Tactics for the Here and Now: The 5th International Bucharest Biennial for Contemporary Art

TACTICS FOR THE HERE AND NOW: THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL BUCHAREST BIENNIAL FOR CONTEMPORARY ART, VARIOUS LOCATIONS, MAY 25 – JULY 22, 2012

How can an art biennale take a renewed critical stance towards its own immersion in the production of cognition, and in the effects of accelerated semiocapitalism, or the capitalization of linguistic labor (to which the critical discourse of contemporary art certainly belongs)?Franco Berardi Bifo, Precarious Rhapsody. Semiocapitalism and the Pathologies of the Post-Alpha Generation (Minor Compositions, London), 2009, pp. 44-49. Tackling the broad topic of the precariousness of contemporary living – or radical instability, loosely defined in relation to the changing cultural and socio-economic conditions of both life and artistic practice – the 5th International Bucharest Biennial for Contemporary Art, curated by Anne Barlow, focuses on investigative artworks, gathering together nineteen projects of artistic research, complemented by various small-scale parallel events. Of these, only two projects were conceived by Romanian artists and around half by artists living and working mostly in Europe. According to the curatorial statement, the selected works are able to produce new forms of knowledge (albeit regarded as “networks of indiscipline, lines of flight and utopian questionings”)Simon Sheikh “Talk Value: Cultural Industry and the Knowledge Economy,” in On Knowledge Production, eds. Maria Hlavajova, Jill Winder and Binna Choi (Utrecht and Rotterdam, 2008), p. 196, as quoted in Anne Barlow, “Tactics for the Here and Now,” in Pavilion, no. 16 (2012), p. 7. through their patient investment with the shifting structures of social and historical reality and their rapidly changing appearances. This may provoke ”a deceleration of intellectual labor and cognitive activity offered by art,” i.e. a focus on ”the creation of a deeper slower and intensified time” in the artistic experience of the work.Sotirios Bahtsetzis, ”Eikonomia: Notes on the Economy and the Labor of Art,” in Pavilion, no. 16 (2012), p. 49.

Although such an approach may be taken and is often expected to mean a research of local conditions, the only noticeable relation to the locality of the Bucharest Biennial lies in the spatial articulation of the exhibition as a gesture, if not, on a more abstract scale, in the precarious condition of Romanian democracy,the fragile constitution of its public space and the precariousness of its institutional structures, whose material embodiments still bear witness to its post-socialist condition. Thus, the discursive positioning of the Biennial as it is articulated by the curator of this edition becomes manifest. It attempts to connect a local, hence, particular understanding of Romania’s socio-political life to other situations of precariousness, shared in a world connected through the poetic use of the faculty of political imagination (if such a Kantian invention may be granted), rather than to investigate its own position in terms of the politics of identity and representation.

Although not obvious at first, such a statement gains in significance if interpreted in the context of the history of Romanian institutional construction. The Bucharest Biennial is the second largest event of contemporary art after the Periferic Biennale, for many years a leading critical event focusing on the borderline condition of the host city of Ia?i, both in terms of its peripheral location on the map of Europe and its complex post-socialist historicity. In the light of the last two editions, the Bucharest Biennial seems to have repositioned itself by strategically connecting the city’s political past and present with discourses that are resonant with but not always consonant to it. Thus, it confesses a timely and more appropriate understanding of locality, which frames the context not in terms of a given set of material conditions but as a loosely connected situational topography.

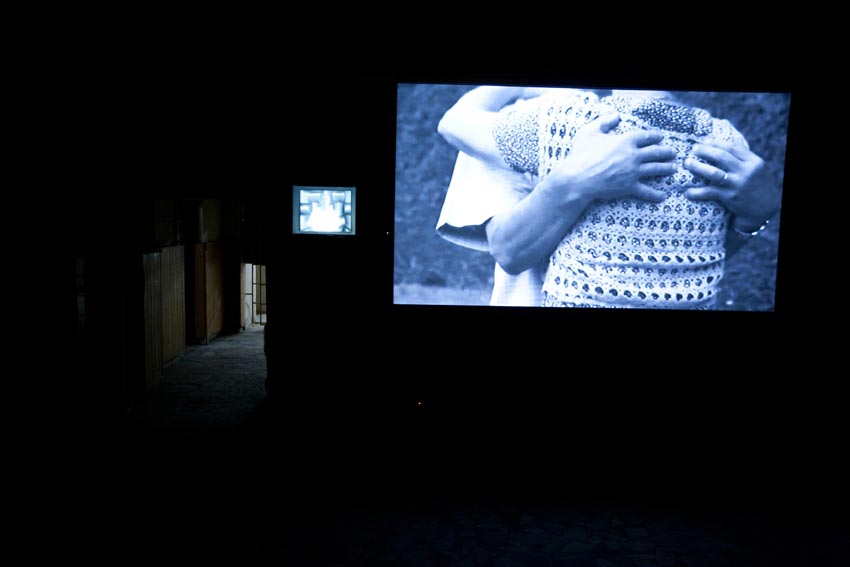

As curator, Barlow assumed the tactics of discrete inquiry instead of bold statements, choosing a handful of very different artworks, most endowed with a fine-grained aesthetic and conceptual accuracy, but whose only commonality lies in their ability to articulate contemporaneity as an actual field of interrogation and to produce a “decelerated” experience of meaning production. It succeeds to present a collection of artistic singularities, imprecise and unique in their methodologies for reshaping subjectivity, whose only problem lies in the discrete voice of the collection itself. For example, the exhibition’s discrete presence in the everyday life of the city, with works situated in the basements, corridors, and deserted halls of the House of the Free Press, the former building of the communist propaganda newspaper Scânteia (The Spark), and the Institute for Political Research, was able, at best, to stir the political imaginary of the viewer, avowing for the impossibility to implement artistic tactics on a broader social scale. In other words, any potential revolutionary impetus was annihilated, since the articulation of political transformations was to be produced through the aesthetic dimension of art rather than through the use of art as a platform for political protest – including poetical practices of personal rather than collective subjectivation. The works’ discrete presence, silent within a loud cacophony of voices, was unable to consistently disrupt the political mechanisms inherent to their sites.

Such impressions are supported by the scattered physical locations of the Biennale, spread across the city in small institutions, including popular places of entertainment, such as the Union cinema, which screened Aurelien Froment’s Pulmo Marina that intended to displace the ordinary

Such impressions are supported by the scattered physical locations of the Biennale, spread across the city in small institutions, including popular places of entertainment, such as the Union cinema, which screened Aurelien Froment’s Pulmo Marina that intended to displace the ordinary  patterns of consumption of the cinematic image, and the small restaurant Nana, host to Ruth Ewan’s A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World. Other artworks appeared as inserts within the ideological circuits of various publications, such as the women’s magazine Tabu, the architecture magazine Zeppelin and Vice, the magazine of “radical lifestyle.” Few artworks appear in contemporary art galleries. Instead, they occupy the spaces of Unicredit Pavilion and Alert Studio, an artist-run space that fosters educational programs as an alternativeto the activities promoted by the National University of Arts from Bucharest. Other works were exhibited in community cultural centers, such as Make a Point, situated inside a former communist textile factory located in a poor neighborhood of Bucharest. Some of these pieces, such as Harris Epaminonda’s Polaroid series exhibited at Alert Studio, reflected upon critical visual pedagogy.

patterns of consumption of the cinematic image, and the small restaurant Nana, host to Ruth Ewan’s A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World. Other artworks appeared as inserts within the ideological circuits of various publications, such as the women’s magazine Tabu, the architecture magazine Zeppelin and Vice, the magazine of “radical lifestyle.” Few artworks appear in contemporary art galleries. Instead, they occupy the spaces of Unicredit Pavilion and Alert Studio, an artist-run space that fosters educational programs as an alternativeto the activities promoted by the National University of Arts from Bucharest. Other works were exhibited in community cultural centers, such as Make a Point, situated inside a former communist textile factory located in a poor neighborhood of Bucharest. Some of these pieces, such as Harris Epaminonda’s Polaroid series exhibited at Alert Studio, reflected upon critical visual pedagogy.

Each location connects the works it hosts to the history and significance of site, adding to the overall quality of the exhibition as a discursive practice concerned with the articulation of immaterial labor. On the other hand, the scattered appearance of the Biennale, perhaps expected to “construct rather than contemplate situations,”R?zvan Ion, from “Contemplating to Constructing Situations,” in Pavilion, no. 16 (2012), pp. 28-33. gave the impression that the event actually ignored its local audience who seemed unaware of the very existence of the exhibitions, despite best intentions to intervene in places suitable and well chosen for the specific pieces installed there. The difficulty of reaching the locations (doubled by a sometimes defective organization, such as the temporary absence of work in the Nana restaurant due to some technical problems), transformed the experience of the Biennale into a process of investigation, fortunately well off the city’s typical touristic venues but ultimately confined to the small circles of the art world.

Each location connects the works it hosts to the history and significance of site, adding to the overall quality of the exhibition as a discursive practice concerned with the articulation of immaterial labor. On the other hand, the scattered appearance of the Biennale, perhaps expected to “construct rather than contemplate situations,”R?zvan Ion, from “Contemplating to Constructing Situations,” in Pavilion, no. 16 (2012), pp. 28-33. gave the impression that the event actually ignored its local audience who seemed unaware of the very existence of the exhibitions, despite best intentions to intervene in places suitable and well chosen for the specific pieces installed there. The difficulty of reaching the locations (doubled by a sometimes defective organization, such as the temporary absence of work in the Nana restaurant due to some technical problems), transformed the experience of the Biennale into a process of investigation, fortunately well off the city’s typical touristic venues but ultimately confined to the small circles of the art world.

For instance, Ciprian Homorodean’s Take the Book, Take the Money, Run!, installed in the Institute for Political Research, presents a user’s guide to stealing, an educational tool whose engagement with the precariousness of labor in times of financial crisis is cunningly straightforward. Marina Albu’s The Real House of People recreates the experience of lights going out during communist times, the relevance of which today lies in its ability to propose an interruption, a suspension of history, a pause for reflection and, perhaps, a communitarian dialogue amidst the flow of everyday activities. The physical setting of the work, filled with oil lamps and candles and their heavy smells, is reminiscent of both a church and a funeral, recontextualizing collective histories of communism into a personal narrative that one listened to using headphones. Anahita Razmi’s video installation Roof Piece Tehran re-enacts choreography performed by Trisha Brown on New York’s rooftops in the 1970s within the oppressive political context of today’s Islamic world. Thus, Brown’s original allegory of alienation becomes a poetical manifesto against oppression everywhere.

Personal and collective strategies of representation and communication seem to become a favorite topic of artistic research and aesthetic intervention. The artworks exhibited in the Unicredit Pavilion engage with both structures of political imagination and strategies of visual and textual representation through tactics of fictionalization and poetic communication, operating mostly on a personal level. For instance, Rinus van de Velde’s drawings (Untitled – The Last Bishop) retell the story of Bobby Fischer and Boris Spasski’s chess game played in the 1972 World Championship through an exercise of imaginary impersonation, the artist himself taking the place of Fischer’s character and projecting his own existential anxieties and artistic reflections. Thus, the piece becomes a metaphor for the practice of studio art in contemporary times and engages a reflection of its own position in the political and cultural field. In turn, Alexander Singh’s The Pledge – Simon Fujiwara consisting of forty framed images elaborates both a mental cartography and a visual portrait of the performer Simon Fujiwara as the result of a conversation between the two artists. The visual manipulation of verbal communication explores the gap between reality and fiction and between different systems of representation and understanding.

Personal and collective strategies of representation and communication seem to become a favorite topic of artistic research and aesthetic intervention. The artworks exhibited in the Unicredit Pavilion engage with both structures of political imagination and strategies of visual and textual representation through tactics of fictionalization and poetic communication, operating mostly on a personal level. For instance, Rinus van de Velde’s drawings (Untitled – The Last Bishop) retell the story of Bobby Fischer and Boris Spasski’s chess game played in the 1972 World Championship through an exercise of imaginary impersonation, the artist himself taking the place of Fischer’s character and projecting his own existential anxieties and artistic reflections. Thus, the piece becomes a metaphor for the practice of studio art in contemporary times and engages a reflection of its own position in the political and cultural field. In turn, Alexander Singh’s The Pledge – Simon Fujiwara consisting of forty framed images elaborates both a mental cartography and a visual portrait of the performer Simon Fujiwara as the result of a conversation between the two artists. The visual manipulation of verbal communication explores the gap between reality and fiction and between different systems of representation and understanding.

Pieces installed in the House of the Free Press exemplify tactical procedures of investigation connected to collective structures and devices of mediation and representation Their installation activates the enormous potential of the building as a condensed and saturated signifier and as a location articulating a defamiliarizing and profoundly somatic experience of space. Wandering through the long corridors of the printing house in the dim-lit basements of this huge building, the pregnant smell of ink accompanies the viewer in search for the artworks distributed inlarge, empty spaces where now broken printing machines used to work. The present-day material condition of the former House of Propaganda condenses post-communist history as a labyrinth, a dystopic ruin, and a reminder of the often neglected connection between immaterial production and manual labor.

Except for the above-mentioned generic connection with institutions and practices of representation and mediation, the relation between the selected artworks installed here is not straightforward. Neither is their relation with the multiple meanings of the location. David Malikovic’s two-channel video Out of Projection, a fictional and allegorical commentary on the conditions of industrial labor, connects past and future, resonating immediately to the situation of former workers in the machinery of communist press and to the precarious condition of labor in post-socialist countries. Engaging with the documentary form, Malikovic also connects the futurist dimension of the socialist modernist imaginary with nostalgic recollections of the past, thus exploring the “off-modern” tracks of the socialist project and the remains of its utopia today. Marina Naprushkina’s Office for Anti-Propaganda investigates dictatorial procedures in present-day communist Belarus, echoing the ideological apparatus of authoritarian power and its repressive mechanisms during Ceaucescu’s regime.

Except for the above-mentioned generic connection with institutions and practices of representation and mediation, the relation between the selected artworks installed here is not straightforward. Neither is their relation with the multiple meanings of the location. David Malikovic’s two-channel video Out of Projection, a fictional and allegorical commentary on the conditions of industrial labor, connects past and future, resonating immediately to the situation of former workers in the machinery of communist press and to the precarious condition of labor in post-socialist countries. Engaging with the documentary form, Malikovic also connects the futurist dimension of the socialist modernist imaginary with nostalgic recollections of the past, thus exploring the “off-modern” tracks of the socialist project and the remains of its utopia today. Marina Naprushkina’s Office for Anti-Propaganda investigates dictatorial procedures in present-day communist Belarus, echoing the ideological apparatus of authoritarian power and its repressive mechanisms during Ceaucescu’s regime.

Jill Magid’s interventions in the magazines Tabu and Zeppelin also presented in a hall of the House of the Free Press disrupt the act of reading and the mechanisms of passive consumption, obliquely and critically engaging the ideology of the press and images of the war on terrorism as constructed in media. Vesna Pavlovic’s investigation into the latent politics of tourist photography also read as a larger interrogation on the mediation of cultural experience and the politics of representation. Her The Search for Landscapes revolves around the framing and capturing of images and the uncertainty of the documentary potential of photography in relation to its distribution in the press, conceived not only as the production of presence (by assigning significance to the momentary), but also as a fleeting archival practice.

Jill Magid’s interventions in the magazines Tabu and Zeppelin also presented in a hall of the House of the Free Press disrupt the act of reading and the mechanisms of passive consumption, obliquely and critically engaging the ideology of the press and images of the war on terrorism as constructed in media. Vesna Pavlovic’s investigation into the latent politics of tourist photography also read as a larger interrogation on the mediation of cultural experience and the politics of representation. Her The Search for Landscapes revolves around the framing and capturing of images and the uncertainty of the documentary potential of photography in relation to its distribution in the press, conceived not only as the production of presence (by assigning significance to the momentary), but also as a fleeting archival practice.

Over all, the exhibition succeeded in challenging routines of certainty, time, and the consumption of meaning, and in performing a politics of unknowing by means of small, almost imperceptible yet destabilizing gestures. However, it is debatable whether such tactics are able to produce new forms of knowledge beyond the autonomous structure of the art world and for whom they may apply. This situation may be formulated as an aporia: a reflexive form of participation requires interpretive abilities often beyond the capabilities of a large and local audience, while a sustained educational program accompanying the biennale would have attenuated the disruptive cognitive effect of the works themselves. It is also obvious that such a production will not become a publicly affordable instrument for collective re-subjectivation beyond the Biennale itself. To what extent, then, are such tactics of unknowing actually the unforeseeable alteration of a knowledge that we already posses, and to what extent may they be reproduced and replicated in conditions of constant cultural translation?

Over all, the exhibition succeeded in challenging routines of certainty, time, and the consumption of meaning, and in performing a politics of unknowing by means of small, almost imperceptible yet destabilizing gestures. However, it is debatable whether such tactics are able to produce new forms of knowledge beyond the autonomous structure of the art world and for whom they may apply. This situation may be formulated as an aporia: a reflexive form of participation requires interpretive abilities often beyond the capabilities of a large and local audience, while a sustained educational program accompanying the biennale would have attenuated the disruptive cognitive effect of the works themselves. It is also obvious that such a production will not become a publicly affordable instrument for collective re-subjectivation beyond the Biennale itself. To what extent, then, are such tactics of unknowing actually the unforeseeable alteration of a knowledge that we already posses, and to what extent may they be reproduced and replicated in conditions of constant cultural translation?

Such interrogations lead to what may represent, in my opinion, the key question raised by this, otherwise, smart biennial: To what extent is the idea of altering the existing political imaginary and opening up the existing microstructure of present-day semiocapitalist society not just another emancipating utopia of artistic autonomy that, ultimately, leaves untouched the power structures the artworks loosely relate to (whether the media, the entertainment industry, educational mechanisms, state politics, or the networks of production, distribution and consumption of art) and their inherent “distribution of the sensible”?

Cristian Nae is a Romanian art critic and theorist. He is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Arts in Iasi and a GETTY-NEC fellow of the New Europe College in Bucharest. He is former editor of Vector Magazine, and has regularly published art criticism for art magazines such as IDEA or ARTA, as well as research articles in various journals, collective volumes and exhibition catalogues on topics related to contemporary art history, aesthetics and cultural studies.

Cristian Nae is a Romanian art critic and theorist. He is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Arts in Iasi and a GETTY-NEC fellow of the New Europe College in Bucharest. He is former editor of Vector Magazine, and has regularly published art criticism for art magazines such as IDEA or ARTA, as well as research articles in various journals, collective volumes and exhibition catalogues on topics related to contemporary art history, aesthetics and cultural studies.