From Rags to Monuments: Ana Lupaş’s Humid Installation

How can we, in the middle of a heated debate around public monuments as highly visible and dominant bearers of history around the world, perceive the more layered and subtle aspects of commemorative practice? Reflection on anti-, counter- and performative monuments has not abated, but been absorbed in the current worldwide struggle to remove, replace, and otherwise neutralize monuments spatializing unjust power. That is all to the good, as long as we don’t forget that monuments, and artists, can do things that bear witness against impossible odds—and without erecting anything permanent. In this essay I look at several iterations of Romanian artist Ana Lupaş’s processual sculpture Humid Installation, first installed in the Grigorescu neighborhood of her hometown, Cluj, in 1966, and later and more iconically just outside the nearby village of Mărgău in 1970.(A text in the artist’s 2008 retrospective at the Taxispalais in Innsbruck, Austria, claims: “In 1970 Ana Lupaş created the first large Humid Installation in Mârgău village, Transylvania. Amplifying an older work she produced in the Grigorescu district of Cluj in 1966, this ephemeral installation was realized with the help of 100 inhabitants of the village.” Silvia Eblmayr and Alina Șerban in consultation with the artist. https://artmap.com/taxispalais/exhibition/ana-Lupaş-2008, accessed May 20, 2020. See also Ramona Novicoc, Ana Lupaş: Soliloquies (2019), https://institutulprezentului.ro/en/2019/11/15/ana-lupas-soliloquies/. Alina Șerban notes in her “Inseparable Histories: Process, Embodiment, and Preservation in Ana Lupaş’ Work,” in Daniel Grun, Subjective Histories. Self-historicisation as Artistic Practice in Central-East Europe. Bratislava (VEDA: SAS Publishing House, 2020), pp. 267-80, that the Cluj precursor was called Flying Carpet and thus belonged, at least partly, to another series of Lupaş’s works of the period (1966-70) concerned with the tension between textile materiality and transcendent experiences like flight.)

Ana Lupas, Humid Installation, 1970, two color photographs, each 40 x 61.5 cm (40 x 123 cm overall). Courtesy the artist and P420 gallery, Bologna. Photo: Carlo Favero.

The work, consisting of long parallel lines of wet linen hung to dry, did not commemorate any particular past event. Rather, as I will show, its collaborative production process – inextricably linked with both its material and mediation – established historical connections to rural life and women’s work, making Lupaş’s work a paradigm of critical commemoration, and a potent starting point for political re-enactments. Conceptual and sensuous at the same time, stubbornly intellectual and almost romantically folky, the Humid Installations need to be read in intimate and urgent dialogue with the historical changes, perhaps irrevocable, overtaking rural life and culture at the time. The abiding interest in this work, some fifty years ago and as much in the present and near future, inheres precisely in how it sets local, specific conditions not easily recovered in complex dialogue with other places and times. Lupaş revisited the installation as early as 1973 for the Young Artists Biennial in Paris, but perhaps its most fascinating recurrence came under a new name, the Rag Monument,(The curriculum vitae provided by Lupaş’s gallery P420 renders the name of the work Memorial of Cloth (Șerban, “Inseparable Histories,” p. 279), which can be taken as the official name; my rendering is more literally what the Roman title indicates (used or ragged “rags” rather than the neutral/new “cloth,” and the word monument). Characteristically, Lupaş seems to have staged a work by the same name in the Grigorescu District, Cluj, in 1985.) planted in front of the National Theater, across from Bucharest’s University Square, in 1991, to commemorate the unrests of the previous year.

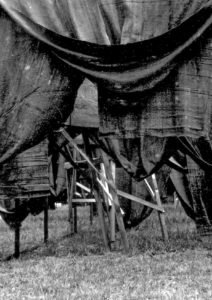

Ana Lupas, Rag Monument, Installation in front of National Theater in Bucharest, 1991. Courtesy the artist.

In June 1990, the recently and supposedly democratically elected government under Ion Iliescu, bussed in miners (possibly infiltrated by former secret police officers) from the Jiu Valley into Bucharest. These factions clashed violently with anti-government protesters, mostly students and liberal intellectuals, who protested the ruling National Salvation Front, comprised mostly of former communists.(See “Brought to Book in Bucharest: Romania’s ex-president, Ion Iliescu, goes to trial,” The Economist, May 3, 2018, online at https://www.economist.com/europe/2018/05/03/romanias-ex-president-ion-iliescu-goes-on-trial, accessed 9 August 2018. As of late 2021, the trial has not concluded, and is unlikely to do so, given Iliescu’s advanced age and delays caused by the pandemic. See also Dan Perjovschi’s work commenting on the unrests, Hysteria/Historia, 2009 part of Public Art Bucharest | Spaţiul Public Bucureşti, January 24 -February 13, 2009.) Given this dramatic change of scene from rural Transylvania to protest-torn Bucharest, a leading question, then, might be: how does the rural environment and the live process of making, as well as the photographic documentation and the recurrence of the form, sometimes in different materials, work to lend the Humid Installation historical specificity? And how was this specificity preserved, if it was, in a radically different spatial and political context? It is in what is preserved, and what changes, in mediation and reinstallation, that the work’s monumental characteristics emerge most saliently.

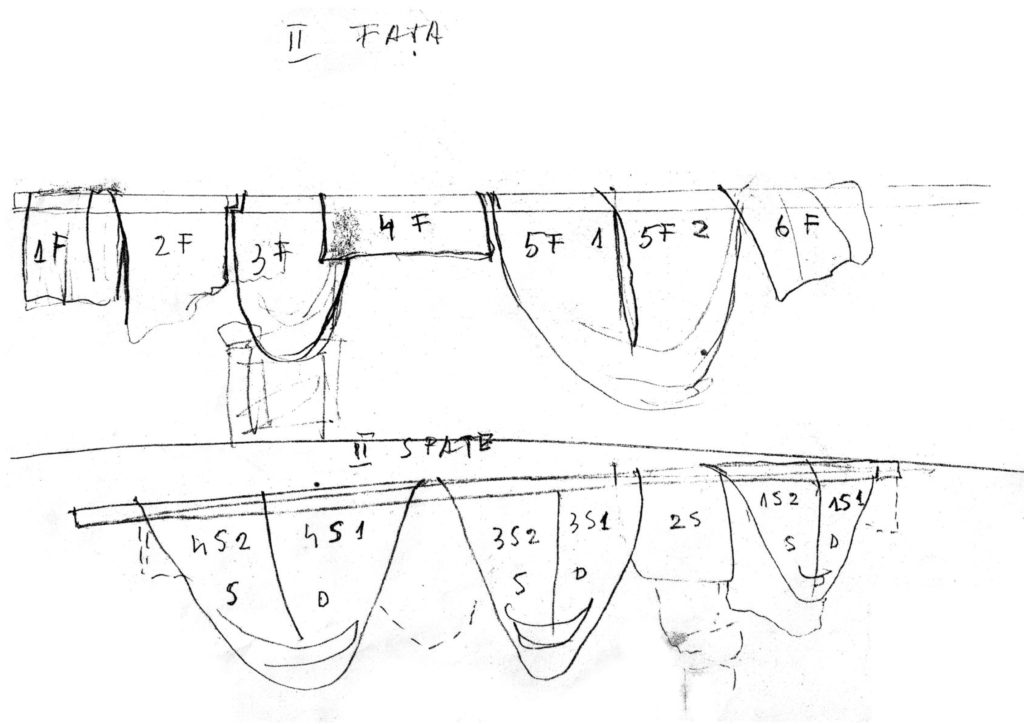

Ana Lupas, Monument of Cloth. Study for installation for University Square, Bucharest, Romania, 1991 (detail). Wood, tar, cloth; size variable. Courtesy the artist and P420 gallery, Bologna.

Humid Installation consisted first and most simply in designating an outdoor space for heavy, wet white linen to be hung to dry.(The Cluj 1966 Flying Carpet cloth was rhythmically punctuated by colored stripes.) At Mărgău, this was done with the voluntary participation of reportedly 100 villagers, mostly women, a considerable portion of whom are seen standing in the installation photographs, some still affixing the linen with clothespins to the twine strung from wooden poles. Three decades on in Bucharest, the related work Monument of Cloth was not hung wet but impregnated with heavy, dark bitumen or asphalt to stiffen the material while lending it a somber coloration and tactile presence, a configuration presented again at the St. Stephen Museum in Székesfehérvár, Hungary, in 1998. A metal version (the “cloth” cast in aluminum, the upright supports in stainless steel) was executed in 2013 and then shown in Dunkerque, on the French side of the English Channel, in a 2019-20 exhibition fittingly called Gigantisme.(See the exh. cat., Gigantisme—Art & Industrie (Dunkerque: au pole d’art contemporain de Dunkerque, 2019), pp. 8-9, and the text by Marina Lupaş, “Monument of Cloth” (2018), sent to the author via email on April 5, 2021.)

Ana Lupas, The Monument of Cloth, 1990, aluminum, 1.89 x 24.51 m. Installation view of exhibition Gigantisme: Art & Industry, Dunkerque Triennale, Frac Grand Large – Hauts-de France, 2019. Courtesy the artist and P420 gallery, Bologna. Photo: Gabriel Felezeu.

Given this lively afterlife and reception history, is the connection of Humid Installation to any specific place and historical matrix necessarily mediated through the person of the artist herself? Such a suggestion has its appeal: born in 1940 in multiethnic Cluj, and working there since, Lupaş’s activity as a teacher, arts administrator, sculptor, and artist in “applied” media (traditionally gendered female) has created a consistent, appealing voice advocating for connections between metropolis and province, between the local and the global in contemporary art. But indexing the work’s effect too closely to her personality might obscure how it inaugurates a commemorative practice, even and especially in her absence. Without neglecting the artist, we must attend to the material history of the work, both in the original serial rolls of cloth, and their later metal surrogates, and to its modes of making and reproduction, whether in monochrome and color photography or, more recently, in permanent museum installations. For all this historical expanse, the first iterations of the work prepare the monumental implications in the versions that follow. Those early iterations, in posing questions about peasant life and communist modernization, make novel commemorative claims of their own by tapping conceptually into the retrospective, preservationist discourse around folklore in Romania in the second half of the twentieth century.

In the critical literature, Humid Installation is often associated with the domestic activity of peasant women, plausibly enough given that we can see some of them on the 1970 hillside, as if attending to a monumental load of laundry hung to dry. More recently, Lupaş and several scholars have discussed what Maria Alina Asavei calls the “politics of textiles” in Ceauşescu’s Romania: Lupaş (and other artists) made textile art that could be read as popular while resisting the demands of official folk art.(Maria Alina Asavei, “The Politics of Textiles in the Romanian Contemporary Art Scene,” TEXTILE: Cloth and Culture, Vol.17, No.3 (2019), pp. 246-58. This topic extends beyond art as such into the lives of textile workers and the display of their work. See Alexandra Urdea, From Storeroom to Stage: Romanian Attire and the Politics of Folklore (New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2019), and Magdalena Buchczyk, “To Weave or Not to Weave: Vernacular Textiles and Historical Change in Romania,” TEXTILE: Cloth and Culture Vol.12, No.3 (2015), pp. 328-45.) Lupaş spoke of “process actions” already in the 1970s, much in the spirit of Western European and New York conceptual art. Another influential strand in Lupaş criticism, running from the 1970s into the present, situates her work amidst abstract concerns with symbolic systems, ritual, and folk cosmologies.(Anca Arghir, “Lupas, Ana,” in Contemporary Artists, ed. Colin Naylor and Genesis P-Orridge (London/New York: St. James Press/St. Martin’s Press, 1977), p. 576. The author states: “the conception was one of institutional rite, woven materials being spread out and hung over the landscape, in a solemn archetypal interpretation of working gestures, as it were, making up a message of manifold consonant rhythms, meant to integrate man, things and the natural environment.” See the artist’s own statement preceding, titled “The Meaning of My Work—Social Therapeutics,” p. 575. Compare Șerban, “Inseparable Histories” on “forms of social life that, due to their simplicity and essentialized character, interwove unexpectedly deep human and universal significances, and acquired a moral conduct,” p. 276.) What these apparently divergent observations have in common is an emphasis on the everyday as a site of meaning: in an early interview, the artist claimed that even at the risk of her works being destroyed, she preferred that they “be situated in places where people work and play…Places where…[they] are continuously touched in people’s everyday interaction with them.”(Ana Lupaş “În afara întrebării,” interviewed in the newspaper Munca, Friday, September 22, 1972, p. 24, cited in and translated by Izabel Galliera, Socially Engaged Art after Socialism. Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe (London: Tauris, 2017), p. 60. Munca (“work” in Romanian) was the organ of the Central Committee of Union of Romanian Syndicates.) There are certainly other process artists who favored ephemeral interactions. But the strange and powerful presence of Lupaş’s works in galleries, since the beginning, puts into question any convenient art historical lineage—land art, Fluxus, eccentric abstraction, or what we think of too casually as socially engaged art.(Olivia Nițiș has claimed Lupas as the first land artist worldwide in “Gender and Environment in Romanian Art before and after 1989,”Romanian Journal of Society and Politics, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2013), pp. 69-86. Nițiș also describes the later instances of Humid Installation as “re-enactments,” p. 73. Piotr Piotrowski, Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe (London: Reaktion, 2012), proposes a “horizontal art history” less beholden to Western terms.)

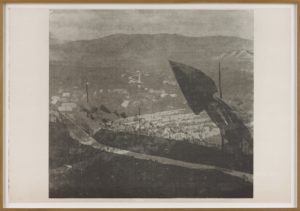

Ana Lupas, Humid Installation, 1970, photo printed on paper, 70 x100 cm. Courtesy the artist and P420 gallery, Bologna. Photo: Carlo Favero.

Humid Installation was first made at the high tide of communist modernization, and the field where the linen was hung to dry was officially owned collectively, though in reality, of course, it was state-owned. In Lupaș photographs, the hillside is shown panoramically from a higher vantage point, with some close-ups of windswept cloth; the artist even elegantly double-exposes or more precisely double-prints the two vantage points for simultaneous breadth of field and billowing detail. Here, we see the aesthetic complexity and collaborative nature of much traditional women’s work, but it is important to keep in mind that we also see practices and artifacts disappearing under the force of land collectivization. Could the initial project have been read as an imaginative restoration of pre-communist ways of peasant life, and what would it mean if that were the case? By the mid-1960s, the communist regime attempted to implement collective farming on the Soviet model across the country, in the process destroying peasant practices that in the early 1920s flowered in the wake of land reform, as Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman feudal systems collapsed throughout the former principalities.(On the Transylvanian background, see Irina Buzeanu, Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism. Nation Building and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995), pp. 129-88.) In the postwar period, a rhetoric of expropriating the expropriators was used to liquidate even small peasants in favor of work in the collectives. This left rural practitioners of material culture in a double bind much like that experienced by ambitious artists: maintain a crypto-resistance through memory or loudly affirm the past, fully aware of its new political uses?

The Country in the City

If Romanian postwar art isn’t what it initially seems in comparison to its Western European or American counterparts, neither are its sites. Site specificity in Eastern Europe always depended on spaces negotiated with and shored up against political authority, and that had to be imagined very flexibly, often built up belatedly in rumor, reception, and exchange. Thus, a vivid mail art practice and impromptu artist gatherings-cum-performances (most famously, Wanda Mihuleac’s house pARTy in late 1980s Bucharest) developed almost by necessity. But more generally, mediation (photographs, some video, drawings) became a solid part of site-specific practice, less as extensions of the site or its secondary documentation, than as primary vehicles to construct audiences and, ultimately, a public. Institutions were closely watched, and artists adopted various ways to fold these restrictions into their practice. “The site” was thus primarily one of imagining possible political and social content that audiences could only conceive, but not find in person.(This imaginative use of media makes contact, of course, with other East European artists: see, e.g., Matthew Jesse Jackson, The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), particularly chapter 4.)

For Humid Installation, the first clue to its site specificity lies in its tentative start, which was not in fact its appearance on a village green, but in a suburban apartment house courtyard. Mounted as Flying Carpet in Cluj in 1966, the installation may have served, as Maria Alina Asavei observes, to “symbolically purify this space.”(Maria-Alina Asavei, Rewriting the Canon of Visual Arts in Communist Romania: A Case Study, MA thesis, Central European University, Budapest (2007), p. 7.) But that is not all it did. Cluj is a medieval town and today the fourth biggest city in Romania with a third of a million inhabitants. Until World War II, Hungarians were in the majority, as they had been under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Hungarian uprising against Moscow in 1956 led to protests in Cluj as well, and these tensions no doubt contributed to the decision to reorganize the university and start a massive urban development program in the sixties, which manifested in the building of socialist apartment blocks, particularly in the Grigorescu district, north of downtown across the river Someşul Mic. Part of the aim was to settle more Romanians from the countryside there to participate in industrialization, which also shifted the demographic of the city (Hungarians are only 25% of the population today).(Yulia Oreshina, “Cluj-Napoca in communist Romania: anatomy of urban changes and memory,” in Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sectio F, Vol. LXVIII, 1-2, Lublin 2013, p. 145.) Such urbanism did not play out in a cultural vacuum. Being a suburb, Grigorescu also contained the open-air branch of The Ethnographic Museum of Transylvania, opened in 1929 in Romulus Vuiu Park, predating both the Village Museum in Bucharest and the Muzeul Astra (National Musum Complex ASTRA) just outside Sibiu. Thus, the separation of city and country, both in terms of work and culture, has fuzzy boundaries in Cluj.

Lupaş lived and continues to live in Cluj, which was important for modernization in yet another respect. As part of a general productive restructuring of the country, one of the aims was to identify villages that could be “promoted” to urban status, then developed and densified. In order to do this, research was necessary, and part of it happened in Cluj, designating key development areas, resettlement programs, and of course also those villages that were not of interest. Under Ceauşescu, this meant that villages had to fear falling outside development perimeters and being forced into abandonment for the sake of efficiency.(David Turnock “Planning of Romanian Rural Settlements,” The Geographical Journal, Vol. 157, No. 3 (Nov. 1991), pp. 251-64. Until 1974, the program allowed for enough ambiguities and adaptations that the local population could remain. In the late 1970s, rapid development and growing state control made rural living precarious.) Humid Installation’s affinity to a more organic grid of peasant “space and time” in the hills of Mărgău is just as much a response to semiurban living in Cartierul Grigorescu, where people from the country arrived to populate rows of apartment blocks.(An interesting recent assessment of Romanian art at the time is Alexandra Titu, “Hybrid Conceptualism in Romanian Art,” Arta 20/21, 2016, pp. 14-15, who rightly points to various other Romanian artists engaging with landscape and folk practices at the time. Cf. Diana Marincu’s article in the same issue on the relevance of rural traditions, “I had Been Building the Universal City When I had Not Seen Any City at All,” Ibid., p. 34. One should not assume that the village of Mărgău is familiar to Cluj residents (Clujeni). In Ana Lupas: Drawing the Solemn Process (Paris: Les Presses du réel, 2021), Sebestyén Székely confesses that, despite its proximity to Cluj, for decades he knew Mărgău only as the site of Humid Installation; this link eventually led him to visit it recently, p. xix.) It is not that the artwork represents such changes, but rather it embodies them in structures that are both and neither fully urban nor rural.

In saying this I do not mean to claim dissident status for Lupaş’s art.(Caterina Preda argues that instead of dissident art we should think of Romanian postwar “alternative” art, abstraction being the main way to defy official dictates. Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). See also Amy Bryzgel, Performance Art in Eastern Europe Since 1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), pp. 241-45.) Not that there was nothing in the artist’s life and intellectual formation that could come into conflict with the state: notably, she is descended of several generations of intellectuals, some of whom faced censorship, surveillance and even imprisonment under the communist regime during the purges of the 1950s.(Alina Șerban, “Ana Lupaş”, in the feminist art resource Archive of Women Artists Research & Exhibitions (AWARE), at https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/ana-lupas/, accessed August 25, 2020, draws attention to the artist’s “family of Transylvanian Romanian intelligentsia, which experienced the political purges of the 1950s.” On the artist’s family, notably grandfather Ioan Lupaş (1880-1967), see my Sites of History, chapter 7.) But such a heritage, important as it is in understanding Lupaş’s patient, principled engagement with peasant life, precisely could not issue in any overtly critical gestures.(See Ileana Pintilie, “Questioning the East. Artistic Practice and Social Context on the Edge,” in Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-based Art in Late Socialist Europe, ed. Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak (New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 60.) Her work appeared in both official and unofficial contexts, in Romania and abroad, and was prominently featured in the official art journal, Arta, several times, along with the reproduction of Flying Carpet with Red Egg in a Nest (c. 1971), a work related thematically to Humid Installation.(Mihai Drişcu, “Structuri ale stilului, Ana Lupaş,” Arta, Vol. 8 (1971), pp. 12-13.) In an accompanying article, Arta editor Mihai Drişcu interprets the work formalistically as a spatialization of textiles, a playful ambient space “both of the momentary experience and the medium” to be distinguished strictly from hobby art. Lupaş is “distrustful” of work that doesn’t change, the article continues, creating instead spaces that can be directly experienced.(Ibid., p. 12. The other significant critic writing about Lupaş in 1977, Arghir, an Arta editor writing in English in Contemporary Artists, places her work largely in an ecological mode, but adds a lot of verbiage about ritual and “earthly happiness,” p. 576. Magda Cârneci counts Arghir and Drişcu among the leading critics of the time, writing on “the generation in full affirmation” and “the very young generation, which would manifest itself especially after the middle of the ‘70s.” Artele plastice în România: 1945-1989. Cu o addenda 1990-2010, 2nd ed. (Bucharest: Polirom, 2013), pp. 119-120, and 122 on Lupaş, who brings “a discreet but noticeable feminist coloring.”) Humid Installation was shown in the second issue of Arta in 1974, when the journal reported from the Young Artists Biennale in Paris, where the work was entitled Symbol for Peace. Of course, at the time of the article, the physical spaces of Humid Installation were gone—dried out—a good seven years. How and what does one experience in these memorial spaces of mediated cloth?

Commemorative Processes

Humid Installation, as it was definitively installed in Mărgău, was captured in artful close-ups as well as more neutral, but equally picturesque, panoramic views, which Lupaş also had screen-printed and double-exposed with a distinctive kite (zmeu), one of the artist’s recurring motifs. We can agree, having looked at its inception with some care, that the installation takes up and monumentalizes mundane work practices existing before and beyond the collectivization of agriculture, a process that successfully concluded, according to official accounts, in 1962.(See Gail Kligman and Katherine Verdery, Peasants Under Siege: The Collectivization of Romanian Agriculture, 1949-1962 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), pp. 88-149.) Cluj was notable, though by no means unique, among major Romanian cities surrounded by arable land, by the relatively sluggish pace of its collectivization, with only 37% of the land under state control in 1960.(See Table 2.5 in Kligman and Verdery, p. 144, based on Romanian statistics reported in John Michael Montias, Economic Development in Communist Romania (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1967). These statistics are skewed propagandistically, as can be seen by the rapid gains reported between 1960 and 1962, when many regions reported 100% land collectivization; Cluj, nevertheless, was only at 87% in 1962.) Things stood very differently a decade later, but one may safely assume that the residents of Mărgău remained familiar with such traditional labors as the bleaching or whitening of cloth, which involves repeatedly washing hemp or linen cloth and sun-drying in the open air, a late summer activity carried out shortly before harvest and connected with festivities and the coming of age of rural women.(See Tudor Pamfile and Mihai Lupescu, Cromatica poporului român (Bucharest: SOCEC & Sfetea / Leipzig: Otto Harrassowitz / Vienna: Gerold, 1914), pp. 172-78.) The work, in other words, was not just incidentally women’s work but a contemporary, sculptural, site-specific, and photographic meditation on such work, both its history and potentials for aesthetic preservation.

Ana Lupas, Preparatory Drawings for Memorial of Cloth, c. 1990. Courtesy the artist.

As legible as such practices remain, especially in the configurations of color photographs that convey a before-and-after temporality, Humid Installation is by no means a simple replication, nor a documentary anthology of folkways.(Which is not to say that it could not also be that. Consider the barrage of everyday anecdote, folklore and subversion in Radu Anton Roman’s Zile de pescuit [Fishing days] (Bucharest: Editura Cartea Românească, 1985).) Rather, it commemorates peasant practice monumentally, with all the ambiguity of an aesthetic object. The traditional utilitarian drying of cloth is staged and photographed for its own sake—a humid process. Most importantly, Humid Installation uses space, the social space of the village green, the political space of collectivized agriculture, and the sheer physical space of a fallow field, too steep for planting. Such an overlay of real and symbolic spaces was disputed in many Western interpretations of the events of 1968, but here they are quietly and subtly explored on a variety of registers without any reductive revolutionary rhetoric. The work’s insistent materiality—the heavy, but lyrically billowing cloth (which Lupaş sometimes displays rolled up under photographic prints of the action), the lost wood of the poles, the earth and air of Mărgău that took up the humidity, the celluloid film that registered these factors, sometimes superimposed—directs us to that space and helps us imagine it. One of the things I think the work, in all its material components, shows is the entanglement of the shift in economic systems with unpaid labor and care. Site-directedness is the term most appropriate for how this artwork at once calls up and memorializes a particular space in time: a complex aesthetic product and community action that is neither nostalgic nor assumes that equality is anywhere near.

That Humid Installation bore such potential for critical commemoration is perhaps evident if we turn to its most polemic instantiation, Rag Monument, which as mentioned was staged on Bucharest’s University Square in 1991, a year after the miner riots and only a year and a half after the death of Ceauşescu. The similarity of the Humid works might spur us to regard this instance as a hurried intervention, brought to bear jarringly, for a matter of weeks, on an urban space where its slow rural symbolism and materiality work by not fitting in. Such a reading, though plausible, is a mistake, for reasons having to do, as I have tried to show, both with Lupaş’s practice and the nature of the University Square space, which is as historically loaded as the work’s previous homes in Cluj and Mărgău. The history of communism, of its precursors and future, informs these sites equally but differently. Not that urban women don’t dry cloth outside: there are (or were) iron bars for hanging laundry all around Bucharest. But they do not occupy the front yard of the National Theater, from whose balcony a sole black-and-white photograph immortalizes Rag Monument. The cloth in Bucharest is dark and unyiedling, impregnated with asphalt, not swaying dynamically in the wind or changing in weight and dynamic tension as it dries, but rather hanging heavily, suggestive of mourning. The installation—made outside the dictates of the communist and the new ostensibly representative regime, but also without the peasant women who had been Lupaş’s collaborators and dramatis personae—can be seen as a memorial in a newly elegiac, even funereal mode. The kites and flying carpets of the early versions land heavily in the post-revolutionary space; the latent longing for freedom has turned into the metaphor of a material that is impossible to clean and fraying into rags, the cârpe of domestic female labor. Cast in shiny aluminum and planted triumphally in Dunkirk, the rows of frozen “cloth” recall as much the ruins of democratic protest as the hopes of a rural community on the cusp of violent transformation just two decades earlier.

Ten years after the appearance of Rag Monument, the pedestal of a removed Lenin statue in a public square on the outskirts of Bucharest was chosen as the future location of projects dealing with the communist past, an “anti-nostalgic” forum that “encourages a critical approach to the past and its symbols.”(Caterina Preda, “Project 1990 as an Anti-Monument in Bucharest and the Aestheticisation of Memory,” Südosteuropa 64 (2016), pp. 307-324, quote p. 310. Preda draws on James E. Young’s notion of the “anti-monument,” itself indebted to Jochen Gerz’s “countermonument” (Gegendenkmal). See Mechtild Widrich, Performative Monuments: The Rematerialisation of Public Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), chapter. 4.) Although Humid Installation and its variants made such projects possible in their restless search for new processes and materials of commemoration, and creative repurposing to new tasks of remembrance, they feel infinitely more indirect. The rolls of cloth seem abstract if not allegorical in their density of historical layering, their potential to refer to multiple pasts in the eyes of multiple, overlapping futures. One of the great unanswered questions of contemporary memorials, however formally or theoretically sophisticated they become, is how they will function, if at all, in contexts their creators and original audiences did not expect or even imagine. Reframing is part of the work, the work of all monument makers today and of Lupaş’s Humid Installation particularly. Maybe this is where its liberatory potential lies: in being able to draw new boundaries, without forgetting the old.

This article is part of the Special Issue Contemporary Approaches to Monuments in Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: