Hungary in Focus: Conservative Politics and Its Impact on the Arts. A Forum

In 2003, Hedvig Turai, Allan Siegel and I put together an overview of diverse aspects of the Hungarian art scene. What gave urgency to providing an update so soon is that within just a few years, the cultural landscape has undergone significant change. Fidesz, the conservative right-wing party, has been in power for three years now in Hungary, gradually transforming the country into an isolationist, ethno-nationalist, authoritarian state not unlike Russia.

Concerning the post-Cold War world, Jürgen Habermas’s notion of a “post-national constellation” seems to be an outcome of wishful thinking, since despite the recurring prognosis of the death of nations and nationalism in our globalized world, the oppressors have returned with a vengeance and with updated, invigorated methods. Thus, the problems of nationalism and ethnic conflicts are not gone–as was expected with the end of the bloody Balkan wars–they just appear in different forms, or rather they have many faces and do not come in a one-size-fits-all format. Nationalism cannot be located exclusively in the post-socialist countries. It is also apparent in Europe’s modern democratic welfare countries, such as France, Denmark and Finland, and even appears in the most multicultural and open-minded countries, such as the Netherlands. One could say that today the specter of nationalism is haunting Europe. The trajectory and scale might be very different, but the imminent danger of its aim is to restage societies along idealized, homogenous conceptions of the nation as a means to cope with the fear and insecurity of global financial capitalism. Nationalism thrives towards hegemony and, thus, aims to control all fields of society, including culture and art. As Marita Muukkonen puts it “a hegemony is always characterized by the need to keep the codes’ exclusive translation to itself, to restrict all interpretation to a single meaning, if necessary by force (all totalitarianism, all fundamentalism), thus effectively, and violently, putting a stop to communication.”

Our case study of Hungary, presented via a series of podcast interviews with various cultural players, can be regarded as a close examination of the process of aggressive invasion of the nation-state into the field of culture and art in a country on the extreme pole of post-socialist nationalisms. Since 2010, Fidesz (which holds a two-thirds majority in Parliament) has authoritatively transformed the social, economic and cultural fields, assuring state control over all segments of society through changes in the legislative system, centralizing institutional structures, replacing professional officials with party commissars and, at the same time, eliminating democratic accountability and participation. Following different segments of society — the media, education, health care, and social welfare — the invasion has recently reached culture, including the film industry, theater, cultural heritage and the visual arts. Since the complete survey of the cultural field is beyond our scope, this introduction and the following podcasts focus exclusively on the visual arts, their institutional changes and stakeholders.

I will sketch out the recent condition of culture and cultural policymaking, providing a framework and background to the podcasts, the references to which will be woven into the text. Giving voice to as many active agents of the scene as possible was a conscious decision. Thus, twelve art professionals will speak about the state of Hungarian culture, sharing their knowledge, opinion and personal feelings about different aspects of the issues at hand.

As for the factual changes: In 1992, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS) founded the Széchenyi Academy of Arts and Literature for prominent representatives of those fields not included in HAS after 1949, and was provided with 12 million HUF (Hungarian forint). In the same year, a counter institution, the Hungarian Art Academy (MMA), a civil, private fraternity of close friends, was founded by twenty-two right-wing, ultraconservative artists. In 2011, the Hungarian Parliament voted for a New Constitution (Basic Law) that took effect on January 1, 2012. A particular article was included, by which MMA was registered into the Basic Law and was legally elevated to the status of a public body supplied with 2.4 billion HUF. Thus, a kind of shadow ministry was established. As a result, MMA now has full power and authority to decide and administer public duties of art and culture (financial, education, Hungarian representation abroad). It is also in charge of auditing the resources of the National Cultural Fund. As for its vision, it has an ambition to define the national canon. Its president, György Fekete, an interior designer with a dubious past and aggressive, anti-democratic rhetoric, declares clearly that “works reflecting a Christian-Nationalist ideology will be given priority when state subsidies are paid out.” He demands that in the “culture of the nation” the trends, movements, ideas of the “national culture” be positively discriminated. Among the conditions for applying for membership is a clear national commitment.

Against the empowerment of MMA, the grass-roots organization Free Artists was formed, whose first action, an intrusion into the first meeting of MMA members, sparked the civic movement in the otherwise apolitical sphere of visual arts in Hungary. The group protested against the conservative takeover of the MMA, against a situation in which there is no dialog, against the routine whereby officials in charge of important institutions are replaced by commissars, and against the exclusionary practice of MMA. Free Artists also demand autonomy. They started the NEMMA blog, the name of which means No to MMA.

PODCAST #1: Activism and Artistic Strategies

PODCAST #1: Activism and Artistic Strategies

In this interview, artists Csaba Nemes and Szabolcs KissPál, leading members of the Free Artists group, speak to Drs. Maja and Reuben Fowkes, of the Translocal Institute, about the challenges posed by controversial government policies towards the arts in Hungary. Nemes and Kisspál also share how they see the contemporary art scene evolving in the future. (link to podcast).

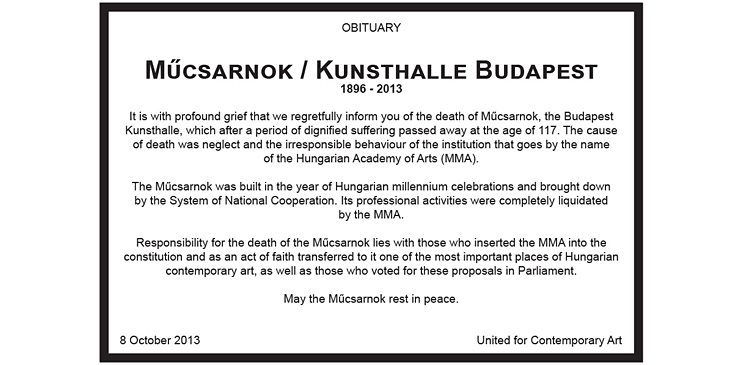

In November 2012, and effective from 2013, a government resolution proclaimed the building of the Kunsthalle M?csarnok, one of the main institutions of contemporary art, as a real-estate holding of the MMA. MMA obtained not only proprietary rights over the building of the M?csarnok, but also has the right of confirmation over anything that happens within building. What this means exactly, and how it will work on an everyday basis, is still an open question. Demonstrating against the invasion of an independent art institution by party politics, young curators have initiated exhibitions held regularly outside of the Kunsthalle, named Outer Space Projects. (In the interview conducted by Eszter Szakács, curator Márton Pacsika introduces this initiative.)

Already the field of art is being centralized, and comrades who are loyal to the regime and whose ideas are in total compliance with the vision promoted by the government are being placed in chief cultural positions. The advantage of such a practice is that an official who is selected to lead an institution is close and loyal to the ruling party. There is then no further need for official censorship, since this process automatically guarantees the proper ideological content.

László Baán, the power-hungry managerial director of the Museum of Fine Arts, proved to be the main partner in the extravagant and megalomaniac visions of the regime. His leadership, as defined rightly by one critic, is closer to a producer than to an art professional. He is the commissar of one of the most ambitious dreams of the Budapest “Museum Quartier” that is to be realized in Heroes Square from not-yet-existing EU money, a huge conglomerate in which all the main museums (so far, the Hungarian National Gallery, the Ludwig Museum, and the Photography Museum) would be merged. The first step has already been taken, the annexing of the Hungarian National Gallery by the Museum of Fine Arts, despite protests and without any kind of professional groundwork or consultation with the representatives of professional organizations.

Appointing non-professional actors into the leadership of high-rank art institutions continued with Gábor Gulyás, who was handpicked and directly appointed to the directorial position of M?csarnok Kunsthalle after an open tender was neglected. Such anomalies continued with the Ludwig Museum, when the five-year contract of director Barnabás Bencsik expired on Feb. 28, 2013. The invitation to tender was sent out only after his contract expired, thus from that date the museum operated without professional leadership. Two applications were filed: one, sixty pages, elaborated upon the application submitted by the ex-director, whose activity was very successful and supported by the art field and by the Ludwig Foundation; the other, a sixteen-page application with only general ideas and lacking any specifics, was submitted by Júlia Fabényi. While Bencsik’s application was immediately available for the public, the other candidate did not go public with her proposal. The majority of the jury was recruited from employees of the ministry and the process was carried out behind closed doors. There was no discussion, and the voting machine fulfilled the expectations by voting for Fabényi, who is close to and has the full confidence of the party.

PODCAST #2: Activated Roles of Curating in Hungary

PODCAST #2: Activated Roles of Curating in Hungary

In this interview, Eszter Szakács, a young Hungarian curator, interviews three curators, of different generations, working in Hungary: Hajnalka Somogyi, Adele Eisenstein, and Márton Pacsika. These discussions explore recent changes within the cultural policy of the Hungarian government and, more specifically, how they affect curatorial work. (link to podcast).

In response to these various political moves, the grassroots organization United for Contemporary Art was created by transit.hu, which operates on the principles of basic democracy and who occupied the stairs of the Ludwig Museum. The occupiers demanded complete transparency in the selection process, and autonomy for cultural institutions, as well as dialog with professionals in the field. The hard-core occupiers were sitting, eating, sleeping on the stairs, constantly organizing meetings and professional events. Despite their civic protest, in which acknowledged artists, art historians, curators and students took part, it was totally ignored and the officials appointed Fabényi as director of the Ludwig Museum.

PODCAST #3: Occupying the Ludwig Museum

PODCAST #3: Occupying the Ludwig Museum

In this interview, curator and critic Gyula Muskovics speaks with Dóra Hegyi, project leader of tranzit.hu, on the occasion of the occupy action that took place on the stairs of the Ludwig Museum in Budapest May 9-21, 2013. Hegyi, who took part in the action, speaks about its origins and the newly formed civic group United for Contemporary Art. (link to podcast).

There is a debate going on in intellectual circles as to whether or not such a thing as cultural politics exists in contemporary Hungary, and whether the ongoing aggressive measures in the field of culture are driven by fear, strength, or ignorance. There are, however, a lot of signs that indicate a comprehensive system is behind the seemingly random and not always understandable official actions taken by the regime. For example, the latest thematic issue of the magazine National Interest: Thinking in Strategies For the Nation, not available in press kiosks but disseminated privately to party comrades, apparatchik and other insiders, is dedicated to cultural politics. According to one of its agenda-setting articles, “The ruling right wing government is committed to such a cultural politics which supports not a vocational politics (politics operated by professionals) but rather that kind which intends to push the Hungarians upwards in terms of the vision of a strong Hungary.” For the agents of official policymaking, influencing the direction of high culture is necessary and unavoidable, since the previous Socialist regime excluded and marginalized art labeled as traditionalist, post-romanticist, and isolationist or, in other words, they excluded national voices. So now, these conservative strains in art are being supported.

The rhetoric of Fidesz is based on the idea that the previous government did not accomplish true political transition. The socialist period is regarded as illegitimate, so the current administration continues political threads from 1944, as if such a symbolic gesture would erase the period of socialism and rewrite history. Thus, all the monuments connected to the democratic, liberal or slightly leftist tradition are falling victim to this second wave of purification. Hungarians are taking part in a mental time travel back to the interwar period, flavored by the oppressive methods of the Communist fifties. The goal of the current government is to build a strong national state, as opposed to the long-outlived socialist state, and culture is conceived as part of this nation building.

The culture that is supported financially and institutionally in Hungary today is one that holds national, traditional and Christian values. Advanced contemporary art and culture, with its international and critical nature, doesn’t fit into the conception of a strong nation-state. Instead, the “folk art industry” (traditional native culture and popular folk art) is fully supported and receives overwhelming amounts of funding, despite the economic crisis. The selective memory of the officials remembers only successful events in Hungarian history. By contrast, its failures as well as instances that call for self-responsibility are not included in their memory work. In other words, remembering, to them, is about handpicking those elements from history that are well liked, while pushing into oblivion those that are disturbing or controversial. The point is not to work through the traumas, but rather to lick the wounds, so to say.

The culture that is supported financially and institutionally in Hungary today is one that holds national, traditional and Christian values. Advanced contemporary art and culture, with its international and critical nature, doesn’t fit into the conception of a strong nation-state. Instead, the “folk art industry” (traditional native culture and popular folk art) is fully supported and receives overwhelming amounts of funding, despite the economic crisis. The selective memory of the officials remembers only successful events in Hungarian history. By contrast, its failures as well as instances that call for self-responsibility are not included in their memory work. In other words, remembering, to them, is about handpicking those elements from history that are well liked, while pushing into oblivion those that are disturbing or controversial. The point is not to work through the traumas, but rather to lick the wounds, so to say.

PODCAST #4: Cultural Perspectives: A Wider View

In this interview, Hedvig Turai, co-editor of this update, talks with Gergely Nagy, art critic and journalist, about cultural politics. Nagy discusses the “big picture,” mapping the current political situation, and drawing a trajectory of some of the events outlined in this introduction. (link to podcast).

Unfortunately, the protest movements mentioned here have not achieved any real results, and the process for centralizing and controlling the scene described above and discussed in the podcasts is ongoing. However, the internal debates continue, as does the search for alternative forums and institutions outside of the control of current state institutions that are busy launching a new national canon on the ruins of socialism.