Alternative Identities: Conceptual Transformations in Soviet and Post-Soviet Architecture

The development of Russian architecture, from the neo-classicism of the 1950s to the postmodern trends of the 1990s, followed socialist and post-socialist economic and political cycles. Soviet architecture was essentially an element in the socio-political process of the construction of communism. The ideological blueprint for Soviet architecture was introduced during the earliest years of the Soviet Union when what was important in architecture was architecture’s political content rather than its structural laws or those of its physical environment.

In the early socialist age, new models of living space were developed which the architects defined as spaces for the collective. In the 1930s, architecture became a hermetically sealed cultural domain, and one in which conservative tendencies prevailed. All access to publications containing Western modernist architecture was made extremely difficult.

In the Soviet Union, Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy was used by the authorities to suppress all alternative ways of thinking. General lines of development in architecture and elsewhere were dictated from above, starting Stalin’s plans for reconstructing Moscow (which included a large number of governmental projects, such as the Palace of Soviets and other prestigious high-risers), Khrushchev’s reform of the standards in housing construction, and Brezhnev’s housing programs of 1971-80.

By the end of the 1970s, the excitement about the role of architecture in the socialist state gave way to a more sober understanding of its situation. A professional crisis that had been visible before only from outside the Soviet Union suddenly became a reality on the inside.

Protesting against corrupt state architecture, tedious standardized production, and a barren ideological legacy, a group of young Russian architects united in the so-called “paper architecture” movement of the late 1980s. In their work, which is often ironic and which existed only on paper, parallels to the architecture of the early Soviet days as well as other historical styles are apparent.

While the generation of the 1960s used architecture to improve reality, the paper architects of the first decade after perestroika withdrew into the beautiful, magic world of paper architecture, opposing official Soviet architecture through their neo-constructivist designs, deconstructive or historicist replicas, and postmodern contextualizations.

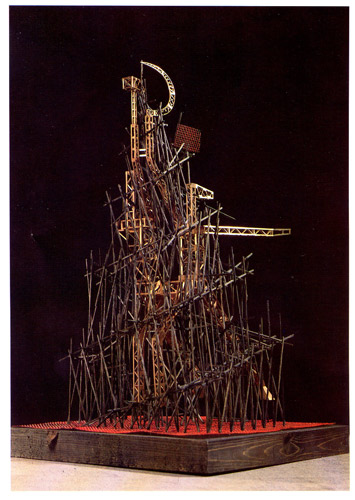

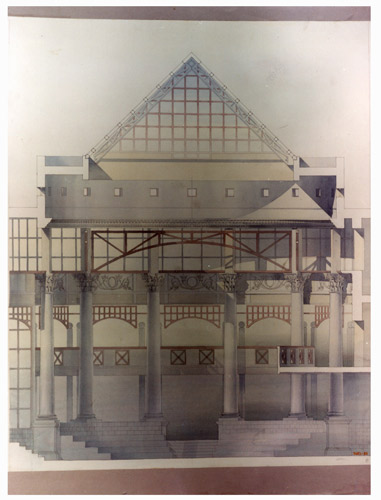

To give an example, Yuri Avvakumov’s Tower of Perestroika was created for the exhibition “Temporary Monuments” at the Russian Museum in St.Petersburg. It was designed in 1990 as an ironic reminiscence of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International which wraps around Mukhina’s Monument to Worker and Farmer, a popular icon of Socialist Realism. Like Igor Khatuntsev’s Cathedral (1991), Avvakumov’s Tower can be seen as a symbol of the transition from Socialism to Post-Socialism. Soon Russian paper architecture merged with the architecture of postmodernism in the West and many Russian paper architects went on to win prestigious awards in professional competitions around the world. While the authorities derided “paper architecture” as nothing more than school exercises many of Russia’s best young architects resettled in the West.

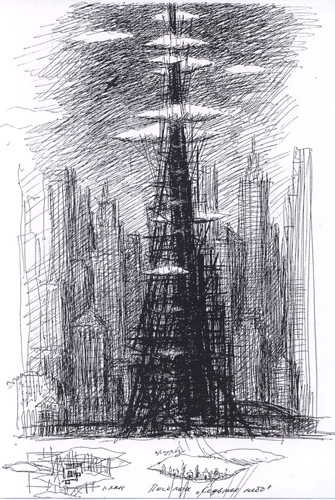

The principles on which paper architects based their work included symbols such as “the light at the end of the tunnel” and “the path toward the temple” as we find it in Tengiz Abuladze’s film Repentance (1987). In Abuladze’s film, hyperbole creates an unforgettable image of the socialist era and its people. Paper architects used it in their effort to salvage Russian architecture. Additionally, in the 1980s, there were Neo-Futurist disputes concerning “harmonious urban planning” and the creation of new patterns for residential space. In 1992, Igor Khatuntsev embodied his architectural dream in a skyscraper whose separate apartments are shaped like clouds, a playful use of nature as part of an architectural edifice.

A more somber version of the urban future was designed by Igor Khatuntsev in 1993. “The Robot Factory”, a fantastic industrial vision, states that everything is predictable, and that machines satisfy all needs of urban life. Khatuntsev also created a series of shelters for surviving catastrophes.

The paper architects succeeded in creating a new image of the artist in Russian society where artists traditionally either played the role of prophets and truth-fighters, or served the authorities. Yet, in the 1990s, with new changes in the economic field, their situation changed drastically. In the early 1990s, municipal authorities dismissed 40% of Moscow’s architects; only a few of them were able to set up their own studios. There was considerable competition and long delays for being granted a work license. Some of the former paper-architects, such as Alexey Bavykin, Sergei Kiselev, Evgeni Krupin, Andrei Miroshin, and Evgeni Velichkin, subsequently became architects for the “new Russians” and succeeded in transforming their paper dreams into real life buildings. Like Evgeni Velichkin and Nikolai Golovanov of the A&A Workshops who designed villas for the “new Russians”, paper architects never revealed the names of their wealthy clients. The names of the investors for such high-profile projects as the Theater Center on Moscow’s Garden Ring also remained confidential. This kind of “wild” capitalism speaks to the criminal connections that existed between the new businesses and the Mafia.

After the brief democratic moment of the late 1980s, then president Boris Yeltsin urged the country to concentrate again on its national legacy. This nationalist call for history and tradition as the basis for political consolidation was also reflected in architectural politics where modernism and international style were repudiated in favor of things “Russian”. The new leaders in the architectural hierarchy declared that the appeal to national history rescued Russia from the evil of (Soviet) modernism, with its dogma of standardized production and industrial egalitarianism. Yet while the national architectural “legacy” was declared the conceptual source for all new architecture, there was neither the political will nor the means for the conservation and preservation of historical buildings, even whole city districts; much of the valuable historic environment was destroyed and replaced by cheap reconstructions.

As a result of Yeltsin’s call, the imitation of stereotypical traditional styles became a common decorative technique in architecture, which in its superficiality was incapable of changing the essence of architectural and urban spaces. The mass return to architectural traditions, recognizable symbols, and historicist allusions signaled the decline of professional culture, as well as an architectural crisis in the post-Soviet Russia of the late 1980s-1990s. The modernist origins of paper architecture were excised. The newly born “Luzhkov style” provoked discussions within intellectual communities both in the East and in the West: Is this neo-eclecticism or kitsch? Are the symptoms of postmodernism necessarily evil reflections of the market economy, the image of new national identities, or simply a sign of professional incompetence?

<pclass=”body”> Even when the opportunity for individual initiative arose, Russian architects, too deeply immersed in standardized design, simply continued the barren legacy of tasteless constructions that had been (re)-produced over the course of many years. As Mikhail Tumarkin writes, “When culture flees, its place is taken by an […] triviality” (“Russland”, 85). The downward trend in Russian architectural construction at this time was also reflected in the decay of design.

At the same time, expanding market relations stimulated joint ventures and foreign investments in architecture and the construction sector. The construction of the postmodern McDonald’s Headquarters in downtown Moscow was completed in 1993, and in 1998/99 a shopping center of the Nautilus Co. was built on Lubyanskaya Square in Moscow. The ABV Group under the leadership of Alexey Vorontsov, the director of General Architectural Planning Department of Moscow, was in charge of both projects. The multitude of architectural forms, materials, colors, and textures in this building overwhelmed the public’s expectations. While the design recalled the scandalous “culinary masterpieces” of Hans Hollein and James Sterling (known museums in Cologne and Berlin, respectively) that were created in the 1980s, its authors claimed that the building was connected with the restored Nikolskaya Tower and a part of the Kitai-gorod wall that had been demolished in the thirties-claims that were viewed skeptically by Moscow’s professional community.

In the 1990s, former Russian paper architects kept their positions, but stayed largely in the wings. In 1999, some of them who were actively involved in the new architectural processes (such as the directors of the architectural studios, Evgeni Ass and Alexander Asadov, or Boris Levyant, the president of “ABD+SPGA”) gathered for a series of roundtable talks where they discussed the need to satisfy their new clients by inventing facades, developing postmodern figurativeness, and imitating historical styles. Eager to develop a professional culture for architecture in Russia, the former paper architects seem to place great expectations on their wealthy new clients.

Bibliography

1. Castillo, Greg. “Constructivism and the Stalinist Company Town.” Urban Design Studies, Volume 2, 1996. 1-20.

2. Rappaport, Alexander G. “Language and Architecture of Post-Totalitarism.” Paper Architecture: New Projects from the Soviet Union. Ed. Heinrich Klotz. New York: Rizzoli, 1990.

3. “Russland”-Heft. Der Architekt. Zeitschrift des Bundes Deutscher Architekten 2, A 12230 E, (1994): 69-113. In German.

4. Sokolina, Anna. “Russia in Transition: Residential Construction, Law, and Market.” Kommune. Forum for Policy, Economy, Culture 10 (1993): 52-55. Frankfurt/Main. In German.

5. Sokolina, Anna. “From Paper Architecture to Joint Venture.” Bauwelt 48, 28 Dec. (1992): 2733-2741. Berlin. In German.