Jiří Skála

Whenever somebody asks me to send in a few photographs of my work I encounter a problem. Sitting in front of the computer, staring at the monitor, I find myself unable to come to a conclusion. Of what do these images speak? Are they testimony to my need to find a compromise between the chaos in my mind and my ability to control it, to know my way around it? What should I write? How can I connect these eleven photographs?

GALLERY | ARTIST’S STATEMENT | SHOWS | COLLECTIONS, PRIZES & PUBLICATIONS | CRITICAL STATEMENT

GALLERY

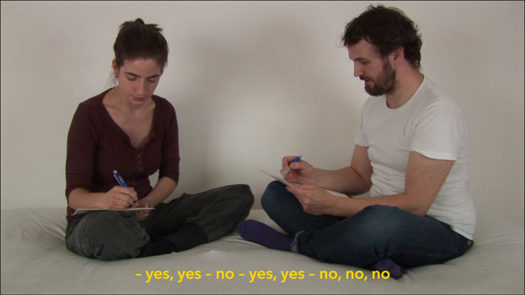

Exchange of Handwriting, 2006, a play involving two people

The first version of this performance took place over 36 working days, from January 14 to March 4, 2006, at Art in General in New York.

In cooperation with Christina Courtin, a Brooklyn based musician, I rewrote 36 short passages from the English translation of the book The Cunning Little Vixen by Rudolf T?snohlídek. 4 hours a day for 18 days we worked on learning to imitate each others handwriting as precisely as possible. After a month and a half, we needed only our memory while copying the text.

The second version took place in the Atrium of Pražák Palace at the Moravian Gallery in Brno from December 13, 2006 to March 11, 2007. For 58 working days, the participants in the project, Andrea Lání?ková and Filip Smetana each learned to imitate each others handwriting. The two participants copied out the essay Taking up Residence in Homelessness by Vilém Flusser.

The third version, took place from August 16th and November 9th 2007 Art at the exhibition Art in General: 25 Years Later in the UBS Gallery in New York, as part of a group exhibition along with 9 other projects that had taken place in Art in General over the years. Each of the participants (Diego Cagüeñas and Kendra Mylnechuk) learned to imitate each others handwriting with a different text – the first was the essay by Vilem Flusser Taking up Residence in Homelessness and the second as the conclusion of Levi-Strauss‘s book Tristes Tropiques.

The forth version, took place from February 25th and May 1st 2011 at the exhibition The Other Tradition in Brussell. Each of a participants (Aurelia de Conde and Alan Fertil) learned to imitate each others handwriting with a text which has been written directlly for this performance.

Two Families of Objects, first part of the project One Family of Objects, 2007, 14 color photographs, Landa print, 50 x 40 cm

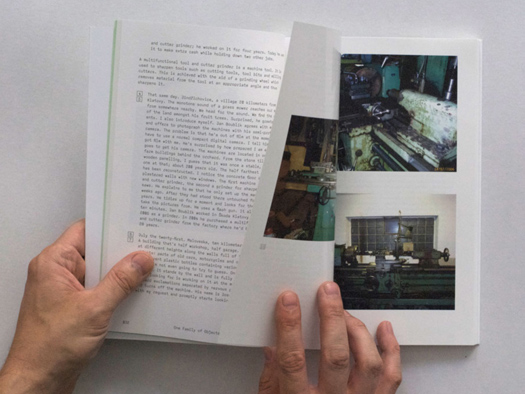

In 2001, my mother, Ji?ina Skálová, received the turning lathe, on which she had worked for close to 22 years, as a present on her 50th birthday. My father Jaroslav Skála bought it for her from the factory where she had worked, which was going bankrupt and was selling off all its equipment to pay its debts to the bank. The factory managed to make it through the early transformation process of the 1990s, but at the beginning of the new century it evidently ran out of breath. My father decided to insure their future by purchasing the turning lathe – equipment that would allow them to continue to keep on working and earning. I asked my mother to photograph this unusual present and to give me the photograph. After this I got to know from my parents, that there are other people who have found themselves in similar situations – those who have purchased the production equipment, on which they had worked most of their lives during the communist regime, from now defunct companies and producers. I have sough out them and i ask each new owner to photograph the machinery themselves and give it to me.

Installation View

Notes Regarding a Request For Help, 2008; short story; 3rd version, 2009, durst print, 118,5 × 175 cm;

Possible Instruction For Seeing Oneself, 2009

short story

2nd version; durst print, 118,5 × 175 cm

Progress Report, 2009; letter; durst print, 118,5 × 175 cm

Sometimes it Really Happens But if it Happens Again… , 2009; essay; durst print, 118,5 × 175 cm

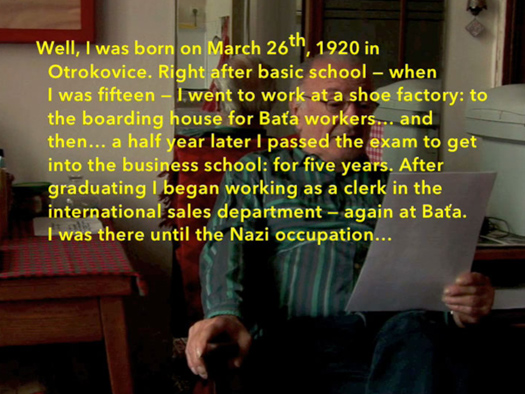

?elechovský/ Mrázek, 2009

Confrontation reading;

HD video, 13 min.; you can see the video at this webside: http://www.vimeo.com/8174375

Father’s Mouth, 2008 a one act play for two people

2nd version, 2009, documentary video of a performance, HD video, 14:01 min., you can see at this link: http://www.vimeo.com/8171242

The Involuntary Archivist, 2009

in collaboration with Zbyn?k Baladrán; A machine for watching a performed short story; digital video, 4 min.; wood and metal construction, 0.9 x 2.45 x 1.8 meters; projector, hard disk driver, HD media player, sound speakers, 2 headphones; you can see the video at this webside: http://www.vimeo.com/9252987

One Family of Objects, 2010

book, A5 format, 1000 copies, publish by JRP Ringier and tranzit.org

Every system change requires for its actors to adapt to it. Their new cultural status is defined according to the success of their assimilation which creates interesting social phenomena. In the case of the author of the book One Family of Objects, Ji?í Skála, it is the social and economic transformation taking place in the Czech Republic in the past 20 years. The concrete subject in question here is the metamorphosing relationship of a laborer and his machine. In the year 2005, in the southwestern part of the Czech Republic, a factory where the author had worked at the beginning of the 1990s and where his parents were employed for several decades, went bankrupt. Most of the machines were sold to new owners – small tradesmen or large manufacturing complexes in India and Mexico. The parents of Ji?í Skála also bought one of the machines. This unexpected decision gave the author an idea – to search for other machines and have their new owners photograph them. Allow the owners to capture, through a camera lens, their relationship to their own manufacturing tool, and find out this way why they bought one of those steel giants that possess such specific aesthetics of green paint, ubiquitous grease and pungent smell of steel dust.

Real Presence, 2010

a narrative imaging machine; digital video, 14 min.; laminated chipboard and metal, 2 x 0.7 x 1.2 meters; data projector, sound speakers, DVD player, 2 headphones; you can see at this webside: http://www.vimeo.com/17188621

A Monument of Coercion, 2010

Imaging machine

2 digital videos, 00:15 min.; plywood, aluminum and metal construction, 1.3 x 4.2 x 90 cm; 2 data projectors, 2 HD media players, amplifier you can see at this webside: http://www.vimeo.com/17187664 and http://www.vimeo.com/17186977

Guide, 2011

a play involving three people plus one operator. set of texts and actions of czech experimental poets (Zden?k Barborka, Bohumila Grögerová, Josef Hiršal, Ji?í Kolá?, V?ra Linhartová, Ladislav Nebeský) and contemporary artists (Zby?ek Baladrán, Aleše ?ermák, Tomáš Pospiszyl, Ji?í Skála, Jan Šerých) in colaboration with Aleš ?ermák and Filip Jakš

Foreign Bodies, 2011

documentary video, 8:27 min., you can see it at this link: http://www.vimeo.com/8171242 confrontational reading in public space

Four performances, the four monuments in Brno, plus one reader and the text; story of an ordinary being, unencumbered by the heroic pathos, the story of a civil servant who has never… This work was inspired by Jan Mancuska, by our discussion five years ago, and by two book – Jacques le fataliste et son maître by Denis Diderot and Les Corps étrangers by Jean Cayrol.

Whenever somebody asks me to send in a few photographs of my work I encounter a problem. Sitting in front of the computer, staring at the monitor, I find myself unable to come to a conclusion. Of what do these images speak? Are they testimony to my need to find a compromise between the chaos in my mind and my ability to control it, to know my way around it? What should I write? How can I connect these eleven photographs?

I was born within a particular context. I know it fairly well, even though it sometimes serves up an unpleasant surprise. But there are some things that I consider immutable and unquestionable. For example, the awareness that I live in a society of the written word. It’s like… it’s like a brightly colored bouncy ball bouncing up and down at breakneck speed. I can see it, but I can’t catch it.

Yesterday, for instance, I was listening to a radio adaptation of Novel of Love and Honour by Jind?ich Honzl, a theater and film director who was capable of sacrificing his aesthetic ideals for the ideal of political theater; to the point where he committed suicide in the year of Stalin’s death. In the radio production, the narrator takes listeners on a journey through letters written by two Czech writers, Jan Neruda and Karolína Sv?tlá. I heard something in their love letters… something familiar. I like to thematize the relationship between a man and a woman, that tension… the way we attempt to approach one another, how one tries to establish contact with the other. But I also heard something else… But how can I put that in words?

The only thing that comes to mind is my favorite quote from Tristes Tropiques by Levi-Strauss. “During the Neolithic age, Man put himself beyond the reach of cold and hunger; he acquired leisure to think […] to say that writing is a double-edged weapon is not a mark of ‘primitivism’ […] Writing might be regarded as a form of artificial memory…” These sentences contain all that I aspire to achieve, which is to work methods of narration that are as diverse as possible. I endeavor to find the most appropriate means of narrating a story within the context of the gallery – a public space where visitors represent only their own selves, their own memories, their own experiences, and where they cannot share a collective experience with others by experiencing the same thing in a different space and a different time. So I endeavor to create situations in which the visitor not only has to confront text, in other words, content, but also its physical embodiment, its form. This is the case in Exchange of Handwriting, where two people attempt to create a new means of communication through each other’s physical marks and handwriting. Or, in the form of textual stories printed on sheets of paper that have the dimensions of the human body and are suspended in space. Or, through confrontational readings such as My Father’s Mouth, ?elechovský/Mrázek, Foreign Bodies, etc. etc. It would take a long time to try to list all these attempts; and the self-statement would become an autobiography.

2010 Messages in an Emergency, Czech Center, New York, USA; You are the Object, I am the Impulse, Václava Špály Gallery, Prague, CZ.

2007 Two Families of Objects, Hunt Kastner Artworks, Prague, CZ

2006 Exchange of Handwriting, Prazak Palace (Atrium), The Moravian Gallery, Brno, CZ; Exchange of Handwriting, Art in General, New York, USA

2005 The Pacific Has no Memory, Eskort, Brno, CZ

2004 Local Stigma, Futura, Prague, CZ; DOS (Labour Union House), poster and billboard project, CZ

2002 Hygiena, Display, Prague, CZ

2001 The Japan Crossing, a public project (with Mark Ther), CZ; Galerie Jelení, Foundation and Center for Contemporary Arts, Prague (with Mark Ther), CZ

GROUP SHOWS

2011 The Other Tradition, Wiels, Brussels, BEL; Brno Art Open 2011, The Brno House of Art, Brno, CZ.

2010 Image at Work, Index, The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden; There Has Been No Future, There Will Be No Past, ISCP, International Studio & Curatorial Program, New York, USA; A Map, Bigger Than Its Territory, Galleri Experimentell,Valand School of Fine Arts, Gothenburg, Sweden.

2009 Fragments of Transformation, Brno House of Art, Brno; Afret velvet, Prague City Gallery; Finalists of the 2009 Jindrich Chalupecký Award, Gallery Dox, Prague.

2008 Monument to Transformation, Fragment # 6: Laber Day, Gallery Labor, Budapest; Ars Telefonica / PhoneBox, Centre for Visual Introspective, Bucharest.

2007 25 Years Later: Welcome to Art in General, UBS Art Gallery, New York, N.Y. , USA; Festival der Regionen 2007 (Exits and Dead Ends), Kirchdorf an der Krems, Austria; Invisible Things, Trafo Gallery, Budapest.

2006 Backstage, Kunstverein – Frankfurt; I invited flow friends to see… , Galerie Nova, Zagreb; I, an exhibition in 3 acts, Futura, Prague; How to Do Things? – In the Middle of (No)where… , International Center for Contemporary Art, Bucharest and Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, Berlin.

2005 1811197604122005, Plan B, Cluj, Rumania; Narrow Focus, Tranzit Workshops, Bratislava; Fifth Biennial of Young Artists, Prague City Gallery at the House of the Stone Bell, Prague.

2004 The 3rd Seoul International Media Art Biennale, Seoul.

2003 Imagética, (in collaboration with Angela Detanico a Rafael Lain), Curitiba; Art Klazma, Moskva; GNS, (in collaboration with Angela Detanico a Rafael Lain), Palais de Tokyo, Pa?íž; Incomprehension, Palais de Tokyo, Pa?íž.

2002 00, Exhibition Which Grows of the Middle, Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

Wannieck Gallery, Brno, CZ

Marek Collectors, Brno, CZ

Frac Lorraine , Metz, F

PRIZES

2010 Jindrich Chalupecký Award, CZ

PUBLICATIONS

Hygiena, paspress, 2002 (samizdat).

I‘m History, tranzit.org, 2005 (editor).

Interpretation, Idea, 2006 (brochure inside the magazine).

Cap Crew Agains People, Bigg Boss, 2007 (editor).

Untitled (1975-2064), Pazmaker and Gallery U bílého jednorožce, 2008.

One Family of Objects, JRP Ringier a tranzit.org, 2010.

CRITICAL STATEMENT – Ján Man?uška

Just how important is Ji?í Skála’s personal information – for instance, in the context of his earlier work? These apparently purely formal works hide personal messages. This is most evident in the installation Volumes of All Members of My Family from 2002 that are transformed into simple block shapes. But in other works, such as Mixer, 2001 (rusty water on the bottom of the mixer) or The Ruler Project, 2000 (an intentional error made a ruler 2 mm longer), a code alluding to a blue-collar origin or metrical rigor of a metal turner lie concealed. This is a content that necessarily accompanies any art work – even a conceptual one and which, eventually, no one wants to see. Or is this an utterly essential part of the artist’s work?

All of these paradoxes combined helped to constitute the current work of Ji?í Skála. Its dominant element is transcription. In the work Handwriting Exchange, 2006, ways of understanding it may fluctuate from thoroughly derived conceptual work all the way to an obstinately physiological and personal need to break through the defining features of one’s own body while making a written record. In the exhibition space he positioned a volunteer with his back to him and taught him his own handwriting. And he learned the handwriting of his counterpart. In this work, as in the Utopian project of teaching an illiterate to write, institutional criticism is delicately unveiled in a more objective form. What are the possibilities of an exhibition space? In some cases the exhibition space makes certain things impossible. For instance, political engagement is stripped of its consequences and responsibilities – it’s put into inverted commas. On the other hand, some things are only possible in an exhibition space (even on a political or social level). Teaching an illiterate to read and write could be understood as social work, though in the human context it could be perceived as aggressive and arrogant. Yet, the exhibition space brings the meaning into sharper focus: this has nothing to do with social work, the art work does not replace the function of education, instead, it examines, from art’s point of view, the structure of a human skill and its influence on our consciousness. More, on the human level such a project can be carried out only thanks to the exhibition space. For all is possible in a space that puts everything in inverted commas.

The project Two Families of Objects, 2008, also initially concerned transcription. The original goal was to photograph the means of productions, machine tools owned by ordinary people from the factory where Skála’s parents worked. This was a transcription of the beauty of machines (against the backdrop of the economic relations of early Czech capitalism) into pictorial and photographic forms. During the ensuing work on a book that was supposed to expand this project, Skála came across the reality of the sold-off assets of the factory from which his parent and others were fired after its bankruptcy. Thus, he came across the problem of morals, a very problematic theme in art. Following the modernist understanding of morals as something that needs to be destroyed, morals have reappeared paradoxically as inheritance from the 1960s. More, in many politically engaged actions, after removing the chasm between the autonomy of artistic expression and political activism, their moralising aspect becomes the only thing that remains. This problem also concerns the DOS (House of Unions) project, 2004, when Skála placed a billboard with a photograph of the headquarters of labor unions in Prague across from the entrance to the Hypernova supermarket. If we leave aside the ambivalence of the beauty of a functionalist building that exemplifies the fact that the theme is reviewed from the position of art, we cannot claim that such a project would change in any way the working conditions in Czech supermarkets. The building itself lacks emphatic symbolism. What’s more, the political reality that Skála touched upon is much more gruesome than one which a project of this type could change. It acts as an unanswered question to be taken up by those who are among the potential viewers of contemporary art. And their number is not in any way restricted. Actually, it’s everyone and that’s where the strength of the project lies.

The paradox of thorough conceptual work and reference to its own background and personal disposition that undermines the former always surprises the viewer of the works by Ji?í Skála. The element of surprise does not happen all at once. Instead, it sneaks in when the viewer is thinking of his work. It’s like retracing the steps by which Skála reached this point, identify his thought process with one’s own thinking and then put everything in the context of his past projects, which compose an ever clearer picture of Skála’s interest. Together they verify the themes that he touches upon. Eventually, one only needs to put everything back to the place where Skála came from and where he has lived his whole life.