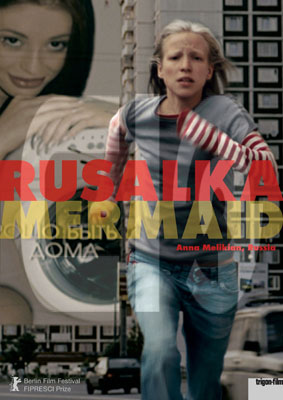

A Little Mermaid in the World of Russian Advertising (“Rusalka” Roundtable, #5)

Rusalka/Mermaid (2007), the second feature film by director Anna Melikyan, has been chosen as Russia’s entry for the Foreign Oscars in 2009. It has already received ample recognition at the Russian box office and has also won several awards in 2008, among them the World Cinema Directing Award at Sundance and the grand prize for the best film in the international competition in Sofia.

Alisa is growing up without a father in a beach shack on the Black Sea. She wants to become a ballerina but her mother causes her to be late for the audition. Alisa develops the qualities of an outsider, does not get along with her mother. Sheplans to denigrate her mother in front of her dad when he at last comes back. But her father, a sailor who obviously does not even know about her existence, never returns. Due to her frustration growing up, Alisa stops talking but mysteriously develops a magical ability to fulfill wishes. When her family moves to Moscow she meets an advertising specialist named Alexander. She saves his life at a moment when he, in a drunken state, wants to drown himself in the river. She accompanies him to his apartment and the next morning he mistakes her for a cleaning woman. Alisa falls in love with Alexander, dyes her hair green, helps him market properties on the moon and saves his life two more times. When a car hits her in the street, her body disappears from the frame.

Alisa is growing up without a father in a beach shack on the Black Sea. She wants to become a ballerina but her mother causes her to be late for the audition. Alisa develops the qualities of an outsider, does not get along with her mother. Sheplans to denigrate her mother in front of her dad when he at last comes back. But her father, a sailor who obviously does not even know about her existence, never returns. Due to her frustration growing up, Alisa stops talking but mysteriously develops a magical ability to fulfill wishes. When her family moves to Moscow she meets an advertising specialist named Alexander. She saves his life at a moment when he, in a drunken state, wants to drown himself in the river. She accompanies him to his apartment and the next morning he mistakes her for a cleaning woman. Alisa falls in love with Alexander, dyes her hair green, helps him market properties on the moon and saves his life two more times. When a car hits her in the street, her body disappears from the frame.

Festivals and young audiences on Russian blogs thoroughly adore the “endearing” introvert Alisa. Most critics appreciate the movie’s “abundant charm and digital trickery in the Amelie mold.”(Russell Edwards on http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117934944.html?categoryid=31&cs=1.) The film also won the Critics’ Prize FIPRESCI at the Berlinale 2008. It was not included in the shortlist of foreign-language films in the Oscar voters’ nominations, though. I was invited by the Free University Berlin to talk about the film in the context of a project called Post Soviet New Man (and Woman).

Visually, the film is attractive and well-crafted. Its “look” is achieved by a digital process that renders the Black Sea- sequences luscious while the Moscow scenes are grey. The city’s de-saturated palette allows the filmmaker to designate patches of green as “mermaid color,” contrasts with the drab urban environment and is visible only to Alexander.

The soundtrack by St. Petersburg composer Igor Vdovin, who previously worked with Renata Litvinova and Aleksey German Jr., is surprisingly likeable.(“18” on the playlist available at http://profile.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=user.viewprofile&friendID=168480071.) It is based on a simple but catchy tune that brings to mind teenage adventure films of the ‘70s. The score stresses the infantile, lighter side of Alisa’s character. The whimsically optimistic flute underlines humorous aspects of the film, which is, after all, meant to be a “tragical comedy.”

There is nevertheless something slightly annoying about Rusalka. At first I could not quite tell what it was. Among the reviews I found, there was one that confirmed my overall impression: the “fairy tale aspires to be something like a Russian Amélie but its erratic protagonist (despite her wonderful smile) is not as endearing as she should be, and the film never finds a comfortable rhythm.”(Darell Hartman, “From Utah With Love”, January 25, 2008. New York Sun, http://www.nysun.com/arts/from-utah-with-love/70212/.)

The film does not quite cope with the challenge of its genre (“tragical comedy”). As a remake of an old fairytale by Andersen, the film misses a great opportunity to rethink the gender stereotypes present in its 19th century precursor. It was somewhat painful to see how the genre and the script force the “little Moscow mermaid” to her knees, especially considering that this is a film by an ambitious young female director. Melikyan wrote the screenplay for Rusalka in collaboration with a female colleague, Natalia Nazarova.(Nazarova wrote the script for another film with a provincial girl coming to Moscow. In Slushaya tishinu/Listening to the Silence (dir. by Aleksandr Kasatkin 2007) the girl aiming at composing becomes a chambermaid: It was produced by the same company as Mermaid: Central Partnership.)

Upon awakening, Prince Alexander finds in his apartment an urchin girl in a striped vest with his flokati rug wrapped around her hips, and he mistakes Alisa for a cleaning lady. Instead of explaining that just a few hours ago she saved his life, she whines, “I am a ballerina.” Alexander replies, “To my mind, you’re a fool.” (“Po-moemu, ty dura”). This might be a realistic representation of an encounter between a provincial girl and a Moscow yuppie. However, I found it hard to accept that the little mermaid, whom I came to associate with everything ethereal and enchanting, took to cleaning like a duck to water. The moment she accepts the money for her work, the viewer senses that this is going to be a very one-sided love story. In this cynical turn of the plotline, Melikyan and Nazarova’s script reveals its weakness. The story keeps evolving in that vein until it’s time to bring the film to an end, at which point the heroine is simply killed off. Although Alisa thinks that Alexander and she are meant for each other, the sad reality of the story is a simple and prosaic truth: there is no way a rich Moscovite would get seriously involved with a scrawny kid from the Krasnodar region, at least not in a sober state of mind.

Upon awakening, Prince Alexander finds in his apartment an urchin girl in a striped vest with his flokati rug wrapped around her hips, and he mistakes Alisa for a cleaning lady. Instead of explaining that just a few hours ago she saved his life, she whines, “I am a ballerina.” Alexander replies, “To my mind, you’re a fool.” (“Po-moemu, ty dura”). This might be a realistic representation of an encounter between a provincial girl and a Moscow yuppie. However, I found it hard to accept that the little mermaid, whom I came to associate with everything ethereal and enchanting, took to cleaning like a duck to water. The moment she accepts the money for her work, the viewer senses that this is going to be a very one-sided love story. In this cynical turn of the plotline, Melikyan and Nazarova’s script reveals its weakness. The story keeps evolving in that vein until it’s time to bring the film to an end, at which point the heroine is simply killed off. Although Alisa thinks that Alexander and she are meant for each other, the sad reality of the story is a simple and prosaic truth: there is no way a rich Moscovite would get seriously involved with a scrawny kid from the Krasnodar region, at least not in a sober state of mind.

Aesthetically, the film is very similar to European art-house. It is the kind of look that most people in the West choosing to watch a Russian film want to avoid. Interestingly, there is a striking similarity between the way in which Rusalka is marketed (at least in Western Europe) and the German film Run Lola Run (directed by Tom Tykwer, 1998). Running through the city to save her Beloved One, Alisa seems to take on Lola’s baton.

Watching the final scene of Rusalka I was reminded of another film by Tykwer, Heaven (2002), which also ends with an “ascension” of the main character. Based on an unfinished project by Krzysztof Piesiewicz and Krzysztof Kie?lowski, Heaven benefits from the strong performance of Cate Blanchett in the lead role of the teacher Philippa who fights the drug mafia in Italy. In Heaven, it is not exactly clear what happens to Philippa and her boyfriend in the end, when they both “go to heaven” by fleeing in a helicopter. But even assuming that they died, the viewer still can feel some relief knowing that in her death the righteous drug-mafia fighter Philippa is united with her young lover, the carabiniere (Giovanni Ribisi).

In Melikyan’s film, the heroine’s death has no meaning. A street kid ran in front of a car and was swirled away. Worse yet is the dummy, catapulted into the air, which is neither a sublime image (compared to the spiraling helicopter in Heaven) nor a catastrophic climax for a story (as in the fall of the son in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s powerful film The Return/Vozvrashcheniye, 2003, also a coming-of-age story ending in death). The double of Alisa’s girlish body gets torn to pieces so rapidly that this ultra-short shot looks like a visual gag.

Did Alisa’s life and death matter at all? In what might be a symbolic embodiment of current Russian hyper-materialism, she helps secure the wealth and wellbeing of a thriving young businessman, first, by fishing him out of the river, then by looking after his flat, by warning him not to take a flight that is bound to crash, and at last by disappearing at the right moment. At times, the script seems to endorse this version without any irony, forgetting that the film aspires to be a social critique: a provincial girl being swallowed by the machinery of the new Russia (a sad ending, just as in other Andersen tales). There could have been a more Kieslowskian, mystical end if Alexander began to falter after the death of his guardian angel. But for the story of a contemporary mermaid, a happy end with a romantic union of Alexander and Alisa is unthinkable, and even an ambiguous finale as in Run Lola Run does not seem to be an option. Its prosaic ending makes Rusalka noting but another cautionary tale about the perils of a provincial girl in the big city.

This short biography of a girl from the Black Sea meticulously follows Andersen’s “Little Mermaid,” replicating the tale’s depressing ending. Getting to know Alisa we expect something else: perhaps a story in the vein of the Russian fairytale about Ivan-Durachok, an amiable simpleton who finds his happy lot after many hardships. Alisa in fact is modeled after a similar hero. She is sent to a special school for mentally challenged children and Alexander blatantly calls her an idiot. But there is a problem: she is a female and lacks the overwhelming luck of the robust Ivan. Alisa may also remind Russian audiences of the foolish girl in Tarkovsky’s Andrey Rublev (1966) who runs after the first man that crosses her path. As it is the case in Andersen’s film, not only does the heroine fail to win the Prince, she cannot even survive Moscow for a long period of time.

Alexander, the Mermaid’s Prince, is a typical representative of the smart and slick elite of the Moscow business world. His down-to-earth character does not make him less desirable for the mermaid from Anapa who seems uninterested in money but who is interested in good looks (this theme stemming from the rusalki in Russian folklore who try to lure young, handsome men into the water).

Since nobody in Rusalka remembers the girl after her tragic death and since her care for Alexander is never fully revealed to him, Alisa’s destiny echoes the Little Mermaid’s sacrifice. We soon lose connection with the film which until this point has been narrated from the point of view of the main protagonist. Alexander never even learns of Alisa’s accident. The fact that they are the only people who mourn Alisa surely weighs heavily on the film’s spectators who are left to deal with an abrupt end not only to her life, but also to her way of looking at things. A poor replacement for Alisa’s voice is a digitally manipulated image that looks like a colorful postcard of her smiling at the beach in the final shot: perhaps this is meant to be Alisa in heaven?

In Tykwer’s Heaven, the policeman’s father (also a policeman) meets the couple before their anticipated death to bless their decision and is awed by her desperate situation and the intensity of the love they share. He will keep their memory. But nobody will remember Rusalka. Even the man whose life she saved several times has already forgotten her by the end of the film. When we hear him talking to his glamorous girlfriend we know that he has already purged his human talisman from his mind. To the businessman, forgetting happens quite naturally. The viewer knows that Alisa was his guardian angel. Yet Alisa is a mermaid and not an angel. This is why her death after being hit by the car does not bring any closure.

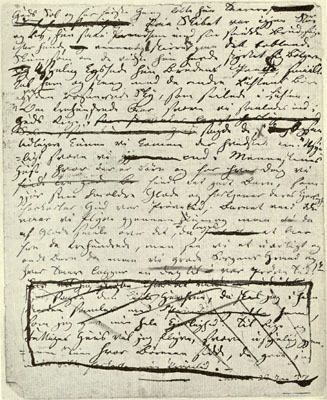

The only clue to the ending is probably to be found in Andersen’s “Little Mermaid,” which has one often overlooked detail: after her death, the mermaid turns into “a daughter of the air,” “earning an eternal soul” by doing good deeds. Does the same happen to Alisa whose face high up in the air on a billboard is earning rubles for Alexander? It is not quite clear whether Andersen initially planned such a Christian ending to his tale (earning a soul with “good deeds”). 20th-century readers criticized his story for being too moralistic.(“But–a year taken off when a child behaves; a tear shed and a day added whenever a child is naughty? Andersen, this is blackmail. And the children know it, and say nothing. There’s magnanimity for you” (Pamela Lyndon Travers, “The Primary World” In Parabola 4, 3: 1979, 93).) It is known that Andersen originally ended the fairy tale with the mermaid dissolving into foam, only later adding the “daughters of air”. The last page of Andersen’s manuscript shows that he was not so sure what the ending should look like.

The only clue to the ending is probably to be found in Andersen’s “Little Mermaid,” which has one often overlooked detail: after her death, the mermaid turns into “a daughter of the air,” “earning an eternal soul” by doing good deeds. Does the same happen to Alisa whose face high up in the air on a billboard is earning rubles for Alexander? It is not quite clear whether Andersen initially planned such a Christian ending to his tale (earning a soul with “good deeds”). 20th-century readers criticized his story for being too moralistic.(“But–a year taken off when a child behaves; a tear shed and a day added whenever a child is naughty? Andersen, this is blackmail. And the children know it, and say nothing. There’s magnanimity for you” (Pamela Lyndon Travers, “The Primary World” In Parabola 4, 3: 1979, 93).) It is known that Andersen originally ended the fairy tale with the mermaid dissolving into foam, only later adding the “daughters of air”. The last page of Andersen’s manuscript shows that he was not so sure what the ending should look like.

Strictly speaking, there are three versions of the Little Mermaid story: the mermaid turns into foam; she earns a human soul through good deeds (the Christian variant); or the Disney-style happy ending. It is all the more striking that the woman director of Rusalka insists on Andersen’s conservative moralistic version, sending the girl into the sky “to earn a soul” by good deeds.

A possible visual parallel to Rusalka is Khutsiev’s film Iyulski dozhd (July Rain, a 1966 masterpiece among the small assortment of Russian nouvelle vogue films). July Rain starts out with a young woman running through Moscow. Behind her we see huge ads – in Moscow during the 1960s billboards were becoming an increasingly common part of the urban landscape. The mise-en-scene stresses the heroine’s independence, and the ads seem to form a wallpaper-like background design. She moves gracefully in front of the billboards, separated through her movement from the current of the crowd overtaking the other pedestrians.

In Rusalka, too, advertising plays a crucial role, even making it into the story when Alisa walks around dressed as a cell phone for an advertisement. She later becomes the “face” of the Moon Girl, helping her beloved sell properties on the moon to wealthy New Russians (“the lot between Reagan and Tyson is still available.”) Like Alisa, the viewer is compelled to read ads and banners such as “Follow your star” or “Everything will be ok” as a direct comment on the story. Written by ad-men and “PR’schiki” like Alexander, the ads are actually not addressed to her, the poor girl who cannot buy anything.

Andersen’s “Little Mermaid” ends by using its underlying Christian ideas to make up for the loss of the desired object. The mermaid has a choice: either to kill the Prince (this is the recommendation from her less prissy sisters) or to die herself by turning into foam. She chose the latter and sacrifices herself for the Prince even though he has forgotten all about her and moved on to another girl.

Rusalka could have become a rather serious film in one of two ways: if the main character had a strong on-screen presence, or if a well written script had carried her through the film. As it is, the screenplay drowns her. But perhaps this is exactly what the film aspires to do: dissolve the heroine in the plot and even take away her idiosyncratic storytelling. After she had disappeared into thin air, the audience hears her precocious voice talking from heaven for the last time. After that, she is simply mute.

The heroine’s fairytale-inspired quirkiness and the cynical outcome of the story do not combine well. But again, the film seems to be realistic if we think about contemporary life in the Russian capital where fantasy and reality, provincial naiveté and newly acquired shrewdness, unbelievable miracles and tragic accidents seem to mingle at every street corner.

The best part of the movie is a series of melancholic jokes about the New Russian world of “PR” (“Piyar”) and advertising taking over life. At one point Alisa cuts a hole into a billboard so she can see out of the window of her apartment. Then her ancient grandmother, who survives Alisa, chooses this window in the eye of the ad as her favorite place to sit. Another bitter joke occurs when the Mermaid becomes the Moon Face in the gigantic ad on a Moscow high-rise, signaling the disappearance of a provincial girl who did not make it in the big city. Paper-thin as she was, she only “made it” in the two-dimensional world of advertising. In this capacity, she is successfully utilized by her prince for some time after her death.

The best part of the movie is a series of melancholic jokes about the New Russian world of “PR” (“Piyar”) and advertising taking over life. At one point Alisa cuts a hole into a billboard so she can see out of the window of her apartment. Then her ancient grandmother, who survives Alisa, chooses this window in the eye of the ad as her favorite place to sit. Another bitter joke occurs when the Mermaid becomes the Moon Face in the gigantic ad on a Moscow high-rise, signaling the disappearance of a provincial girl who did not make it in the big city. Paper-thin as she was, she only “made it” in the two-dimensional world of advertising. In this capacity, she is successfully utilized by her prince for some time after her death.

Roundtable Participants:

Natascha Drubek-Meyer, A Little Mermaid in the World of Russian Advertising

Matthias Meindl and Svetlana Sirotinina, Theodor Adorno, Fairy Tales, and “Rusalka”

Christine Goelz, A Modern Fairy Tale

Henrike Schmidt, Happy End

Bettina Lange, Glamor Discourse