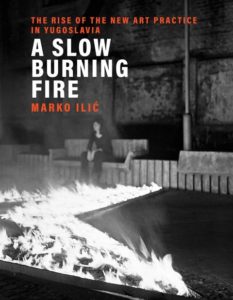

A Slow Burning Fire: The Rise of the New Art Practice in Yugoslavia

Marko Ilić, A Slow Burning Fire: The Rise of the New Art Practice in Yugoslavia (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2021), 384 PP.

To what extent does the term “institutional critique” adequately describe the work of the New Art Practice, Yugoslavia’s famous generation of conceptual artists? Scholars have taken a range of approaches to this question, from those who reject the term as associated with Western art histories, to those who see the New Art Practice’s dematerialized, socially critical artworks as a form of institutional critique responsive to local conditions. (For example, in her 2007 contribution to the journal Transversal on the nature of institutional critique in the post-Yugoslav region, Ana Dević writes that Yugoslavia has no history of institutional critique in the Western sense because of artists’ focus in the 1970s on exiting official gallery spaces and exploring alternative types of exhibition and collective affiliation. Dević, “To criticize, charge for services rendered, and be thanked,” Transversal (November 2007), https://transversal.at/transversal/0208/devic/en, accessed December 8, 2021. Ivana Bago, writing more recently, discusses the critical dematerialization and politicization of the art exhibition under the New Art Practice as a form of institutional critique, citing Goran Trbuljak as an important contributor to that development. Bago, “Dematerialization and Politicization of the Exhibition: Curation as Institutional Critique in Yugoslavia during the 1960s and 1970s,” Museum and Curatorial Studies Review, 2 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 7-37.) Marko Ilić’s new book A Slow Burning Fire: The Rise of the New Art Practice in Yugoslavia opens up an expanded understanding of the term institutional critique as it applies to Yugoslavia, by positing a tense, productive relation with state institutions as a defining feature of the New Art Practice across the historical scope of its activity from the late 1960s to the 1980s. A Slow Burning Fire presents Yugoslavia’s innovative conceptual movement through the prism of the country’s Student Cultural Centers (SKCs, sometimes referred to more simply as Student Centers) and the different types of aesthetic and political creativity, allegiance, and discord that they incubated. Simultaneously, the book’s ambition is much bigger: to provide a comprehensive history of the New Art Practice that aligns it centrally with the fate and legacy of Yugoslavia’s national project. Ilić’s key methodology for achieving that goal is social art history, which ultimately becomes both a strength and a blind spot of the book.

A Slow Burning Fire provides a nuanced representation of the Student Centers, their relationship to Yugoslav national politics, and the kinds of cultural agency that they enabled (and disenabled). The Student Centers were state-supported youth arts centers founded in the wake of the country’s massive 1968 student protests, in which students passionately, yet ultimately unsuccessfully, protested for a more genuine and truly egalitarian form of socialism. As such, the Student Centers were in one sense associated with political failure of the student movement, but also provided invaluable spaces for experimental culture and intellectual activity. A Slow Burning Fire proceeds via case studies of particular centers and of groups and exhibition spaces that offered additional alternatives to them, while also moving chronologically across those cases from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. Chapter 1 is devoted to the history of the well-known Zagreb SC Gallery in the late sixties, and Chapter 2 to Activities of 1968-72 at the Youth Tribute in Novi Sad, Vojvodina. The Youth Tribute was an organization similar to a Student Center but founded earlier, in 1954, which became a gathering place for experimental artists and cultural workers in the 1960s (p. 71). Chapter 3 then moves to the capital and the history of Belgrade’s famous SKC Gallery in the formative years from 1971 to 1976. Chapter 4 returns to Zagreb, analyzing the loose collective Group of Six Authors and the work of Podrum Gallery in the late 1970s. Chapter 5, devoted to the activities around Ljubljana’s Škuc gallery, looks at punk-influenced and dissident work by artists such as Dušan Mandić and Laibach. The final chapter, Chapter 6, analyzes the activities clustered around Café Zvono in Sarajevo, and the 1989 all-Yugoslav Dokumenta exhibition held in the same city.

A Slow Burning Fire provides a nuanced representation of the Student Centers, their relationship to Yugoslav national politics, and the kinds of cultural agency that they enabled (and disenabled). The Student Centers were state-supported youth arts centers founded in the wake of the country’s massive 1968 student protests, in which students passionately, yet ultimately unsuccessfully, protested for a more genuine and truly egalitarian form of socialism. As such, the Student Centers were in one sense associated with political failure of the student movement, but also provided invaluable spaces for experimental culture and intellectual activity. A Slow Burning Fire proceeds via case studies of particular centers and of groups and exhibition spaces that offered additional alternatives to them, while also moving chronologically across those cases from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. Chapter 1 is devoted to the history of the well-known Zagreb SC Gallery in the late sixties, and Chapter 2 to Activities of 1968-72 at the Youth Tribute in Novi Sad, Vojvodina. The Youth Tribute was an organization similar to a Student Center but founded earlier, in 1954, which became a gathering place for experimental artists and cultural workers in the 1960s (p. 71). Chapter 3 then moves to the capital and the history of Belgrade’s famous SKC Gallery in the formative years from 1971 to 1976. Chapter 4 returns to Zagreb, analyzing the loose collective Group of Six Authors and the work of Podrum Gallery in the late 1970s. Chapter 5, devoted to the activities around Ljubljana’s Škuc gallery, looks at punk-influenced and dissident work by artists such as Dušan Mandić and Laibach. The final chapter, Chapter 6, analyzes the activities clustered around Café Zvono in Sarajevo, and the 1989 all-Yugoslav Dokumenta exhibition held in the same city.

Ilić builds this history on sterling archival and secondary source research, and the book’s footnotes are in themselves a hugely valuable compendium of references. He marshals these resources to depict the Student Centers as incubators of layered discourses about art, the production of which involved numerous agents, including curators, critics, artists, and audiences. At several points, the book compellingly highlights how people navigated the Student Centers’ unique institutional contexts to define and defend visions of what experimental art could achieve. Those acts of navigation were responsive to local power struggles within the cultural sector, national politics, and the international zeitgeist of contemporary art. For example, Ilić discusses the decision by Želimir Koščević, a young art historian who curated exhibitions at Zagreb’s SC Gallery, on how to display the traveling show of the mail art section of the seventh Biennale des Jeunes from Paris (1971). Koščević just placed the still-packed box of mail art items in the gallery instead of unpacking and hanging them in the conventional way, in a gesture that sought both to push back against local viewers’ expectations and to trouble conceptual art’s cooptation by the market (p. 44).

Chapter 3, which again addresses the activities of Belgrade’s SKC, is especially effective at showing the interface between a local art scene and an international network, through its analysis of Raša Todosijević’s tongue-in-cheek engagement with the work of Joseph Beuys. Beuys visited the SKC for the April Meeting of 1974 after meeting Belgrade-based artists, including Todosijević, Marina Abramović, and Zoran Popović the year before, when the latter artists traveled to Edinburgh for the exhibition Eight Yugoslav Artists hosted by gallerist Richard Demarco (p. 129). Ilić convincingly frames Todosijević’s performance for the 1974 April Meeting, which took place just an hour before Beuys’s scheduled lecture/performance, as offering an alternative to the latter’s democratizing and romantic notion of art. Against that model, Todosijević “wanted to act as the catalyst that exhausted viewers, ambushed, and deceived them.” (p. 141) This juxtaposition positions Todosijević delicately as engaged in active dialogue with a then-dominant model of Western performance, but also as elaborating his own mode of audience address that can’t be reduced to a simple response to Beuys. At the same time as Ilić excavates the modes of audience address artists sought to promulgate, he demonstrates how actual reception could have unpredictable consequences, because audiences responded to works in ways that were shaped both by their expectations of aesthetic experience and their ideological climate. A particularly dramatic instance of this was the spontaneous audience destruction of works during the 1967 Hit Parade exhibition at SC Gallery. Ilić reads this destruction as simultaneously frivolous and hostile, speculating that it “may have been the result of a particularly tense economic climate, as Yugoslavia began developing a more liberal and world-dependent economy.” (p. 23)

A Slow Burning Fire brings out this kind of textured interplay of discourse, context, and reception not only in the major cities of Zagreb, Belgrade, and Ljubljana, but also in the more marginalized locations of Sarajevo and Novi Sad. This is perhaps the book’s most important intervention: a resituating of the New Art Practice’s geographic map to be truly national, and to consider the lasting impact of the region’s uneven wealth and industrial development on experimental art. Ilić’s nuanced depiction of Sarajevo in Chapter 6 positions it as a city coping with marginalization at multiple levels, from mainstream perceptions of its local language variant as an inferior departure from standard Serbo-Croatian (p. 254) to its lack of a Student Center, which meant that “throughout the 1970s [it] did not possess a single gallery that concerned itself with new movements and media.” (p. 257)

Ilić details the emergence of a local scene via the activities hosted by café Zvono, an ordinary bar that in 1979 opened itself to local art students for exhibitions and for social exchange connected to innovative art. Ilić describes Zvono’s modality as follows: “In a city that was for decades seen as being incapable of offering anything substantial to the wider Yugoslav cultural community, Zvono fostered an art that was ‘modern’ in its engagement and modes of display, but also ‘local’ in its understanding of its audience.” (p. 274) This formulation elegantly avoids framing artistic activity in a peripheral location as derivative, while also acknowledging how its local contribution was filtered through an engagement with modernism that might have seemed out-of-date in Zagreb, Belgrade, or Ljubljana. Ilić also uses the chapter to set up some productive and enlightening comparisons between the Ljubljana-based Scipion Nasice Sisters Theater’s now-canonical model of Tatlin’s tower that formed the set for their 1986 performance Baptism Under Triglav, and Sarajevo-based artist Aleksandar Saša Bukvić’s Wedding Cake à la Tatlin of the same year. Bukvić, who was both an academically trained sculptor and a pastry chef, made a model of the tower decorated with fake flowers, and passed out real chocolate cakes to viewers at the exhibition (pp. 270-71). Ilić describes both works as drawing on avant-garde histories to validate their local cultural climates (p. 273), thereby enabling readers to understand the intellectual commonalities as well as the very different cultural landscapes in which each practice unfolded.

Foundational to Ilić’s arguments throughout the book is the notion that the emergence of the New Art Practice was closely connected to Yugoslavia’s political history of the 1960s and 1970s. A Slow Burning Fire presents this context as encompassing major events in national politics such as the student protests of 1968 in Belgrade and the 1971 nationalist Croatian Spring to “the country’s opening up to world markets” (p. 24) and changes in its federative power structure. Indeed, political and economic context take such prominence that the book often drops the thread of art historical investigation to spend several pages at a time devoted to explaining the ins and outs of Yugoslavia’s evolution. This would not be such a problem if the book were framed equally as an intervention into Yugoslavia’s political history, but its research, organization, and sumptuous illustrations make it clear that it is not, and that art history as a discipline is the key horizon of its contribution.

Moreover, Ilić draws some very direct connections between art practices and political developments, such as when he argues that the activities of Zagreb’s Group of Six Authors and Podrum gallery “took on the task of illuminating the otherwise concealed shifting dynamics of state-society relations in Yugoslavia.” (p. 166) The Group of Six Authors were a bunch of friends who created so-called “exhibition-actions” together in public spaces, where they showed their individual artworks and talked with passersby. Ilić argues that their structure, in which they exhibited and socialized together but didn’t usually collaborate in authoring artworks, paralleled the relationship between the six Yugoslav republics (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia) established by the new 1974 constitution (p. 175). This new constitution strengthened the rights of the individual republics, ultimately resulting in an unworkably high threshold for collective decision-making. Though the new constitution was ratified at around the same time the Group of Six Authors started exhibiting together, equating their relationships as artists with the country’s federative structure or seeing their work as geared at the illumination of state-society dynamics is not adequate to either the artists’ understandings of their own practices or the reception of their work in its moment. It also does not hold up to close scrutiny of the artworks. Group of Six member Vlado Martek did, in fact, produce a 1990 print in which he juxtaposed the names of the group’s members over the republics in a roughly rendered map of the troubled country. Ultimately that work meditates on how fantasies of togetherness can be projected at multiple levels – from close relationships to the imagined nation – but also result in fracture and disappointment, ultimately providing only a deeply unstable basis for identity. A Slow Burning Fire overlooks the questions about how desire shapes the positions that people take up as narrators or subjects of history and nationhood that Martek’s work urges us to examine. Instead, it projects an alignment between art practice and national politics as unproblematized historical fact. This is symptomatic of the manner in which the book misses opportunities to attend to how artworks themselves mediated relationships to history and context in powerful and provocative ways.

The absence of artworks is nowhere more striking than in the treatment of the 1989 Yugoslav Dokumenta, which Ilić positions as a final statement about the vibrancy and interconnectedness of Yugoslavia’s experimental art scene, but without discussing a single artwork from the show save for its poster and public billboard. Partially restaged at the Moderna galerija Ljubljana in 2017, the 1989 Dokumenta was a presentation of works of huge formal diversity, with an overall emotionally heavy tone and a notable focus on questions of individual and collective relationships to history.(See “The Heritage of 1989, Case Study: The Second Yugoslav Documents Exhibition,” Moderna galerija Ljubljana, http://www.mg-lj.si/en/exhibitions/1997/the-second-yugoslav-documents-exhibition/, accessed December 8, 2021.) A close look at some of the artworks could have been useful in helping depict the exhibition not just as an act of local art organization amidst disintegrating political conditions, but as a trenchant working-through of the artists’ own fraught understandings of their relationship to the history unfolding around them.

A Slow Burning Fire was one of the last book projects in Central and East European art history acquired for MIT Press by former Executive Editor Roger Conover, before his recent retirement. Conover has deep intellectual and personal connections with artists and art historians in formerly socialist Europe, especially in the region of the former Yugoslavia, and his editorial leadership at MIT was pivotal for bringing those histories to English-speaking readers. Ilić’s focus on the sociability surrounding experimental art, the institutional networks that gave rise to it, and the types of internationalism it helped imagine align with other books published by MIT late in Conover’s tenure. I am thinking namely of New Tendencies: Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961-1978) (2016) by the late Armin Medosch and Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965 -1981 (2019) by Klara Kemp-Welch (who was also Ilić’s doctoral supervisor). Taken as a collective statement, these volumes assert the field’s definitive transcendence of notions of art under European socialism as culturally or geopolitically isolated, and make expansive claims for the region’s centrality to global contemporary art. They also demonstrate an affinity for ideas of connectivity and collectivity over and above questions of interiority or subjective experience on the part of artists or their audiences, or close engagement with the texture of art practice as such. Following this cohort of books and Conover’s retirement, what’s next for MIT, and more to the point, what kind of response or alternate direction might this wave of scholarship fuel within the field? We will all have to stick around to find out.