary art is experienced and practiced outside of the so called capitals of the ‘art world.’”(Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, email to the author, September 20, 2015.) Instead of trying to resolve or seamlessly synthesize the multiple contexts within which the magazine exists, Pages underscores the complexities of such multiplicity, which is embodied in the very layout of its printed version, in which Farsi and English texts are intertwined. Its editors explain, “We didn’t want to divide the magazine into two sections but rather, to stay faithful to the displaced nature of translation, we decided to let the two languages mix, or pass through one another.”(Ibid.)

While they often represent marginalized artistic communities and identities, these publications simultaneously challenge the reductive terms through which these identities are so often exploited and marketed within the global art world. For example, Pages was founded in 2004 by artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, as a multifaceted platform, including a print magazine as well as various research activities and projects, architectural proposals, video documentation and installation works, with a particular focus on the context of contemporary Iran. One of the initial editorial imperatives was to overcome the simplistic, stereotyped terms through which Iranian art is so often represented in the mainstream institutions of the art world, though Pages has now evolved into a platform for exploring the relationship between contemporary artistic practice, culture, history and geopolitics more broadly. The editors describe the activities and projects featured in Pages as “ongoing processes of research, which inevitably tend to undermine predefined and geographically bound notions of subjectivity and locality.”(Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, “About Pages,” Pages, accessed August 9, 2015, http://www.pagesmagazine.net/index.php?nocheck.) To this end, they position the magazine not in relationship to a single, discrete location, but to multiple places, audiences, and languages. Produced in both Tehran and Rotterdam, Pages is published bilingually in Farsi and English, and distributed online and in print, in bookstores in Europe and more unofficially in Iran, where the editors give it to people they know or meet, and it is then passed from hand to hand. Portions of the print magazine are also archived online (http://www.pagesmagazine.net/).(Pages is in the process of relaunching its website with complete access to full issues, past and future. The URL will not change: http://www.pagesmagazine.net/.) According to its editors, Pages seizes upon this “doubleness” as “a reflection on how contemporary art is experienced and practiced outside of the so called capitals of the ‘art world.’”(Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, email to the author, September 20, 2015.) Instead of trying to resolve or seamlessly synthesize the multiple contexts within which the magazine exists, Pages underscores the complexities of such multiplicity, which is embodied in the very layout of its printed version, in which Farsi and English texts are intertwined. Its editors explain, “We didn’t want to divide the magazine into two sections but rather, to stay faithful to the displaced nature of translation, we decided to let the two languages mix, or pass through one another.”(Ibid.)

As the example of Pages suggests, questions of language and translation are key to how publications both define and complicate their audiences and contexts in a global arena. The ubiquity of English in the contemporary art world, which is central to its maintenance of Western hegemony, poses a dilemma for publications that wish to both foster regional identity and participate in transnational dialogue.(For a discussion of the politics of this, see Hito Steyerl, “International Disco Latin,” E-Flux Journal 45 (May 2013).) While many, like Pages, are bilingual, or even trilingual, others choose to publish exclusively in a vernacular language, a decision that may reflect more accurately the goals and function of the publication, even as it limits readership. Such is the case with the online journal Arteria (http://www.arteria.am/), established, according to founding editor Vardan Azatyan, to “fill the gap of critical reflection upon cultural life in Armenia” under “an almost hopeless atmosphere of the country’s neo-colonialization.”(Vardan Azatyan, “Arteria” in Octavian Esanu, ed., Critical Machines Exhibition and Conference. Exhibition catalog. (Beirut: American University Beirut, 2014), 82.) The fact that Arteria is published solely in Armenian is key to the publication’s editorial goals and its relationship to readers, reinforcing the journal’s vital role in its own country and helping to express—and ensure—its allegiance to this primary audience.

Conversely, publications may renounce a local language in favor of English in order to increase visibility and international and/or regional readership. For example, the Malaysian art magazine SentAp! chose to publish in English rather than Bahasa Malaysia in order to overcome parochialism and foster international as well as regional dialogue with neighbouring art scenes in The Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand. According to its editor, Nur Hanim Mohamed Khairuddin, “Our aim is to try to introduce and elevate Malaysian art to the international stage thus it is necessary to use English.”(Nur Hanim Mohamed Khairuddin, quoted in Gina Fairley “SentAp! – Art without Prejudice,” Nafas Art Magazine (September 2006), accessed August 9, 2015, http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2006/sentap.) Yet this decision led to strong criticism by the local art community and established art institutions within Malaysia.(Gina Fairley “SentAp! – Art without Prejudice,” Nafas Art Magazine (September 2006), accessed August 9, 2015, http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2006/sentap.) As such examples make clear, far from being a given, considerations of language are fraught and deeply political, depending not only on the geographical location of a publication’s production, but on its readership, distribution, and editorial goals. Rather than trying to overcome such tensions, these periodicals reflect upon the complexities of a multilingual art world, denaturalizing the prevalence of English, while at the same time stressing the ambiguities and inadequacies of translation.

Digital and online media have obviously transformed and expanded the possibilities for distribution in a global context, and indeed, the majority of the publications discussed here have an online version or are published solely online. While online distribution is mandated in part by pragmatic considerations of cost and access, it is also informed by critical and tactical approaches to digital media, which reflect specific editorial goals and geopolitical conditions. Indeed, even as they mine the progressive potential of digital communication, these magazines challenge the neoliberal hype surrounding the Internet and its claims to universal accessibility, by stressing the different conditions in which the medium is used and accessed around the world. For example, the online publication ArtTerritories (http://www.artterritories.net/) was founded by the Zurich-based artist Ursula Biemann and the Ramallah-based artist Shuruq Harb in response to the mobility restrictions that impede contact and communication between Palestinian artists both within the region and outside it. According to Harb, ArtTerritories was intended to overcome the isolation and fragmentation of the Palestinian artistic community on a local, regional, and international level by providing “a much needed space for artists’ writing empowering the artist voice, and instigating opportunities for exchange and dialogue.”(Shuruq A. M. Harb, in Ursula Biemann and Shuruq A. M. Harb, “ArtTerritories: Online Publishing in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in xurban_collective, eds., The Sea-Image: Visual Manifestations of Port Cities and Global Waters (New York: Newgray: 2011), 104.) As she explains, “The drive to be online was quite simple—a way of reaching out to people even though we couldn’t be physically present.”(Shuruq A. M. Harb, “Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today” (Conference), American University of Beirut, March 7-8, 2014.)

Yet, rather than touting the Internet’s utopian claims to universal access and democracy, ArtTerritories witnesses how the medium has been inflected by the specific conditions of contemporary Palestine, where it has served as a crucial political and educational tool in the face of occupation and containment.(Ursula Biemann and Shuruq A. M. Harb, “ArtTerritories: Online Publishing in the Eastern Mediterranean.”) According to Harb, “The actual form of ArtTerritories was developed in response to these conditions” and “was tailored to the needs and conditions of the art scene rather than reproducing a traditional style magazine.”(Ibid., 106; 103.) The publication is structured not around sequential issues or articles, but based on a distinctive format called “Trails,” a series of linked interview chains, in which an artist/writer interviews another artist/writer of their choice and so on—forming a “discursive waterhole” that evolves organically out of personal networks between artists.(Ibid., 107.) The “Trails” destabilize the hierarchy between interviewer and interviewee, and accentuate individual differences in conversational style and tone, thus precluding a single authoritative or essentialized representation of the Palestinian, Arab, or Middle Eastern art community. Contributors have included the Birzeit-based architectural scholar Yazid Anani, the Los Angeles-based Iraqi and American artist Rheim Alkadhi, the Egypitan graffiti artist Ganzeer, and the American scholar Thomas Keenan—a community unified not by location, ethnicity, or nationality so much as by shared intellectual and artistic interests. While ArtTerritories embraces the possibilities of online communication, it also questions its dominant protocols and conventions. Because the Trails interviews takes place slowly over months, they have “time embedded” in them, Harb observes, and thus resist the instantaneity and relentless information turnover of the Internet.(Shuruq A. M. Harb, “Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today” (Conference), American University of Beirut, March 7-8, 2014.) Indeed, in contrast to typical art magazine websites, which bombard readers with an incessant tickertape of images and information, the spare, deliberate interface of ArtTerritories, consisting of simple dropdown menus from which the archived interviews can be easily followed, feels like a respite—a place to read and think at one’s own pace, and to return to again, and again.

Another publication that interrogates the fate of the public sphere in a digital age is the Sarai Reader (http://sarai.net/category/publications/sarai-reader/), founded by the Delhi-based organization Sarai (comprised of a collective of artists and scholars including the Raqs Media Collective and the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies). The Sarai Reader explores alternative and counterhegemonic definitions of the “public domain,” particularly in the context of contemporary India, where notions of the public sphere have historically been fraught with forms of social control imposed by colonial power.(Editors, “dak@sarai.net: Dicussion the Public Domain,” Sarai Reader 01 (2001): 1-11.) The name Sarai refers to the caravan stations that were once widespread in Delhi—makeshift public spaces for travelers to rest, converse and socialize—a function the organization and publication seek to reclaim by providing a welcoming yet provisional space for discourse and intellectual collaboration. In both its content and distribution form (a series of PDF’s freely available online for download), the Sarai Reader investigates the potential of the digital commons as a site of radical media practice. The Sarai Reader’s status as a provisional, open-ended form of discourse is suggested by the diversity of its contents, which encompass various voices, rhetorical styles, disciplines, and modes of address. The first issue begins with an extended email correspondence between several of the editors, preserving both the visual conventions of email and its informal, spontaneous, “thinking aloud” character. It then presents a “patchwork” of heterogeneous voices and genres, from manifestos to scholarly articles to activist how-to guides about open source and free software, which revolve largely around how to liberate the media from corporate interests and state control.(Ibid.) Like a number of other publications discussed here, the Sarai Reader resists fixed, a priori definitions of both the publication and the public alike. It defines the public domain as a “republic without territory…that comes into being whenever people gather and begin to communicate, using whatever means that they have at hand,” and comparing the Reader to “a navigation log of actual voyages and a map for possible journeys into a real and imagined territory.”(Editorial Statement, Sarai Reader 01 (2001), accessed August 9, 2015, http://sarai.net/sarai-reader-01-public-domain/)

In yet a different context, the Capetown-based Chimurenga (http://www.chimurenga.co.za/) explores the complex, reciprocal relationship between online and printed communication, as well their overlap with live events, spaces, and actions. Founded by Ntone Edjabe in 2002, Chimurenga bills itself as a “pan African publication of writing, art and politics,” produced in Capetown but distributed globally.(“About Us,” Chimurenga website, accessed September 1, 2016, http://www.chimurenga.co.za/about-us.) The print magazine has grown to encompass a number of different editorial and curatorial activities that traverse digital, printed, and “real” space, including themed performances called Chimurenga Sessions; an online music radio station and live studio known as the Pan African Space Station (PASS); and the Chimurenga Library, an ongoing project that interrogates the public and informational space of the library, supplementing it with a compendium of historical and current African periodicals. Discussing the relationship between online and printed distribution, Edjabe has stated, “it was important for us to exist in print, in order to make the intervention we needed to make in the body of written material on and/or from Africas. But I also feel the debate between online and print is an old debate. I don’t think one excludes the other, and that’s the approach we chose. To have a presence in both spheres.”(Ntone Edjabe, “Chimurenga: who no know go know.” Interviewed by Dídac P. Lagarriga, An interview with Ntone Edjabe. Oozebap, accessed August 10, 2016, http://www.oozebap.org/text/chimurenga.htm)

In yet a different context, the Capetown-based Chimurenga (http://www.chimurenga.co.za/) explores the complex, reciprocal relationship between online and printed communication, as well their overlap with live events, spaces, and actions. Founded by Ntone Edjabe in 2002, Chimurenga bills itself as a “pan African publication of writing, art and politics,” produced in Capetown but distributed globally.(“About Us,” Chimurenga website, accessed September 1, 2016, http://www.chimurenga.co.za/about-us.) The print magazine has grown to encompass a number of different editorial and curatorial activities that traverse digital, printed, and “real” space, including themed performances called Chimurenga Sessions; an online music radio station and live studio known as the Pan African Space Station (PASS); and the Chimurenga Library, an ongoing project that interrogates the public and informational space of the library, supplementing it with a compendium of historical and current African periodicals. Discussing the relationship between online and printed distribution, Edjabe has stated, “it was important for us to exist in print, in order to make the intervention we needed to make in the body of written material on and/or from Africas. But I also feel the debate between online and print is an old debate. I don’t think one excludes the other, and that’s the approach we chose. To have a presence in both spheres.”(Ntone Edjabe, “Chimurenga: who no know go know.” Interviewed by Dídac P. Lagarriga, An interview with Ntone Edjabe. Oozebap, accessed August 10, 2016, http://www.oozebap.org/text/chimurenga.htm)

Chimurenga has intervened into the material and informational structure of the media with projects such as The Chimurenga Chronic (2011), which was originally published as an issue of Chimurenga Magazine, and conceived as a “one-off edition of an imaginary newspaper” that attempted to challenge the newspaper’s history as an instrument of nationalism and destabilize its claims to historical truth. Set in the past, during the week of May 18-24, 2008, when a series of violent xenophobic riots and attacks swept South Africa, the Chimurenga Chronic challenges received historical narratives and mainstream reporting about the events of that week, while seeking to reactivate that history as a critical force in the present. The project has since evolved into a quarterly publication, fostering progressive and critical discourse internationally on Africa. As Edjabe wrote: “We recognized the newspaper—a popular medium that raises the perennial question of news and newness, of how we define both the now and history…We selected the medium both for its disposability and its longevity, its ability to fashion routine in a way that allows us to traverse, challenge and negotiate liminality in everyday life.”(Ntone Edjabe, letter to readers and collaborators of Chimurenga, January 2013, in Gwen Allen, ed., The Magazine (Cambridge and London: MIT Press and the Whitechapel Gallery, 2016).)

As these examples attest, publications do not merely represent or report on events but can themselves be important sites of human action and agency. This is the premise behind Chto Delat? the eponymous broadsheet (also distributed online at https://chtodelat.org/) launched by the St. Petersburg-based artistic collective in 2003 in order to protest the conservative consumerism of Putinist Russia and to repoliticize intellectual and artistic culture. According to the artist Dmitry Vilensky who helped to found both the group and publication, the periodical was “an ideal means of expression” for the collective work and activism they wished to undertake—a process that, significantly, began with a question rather than an answer.(Dmitry Vilensky, “A dialogue between Viktor Miziano and Dmitry Vilensky: Singular together!” in Chto Delat? In Baden-Baden – The Lesson on Dis-Content (Baden-Baden: Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, 2011), 35.) The Russian phrase “Chto Delat?” (translated into English as “What is to Be Done? Or “Where To Begin?”) references Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s nineteenth century novel of the same title, as well as Vladimir Lenin’s 1901 political pamphlet in which he discussed the potential of the newspaper as a site of revolutionary struggle. Chto Delat? draws on Lenin’s notion of the newspaper as a “collective organizer,” in its understanding of the publication as an instrument not only of political discourse but also activism. Comparing the role of the newspaper to that of scaffolding erected around a building, which enables construction and facilitates the movement and communication of the builders, Vilensky explains, “In the process of making something you already build and construct your constituents.”(Dmitry Vilensky, “Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today” (Conference), American University of Beirut, March 7-8, 2014.) This description captures how Chto Delat?—along with so many of the other publications discussed here—rethinks the means and ends of publishing. Rather than representing a pre-existing collective or public, they bring it into being as something that cannot be quantified or fully known ahead of time. In this sense, they counter the instrumentalization of the public sphere for predetermined ends or profit, admitting contingency and indeterminacy into the very act of communication.

As these examples attest, publications do not merely represent or report on events but can themselves be important sites of human action and agency. This is the premise behind Chto Delat? the eponymous broadsheet (also distributed online at https://chtodelat.org/) launched by the St. Petersburg-based artistic collective in 2003 in order to protest the conservative consumerism of Putinist Russia and to repoliticize intellectual and artistic culture. According to the artist Dmitry Vilensky who helped to found both the group and publication, the periodical was “an ideal means of expression” for the collective work and activism they wished to undertake—a process that, significantly, began with a question rather than an answer.(Dmitry Vilensky, “A dialogue between Viktor Miziano and Dmitry Vilensky: Singular together!” in Chto Delat? In Baden-Baden – The Lesson on Dis-Content (Baden-Baden: Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, 2011), 35.) The Russian phrase “Chto Delat?” (translated into English as “What is to Be Done? Or “Where To Begin?”) references Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s nineteenth century novel of the same title, as well as Vladimir Lenin’s 1901 political pamphlet in which he discussed the potential of the newspaper as a site of revolutionary struggle. Chto Delat? draws on Lenin’s notion of the newspaper as a “collective organizer,” in its understanding of the publication as an instrument not only of political discourse but also activism. Comparing the role of the newspaper to that of scaffolding erected around a building, which enables construction and facilitates the movement and communication of the builders, Vilensky explains, “In the process of making something you already build and construct your constituents.”(Dmitry Vilensky, “Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today” (Conference), American University of Beirut, March 7-8, 2014.) This description captures how Chto Delat?—along with so many of the other publications discussed here—rethinks the means and ends of publishing. Rather than representing a pre-existing collective or public, they bring it into being as something that cannot be quantified or fully known ahead of time. In this sense, they counter the instrumentalization of the public sphere for predetermined ends or profit, admitting contingency and indeterminacy into the very act of communication.

This essay has tried to think about some of the ways in which publications operate critically to foster publics, both within the contemporary art world and beyond it. At the same time, it can be difficult to evaluate or determine their precise audience and impact, since in many cases their circulations are very small and/or impossible to quantify due to online and unofficial forms of distribution.(The circulation and print runs of the publications discussed here vary and I was not able to track down figures for all of them: Gahnama-E-Hunar had a print run as high as 1,200; Pages prints 1,000 copies of each issue; Chto Delat has varied from 1,000 to 10,000, but averages 2,500.) Online distribution in particular has altered the traditional ways in which information is contextualized, uprooting communication from any single measurable context or material substrate.(For a discussion of the complexities of online distribution, see Colby Chamberlain and Triple Canopy, “The Binder and the Server” Art Journal, Winter 2011, pp. 40-57.) Indeed, publications today span and traverse multiple places, contexts, audiences, languages, distribution forms, and media platforms. Yet, even as they de-essentialize and deterritorialize conventional definitions of place and audience around which publics have traditionally been mobilized, the critical publications discussed above also seek to create new contexts for information and communication, and to acknowledge the historicity and politics of distribution forms and media. While it is problematic to generalize such a diverse group of publications, one of the things that a number of them share is the deliberateness and self-reflexivity with which they approach the activity of publishing itself. In this sense, they can be understood in relationship to a larger history of publishing practices that conceived of the periodical not merely as a means or instrument of communication but as a medium, the conventions of which were not taken for granted or naturalized, but tested and rediscovered or invented anew.(I am thinking in particular of artists’ magazines from the 1960s and 1970s, such as Aspen, 0 To 9, FILE, as well as projects by artists such as Dan Graham, Adrian Piper from this period, which used periodicals as an artistic medium. Also see the first part of this article, “Art Periodicals and Art Worlds, Part 1: An Historical Exploration.”) This history may itself function as an important source of criticality, by offering precedents and frameworks for current publishing practices, which may in turn reactivate this past, and make it newly meaningful in the present.