Sequences: Art of Yugoslavia and Serbia from the Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art

Sequences: Art of Yugoslavia and Serbia from the Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, October 2017 – June 2018

Following a decade-long renovation, the doors of the Belgrade Museum of Contemporary Art were finally thrown open again in October last year, attracting an eager audience to the debut exhibition, Sequences: Art of Yugoslavia and Serbia from the Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Showcasing some 300 works from the Museum’s collection, Sequences explores the trends and developments that shaped art across the former Yugoslavia throughout the 20th century. Through the exhibition, as Dejan Sretenović explains in the accompanying catalogue, the Museum seeks to offer “a new framework by which to become acquainted with and understand the art made on these territories,” and highlight the existence of a common Yugoslav heritage in contemporary artistic production.(Dejan Sretenović, “‘Sequences.’ The Reading Manual” in Sequences. Art of Yugoslavia and Serbia from the Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art (Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017), n.p.) In a political climate where notions of a Yugoslav idea and heritage are often treated with suspicion, the exhibition takes on a challenging and—as Sretenović and his team demonstrate—vital task.

The exhibition is structured as a series of eighteen sequences, which trace artistic research from the interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918-1941) through to the break up of the second (socialist) Yugoslavia in 1991, before concluding with a focus on the art in Serbia from the 1990s until today. The concept of sequences functions to describe artistic currents, tendencies and movements that are bound by time and space, or by a certain “poetic, linguistic and thematic relatedness.”(Ibid., n.p.) This proves a clever curatorial choice, as it draws a diverse and fragmented array of artworks into a conversation over common elements of the time and space in which they were developed. The sequences themselves are not equal in size, nor do they follow a strict chronological line, leaving open the prospect that they might be viewed and contemplated in isolation, as “micro-exhibitions with independent logic.”(Ibid., n.p.) The exhibition also distances itself from the concept of a singular, master-narrative, as the 18 sequences foreground five narrative frameworks that shaped the Yugoslav (and Serbian) scene—from art of the first half of the 20th century, to historical avant-gardes and neo-avant-gardes, post-war modernism, postmodernism and contemporary art—with each framework occupying one floor of the Museum’s five-story building.

The exhibition is structured as a series of eighteen sequences, which trace artistic research from the interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918-1941) through to the break up of the second (socialist) Yugoslavia in 1991, before concluding with a focus on the art in Serbia from the 1990s until today. The concept of sequences functions to describe artistic currents, tendencies and movements that are bound by time and space, or by a certain “poetic, linguistic and thematic relatedness.”(Ibid., n.p.) This proves a clever curatorial choice, as it draws a diverse and fragmented array of artworks into a conversation over common elements of the time and space in which they were developed. The sequences themselves are not equal in size, nor do they follow a strict chronological line, leaving open the prospect that they might be viewed and contemplated in isolation, as “micro-exhibitions with independent logic.”(Ibid., n.p.) The exhibition also distances itself from the concept of a singular, master-narrative, as the 18 sequences foreground five narrative frameworks that shaped the Yugoslav (and Serbian) scene—from art of the first half of the 20th century, to historical avant-gardes and neo-avant-gardes, post-war modernism, postmodernism and contemporary art—with each framework occupying one floor of the Museum’s five-story building.

Beginning on the ground floor, the first sequence is dedicated to “Bourgeois Modernism,” a dominant artistic trend during the interwar years that explored the bourgeois class and its world, and drew upon the visual language of Post-Impressionism, Expressionism and Cubism. Entering the Museum, visitors immediately encounter the large and sombre Funeral in Sićevo (1905) by Nadežda Petrović, an artist whose name in Serbia is synonymous with modern art. Funeral in Sićevo is a well-chosen opening to Sequences on two grounds. First, having been created during the First Yugoslav Art Colony in 1905 (thirteen years prior to the formation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), it speaks of the history of the Yugoslav idea, which solidified within the artistic domain well before becoming a political reality. In addition, with its composition and palette showing the influence of Petrović’s training in European art centers, this opening work introduces the notion of the history of Yugoslav art as a dynamic conversation between the center and the margins.

Other works in the opening sequence are bound by themes of domesticity and leisure in both urban and rural settings; they display an affinity with the style of Paul Cézanne, the colours of Amedeo Modigliani, and the moods of Giorgio De Chirico, as well as some timid hints of Cubist experimentation. The diversity of European influences in both subject and style that filtered through Yugoslav painting is well captured in the pairing of Milo Milunović’s Bistro (1922) with Marijan Trepše’s Composition (undated). The first, a family portrait set inside a bistro—a father, the bistro owner, standing in his work apron; a mother seated with her heavy arms crossed upon her white apron; their daughter full of poise, and their young son holding a green scooter—captures in subdued tones the quiet order of domesticity. The second portrays a bright outdoor village scene, with a woman with healthy red cheeks dominating center foreground, and scenes of rural work and leisure unfolding in the background.

Other works in the opening sequence are bound by themes of domesticity and leisure in both urban and rural settings; they display an affinity with the style of Paul Cézanne, the colours of Amedeo Modigliani, and the moods of Giorgio De Chirico, as well as some timid hints of Cubist experimentation. The diversity of European influences in both subject and style that filtered through Yugoslav painting is well captured in the pairing of Milo Milunović’s Bistro (1922) with Marijan Trepše’s Composition (undated). The first, a family portrait set inside a bistro—a father, the bistro owner, standing in his work apron; a mother seated with her heavy arms crossed upon her white apron; their daughter full of poise, and their young son holding a green scooter—captures in subdued tones the quiet order of domesticity. The second portrays a bright outdoor village scene, with a woman with healthy red cheeks dominating center foreground, and scenes of rural work and leisure unfolding in the background.

The second sequence contains works of Social Art, which maintain the figurative style of Bourgeois Modernism but depart from domestic themes, and instead engage critically with social and political issues. Prominent here are works by Zagreb collective Zemlja (Earth) and Belgrade group Život (Life), both of which used graphic art, with its lower production costs and ease of distribution, to draw attention to the plight of the worker during the 1930s.

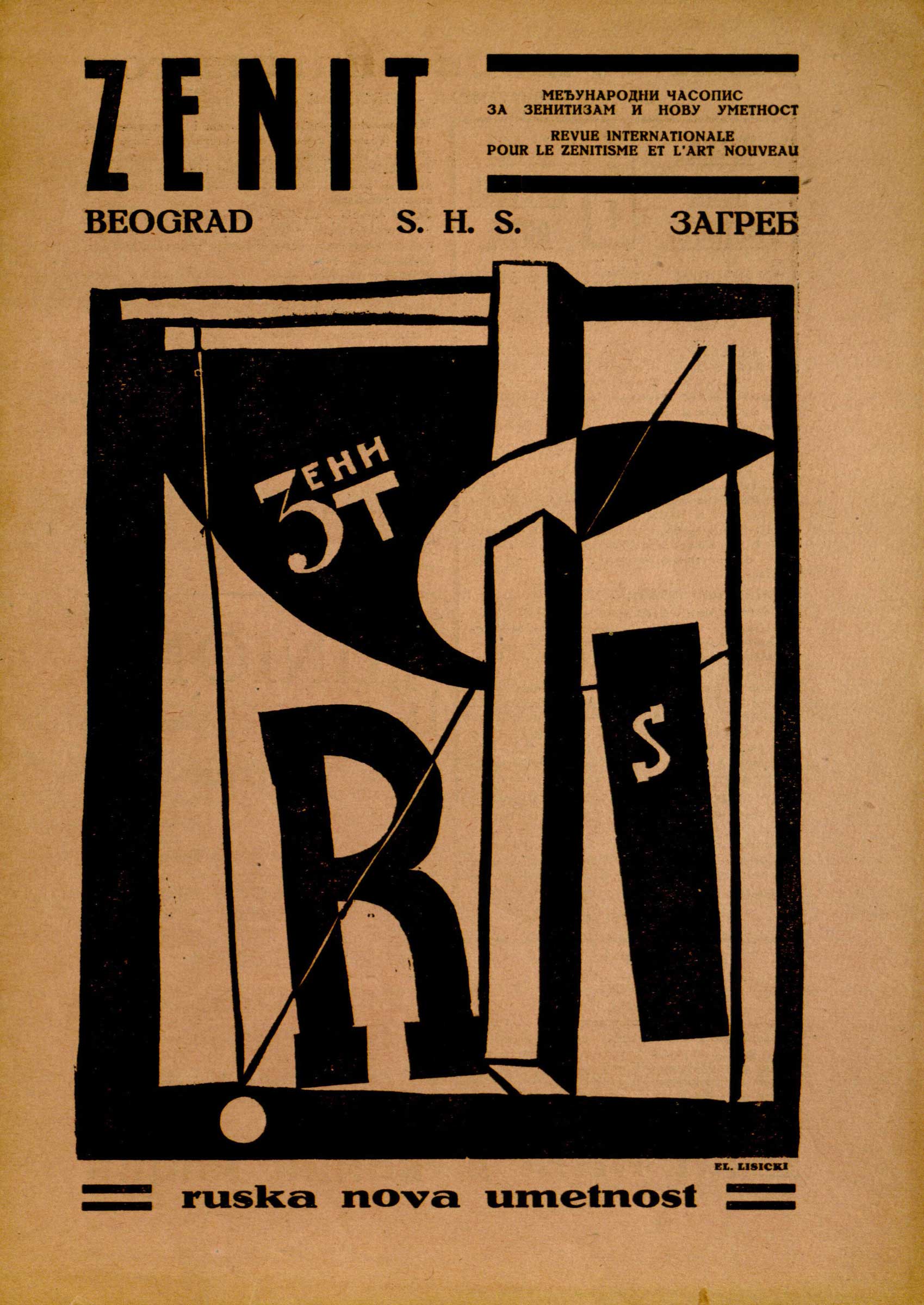

The second floor of the Museum is dedicated to sequences on the historical avant-gardes of the 1920s and 1930s, the neo-avant-garde tendencies that emerged between the 1950s and 1970s, and new artistic practices that extended avant-garde research into the fields of conceptual art, performance art, body art, land art, public actions, installations, and video art. Standing out in this selection is an area dedicated to the historical avant-garde, which easily functions as an exhibition in its own right. Here research in abstract painting, championed in the Expressionist and Cubist-inspired work of Ivan Radović, Jovan Bijelić and Mihailo S. Petrov, gives way to a sequence dedicated to Zenitism. Headed by poet Ljubomir Micić, Zenitism—which emerged in Zagreb and reached its maturity in Belgrade—sought to promote European avant-gardes while also exploring avant-garde language as a unique strategy for defining and promoting a distinctly Yugoslav artistic (and political) identity. Covers of the movement’s mouthpiece journal Zenit and abstract pieces by its chief protagonists Mihailo S. Petrov and Jo Klek are followed by a selection of works of Slovene Constructivism championed by Avgust Černigoj and Eduard Stepančič. This mini-exhibition culminates in an examination of Belgrade Surrealism, the creative potential of which is well captured in the piece Surrealist Wall—an art installation comprised of artefacts ranging from works by Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst to a Nigerian Gelede mask, which was assembled between 1926 and the 1960s by the leader of the movement, Marko Risitć.

The second floor of the Museum is dedicated to sequences on the historical avant-gardes of the 1920s and 1930s, the neo-avant-garde tendencies that emerged between the 1950s and 1970s, and new artistic practices that extended avant-garde research into the fields of conceptual art, performance art, body art, land art, public actions, installations, and video art. Standing out in this selection is an area dedicated to the historical avant-garde, which easily functions as an exhibition in its own right. Here research in abstract painting, championed in the Expressionist and Cubist-inspired work of Ivan Radović, Jovan Bijelić and Mihailo S. Petrov, gives way to a sequence dedicated to Zenitism. Headed by poet Ljubomir Micić, Zenitism—which emerged in Zagreb and reached its maturity in Belgrade—sought to promote European avant-gardes while also exploring avant-garde language as a unique strategy for defining and promoting a distinctly Yugoslav artistic (and political) identity. Covers of the movement’s mouthpiece journal Zenit and abstract pieces by its chief protagonists Mihailo S. Petrov and Jo Klek are followed by a selection of works of Slovene Constructivism championed by Avgust Černigoj and Eduard Stepančič. This mini-exhibition culminates in an examination of Belgrade Surrealism, the creative potential of which is well captured in the piece Surrealist Wall—an art installation comprised of artefacts ranging from works by Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst to a Nigerian Gelede mask, which was assembled between 1926 and the 1960s by the leader of the movement, Marko Risitć.

Subsequent sequences on this floor trace the methods used in post-war Yugoslavia by artists who were keen to explore creative avenues that had been opened by the historical avant-gardes. Artistic research by the EXAT 51 Neo-constructivist group is showcased through pieces such as Vjenceslav Rihter’s Divided Sphere II (1967) and Sge I (1969). These works are juxtaposed with others that were similarly inspired by the interplay between art and science, including works associated with the Zagreb-based New Tendencies movement. This science-driven visual research—beautifully captured in the lumino-kinetic objects from the late 1960s to mid-1970s of Koloman Novak—then gives way on the Museum’s sun-filled second floor to a series of Conceptualist works exploring the nature of art, and the role of artists and cultural institutions.

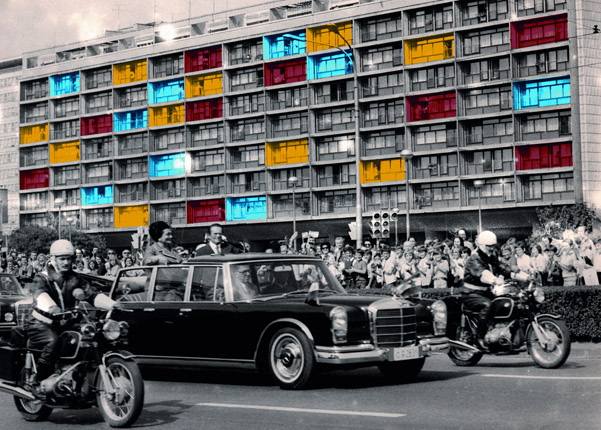

Elsewhere, provocative interventions into public space such as Balint Szombathi’s march through the Hungarian capital carrying a portrait of Lenin in Lenin in Budapest (1972) precede Marina Abramović’s video piece Freeing the Memory (1976). Though somewhat disorienting, this rapid-fire sequence of varied methods and approaches provides rare insight into how radical artistic research functioned under socialism. Indeed, contemplation of the dynamic between modernism, avant-gardism, and the Yugoslav brand of socialism in Sanja Iveković’s New Zagreb (People behind Windows) (1979) provides an important reference point. A black and white newspaper photograph of an official Zagreb visit by Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito and his wife Jovanka in 1979 serves as a starting point, with a police-escorted car containing the President and his wife in the foreground, an elated crowd in the middle ground, and a large modernist apartment building in the background. While people can be seen watching the President pass by behind the windows of the building, the empty balconies reflect an official security order. The artist highlights the apartments of those watching on by painting their individual rectangles in blue, yellow, or red, turning this modernist structure into a flat, Mondrian-like abstract surface. With a Mondrian composition now forming the backdrop for Tito’s motorcade, this is an image of competing modernisms: one emanating in a cool and orderly fashion from the center, and a different, Yugoslav rendering of modernisation (embodied in the figure of Tito), which is neither Soviet nor Western, but unaligned and independent. Equally, by drawing playful attention to the enforced order of this scene, the image highlights the ambiguity of modernist (and avant-gardist) projects, which hold equal potential for emancipation as they do for oppression.

Elsewhere, provocative interventions into public space such as Balint Szombathi’s march through the Hungarian capital carrying a portrait of Lenin in Lenin in Budapest (1972) precede Marina Abramović’s video piece Freeing the Memory (1976). Though somewhat disorienting, this rapid-fire sequence of varied methods and approaches provides rare insight into how radical artistic research functioned under socialism. Indeed, contemplation of the dynamic between modernism, avant-gardism, and the Yugoslav brand of socialism in Sanja Iveković’s New Zagreb (People behind Windows) (1979) provides an important reference point. A black and white newspaper photograph of an official Zagreb visit by Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito and his wife Jovanka in 1979 serves as a starting point, with a police-escorted car containing the President and his wife in the foreground, an elated crowd in the middle ground, and a large modernist apartment building in the background. While people can be seen watching the President pass by behind the windows of the building, the empty balconies reflect an official security order. The artist highlights the apartments of those watching on by painting their individual rectangles in blue, yellow, or red, turning this modernist structure into a flat, Mondrian-like abstract surface. With a Mondrian composition now forming the backdrop for Tito’s motorcade, this is an image of competing modernisms: one emanating in a cool and orderly fashion from the center, and a different, Yugoslav rendering of modernisation (embodied in the figure of Tito), which is neither Soviet nor Western, but unaligned and independent. Equally, by drawing playful attention to the enforced order of this scene, the image highlights the ambiguity of modernist (and avant-gardist) projects, which hold equal potential for emancipation as they do for oppression.

Petar Lubarda’s 1951 piece Fantastic Landscape stands as a symbolic opening for the sequences displayed across the Museum’s third floor. Indeed, the original unveiling of this work in a Belgrade exhibition signalled an official break with Socialist Realism, which followed the political fall-out between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in 1948, and announced a new direction in Yugoslav cultural politics. Abstract works evoking dramatic landscapes, figurative paintings and sculptures that articulate the drama of high modernism and the associated sense of anguish, alienation, violence and death are here placed against works that draw on principles of Minimal Art and American Post-Painterly Abstraction to build a story of the phenomenon that was termed Socialist Modernism. Spanning broadly the same 1950s-1970s period as works shown on the second floor, art produced under the Socialist Modernism umbrella enjoyed full institutional support in socialist Yugoslavia, unlike those trends represented on the floor below. Ranging from contemplative existentialist landscapes such as Vladimir Veličković’s Landscape of Dead Birds (1962) to Marij Pregelj’s Diptych (1967) which evokes the aesthetic of Francis Bacon, this art looks out towards international trends, yet does so while remaining conspicuously politically neutral.

Petar Lubarda’s 1951 piece Fantastic Landscape stands as a symbolic opening for the sequences displayed across the Museum’s third floor. Indeed, the original unveiling of this work in a Belgrade exhibition signalled an official break with Socialist Realism, which followed the political fall-out between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in 1948, and announced a new direction in Yugoslav cultural politics. Abstract works evoking dramatic landscapes, figurative paintings and sculptures that articulate the drama of high modernism and the associated sense of anguish, alienation, violence and death are here placed against works that draw on principles of Minimal Art and American Post-Painterly Abstraction to build a story of the phenomenon that was termed Socialist Modernism. Spanning broadly the same 1950s-1970s period as works shown on the second floor, art produced under the Socialist Modernism umbrella enjoyed full institutional support in socialist Yugoslavia, unlike those trends represented on the floor below. Ranging from contemplative existentialist landscapes such as Vladimir Veličković’s Landscape of Dead Birds (1962) to Marij Pregelj’s Diptych (1967) which evokes the aesthetic of Francis Bacon, this art looks out towards international trends, yet does so while remaining conspicuously politically neutral.

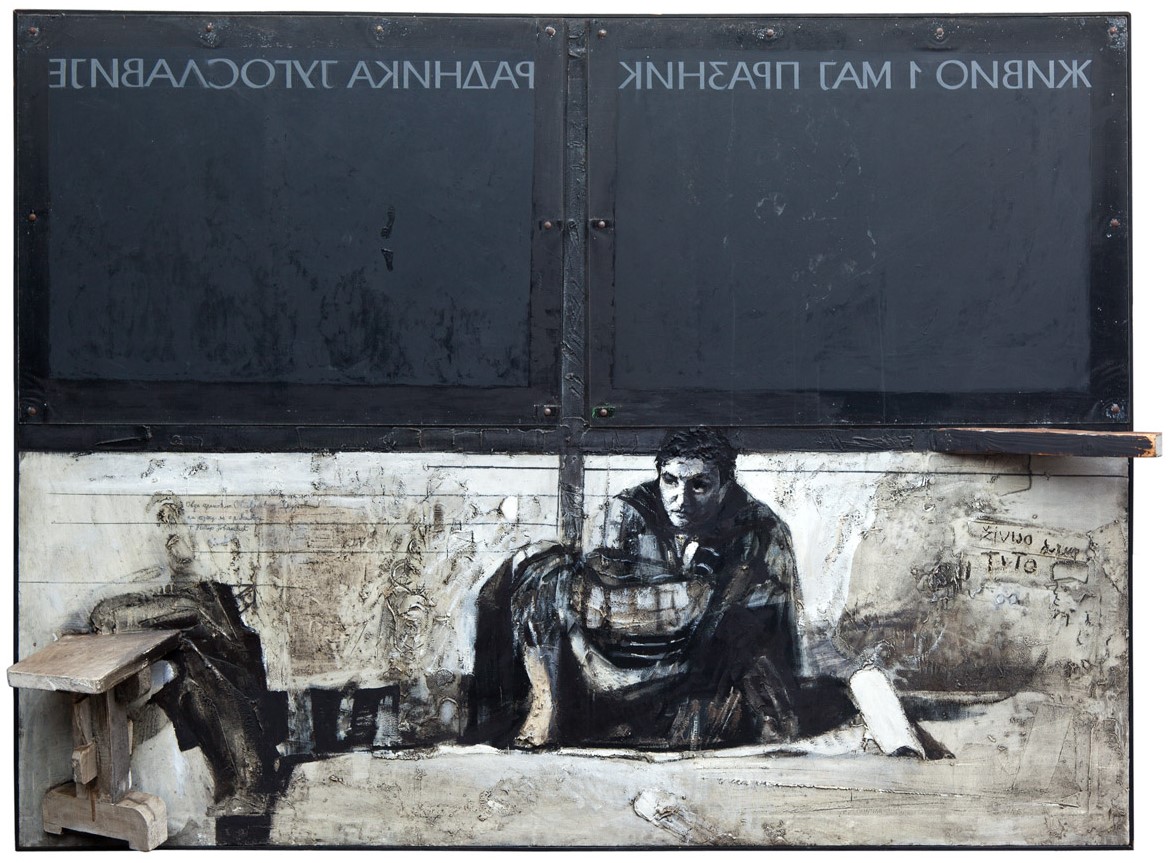

Politics is reserved for the fourth floor, with sequences here covering New Objectivity (an important feature of the Belgrade art scene in the 1960s), post-modern tendencies in Yugoslavia, and the new wave in photography, which emerged in the late 1970s. Marked by a return to figurative and narrative art, and framed by the spirit of 1968, works across this floor engage with themes of state violence, the crisis of political legitimacy, and economic instability. Dušan Otašević’s installation Comrade Tito, White Violet, Our Youth Loves You (1969), which parodies the cult of Tito, is cleverly paired with Miodrag Mića Popović’s Gvozden in Lodging for the Night on the Way to FR Germany (1970), which depicts one of the many Yugoslav guest workers (Gastarbeiter) who left the socialist motherland bound for Germany, in pursuit of a better life. Placed one across from one another, clownish propaganda is reflected against grey reality, as between them these two pieces recreate the ideological vacuum that defined the socialist experience. The work by Petar Omčikus, The Riddle of the Helmet (1971), stands out with its near-abstract rendering of riot police,

Politics is reserved for the fourth floor, with sequences here covering New Objectivity (an important feature of the Belgrade art scene in the 1960s), post-modern tendencies in Yugoslavia, and the new wave in photography, which emerged in the late 1970s. Marked by a return to figurative and narrative art, and framed by the spirit of 1968, works across this floor engage with themes of state violence, the crisis of political legitimacy, and economic instability. Dušan Otašević’s installation Comrade Tito, White Violet, Our Youth Loves You (1969), which parodies the cult of Tito, is cleverly paired with Miodrag Mića Popović’s Gvozden in Lodging for the Night on the Way to FR Germany (1970), which depicts one of the many Yugoslav guest workers (Gastarbeiter) who left the socialist motherland bound for Germany, in pursuit of a better life. Placed one across from one another, clownish propaganda is reflected against grey reality, as between them these two pieces recreate the ideological vacuum that defined the socialist experience. The work by Petar Omčikus, The Riddle of the Helmet (1971), stands out with its near-abstract rendering of riot police,  and will no doubt evoke memories of similar scenes on Belgrade streets during the anti-Milošević protests of the 1990s for the local audience. Also captivating within this space is the superb The Days of Sorrow and Pride (1980/1992) by Goranka Matić, which consists of a series of photographs of Tito’s portraits placed in shop windows after his death in 1980, and recreates the sense of foreboding that dominated society in the decade leading up to the breakup of Yugoslavia.

and will no doubt evoke memories of similar scenes on Belgrade streets during the anti-Milošević protests of the 1990s for the local audience. Also captivating within this space is the superb The Days of Sorrow and Pride (1980/1992) by Goranka Matić, which consists of a series of photographs of Tito’s portraits placed in shop windows after his death in 1980, and recreates the sense of foreboding that dominated society in the decade leading up to the breakup of Yugoslavia.

The two final sequences, housed on the top floor, are dedicated to Serbian art of the 1990s and contemporary art from both Serbia and elsewhere from 2000 to the present. Within the Museum, the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991 and the ensuing fratricidal war signal a change in focus from the Yugoslav to the Serbian context. The end of Yugoslavia and the dramatic redrawing of borders along ethnic and national lines does not, however, mark an end to the development of artistic narratives within the common Yugoslav space. Artistic production in Serbia between the 1991 breakup and the ousting of Slobodan Milošević in 2001 operated against a background of war, fervent nationalism, near total economic collapse, and a profound crisis in social values—yet it maintained plurality and interest in methods and approaches that had been championed in earlier decades. Tanja Ostojić’s Personal Space, performed on several occasions throughout the 1990s, exemplifies this argument of continuity. Completely depilated and covered in white marble dust, Ostojić uses her own body, free of any markers, to defy an official ideology that aggressively forced national, ethnic, religious and gender categories upon the population by eliminating any departure from the norm. A powerful statement on the state of affairs in 1990s Serbia, Personal Space is also firmly grounded in the Yugoslav avant-garde heritage, which had itself been formed through an ongoing conversation with the international scene, and an awareness of its own specificities.

The two final sequences, housed on the top floor, are dedicated to Serbian art of the 1990s and contemporary art from both Serbia and elsewhere from 2000 to the present. Within the Museum, the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991 and the ensuing fratricidal war signal a change in focus from the Yugoslav to the Serbian context. The end of Yugoslavia and the dramatic redrawing of borders along ethnic and national lines does not, however, mark an end to the development of artistic narratives within the common Yugoslav space. Artistic production in Serbia between the 1991 breakup and the ousting of Slobodan Milošević in 2001 operated against a background of war, fervent nationalism, near total economic collapse, and a profound crisis in social values—yet it maintained plurality and interest in methods and approaches that had been championed in earlier decades. Tanja Ostojić’s Personal Space, performed on several occasions throughout the 1990s, exemplifies this argument of continuity. Completely depilated and covered in white marble dust, Ostojić uses her own body, free of any markers, to defy an official ideology that aggressively forced national, ethnic, religious and gender categories upon the population by eliminating any departure from the norm. A powerful statement on the state of affairs in 1990s Serbia, Personal Space is also firmly grounded in the Yugoslav avant-garde heritage, which had itself been formed through an ongoing conversation with the international scene, and an awareness of its own specificities.

That the history of Yugoslav art could have been told in other ways and from other perspectives is something that the curators of Sequences openly admit. In their selection and arrangement, however, the exhibited works combine to present a compelling story of a diverse, fragmented and yet still common Yugoslav artistic space. In insisting that this Yugoslav heritage stubbornly resists any dissection along nationalist lines, and by demonstrating the continued influence of this history on nations that emerged from the breakup of Yugoslavia, this exhibition is an important intervention into the contemporary politics of memory in Serbia, and indeed across a region in which nationalist sentiment continues to cast an ominous shadow.

That the history of Yugoslav art could have been told in other ways and from other perspectives is something that the curators of Sequences openly admit. In their selection and arrangement, however, the exhibited works combine to present a compelling story of a diverse, fragmented and yet still common Yugoslav artistic space. In insisting that this Yugoslav heritage stubbornly resists any dissection along nationalist lines, and by demonstrating the continued influence of this history on nations that emerged from the breakup of Yugoslavia, this exhibition is an important intervention into the contemporary politics of memory in Serbia, and indeed across a region in which nationalist sentiment continues to cast an ominous shadow.

The re-opening of the Museum is a public demonstration of the Serbian Government’s commitment to restoring Belgrade’s status as a European cultural center, following decades of isolation and decay. This intention is further underscored by official support for high-profile future events within its walls, including an exhibition by Marina Abramović planned for 2019 that was personally negotiated by Prime Minister Ana Barnabić. Of course, whether a regime with direct links to the ruling parties of the 1990s will be an earnest custodian of Yugoslav art and its internationalist orientation remains to be seen—but Sequences certainly provides a platform for a different kind of conversation on the country’s past.

Sequences is open until June, when some of its sections will be removed to make room for a series of temporary exhibitions.