Entangled Roots in the Mutating Nature of the New East: Kristaps Ancāns in Conversation with Corina Apostol and Jasmina Tumbas

Romanian-American-Baltic curator Corina L. Apostol and Latvian-British artist Kristaps Ancāns have recently begun a series of collaborations that focus on expanding discourses in contemporary art to include transnational perspectives centered on the New East. In December 2021, Apostol served as the curator for Ancāns’s large-scale site-specific installation what can’t we just create (2021-2022) at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils, Latvia. Prompted by the current invasion of Ukraine, Apostol and Ancāns revisit this installation in conversation with art historian Jasmina Tumbas, to discuss how they—as cultural workers from the region—negotiate the reconfiguration of questions of identity, nationalism, and sexuality during this crisis in Europe.

Jasmina Tumbas: what can’t we just create is installed at a site where the architecture itself is burdened with histories of political change and warfare. Why do you think this particular work helps unfold some of the political complexities of this local context?

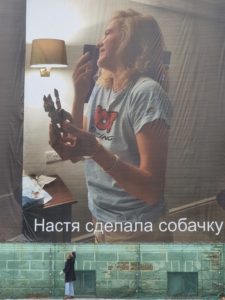

Corina Apostol: The context was crucial in unfolding Kristaps’ project, which was conceived in direct dialogue with it. He combined four monumental banners with a large-scale sculpture: one banner displays a poetic text in black font on white background (written in Latvian, Russian, and English), and three color banners combine photographic portraits of a young woman, Nastya, together with text in the same three languages. Finally, there is a sculptural piece: a lone palm tree.

I thought it was very important that Kristaps decided not to place an artwork within the Mark Rothko Center itself. Rather, the project unfolds a few buildings behind it, in an area framed by Soviet-era blocks where people still live today, and a large police station in an Empire-era building: literally a clash of ideologies embodied in architecture. The site once sheltered air pilots and war machinery; it carries a history of conflict and traumas, of national self-determination. Now it is being actively built up into a dynamic cultural and educational hub for the region of Latgale, in south-eastern Latvia. The community around the Center is for me representative of the New East, in the sense of promotion of public participation, new educational approaches, and potential for growth of the Post-Soviet region.

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

Kristaps Ancāns: I found this particular site quite fascinating. The fortress itself was built swiftly between 1831 and 1833 by Russian Emperor Nikolay I, in fear of Napoleon invading, and afterwards, it was continually used for military purposes. Inside its gates, there are cannons from different eras still standing, bringing a strong connection with the army, and suggesting imminent destruction or fear of it. On the other hand, the green mesh covering this building suggests that we can construct something there, or the evolution of something, a potential: We don’t need revolutions anymore. Let’s build and go on. In this location that has been created with a serious potential to destroy or to be destroyed, I found an amazing site to have a conversation about creation.

JT: The green mesh is striking, and so is what we see beneath it, as well as parts of the building that remain untouched by the net. The conditions of the site conjure up different temporalities, again, reminding us of the tension between “East” and “West.”

Current discourses around the invasion of Ukraine have brought to the surface familiar and tired Cold War rhetorics, while they have also inspired us to think about new possibilities for solidarity. In this regard, I wanted to ask you, Corina, how this installation might speak to what some deem the imminent destabilization of Europe or potential for solidarity? What role do you think art, especially when displayed in the public, plays in shaping and making possible new narratives?

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

CA: The project was completed right before the war began, and of course, now it brings new associations with the conflict unfolding at our borders, as the definitions and borders of Europe are again shifting.

Kristaps looks at the mechanisms of three languages, each with its own cultural heritage spoken in Latvia, and how they interact with each other. On the textual banner, these languages are connected in a pointed yet open-ended symmetry, asking: who are the cultural insiders and who are those on the periphery? Living in Tallinn, I was struck by how the Russian-speaking community is segregated from the Estonian one. There’s a very strong distinction made between them in social, cultural, and political processes. While this separation is not so pronounced in Latvia, now there are renewed antagonisms, conflicts, and cultural tensions as a result of the nearby conflict. Nonetheless, as Kristaps’ project suggests, we are all living in this space together and have to find ways to coexist.

As this project demonstrates, working in public space is always political, either in support of or against something. There is no illusion of neutrality at present. More and more people in the East are occupying public space, intervening at the nexus of art and activism to bring attention to the war and support for people in Ukraine. And even if they are in the minority, activists in Russia today are also protesting and risking being jailed for 15 years for denouncing the war.

JT: Central to what can’t we just create are three monumental images of Nastya, a young woman wearing a T-shirt, installed on large banners on the exterior walls. Seeing her in short sleeves in this environment with snow, in the extremely cold weather, creates a sense of discomfort. What role does this photography play in your practice?

KA: The images created were not staged photographs. I use photography to capture surprising moments, when something interesting happens, or when the true emotion of the person shows through. You can’t stage this kind of moment. I decided to use these images, and transform them, to artificially pump them up in this extreme environment. I had made them before I had any idea for the project in Daugavpils and stored them in my archive as material.

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

JT: What role does gender play in this triptych-like installation, which shows a female-identified body captured in an intimate moment of joy, holding a toy? How do you think it might participate in the long and much-critiqued history of showing the female body in art?

KA: The context of the site gave added meanings to the photos rather than photos changing the site. For me, this context is the main tool that transforms and mutates anything that comes into it. Nastya (short for Anastasya) is a close friend of mine. In Russian, using the short form of her name already shows that she is a friend. The moment that I captured, an instant of happiness after a very long hike together, is not staged. I bought a Kinder Surprise because I thought that it is funny that in childhood we collect the small toy sculptures inside. The moment when Nastya puts together the toy is about seeing the result of your actions. Nowadays, when we work, a lot of what we do remains digital or immaterial. It is saved on servers, and oftentimes we don’t see the actual or direct result of our actions

JT: Whose actions? I am thinking here about the extensive history of stereotypical depictions of women that haunt the three photographs of Nastya in your installation, conjuring images of East European women as beautiful, childlike, and naive, as well as reductive representations of young women as sex workers or mail-order brides, in need of a savior from the West.

KA: Any of your actions that you can see the result of.

Nastya is a popular name, even outside the Russian-speaking community in the Baltics, in East Europe. In the 1990s and 2000s, stereotypical qualities associated with women from the Baltics were created. In the film “Buy Bye Beauty” (2001), Pål Anders Jörgen Hollender claimed that 40 per cent of women in Riga were sex workers, that the East is so poor that you can do whatever you like here. Later he admitted that the movie had been staged and presented false information. As an artist from the East, provocations are stereotypically expected of us. We keep hearing the expression “catching up with the West ” but here Hollender wanted to “catch up with the East,” hoping that the combination between flat provocations and false information could turn something into artwork. These patriarchal stereotypes have been very damaging to the Swedish image in the Baltics.

As a queer man, when I was taking these photos and later installing the banners I wasn’t thinking about stereotypical depictions of the female body. Nastya is herself Ukrainian, she holds a high post in Finance in London. She embodies a strong businesswoman persona. Right now, she is helping raise funds and help charities in support of Ukraine. I believe these stereotypes don’t haunt East Europeans so much anymore as we are focused on what the East can offer us and what we can offer to it. We don’t see ourselves as victims anymore, as we have matured. This awareness really outlines the essence of the New East to me.

JT: I’m interested in the link to the political dimension of conceptual art and its possibility for critique in the public, which historically emerged during the Cold War era and is commonly considered through the American and English-speaking art contexts. During the Yugoslav wars, artist Mladen Stilinović was already thinking through how the English language held a new type of supremacy in the post-1989 “global art” sphere, with his 1992 work An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist. Kristaps, your installation deliberately plays with questions of translation, as it uses English, Latvian, and Russian. Could you speak a bit more about the politics behind your conceptual framing for the use of language in what can’t we just create?

KA: Latvian, Russian, and English are three languages that I use daily. None of them is from the same language tree, but they are very present in cultural and political life in Latvia. Latvian is very poetic, and it is very difficult for me to discuss my works in this language. English is very technical and neutral to me. Russian is very expressive and has a very wide emotional spectrum.

For me, the usage of these languages in the project is about analyzing their construct mechanisms and how the linguistic system works. In a sense, I refer to conceptual art, but I am more interested in what the same sentence will deliver, and what kind of palette tones of the spectrum would appear. How do these three models of thinking meet? How do they interact between themselves, and how might they interact with or form certain thinking processes?

In English, “what can’t we just create?” has a lightness to it, a positive rhythm encouraging us to go on, to make something. In Russian, “что только мы не можем сделать” has a negative form almost until the end: можем сделать, or we can create, it is possible. In Latvian, it sounds like a chaotic mess. It stays on neutral negativity, because of the language structure. It opens the question: can we make it or can’t we make it?

Recently, tens of thousands of people took to the streets in Riga in solidarity with Ukraine. There hasn’t been activism on this scale in some time. This reminds me of the end of the Soviet Union, when during the Baltic Way, almost 2 million people from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania held their hands to create a chain. It was one of the biggest examples of activism in the world, and I feel that it is now returning.

JT: The fallen palm tree in what can’t we just create generates an interesting tension by inverting the usually erect image of a tree into this horizontal sculpture, which reads as a deliberate, anticlimactic gesture, especially resting on the cold snow. Multiple inversions of expectations seem to be at play here, the palm tree also connoting a different climate in the harshness of the snow. When I first looked at the installation from afar, the palm tree appeared like a sculptural bench, perhaps a contextual assumption because the Rothko Center summons the idea of the viewer immersing themselves in a contemplative relationship to art. But once a viewer approaches the palm tree, it’s a cold and uncomfortable object: exposed, metal screws keep the sculpture together and the texture of the tree is made by chainsaw cuts all over the wood, with sharp edges everywhere, upending any fantasy of a warm holiday and instead of leaving us with an uninviting work. Historically, queer art often plays with these types of inversions. Could you elaborate on why and how the position of the palm tree is central to this installation?

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

KA: I began thinking about palm trees as an alien form when I moved to the UK in 2014. I observed them planted next to birches in the same garden. For me, this combination of a Nordic tree next to a tropical one was unusual, even uncomfortable. In this work, a different context is introduced into the project through the sculpture of the palm. I chose that specific site because I was fascinated by two linden trees growing in that field which weren’t purposely planted there. We can see that species from the East can root in the West, but it doesn’t follow that plants from the West are able to survive the climate of the East.

At the inception of the project, I worked with textual banners on the building, and then I imagined how to find a relationship with the linden trees. The palm tree was the last element to come in. I wanted to make the sculpture with my own hands, as opposed to something mechanically produced, like the banners. I carved it out of a single Aspen tree (native to Latgale), using traditional techniques on how to split the different wooden parts.

I wanted to create something that can’t take root in that environment. We can carve and make many things from native trees, but it is an object that can become a piece of furniture or a decoration—it can’t grow roots. Through this metaphor, I am looking at how that region’s society needs to adjust to something alien that comes in.

JT: When we started talking about the war in Ukraine, you commented on the privilege of having gained this new gift of freedom from the Soviet Union in Latvia in the 1990s, and how there was pressure to build a new society. The current war in Ukraine invokes many fears attached to losing that freedom. Considering this acute context, I cannot help but look at the palm tree as an object that appears almost corpse-like, a dead tree, connoting a desolate political landscape and its victims. This political reading is intensified by the fact that while it is made from local wood, its form emulates something that doesn’t or cannot hold roots in that very local context.

KA: The Soviet Union came to an end and transformations started happening right away, and then in the 1990s different values and perspectives emerged. You don’t even have time to think about how to adapt, how your society will adjust in 30 years. Directly comparing a society to these trees can sound stereotypical. At the same time, I am cognizant of the difficult process my parents’ generation went through as they switched from one system to another. It’s a harsh process, similar to transporting a palm tree from the South to the North. Coming from a place where you weren’t allowed to discuss the political system, you then had to become an active citizen when the Barricades (1991). and the events of the Singing Revolution (1986-1991) happened. You needed to adopt a position.

JT: Apart from your collaboration for the large-scale project at the Rothko Centre, what can’t we just create, you have been working together on multiple projects in addition to holding teaching positions at the Art Academy of Latvia. You also both share a background of coming from the former East, albeit from different contexts, and actively participate in contemporary dialogues about what many now refer to as the “New East.” As someone with roots in the former Yugoslavia, I am interested to know how your position towards the “old” and “new” East(s) manifests itself in your work?

KA: That work discusses the communities and the relationship between cultures inside the New East and its emerging relationship with the West. I was just one year old when the Soviet Union collapsed. Luckily in the Baltics, the revolution did not turn into a war. However, there’s a déjà vu feeling haunting people in Latvia at the moment, a strange mental bubble that everything is repeating itself, which generates mental numbness. There is fear and anger that all that has been built and rebuilt can be ruined again.

Destructive decisions are being made by a succession of weak, untalented leaders who lack the knowledge of leading a country without killing and violence. While the world is thinking about going to the Moon or to Mars, they are threatening us with nuclear weapons and bombing children’s hospitals in Ukraine. At the moment, there is a very disquieting feeling that the Russian war can shatter the relationships between communities.

While for some in the West, growing up in a newly started world may seem like a romantic notion, here in the East–being a buffer zone for the colonizing powers–we have experienced an almost non-stop state of instability. How to restart the world? How to create a new world on the ruins of the old one? How are we mentally prepared to survive under these conditions? The New Eastern communities have gone through this restart, while still being surrounded by the ruins and footprints of the old world (with a different heritage and different reference points), and while they were trying to find truth in systems and structures even if the findings disappointed them. However, this process has produced interesting experiments, mutations and discoveries regarding both the New East and the heritage of the Old East.

I grew up with the idea that you need to build, create, and construct, that you have the privilege to question things. Still, our society continues to learn how to approach democracy, and what democracy really means. The study process is interesting because the East is able to teach the West some lessons in democracy.

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

JT: Corina, you have a different access point to the New East, having experienced a few more years under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s system in Romania, before the changes in 1989, and then also having spent many years in the United States before returning to Europe. Could you speak to this question of building one’s identity around the nation?

CA: I was born in 1984 when Romania was under the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. My grandparents were educated in Moscow during late Stalinism and spoke fluent Russian. My parents came to maturity during the consolidation of the nationalist dictatorship in Romania that emphasized Romania’s Latin and Dacian heritage, and its alliance with the West. Their generation rejected the Russian language and culture. The late 1970s and ‘80s were characterized by harsh repression, while the dictator was building up a megalomaniac Palace inspired by North Korean architecture. I then witnessed the civil war that ensued his demise in the 1990s, when Romanians fought for the freedom to create a new world, instead of going back to the old system, while the ex-cronies of the dictator tried to hold on to power.

I was later educated in the United States, looking from the outside at the non-conformist artistic practices in the 1970s and ‘80s. The distance from my native context has given me a critical lens to understand my culture within the larger geopolitical processes of the Soviet Union as it disintegrated, and then the consolidation of the new European Union. The distortions and manipulations of recent history in Romanian textbooks drove me and my colleagues to re-educate ourselves about what this legacy means and why it matters beyond our region, as a shared East-West history.

Since I started working at the Tallinn Art Hall and more recently in the POST program at the Latvian Art Academy, I have engaged with communities where I am making a difference. Kristaps and I have a critical attitude towards nationalism and conservativism in the Baltics, the direction the development of the infrastructure for art and culture is taking, and the Western paradigms that we were educated in. Currently, we are building projects and educational programs that respond to the local context at this very challenging moment, when the East-West conflicts begin to re-emerge and re-shape the legacy of the last 30 years.

JT: Corina, you describe Kristaps as an “explorer.” As the curator of the Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2022), you also critically engage with histories of “exploring” and “discovering,” and the legacy of colonialism in Estonia. This connection between your work on the Pavillion and what we can’t just create is most obvious, formally, in the palm tree sculpture that references the exotic element in Kristaps’ installation. Could you unpack some of these thematic entanglements for us?

Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create, 2021-2022. Site-specific installation, Mark Rothko Art Center, Daugavpils, Latvia. Photograph courtesy of the artist and curator.

CA: The parallel with “exploring” is very interesting. In my work for this year’s Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, I am dealing with the biography of Emilie Rosalie Saal, a botanical artist born in late 19th-century Estonia who became an “orchid hunter” in Netherlands-colonized Indonesia in the early 20th century. Kristaps served as my curatorial advisor, and we discussed at length the legacies of Eastern Europe’s “colonialism without colonies”, recent postcolonial and decolonial debates in our region, and how they fit into the larger framework of the colonial project in the West. We also considered some of the strategies for understanding the differences and similarities between East and West when it comes to the consequences of colonialism(s).

I share with Kristaps the analytical approach to this context, researching its multiple layers, and seeing the reception of an artwork as being situated in a specific site, which also becomes part of the project. In the process of curating what can’t we just create I discovered the Latgale region and its communities and also Kristaps’ approach to this context as he revisits his birth region and draws attention to language and culture conflicts, and also to the sense of alienation and foreignness that these elicit.

KA: I see a lot of parallels in our approaches, as Corina has been educated and worked in the US and decided to come back to live in the New East, while I had a similar experience returning from the UK. Both of us use these different contexts and analyze what they mean. I believe that the time of contemporary art has ended, and that we live in a “contextual art” age, in the sense that we know more about ourselves, and about the Other. Corina and I use context as a medium in itself, and as a form and analyze what this duality expresses in situ. Moving a work from one place to another, or even moving the material from one country to another, creates the form and its reception. I think that’s why we found common ground for our collaboration. We are both excited by the exploration of these contexts in relation to what they create.