The Story of the Ukrainian Pavilion in Venice and Exhibition-Making as a Matter of Cultural Survival: An Interview with Maria Lanko

With the upcoming 59th International Art Exhibition in Venice on April 23, Maria Lanko, Lizaveta German, and Borys Filonenko—the curators of artist Pavlo Makov’s project Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta for the Ukrainian Pavilion—have found themselves in a difficult situation that has made it impossible for them to continue working on the exhibition. On March 8, 2022, the organizers of the pavilion announced that “despite the ongoing war, the team managed to evacuate the fragments of [Makov’s] artwork from Kyiv” and will be able to present it at the upcoming Venice Biennale.(1) However, evacuating artworks and organizing an exhibition during times of war takes enormous strength. Since February 24, when Russia invaded Ukraine, hundreds of thousands have fled the country and those who have stayed are building up a strong resistance. Both actions require a great deal of determination and belief in a better future. The war has affected everyone in the country, including cultural producers, artists, and curators, while also impacting the survival and presentation of Ukrainian culture itself.

With all international flights in and out of Ukraine cancelled and traveling around the country being so dangerous, curator Maria Lanko risked her life by driving for days to bring the artworks out of Kyiv with the hope of eventually transporting them to Venice. Denisa Tomkova spoke with Maria about the situation in Ukraine, the impact it has had on the biennale team, what the international art community can do to support them and why exhibiting art still matters even in times of war.

Denisa Tomkova: First of all, how are you? Are you safe?

Maria Lanko: I am good. I managed to leave Kyiv on the first day of the invasion and I am now pretty safe and comfortable in my friend’s house in Pavshyno, in the Zakarpattya region—just about 30 km away from the EU border. However, my family and friends are not safe—most are staying in their houses in Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Chernihiv under non-stop air strikes.

DT: The planned Ukrainian Pavilion exhibition was to present work by Ukrainian artist Pavlo Makov. Can you tell me more about the exhibition concept?

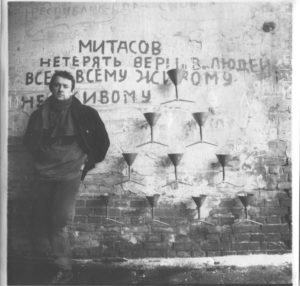

Pavlo Makov by The Fountain of Exhaustion mounted on the Oleh Mitasov’s house in Kharkiv, 1996. © Pavlo Makov. Courtesy of the artist.

ML: It’s hard to avoid editing our curatorial statement in the shadow of the Russian war on Ukraine, but I’ll try to minimise that influence as I really believe the work is significant in itself, regardless of its current context. It is called Fountain of Exhaustion, and basically it is a fountain made up of 105 identical bronze funnels arranged in a form of triangle on a wall. Each funnel has one “mouth” and two “spouts”, so the water in it splits in half. And the incoming stream of water from the top goes down the fountain gradually exhausting itself closer to the bottom. This piece was conceived by Pavlo Makov in 1995 in Kharkiv, inspired by the city’s landscape with its rivers drying out, as well as by the city’s ruined infrastructure—typical of the time—with constant water supply disruptions, neglected public spaces, and non-functional city fountains. Today I would say that it was a very poetic monument to the collapse of the empire and its inevitable consequences. The piece was never fully realised though: it was exhibited as a sculptural concept but was never a working fountain before. When applying for The National Pavilion competition in 2021 with my co-curators, we felt that today the fully-constructed fountain can have a larger meaning internationally (and here I quote our statement from months ago) — “reflecting depletion of earth’s resources, post-pandemic burnout, social media fatigue, and exhaustion by wars”. It is scary to read those lines today. But also not surprising as the empire had to try to strike back, didn’t it?

DT: The work truly is allegorical. You once commented on the fact that this project was never fully realized as intended, stating that it “is symptomatic for Ukrainian art, whose history is not only about what happened, but also about what has not happened, has not been properly represented.”(2) It would be a real shame if the project couldn’t be realized this year either…

ML: Oh indeed. In Ukraine we often see that art works as self-fulfilling prophecy. But looking at how Ukraine is reinventing itself in real time in the face of war, I truly believe that we’ll be able to break this logic of being unrealized and unrepresented. The Pavilion simply must keep up with the country’s present subjectivity and presence. We are very much determined to do that.

DT: Where are the other members of the curatorial team and the artist at the moment? How are they coping with the situation?

Borys Filonenko in Kryvorivnia, on the way to Verkhovyna, Ivano Frankivsk, and Lviv. Courtesy of Borys Filonenko’s personal archive.

ML: Like me, Borys Filonenko is in western Ukraine, but he is mostly occupied with humanitarian tasks to support his family staying in Kharkiv. Liza German is in Kyiv with her baby due in about a week, yet she is very strong and energetic—I keep calling her to get an attitude boost. Pavlo Makov, together with his wife, is staying in Kharkiv and sheltering non-stop. His mother is 96 years old but she refuses to go down, and spends the days in her apartment.

DT: How did the Russian invasion of Ukraine affect your preparations for the Venice Biennale?

ML: It affected our lives dramatically. As of the sixth day of the war the biennale team was either taking shelter in basements or trying to move to a safer place. It took me six days to reach the location where I’m at now, when normally the trip can be done overnight. But I should not complain: many people are staying this whole time in the cold, underground and without much food or comfort. Our work is almost entirely disrupted as we’ve been busy saving our lives. The only thing we were able to do is to communicate with journalists, but mostly by virtue of our communication manager Katya Pavlevych, who lives in New York.

Curator Liza German’s room. Courtesy of Liza German’s personal archive.

DT: Since the attacks also hit the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, you have been moving the art pieces for the Venice Biennale out of the city by car, to a secure place. You already mentioned it took you six days; can you tell me more about it?

ML: I took off in the late evening on February 24: the roads out of Kyiv were jammed during the whole day, so as soon as I saw on Google Maps that one of the roads was becoming “red” after being “black” for ten hours, I got on it. It wasn’t exactly the necessary direction, but who cares. My route was Kyiv — Hrebinky — Khmelnytsky — Yaremche — Mukachevo — Pavshyno with every leg taking five times longer than usual. Now I am waiting for a “green corridor” for the whole team on the border: our male members are not allowed to leave because of martial law.

DT: It must have been very exhausting to drive for six days non-stop. Were you driving on your own? How did you cope with tiredness?

ML: I guess our bodies are operating in a special regime at the moment: I only felt signs of fatigue the day I didn’t need to drive anymore. I also had two companions with me: a friend and a dog, which made the journey bearable.

The evacuation car. The window is covered by a box (from one of the pieces of the Fountain) and taped shut. Courtesy of Maria Lanko’s personal archive.

DT: You have been driving towards the west of Ukraine with the hope of eventually transporting the artworks to Venice. What are your next plans? And which challenges are you still facing with preparations for the exhibition in your current circumstances?

ML: The biggest challenge is the exhaustion in the face of war. Following the numbers of dead and injured civilians, looking at the images of destroyed Kharkiv, and hearing voices of friends in fear makes the whole business of the Pavilion somewhat irrelevant. But of course, we try to keep our spirits up by remembering that culture is as essential to stopping the war as defence units.

My next steps are to find a workshop in the EU that can produce the Fountain of Exhaustion as it was designed by our architectural partner, ФОРМА. Working on these practical tasks will hopefully allow me to stay sane.

DT: As the organizers of the Ukrainian Pavilion, you have published a statement against the presence of the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Can you please tell me more about your position?

ML: Our position on the Russian presence at the Venice Biennale is unequivocal: Russia must be disconnected from cultural events, as well as from SWIFT. We are now witnessing major festivals and institutions gradually daring to call a war a war, instead of referring to it as a kind of “situation” or a “tragic event.” However, this process is slow. In our statement, we emphasize that Russia has violated all the principles of dialogue and instead of words it has used real weapons that are destroying Ukrainian cities today —Kyiv and Kharkiv, in particular. These bombs are falling on monuments of constructivist art, on works by the naive artist Maria Pryimachenko, and on the aircraft An-225 Mriya, which was part of the Open Group project at the 58th Venice Biennale. Therefore, remarks about the festival as “a place for dialogue” despite the war are not appropriate.

DT: How can the international art community support you and other Ukrainian cultural producers at the moment?

ML: We want the project Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta to open in the pavilion of Ukraine on April 23. To do this, we need assistance in the production of objects and architecture, as well as with the printing of the catalogue.

In addition to the Ukrainian pavilion, there are several other important issues: the fate of the Russian pavilion and the presence of Ukrainian art in the international media. What should the pavilion of Russia look like? Empty, paused, or decolonized? This issue should be addressed in the international dialogue about cultural appropriation and imperial cultural politics.

It is important to cover the events in Ukraine, taking into account what kind of art and culture the world is losing with each artillery shelling. It is now extremely important that there be deeper representation of Ukrainian art, names, works, and the events that make Ukraine an important part of Europe.

Photo: Lizaveta German, Borys Filonenko, Pavlo Makov, and Maria Lanko. Photo by Yevgen Nikiforov.

DT: Some artists and cultural institutions have been cancelling their exhibitions in solidarity with Ukraine. What would you say to those who argue that in such catastrophic circumstances, art is not as important as saving lives and developing socially engaged civic strategies? Why, in your opinion, does it matter to still produce art and exhibitions, even in times such as this?

ML: Exhibitions are proliferating, mostly in the West, and I truly support those who decide to cancel their shows for a direct action. But the Ukrainian art scene is unseen and unknown, so for us making exhibitions is a matter of cultural survival.

This interview was initially begun in late February 2022. As of the time of publication, on March 15, curator Maria Lanko has just reached Italy, where she will continue her work on preparations for the Ukrainian pavilion at the Venice Biennial. Curator Borys Filonenko also contributed to the answers in the interview.

Those who wish to donate to support the Ukrainian art community can do so through the Ukrainian Art Emergency Fund. Any contribution is helpful.

This interview is the first in a series of posts at ARTMargins Online that will address Russia’s war on Ukraine, the Ukrainian cultural scene, and the Ukrainian Pavilion.

FOOTNOTES

- “Ukrainian pavilion will make it to La Biennale despite the ongoing war,” press release, https://docs.google.com/document/d/15ZLQ7TuNuFB9jg8Njgwz9-KyWc6i_c9CRQNpxxfOP9Y. [back]

- Artur Korniienko, “Early Look at Ukraine’s Exhibit at Venice Art Biennale,” The Kyiv Independent, January 25, 2022,https://kyivindependent.com/culture/early-look-at-ukraines-exhibit-at-venice-art-biennale-exploration-of-worlds-exhaustion/. [back]