Sitting together. Parallel Chronologies of Coincidences in Eastern Europe

transit.sk, Bratislava, Slovakia – December 13, 2016 to February 25, 2017

A black and white photograph portrays a group of people in a natural environment like a meadow; they are eating and conversing while sitting in a circle. We can deduce from their garments and the hair in movement that the weather is fresh and windy. After a few seconds, we distinguish a small, dark-colored animal that is being pet by one of the participants. The animal is a lamb, a particular Ethiopian species borrowed from the zoo for this occasion; it is also the main character of this informal gathering, organized by Slovak artist Peter Bartoš, and known as Grazing a Lamb (1979).

On Easter Sunday, Peter Bartoš invited a handful of friends, including artists ?ubomír ?ur?ek, Ján Budaj, Július Koller, Kveta Fulierová and her daughter, and art historian Tomáš Štrauss, to climb up a hill near Bratislava and spend the afternoon together. Some of them brought their photo camera and spontaneously documented the afternoon.

More than three decades later, the artist Petra Feriancová addressed traces and memories of the event described above in a recent installation with Kveta Fulierová’s photographs and with a publication that collects images and narratives about the gathering by Peter Bartoš and other participants.(Petra Feriancová, On Directing Air 1, Peter Bartoš: Grazing a Lamb, 1979. An Attempt to Reconstruct an Afternoon (Bratislava : Sputnik Editions, 2016).) In Feriancová’s publication, In the latter, personal and collective memories engage in a polyphonic process of recollection in which ellipses and absences count as much as the story that is being told. Such a back and forth between past creative activities and their present readings is at the core of Sitting Together. Parallel Chronologies of Coincidences in Eastern Europe, which raises crucial issues concerning the interpretation and historicization of Eastern European art from the early 1970s to the present.(I am particularly thankful to Zsuzsa László and Petra Feriancová for their availability in discussing the project during my visit to the exhibition in Bratislava and afterwards, while writing this review.) The show, curated by Zsuzsa László and Petra Feriancová in collaboration with artists and art historians from Slovakia and Hungary, is an outcome of the collaborative project Parallel Chronologies that since 2009 has endeavored to recover curatorial and artistic experiences developed in Eastern Europe between 1950 and 1989, and to articulate them as constellations of events and related concepts.(Parallel Chronologies was started by Dóra Hegyi and Zsuzsa László in the form of a research exhibition and a symposium in Budapest with the aim to “present an international network of professional relationships, documents of exhibitions, events, and art spaces instead of the mere display of artworks from the period.” The project fills a gap most of the thematic institutional exhibitions dedicated to Eastern European have left. Focusing on exhibitions history, it “proposes a methodology with which documents and factual information as well as legends and cults can be researched, processed and displayed in an exhibition.” Dóra Hegyi and Zsuzsa László, “How Art Becomes Public” in Dóra Hegyi, Sándor Hornyik and Zsuzsa László (eds.), Parallel Chronologies. An Exhibition in Newspaper Format, Budapest : tranzit.hu, 2011. See the project’s website http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/ (Last accessed 16 March 2017).) Far from the search for archetypical figures and objects that characterized a number of historiographic and curatorial projects in the 1990-2000s, Parallel Chronologies is, according to László, “not about establishing (new) names in the international canon of neo-avant-garde art, as it does not undertake the task to survey and promote complete oeuvres.”(Zsuzsa László, in an email interview from the author, 9 March 2017.) In line with these intentions and relying on a series of materials partially collected as part of the research for Parallel Chronologies, Sitting Together explores these areas of convergence, socialization, and the collective or individual production of knowledge that surged from exhibitions and events in which artists and cultural actors from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia were involved during the 1970s, proposing a path divided into three “constellations” of documents.

The first constellation, entitled “International Artists Meetings. How Can We Talk about Eastern Europe?”, takes a step back to contemplate the role artistic events on both sides of the Iron Curtain played in the process of making visible and defining artistic practices from socialist Eastern Europe. It displays a chronology of landmark exhibitions, artists gatherings, and publications that contributed to shaping certain ideas of “Eastern European art”, as well as their reception and (mis-)understanding. Some of these cases have already been recognized for their crucial contributions to East-West exchanges, such as Klaus Groh’s book Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa (1972) or the NET launched that same year by Jaros?aw Koz?owski and Andrzej Kosto?owski; others are less well known and deserve further examination, such as the Danuvius Bienale in Bratislava (1968), Róbert Cyprich’s Red Year project, or the cycle of drawing exhibitions held in Pécs, Hungary, between 1980 and 1984. We could add to this other events such as Encuentros de Pamplona (1972) in Spain, in which a sizeable number of Czech and Slovak artists participated, as well as, in the extra-European context, exhibitions organized by the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires or the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC-USP). All of these events made important contributions to the spreading of information and artworks from Eastern Europe in other latitudes.

The first constellation, entitled “International Artists Meetings. How Can We Talk about Eastern Europe?”, takes a step back to contemplate the role artistic events on both sides of the Iron Curtain played in the process of making visible and defining artistic practices from socialist Eastern Europe. It displays a chronology of landmark exhibitions, artists gatherings, and publications that contributed to shaping certain ideas of “Eastern European art”, as well as their reception and (mis-)understanding. Some of these cases have already been recognized for their crucial contributions to East-West exchanges, such as Klaus Groh’s book Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa (1972) or the NET launched that same year by Jaros?aw Koz?owski and Andrzej Kosto?owski; others are less well known and deserve further examination, such as the Danuvius Bienale in Bratislava (1968), Róbert Cyprich’s Red Year project, or the cycle of drawing exhibitions held in Pécs, Hungary, between 1980 and 1984. We could add to this other events such as Encuentros de Pamplona (1972) in Spain, in which a sizeable number of Czech and Slovak artists participated, as well as, in the extra-European context, exhibitions organized by the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires or the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC-USP). All of these events made important contributions to the spreading of information and artworks from Eastern Europe in other latitudes.

However, what is to be emphasized here is the rational chronological scheme through which these events are presented in the context of Sitting Together’s first “constellation.” This decision–in favor of chronology–is not innocent; rather it directly refers to the need for building and consolidating contextual tools to address the region’s artistic interconnections and challenge the idea of isolated national entities within an Eastern block that is itself seen as being isolated from other geopolitical realms. In this respect, establishing a chronology has clear social and political implications that resonate with the task of self-historicization and the more or less systematic creation of archives in the 1970-80s by György and Julia Galántai, Zsófia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek or Július Koller, among others, as a way to mitigate the limited opportunities for publicity available for progressive events.(See: Sitting Together, exhibition statement, December 2016.)

However, what is to be emphasized here is the rational chronological scheme through which these events are presented in the context of Sitting Together’s first “constellation.” This decision–in favor of chronology–is not innocent; rather it directly refers to the need for building and consolidating contextual tools to address the region’s artistic interconnections and challenge the idea of isolated national entities within an Eastern block that is itself seen as being isolated from other geopolitical realms. In this respect, establishing a chronology has clear social and political implications that resonate with the task of self-historicization and the more or less systematic creation of archives in the 1970-80s by György and Julia Galántai, Zsófia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek or Július Koller, among others, as a way to mitigate the limited opportunities for publicity available for progressive events.(See: Sitting Together, exhibition statement, December 2016.)

Modern art history has defined artist activities and productions in terms of their simultaneity or non-simultaneity with what was occurring in what it considered the center – i.e. Western Europe and, from the second half of the twentieth century, the United States. In this sense, “chronology” cannot be dissociated from the problem of geography and ideology, in other words, from the spatial distribution of power.(Up to recently, differences in terms of information and accessibility could be observed within the former Eastern Bloc. In this context, Zsuzsa László recalls that in the 1990s-2000s, non-object based art was much slower to enter collections and international exhibitions in Hungary than elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Zsuzsa László, email interview from the author, 9 March 2017. (see below, Note 9)) Sitting Together questions such a distribution, first by rejecting in its chronology any kind of differentiation or hierarchy between events held in the West and in the East, and then by highlighting frames of interpretation commonly applied to artistic practices from Eastern Europe.

One of these frames opposes state-supported culture to dissident art. Particularly seductive to a Western leftist intelligentsia in search of political archetypes, the narrative of dissidence undergirded a large number of cultural initiatives, the most explicit being undoubtedly the controversial Biennale del Dissenso in Venice (1977) whose title performed the inscription and consecration of political commitment as art’s and artists’ fundamental responsibility.(The self-designation by artists as dissidents (or not), and the possible fluctuations of such a position over the time is a fascinating issue, and it is clear that such a label not only belonged to Western observers but was endorsed by the protagonists themselves as well. Peter Bartoš retrospectively designated what happened during Grazing the Lamb as a “meeting of dissent,” while other participants interviewed by Petra Feriancová did not share his view (“An Afternoon Grazing a Lamb. In Conversation with Peter Bartoš 17.11.2016”, in Petra Feriancová, 2016, 3).) One of the obvious risks of seeing unofficial or non-conformist artists from formerly Socialist countries through the exclusive lens of the struggle against Soviet-style regimes was, and still is, to maintain artists captive under a general frame that leaves little space for the expression of other critical postures, such as feminism, or for references to more specific or local issues.

![Exhibition view, From People’s Education to the Democratization of Art. The Neo-avant-garde Artist as Educator of [the] People. Image courtesy of tranzit.sk. Photo: Adam Šakový.](https://artmargins.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/6_Exhibition_view_Artist_as_Educator_Adam_Sakovy.jpg) To challenge the narrative of dissidence and its dialectical regime, Sitting Together. reintroduces the idea of “coincidence”, first coined and empirically explored by Hungarian art historian László Beke in the 1970s. While Beke considered coincidence “a form of art, more precisely a readymade, something that you have to find and that you cannot make,” in the context of Sitting Together, the term refers to zones of contact and interaction established both within and outside of Eastern Europe.(László Beke quoted in Sitting Together, Budapest/Bratislava: tranzit.hu and tranzit.sk, 2016, 5. In the introduction, Beke is designated as a“persistent collector of coincidences.”) In Zsusza László’s words, the choice of this trope “also connects to approaching the art of the era through exhibition history, which also examines situations in which various players coincide, especially if we don’t just reconstruct artistic/curatorial intentions but look at them in interactions with circumstances and processes outside of their control.”(Zsuzsa László, email interview from the author, 9 March 2017.) In this sense, we could see coincidences as the primary matter of a historiographic approach that focuses on movements and trajectories rather than static artifacts and discourses.

To challenge the narrative of dissidence and its dialectical regime, Sitting Together. reintroduces the idea of “coincidence”, first coined and empirically explored by Hungarian art historian László Beke in the 1970s. While Beke considered coincidence “a form of art, more precisely a readymade, something that you have to find and that you cannot make,” in the context of Sitting Together, the term refers to zones of contact and interaction established both within and outside of Eastern Europe.(László Beke quoted in Sitting Together, Budapest/Bratislava: tranzit.hu and tranzit.sk, 2016, 5. In the introduction, Beke is designated as a“persistent collector of coincidences.”) In Zsusza László’s words, the choice of this trope “also connects to approaching the art of the era through exhibition history, which also examines situations in which various players coincide, especially if we don’t just reconstruct artistic/curatorial intentions but look at them in interactions with circumstances and processes outside of their control.”(Zsuzsa László, email interview from the author, 9 March 2017.) In this sense, we could see coincidences as the primary matter of a historiographic approach that focuses on movements and trajectories rather than static artifacts and discourses.

If a “coincidence” refers primarily to the conjunction of artistic experiment, friendship, and a willingness to communicate, in Sitting Together, coincidences are also contemplated as situations in which experiences are not only empathetically shared, but can also be accompanied by the tensions, misunderstandings and conflicts inherent to any encounter with an “other”. The exhibition highlights two cases in which such tensions were either successfully channeled or where, on the contrary, they burst: first, the meeting of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists organized by László Beke at György Galántai’s Chapel Studio at Balatonboglár in 1972, and, second, the exhibition Works and Words held at De Appel and other locations in Amsterdam in 1979. How were these experiences retrospectively narrated and written about? According to Beke, the “Meeting” was a “fantastic potlatch”, the “highlight of the Hungarian, Slovak and Czech friendship.”(László Beke, in the video-recording of the Potlatch of Archives held on September 12th, 2016 at tranzit.sk, Bratislava. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCyIG_dAYh8 (Last accessed 24 February 2017).) While the recent history of these three countries has not been without tensions and resentment, this episode is recalled as a remarkable example of transnational collaboration held in a non-institutional environment in Eastern Europe.(Among the possible reasons for “hostility” after 1968 is the fact that Hungarian troupes were involved in the repression of the Czechoslovak Spring, since Hungary was a member of the Warsaw pact.) Considering the increasing number of studies and projects that address international networks of artistic friendship and solidarity, it seems essential not to abandon a closer view in order to identify possible cultural frictions and competing identities associated with processes of transnational communication and exchange.(See Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg-Glatigny, Piotr Piotrowski (eds.), Art Beyond Borders. Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe 1945-1989 (Budapest: CEU Press, 2016). The book is an example of an approach articulated around cases of people and objects in movement, combining global analysis with specific case studies.)

If Beke’s Meeting was an inspired potlatch, in the case of Works and Words, the attempt to generate dialogue–this time involving participants from Western and Eastern Europe–resulted in frustration and protest by the Eastern European artist participants against being stereotyped, and against the erroneous identification, by Western participants, of non-aligned Yugoslavia with the Eastern Bloc. A letter sent to the exhibition organizers by Yugoslav artist Goran Djordjević denounced a “ghetto exhibition” whose significance was, according to Djordjević, “reduced to its political dimension (dissident exotic), while the nature of the works themselves, their problematic character and significance are pushed in the background.”(For more details on this episode see Jelena Vesi?, “Works and Words. Early critique of the discourse of East European art,” in Parallel Chronologies online, http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/works-and-words-early-critiques-of-the-discourse-of-eastern-european-art/ (Last accessed 16 March 2017).)  One year earlier, Hungarian and West German artists Gábor Bódy and Marcel Odenbach had well captured such an egregious failure of communication through a simple action entitled Conversation between East and West (1978), in which both artists were stuck in a never-ending and entirely futile attempt to speak to each other.

One year earlier, Hungarian and West German artists Gábor Bódy and Marcel Odenbach had well captured such an egregious failure of communication through a simple action entitled Conversation between East and West (1978), in which both artists were stuck in a never-ending and entirely futile attempt to speak to each other.

If Sitting Together seeks to escape from the simplistic association of art from socialist Eastern Europe with the idea of dissidence, it also avoids pitting official, state-supported art against non-conformist practices.  This is particularly manifest in the exhibition’s second “constellation” of documents, “From People’s Education to the Democratization of Art. The Neo-avant-garde Artist as Educator of [the] People”, which addressed the educational role of art in a region, Eastern Europe, where the state alone was responsible for education. Artistic situations or activities proposed by ?ubomír ?ur?ek, Dóra Maurer, Orshi Drozdik, Anna Kutera, KwieKulik and Grupa 143, with the participation of colleagues, students, amateurs, passers-by, etc. in a wide range of contexts directly questioned the social role of art and artists, developing utopian and emancipatory tools for engaging with social reality and refuting in the process the idea of art in Eastern Europe as being fully disconnected from the official sphere. For instance, if the situation of Czechoslovakia during the years of “normalization” was less favorable to art’s interaction with the official sphere, there were still opportunities if not for a truly equal dialogue between these two realms, then at least for their mutual tacit acceptance; in this context, ?ubomír ?ur?eks’ experiences as a designer of cultural and social centers in Bratislava (Psychological Environment, 1977) as well as a public art school teacher (Message IV, 1982), are particularly revealing as instances of didactic exchange with the audience in an institutional context.(See: Mira Keratová, ?ubomir ?ur?ek. Situational Models of Communication, Slovak National Gallery, 2013.)

This is particularly manifest in the exhibition’s second “constellation” of documents, “From People’s Education to the Democratization of Art. The Neo-avant-garde Artist as Educator of [the] People”, which addressed the educational role of art in a region, Eastern Europe, where the state alone was responsible for education. Artistic situations or activities proposed by ?ubomír ?ur?ek, Dóra Maurer, Orshi Drozdik, Anna Kutera, KwieKulik and Grupa 143, with the participation of colleagues, students, amateurs, passers-by, etc. in a wide range of contexts directly questioned the social role of art and artists, developing utopian and emancipatory tools for engaging with social reality and refuting in the process the idea of art in Eastern Europe as being fully disconnected from the official sphere. For instance, if the situation of Czechoslovakia during the years of “normalization” was less favorable to art’s interaction with the official sphere, there were still opportunities if not for a truly equal dialogue between these two realms, then at least for their mutual tacit acceptance; in this context, ?ubomír ?ur?eks’ experiences as a designer of cultural and social centers in Bratislava (Psychological Environment, 1977) as well as a public art school teacher (Message IV, 1982), are particularly revealing as instances of didactic exchange with the audience in an institutional context.(See: Mira Keratová, ?ubomir ?ur?ek. Situational Models of Communication, Slovak National Gallery, 2013.)

The second constellation also raises the crucial issue of artists’ professional status and working conditions in a Socialist system. In most cases, the artist was situated between the national Artists Union that provided his or her an officially recognized position as an artist, on the one hand, and all types of non-art related jobs that allowed him or her to make a living, on the other. Should this situation be considered by definition schizophrenic and frustrating? Far from idealizing the conditions numerous art practitioners had to cope with if they wanted to avoid loosing their job and leaving their country–to mention only two from a large list of possible punishments–, examples such as Dóra Maurer’s Creativity Exercises (carried out with Miklós Erdély at the Ganz-Mávag factory’s cultural center in Budapest, 1975-77), and KwieKulik’s film Activities (1972) that documents four day of collective creation in the studio of Polish National TV, confirm that crucial artistic experiments could take place in state-runspaces and organizations during the 1970-80s. Despite the apparent rigidity of official structures, and instead of criticizing or threatening the socialist utopia, creative participatory practices acted as an emancipating tool that supported – voluntarily or not – the state’s educational project in venues such as local cultural centers, amateur circles, and secondary schools. The case of Yugoslavia is particularly significant here, since state-supported cultural organizations like the Students Cultural Centers were amongst the most important places where avant-garde practices and ideas were developed, and claims for art’s autonomy had a direct resonance with the principles of workers’ self-management, a pillar of the Yugoslav state’s official policy.(The counter-exhibition Oktobar 75 (Students Cultural Center, Belgrade, 1975) illustrates the complex positioning of cultural workers regarding the question of self-managing art. See Jelena Vesi?, “Oktobar 75 – An Example of Counter-Exhibition (Statement on Artistic Autonomy, Self-Management and Self-Critique)”, in Parallel Chronologies online, http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/oktobar-1975/ (Last accessed 16 March 2017). See also Zorana Doji? and Jelena Vesi? (eds.), Policital Practices of (Post-) Yugoslav Art (Belgrade: Prelom, 2010).)

Of course, one of the pitfalls of seeing the artist as a catalyst of progressive social and educational initiatives, as this exhibition does, is to produce a new radical label that might promptly be recuperated by the neoliberal system of evaluation. Sitting Together successfully avoids such a reductive vision as it based its display and narrative on a back and forth – or oscillatory movement – that engages with a variety of scales, formats and temporalities.

Of course, one of the pitfalls of seeing the artist as a catalyst of progressive social and educational initiatives, as this exhibition does, is to produce a new radical label that might promptly be recuperated by the neoliberal system of evaluation. Sitting Together successfully avoids such a reductive vision as it based its display and narrative on a back and forth – or oscillatory movement – that engages with a variety of scales, formats and temporalities.

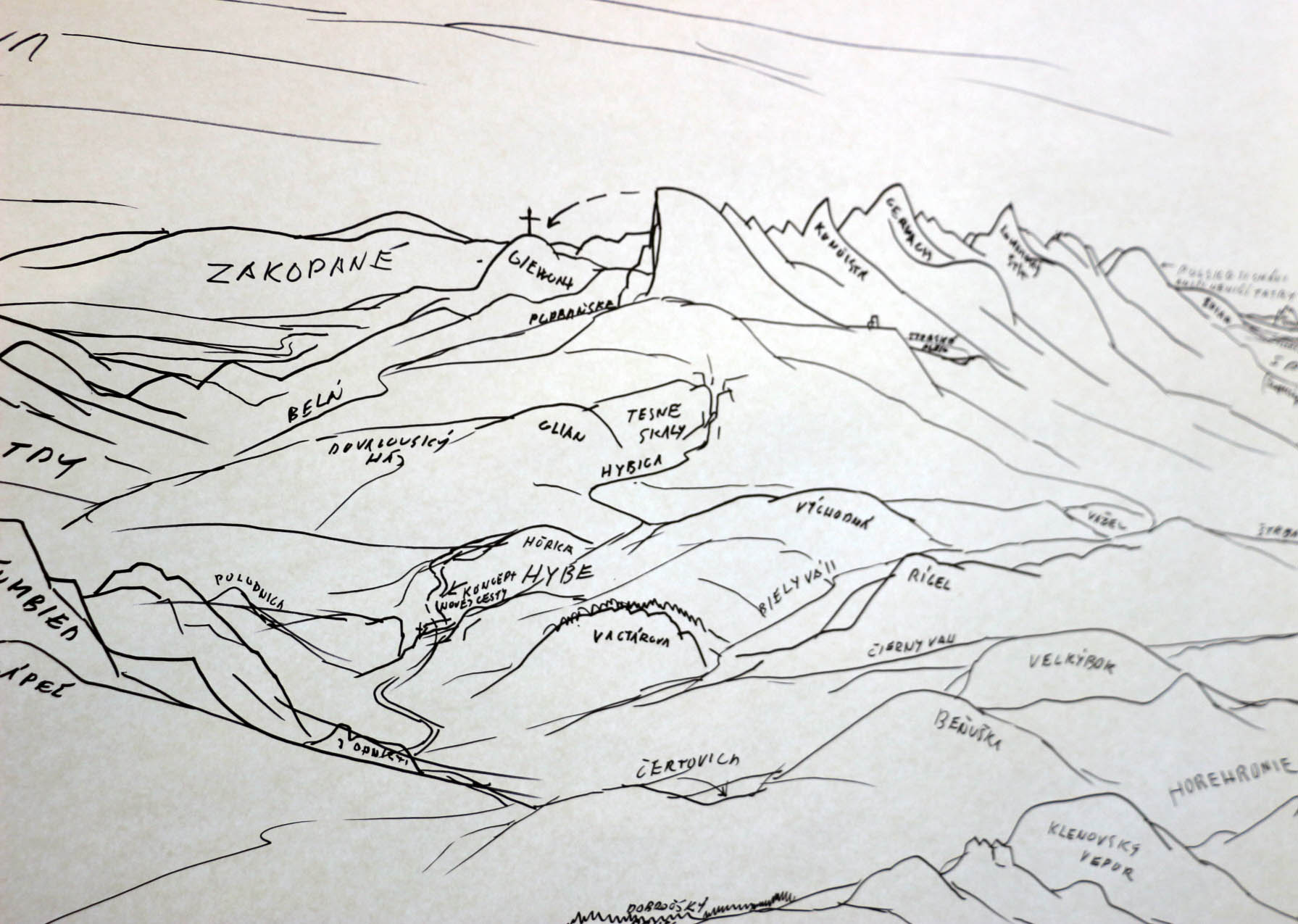

The third constellation of documents, entitled “Methodologies of Historization,”(In the texts surrounding the exhibition, the term “historization” is preferred to “historicization.” On historicization, see also the Glossary of Common Knowledge developed by the Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana, and the confederation including six European art institutions L’Internationale, http://glossary.mg-lj.si/referential-fields/historicization (Last accessed 16 March 2017).) contemplates artistic practices and events of the 1970s from the perspective of their present readings and interpretations.The pieces on display address the lacks and absences inherent in the memory of past events and show different attempts of reconstructing them: Petra Feriancová’s speculative and sensible research around Grazing a Lamb, as it translates into the installation and publication; the video recording of the cross-generational “Potlatch of Archives” where artists and curators conversed freely about artifacts and memories , as well as Peter Bartoš’ impressive one-piece drawing, a spectacular map in which traditional topographic elements coexist with Bartoš’ personal memories of places.(The Potlatch of Archives was organized by Petra Feriancová and Zsuzsa László on September 12, 2016, with the participation of László Beke, Peter Bartoš, ?ubomir ?ur?ek, Daniel Grún, Kv?ta Fulierová, Mira Keratová and Rudolf Sikora.) Realized during the exhibition’s set up, the map acts as a kind of background (this term was suggested by Zsuzsa Laszlo) for the works gathered in this third constellation. Finally, as another narrative thread spatially disseminated in the exhibition, László Beke’s handwritten comments remind us that first-hand testimonials still take a crucial part in unfolding and transmitting these stories.

Petra Feriancová’s speculative and sensible research around Grazing a Lamb, as it translates into the installation and publication; the video recording of the cross-generational “Potlatch of Archives” where artists and curators conversed freely about artifacts and memories , as well as Peter Bartoš’ impressive one-piece drawing, a spectacular map in which traditional topographic elements coexist with Bartoš’ personal memories of places.(The Potlatch of Archives was organized by Petra Feriancová and Zsuzsa László on September 12, 2016, with the participation of László Beke, Peter Bartoš, ?ubomir ?ur?ek, Daniel Grún, Kv?ta Fulierová, Mira Keratová and Rudolf Sikora.) Realized during the exhibition’s set up, the map acts as a kind of background (this term was suggested by Zsuzsa Laszlo) for the works gathered in this third constellation. Finally, as another narrative thread spatially disseminated in the exhibition, László Beke’s handwritten comments remind us that first-hand testimonials still take a crucial part in unfolding and transmitting these stories.

In an oscillating movement between practices and events from the 1970s and their examination from actual perspectives, Sitting Together not only raises the issue of how exhibitions, meetings, and participatory works from the 1970s and early ’80s in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia can be addressed today, it also relates to them from a non-orthodox perspective that challenges linear curatorial and historiographic schemes. The show’s effort to elaborate intersectional readings of different ranges of art activities, temporalities, and forms of participation opens a space for thinking these activities alongside their consequences and reverberations.