Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany

Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany at the Tweed Museum of Art, Duluth, Minnesota, February 2–May 15, 2022

In Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany, curators Sara Blaylock and Sarah James assembled a comprehensive body of art from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) that functioned as more than an art historical survey, raising larger questions about the relationship between artists and social and political institutions. The exhibition presented works by over thirty artists and artist groups active in the 1980s and early 90s. Rather than focus on better-known painters such as Willi Sitte, Werner Tübke, or Bernhard Heisig, the show presented artists working on the margins or in the underground of the East German artworld, particularly those who used more ephemeral media and worked collaboratively. The media in question— works on paper, photography, and publications— reflect a concern with reproducibility and distribution, integrating artmaking into everyday life, and efforts to circumvent the state’s surveillance and control of cultural production.

Installation view of Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany, entrance and room 2. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art. Photograph by Charles Walbridge.

The GDR’s de facto absorption into the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990 in many ways led to the erasure of its history. The roughly 40 years of the GDR’s existence, including its cultural products, were seen as an aberration or as a mere side note to a greater, continuous German history. It is only relatively recently that the work of either experimental or established GDR artists has begun to be viewed as a legitimate, separate cultural expression. This exhibition marks one of the first efforts to bring the work of the GDR’s alternative art scenes to a US audience, providing a rare opportunity for viewers to acquaint themselves with this work and its historical context. The curators addressed the audience’s potential lack of familiarity with GDR culture—the University of Minnesota at Duluth’s Tweed Museum of Art is located on the college campus—in three thematically organized rooms—art from inside and outside the academy, artistic publications, and collaborative practices—that provided a throughline without becoming overly didactic.

Installation view of works by Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Mid-1970s. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art. Photograph by Charles Walbridge.

The first room introduced viewers to the dynamic of the East German artworld through the work of Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt and Jürgen Schieferdecker. Wolf-Rehfeldt comes from outside the established GDR art training system, which admitted only limited numbers of students. Although Wolf-Rehfledt had no formal art education, she was still able to exhibit some of her work and gained admittance to the GDR’s Artists’ Union in 1978. Schieferdecker’s career meanwhile followed a more conventional path, with a degree in architecture from Dresden’s Technical University, admittance to the Artists’ Union in 1977, and employment as an art professor at his alma mater in 1993.

Wolf-Rehfeldt used the typewriter as a drawing tool to produce small-scale works that encompass concrete poetry and semantic wordplay, abstract patterns, and optical illusions, as well as representational images. These were produced as individual or limited-edition works using carbon paper. Wolf-Rehfeldt’s virtuosity with the typewriter is on display, for example, in a work like Atomic Tree from the mid-1970s where she uses the punctuation marks and black-and-red inks of the typewriter ribbon to render what reads as both a mushroom cloud and a tree, likely referencing the Japanese White Pine bonsai that survived the bombing of Hiroshima by the US. The anti-nuclear sentiment and symbolism of this work fit well within the GDR government’s framing of the GDR as a peace-loving nation through its anti-war posters, creating a space from which Wolf-Rehfeldt could offer her more personalized anxieties on the subject. In other works, the artist’s choice of words (e.g. “we shall overcome” in a 1970s work memorializing Martin Luther King Jr.) both adheres to the protocols of international, cross-racial solidarity and offers an implicit critique of the regime’s own civil rights’ hypocrisies.

Schieferdecker’s lithographs, influenced by Dada and Pop Art, incorporate a variety of collage techniques to bring everyday materials like newspaper clippings and maps into conversation with drawings and art historical references. For example, Continental Art No. 4: DOR from the 1979 portfolio Politische Grafik (Political Graphics) combines a reproduction of Anselm Feuerbach’s 1862 painting Iphigenia superimposed on a map of Germany in negative. The ground for these images is the front page of the official GDR communist party newspaper Neues Deutschland featuring an article about an arts congress in the newspaper’s lower-left corner. Imposed on top of this article is a line graph with an X-axis of numbers starting with “49” (the year of the GDR’s founding) and ending with “79” (the year of this artwork and the 30th anniversary of the GDR) whose dateline is formed by the stem of a red rose that extends to the rose’s blossom in an exponential curve. Schieferdecker’s interests in art history and political critique come together in this work, which looks at the development of German art after the country’s division following World War II.

Installation view of Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany, room 2. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art.

In their works, Wolf-Rehfeldt and Schieferdecker walk a careful line; neither displays obvious state-supporting or state-critiquing propagandistic tendencies that a US-American viewer might expect or want from East German artists, yet their work is not unpolitical, let alone apolitical. Both worked within the constraints imposed upon them by the highly bureaucratized GDR cultural sector, yet Wolf-Rehfeldt’s career especially demonstrates that some degree of independence and room for societal critique could be established within these constraints.

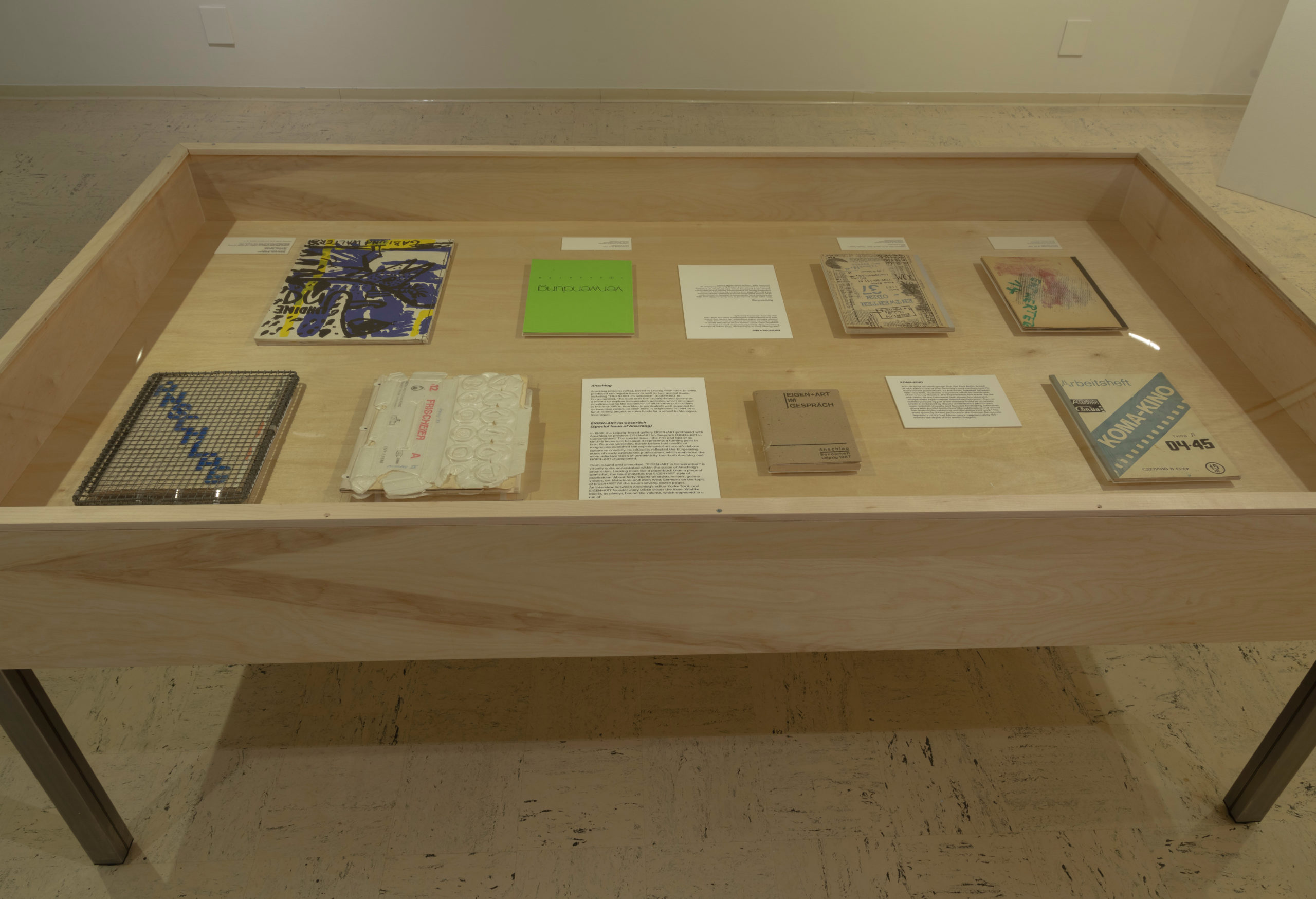

Vitrine in room 2 with copies of publications. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art.

The exhibition’s second section focused on publications as an artistic format that could circumvent some forms of state control. For instance, publications produced as “artistic portfolios” avoided the need for printing permissions that traditional books required, creating space for content that might not otherwise be supported by the state. An amazing breadth of work was included in this section, with formats ranging from limited-edition folios to short-run books, to regularly published periodicals and journals, to one-of-a-kind artist books. The exhibition of these publications also highlighted the role of artist collectives like Clara Mosch (active 1977–82) in Karl-Marx-Stadt, and art spaces such as Eigen + Art in Leipzig (1983–present) in their production and conception. Viewers were able to see in these objects not only the work of the artists involved, but they also caught a glimpse of the artistic discourse that inspired them, particularly outside of the artistic and literary enclave of East Berlin.

The publications, including Koma-Kino, Entwerter/Oder, Verwendung, and others, were presented in glass vitrines. Unfortunately, viewers could not leaf through them, and most publications were presented with their covers closed, so that the contents remained unseen. With the exception of two issues of the magazine Anschlag featuring unusual bindings—one using Styrofoam egg cartons, the other using a metal contraption used for grilling sandwiches—most of the publications’ covers were not visually remarkable in a way that might helped shed light on the East German art scene. On the other hand, the thoughtful descriptions included in the vitrines provided a deeper understanding of the circumstances under which these works were produced.

The exhibition complicated the picture of art produced under authoritarianism by showing the dance between artists and the government under which they lived, highlighting the artists’ questioning of whether and how the state they lived in did or did not live up to its ideals. In the second gallery, the curators included a reproduction and translation of the “Ten Commandments for the New Socialist People” which were announced by Walter Ulbricht, then First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), at the fifth SED Party Congress in 1958. The commandments showcase the ethical ideals that accompanied the GDR’s foundation, giving insight for US audiences into the socio-cultural milieu in which the artists in the exhibition grew up and worked. A strong ethic of collective work and solidarity are exemplified in directives such as “Number 5. You should act in the spirit of mutual help and comradely cooperation in building socialism, respect the collective and take its criticism to heart.” The artworks included in this exhibition demonstrate how the GDR’s socialization of its citizens toward the collective rather than the individual took form in ways the government didn’t anticipate.

Installation view of Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany, room 3. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art.

The “Ten Commandments” are paired with a document from near the GDR’s end: “Für unser Land” (“For Our Country”), an open letter drafted by a group of 31 East Germans, edited by writer Christa Wolf, and read aloud by author Stefan Heym at a demonstration on November 28, 1989. The letter pleaded for the retention of a separate East German state committed to socialist ideals, and eventually collected one million signatures from citizens who were in support of it. The inclusion of the letter is critical to understanding that many East Germans wanted a reformed, democratic, Socialist GDR, not its unification with West Germany. They embraced the sense of social justice under which the state was founded and envisioned a future in which it was fully realized.

Collaboration as an artistic process was the theme of the show’s third and final gallery. This room was the most dynamic of the exhibition as the arrangement of the works and diversity of their styles brought them into a stronger conversation with each other than happened in the previous galleries. Shown here were a broad range of approaches: artistic collaboration in the Silberblick I Portfolio (1989) of portraits; artists collaborating with subjects in the Alt Sein / Tamerlanseries (1979–1987) by Gundula Schulze Eldowy and Gedankensplitter (Slivers of Thought, 1984) by Gabriele Stötzer; and artists collaborating—though not in the usual sense—with Ministry for State Security (the Stasi) in Bis auf weitere gute Zusammenarbeit, Nr. 7284/85 (Until Further Useful Collaboration, Nr. 7284/85, 1992–93) by Cornelia Schleime. The juxtaposition of Schulze Eldowy, Stötzer, and Schleime was particularly striking. All worked with photographic portraiture and female subjects. Schulze Eldowy works in a traditional social documentary approach, photographing her neighbor Tamerlan (Elsbeth Kördel) over eight years as she aged and coped with debilitating illnesses. With this genre of work, the viewer never knows how much control the subject has over their self-presentation, though the ongoing nature of this interaction gives a sense of Tamerlan as an empowered subject. Gedankensplitter by Stötzer also consists of photographic portraits of women, primarily friends and artistic collaborators. In a series of photos of each subject that the artist presents on the oversized pages of an artist’s book, the models play with poses and props, exploring the body and their own self-presentation in a manner reminiscent of feminist artists like Mary Beth Edelson, though less spiritual and more materialist. Again, the viewer was reminded of the power dynamic between photographer and subject, although the inclusion of multiple images of each model in the pages also gives them more of a voice. Schleime makes the question of collaboration and of who controls what is seen the focus of her work. Produced after former GDR citizens gained access to the surveillance data kept by the Stasi, Bis auf… uses the reports of unofficial informants as the basis for a series of staged and humorous color photographic portraits, presented here as a looped series of projected images. The portraits are mounted on copies of the reports that inspired them, sometimes obscuring the text. Schleime also makes additional redactions to the text, limiting what the viewer can read. Through these actions, she reasserts her agency as a subject of surveillance, having the last word on how she is being documented.

Stötzer, Gabi. Gedankensplitter, 1984 and Abwicklung, 1983. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art. Photograph by Charles Walbridge.

Schulze Eldowy, Gundala. Alt Sein / Tamerlan, 1979-1987. Gelatin Silver Prints. Image courtesy of the Tweed Museum of Art. Photograph by Charles Walbridge.

The title of the exhibition—Anti-Social Art: Experimental Practices in Late East Germany—makes explicit a fundamental irony in the artists’ approach to collectivity. While the GDR bureaucracy was concerned with activities that might threaten “real-existing socialism” and was prone to labelling such artwork as “anti-social,” GDR art was very much inspired by the collective ethos that the GDR government was seeking to instill in its citizens. The concept of the “niche society” that is often used in relation to the (late) GDR implies a kind of withdrawal from public life into isolated “niches,” yet in this exhibition we saw that such niches were also home to counterpublics that would, in time, became important forces in the political changes leading up to 1989.

This last section also brought to the fore the work of women artists. As was the case in the “West,” women artists in the GDR often experienced marginalization in the visual arts, despite ostensibly having equal access to education and career opportunities. Projects like the Silberblick I Portfolio, curated by Gabriele Muschter and Hildrud Ebert, where seven pairs of women artists responded to each other’s work, parallel similar actions by feminist artists in other parts of the world who interrogated the myth of the lone artistic genius. This points to a certain tension in the position of the artist within GDR society. On the one hand, there was a continuation of the Romantic idea of the artist as a special individual who stands apart from society. On the other hand, there was the cultural emphasis on the collective that manifested itself on many levels, including the state-initiated project Bitterfeld Weg (Bitterfeld Path) in which artists were embedded in factories in the industrial town of Bitterfeld as part of a sort of proto-social practice project from 1959–1964. The failure of this state-initiated project was addressed by the collective work Bitterfeld 4400, organized by the curator Eugen Blume and featuring sixteen artists including Tina Bara, Peter Theime, and Robert Rehfeldt. The artists revisited the town of Bitterfeld and the toxic environmental legacy of its chemical industries as a symbol of the failure of state socialism to deliver on its promises.

In place of a traditional catalog, the exhibition is accompanied by a self-produced publication inspired by the informal publications produced by artists and activists in East Germany. The free takeaway features a series of short essays by the two curators, as well as GDR scholars Seth Howe and Briana Smith, with artwork by Olivia Cordray. Rather than a strictly academic take, these writings weave the authors’ personal experiences and responses into their research. As such, they help establish a link between the past and the present, shedding light on the researchers’ fascination with the GDR, and suggesting why it might become our own.

In Anti-Social Art, we saw artists navigate the two extremes of complicity and resistance within a society of super-surveillance and authoritarian structures, trying to finding gaps in the system that would allow them to create pre-figurative utopias and spaces for action. Group exhibitions delimited by geography and time period such as this one often have a somewhat paradoxical goal: conveying what is remarkable about a particular configuration of artists working in a certain place and time, while also demonstrating the relevance this work holds for current audiences. My experience has been that the US-American imagination is not always ready to see similarities between the GDR and US, but for those of us who have been active in alternative scenes—particularly in the 1970s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s—seeing parallels and divergences is unavoidable, even where such parallels are not explicitly addressed in the show. For instance, the challenging, body-based work of the Auto-perforation Artists (a Dresden-based group of performance artists including Michael Brendel, Else Gabriel, and Rainer Görß) brings to mind US performance artists like Karen Finley or Bob Flanagan, who were similarly creating work in reaction to regressive politics and who explored the limits of the body. Less spectacular, but no less important, were the activities of groups such as Clara Mosch (Carlfriedrich Claus, Michael Morgner, Thomas Ranft, Dagmar Ranft-Schinke, and Gregor-Torsten Schade) whose gallery space was sanctioned and supported financially by the state; however, this support required compromising their vision about the kind of work exhibited, and this eventually led the collective’s decision to close the gallery in 1982. This mirrors the experience of many artist-run spaces in the US that are faced with a choice between economic security or compromising their vision, though in these cases it is in response to the demands of the market rather than the state.

With its focus on alternative art scenes in the GDR, Anti-Social Art gave US audiences a welcome look into a world that at first may seem very distant, but that in fact has much that is timely and relevant. The exhibition required serious effort from its viewers; the quantity of artwork and expository information could be overwhelming, even for someone with some background knowledge of the East German artworld. The exhibition took a sober look at the conditions of production for GDR artists, successfully avoiding the romanticization of their activities, while also shedding light on what we can learn from them. In this way, the artists represented in the show and their work provided models of what it means to live an ethical life under repression, by finding the gaps and creating alternatives within them.