The OHO Files: Interview with Milenko Matanović

ARTMargins Online publishes exclusive interviews with former members of the Ljubljana-based OHO Group, which formed in the late 1960’s and consisted of Milenko Matanovi?, David Nez, Marko Poga?nik, and Andraž Šalamun. It belonged to the wider Slovene OHO Movement and regularly collaborated with this wider circle of intellectuals and artists.

Milenko Matanovic is an artist and community organizer, founding the Pomegranate Center, whose mission has been to develop an effective model for helping communities prepare for the future using collective creativity, meaningful engagement and powerful collaboration. Matanovic began his career as an experimental artist in the late ’60s in his native Slovenia, exhibiting all over the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as part of the artist collective OHO. At the age of 24, feeling like his art career was no longer helping to push art-making into everyday life – it was living in museums and private collections – Matanovic left the artist collective and began learning how art could serve community better.

Beti Žerovc: How did you come together as a group?

Milenko Matanovi?: It was a gradual process. Aleš Kermavner and I attended the same high school and became friends and Aleš introduced me to Marko Poga?nik and his grilfriend Marika. We visited them several times in Kranj and I met their friends, including Iztok Geister and Nasko Križnar, who then involved me in several of his films. Marko was already fully focused on art and I was just beginning to work on it seriously. I initially helped Marko with his strip installations, and later brought a kitchen table to that same spot under Kazina from my home on Wolfova street and we sold our books and articles (like my visual gramophone records). Marko was a visual editor at Tribuna and organized art exhibits at Kazina where Tribuna’s offices were located. I had my first display of drawings there and, after Marko graduated I took over his position at Tribuna. I became friends with David Nez and Andraž Šalamun during those times. We spent lots of time together doing silly things, but also started making serious sculptures and paintings that we brought to Zvezda Park for display. Eventually, art became the focus of our friendship and we often joined on field trips to try things out, encouraging and influencing each other as we worked.

BŽ: Did you feel connected to the things Marko Poga?nik was doing before, or did this feel like a new, independent structure? And, Was there maybe a connection to your previous work, or to the previous work of David and Andraž?

MM: The connection for me was initially on a friendship level. My memories of Slovenia in the 1960’s are of a socially foggy and grey space. I couldn’t bring myself to follow the expected path laid out for me – I felt that to succeed by the prevailing standards would force me to fail as a human being. Artists who gathered around OHO had sunnier and more positive dispositions and a sense of humor, and this attracted me first and foremost. As the friendships grew it became natural to collaborate on art also. All my knowledge of my OHO friends’ art was acquired during our growing collaboration.

BŽ: I understand that the atmosphere among you was very »relaxed,« but still at some point the four of you became a recognizable group. As far as I know, Tomaž Šalamun was doing a lot of visual projects, but he somehow is not perceived as a member of OHO. Do you remember how the group came to be made up of four members?

MM: Initially we created informal opportunities for sharing our individual work. My recollection is that the group didn’t come together until the first exhibit—I think at the Gallery of Modern Art in Ljubljana—, and we had to get organized. I do not recall who made the selections of artists. Marko was the front man and I think that he negotiated the exhibit. I simply recall that I was invited and that we very quickly received invitations to exhibits in Maribor and Zagreb and the group became more formed with each invitation. The core group was Marko, Andraž and myself, and later David. Tomaž Šalamun drifted in and out of visual art. Poetry was his main expression and he got involved on several occasions, but not on an ongoing basis. I think his art was a visual extension of his poetry while for the rest of us it quickly became the main focus.

Marko lived in Kranj, but for those of us in Ljubljana, Tomaž and Taja Brejc became important friends and allies. We would often hang out at their home. They had international art magazines that I would peruse. I am sure that some of those pictures influenced my artistic imagination. In addition ,Tomaž, an art historian, was a keen observer of our activities and wrote about it. The opportunities for exhibits were undoubtedly assisted by his writings.

BŽ: Can you describe the interaction among the group members?

MM: I remember how easily we collaborated. Someone would have an idea and we would jump in and add our improvisations on that idea. For example, Marko had a friend who had a forest and suggested we do installations there. We all purchased different materials and spent a day doing individual installations. We would invite each other to see the works and were easily influenced by each others’ ideas. I think that we were all helped by this jazz-like improvisation—playing similar tunes, but in different ways. I am still grateful for that experience and use it now in my work with Pomegranate Center.

BŽ: How did you work? If you knew that you would have a show a few months or a year later, how did you prepare for it? Did you make new works for the show, or did they exist before and were then just exhibited?

MM: I found myself working in thematic waves and that meant that I usually knew in essence what I would do at a show, but the actual specifics were always figured out on the spot, after seeing what the space offered. For example, I knew that I wanted to do something at the Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade that linked the indoor space with the natural area surrounding it. It was only after studying the site that I decided on installing a series of mirrors in the landscape in such a way that they reflected sunlight onto the Museum entrance every hour. The installation only worked for a few days because the mirrors were stolen. Another example: for some time I had been thinking about exhibition spaces as a volume and I wanted to do something that showcased the entire space.

When I took my first airplane flight to Belgrade I was awestruck by the beauty of clouds and that gave me the idea for the smoke bomb that I released in the Student Gallery in Belgrade. Unbeknownst to me, the gallery space had a ventilation system that carried the smoke into a fancy restaurant where lots of important politicos ate, and the smoke forced the closure of the restaurant. Of course I was accused of political sabotage when in fact I didn’t even know about the restaurant’s existence. The reaction to Triglav was initially political as well;-apparently there was a pre-war organization with that name and I was accused of being a sympathizer. Also my friends and my brothers would send me articles offering explanations of the work. I tried to tell anyone who would listen that the idea for Triglav—which means “three heads”—was simple: it was late December just before the new year, and traditionally people give gifts to each other at that time of the year, so I thought of offering the people of Ljubljana, especially those too feeble or old to venture into the mountains, a gift by bringing the mountain to the city. At home we had a sculpture of three heads (my two brothers and me), and I always thought of it as a “triglav.” So it was perfectly logical to invite David and Drago Dellabernardina, two willing colleagues, to sit on a tall ladder with me, covered with a plastic tarp for a few hours, pretending to be a mountain. We froze our butts sitting there in the cold, but it was fun well worth it.

BŽ: I assume that you were aware of what I would call the great power and symbolic potential in the events on which you were working. . Was that more intuitive, or did you talk about this, may be even have a theory about it? In the past you have spoken about Triglav as a gift…

MM: I am not sure what you mean by “great potential.” If you mean the significance and meaning of what we were doing, then I would say I was completely unaware of it. My art was improvisational. Using very inexpensive materials made it possible to create quickly. I think I was engaged in playful explorations, not in theories. In fact I resisted theory and instead simply trusted my intuition and impulse. I wasn’t afraid to try things out; if it felt like a great idea, I found a way to implement it quickly, without thinking it out too much and running the risk of editing it and watering it down. Some projects didn’t work out, but they led to other more successful ones. It didn’t occur to me to create something in order for it to be significant or “meaningful.”

BŽ: Were people invited to attend works such as Installation with a Wooden Stick? Who was invited?

MM: When I worked at a convenient location I would invite people to see the installations. For example, I put the word out when I created the wood and string installations at Rimski Zid, or when I exhibited Sunset one evening at Zvezda Park. I called my colleagues and friends on the phone or printed a small flyer inviting them to the event.

BŽ: I have chosen a number of your works I would like you to comment on. (All these works are reproduced in the OHO catalogue, edited by Igor Zabel and published by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in 1994. In the following listings, the year of production is followed by the number of the page on which it appears in the catalogue.)

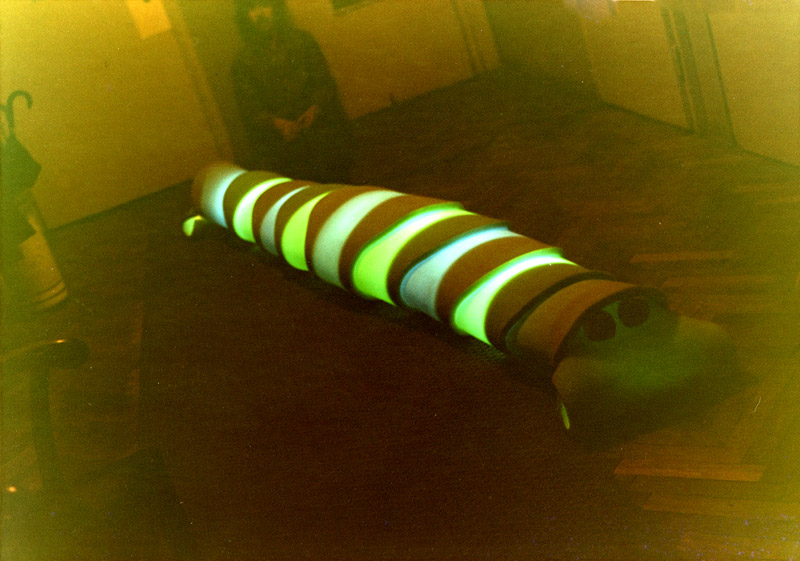

1. Object The Worm, 1968, p. 34.

I would regularly visit hardware stores to see what interesting materials I could find there. I bought sheets of foam and the “worm” was the first object I created with foam. I had it at home only—I do not think that it was ever shown publicly—, and I also put lights inside the work so it would glow. I used UHU glue to tie pieces together.

2. Object Made from Egg Cases, 1968, p. 35.

I had a special fondness for egg cartons. I liked their shape, and felt that it was a shame to throw them away after use. So I did a series of objects painting them in a variety of combinations, highlighting their geometry.

3. Happening in Zvezda Park (A vacuum cleaner filled long plastic tubes with air), 1968, p. 38.

I bought a role of plastic (I think it was used for plastic bags) and I used a vacuum cleaner to fill it with air. I invited friends to come to Zvezda Park and about twenty came and I asked them to form a circle. As the unfolding tube would reach them, they were to gently redirect it back towards the center of the circle. The tube unfolded quite slowly: it took about twenty minutes over which it grew in size until the circle was filled with the twisted tube.

4. OHO – Katalog: Happening the Passion (or Biblical Stories), 1968, p. 39.

At BITEF we were asked to create an exhibit and also an event/happening in the theater hall. For the exhibit I created a sculpture called Red Sea, a series of wavy wooden boards that I painted red. When we discussed what to do in the hall, I suggested parting the Red Sea as a theme and we’ve agreed to improvise around it. We got hold of a large role of cardboard paper and after people settled into their seats we rolled the paper over everybody and then punched holes in it so people could stick their heads above it; we turned people into a “sea” and their heads into “waves.” This took quite a bit of time. And then we used karate chops to break the paper andwe “parted” the sea Moses-like. Then we walked out. It was all very strange and humorous, especially because we didn’t use any words and none of us had any performing experience. It left people completely puzzled. All in all it was a fun project with lots of potential but rather poor execution.

5. Milenko Matanovi? Makes a Path, 1968-9, p. 43.

I did this piece in Barje (I enjoyed visiting there) and noticed the many animal and human paths. I was intrigued by the idea of making my own path (I also liked the poetry of that act) by tramping down a line in the grass that didn’t exist before.

6. The Fifteen Hills of Rome, 1969, p. 48.

This piece was made with old umbrellas that I opened, cutting the handles. This allowed only the upper parts to be placed on the ground. I put hemp on top. Looking back, I think the project would have been better without the hemp; it would certainly have complimented David’s roof better.

7. Installation with Wooden Sticks in the Forest, 1969, pp. 60-61.

When we agreed to work in the forest, I instantly wanted to work with wood. I liked the idea of processed wood “visiting” the place where it “grew up.”

8. The Snake, 1969, p. 62.

I lived at Wolfova 1 and we had access to the balcony overlooking the Ljubljanica River. I always liked looking for fish from the balcony, and while doing so I noticed the almost invisible currents that moved through the channeled water. I started to think about how to make those currents more visible and came up with a “snake” of wooden pieces connected by a rope. I was delighted to see the snake form replicate the slow, beautiful, meditative and meandering movements of the river.

I did a sister piece that similarly highlighted the rolling landscape around Medvode. I bought a role of paper, some 200m long, and simply rolled it out. Influenced by gravity, the paper meandered through the meadow in a most beautiful way. But I haven’t seen any pictures of that piece.

9. Wheat and Rope, 1969, p. 63.

The summer of 1969 was a wonderful time for me. I found very inexpensive materials–string, wood, paper–to highlight what I noticed in nature. I placed a stick in the ground on one end of a wheat field, attached a rope to it, and then tried to attach it to another stick at the other end. The resulting tension uprooted the stick, so I settled for bending it by hand. I wanted to create many more projects with this method with many lines on a field, but I never got around to it. Perhaps I will one of these days.

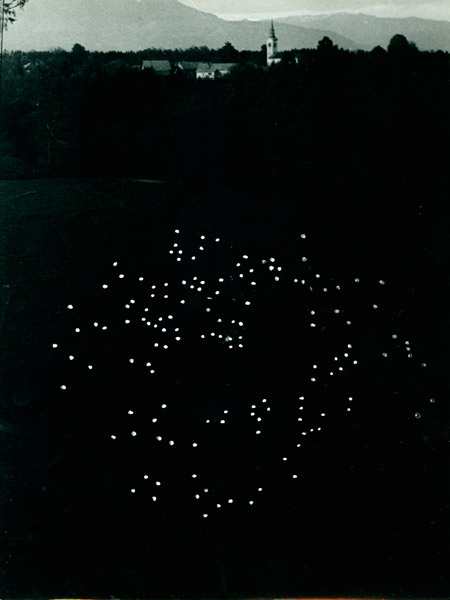

10. Project, 30. April 1970. The constellation of candles in the field corresponds to the constellation of the stars in the sky, p. 95.

I wanted to do something that would capture the mystery or Zarica. I did a series of experiments with candles there. I brought a drawing of major star constellations to Zarica and then aligned the candles with the stars above. It was beautiful while it lasted. My candles burned out in about one hour.

BŽ: Did any of OHO Group’s works have a special status (good or bad) already back then?

MM: As I said before, I did not see the work as important (or unimportant). However, I liked our work in the Zarica valley when we started to link space and time in a series of wonderful explorations. I felt that there was more to be done with the ideas we started to explore there. I liked my Earth from the Moon installation using a role of tarp paper and a simple light – I thought it was a humurous and cheap version of the Apollo flights that were taking place at that time. I especially liked how I was able to make visible the invisible currents in the Ljubljanica river. I also liked Andraž’s piece tracing stick shadows throughout the day and

I liked Marko’s drawings, especially his medial point series.

BŽ: How did people react to your work; do you have any special memories in this regard?

MM: Most of the work was done with very few people around. Nobody told me to stop doing what I was doing. A small group of colleagues and friends followed our work, and we encouraged each other. Mostly it was all just a »happening«, and didn’t need or receive any approval. I did request official approval when I applied for the status of being an artist. I felt that I should be accepted because I represented Yugoslavia in international exhibits. However I was turned down twice.

BŽ: Besides that, did you have any serious trouble because of your work?

MM: Once, I think it was in 1969, I was taken to a police station where a couple of plain-clothed policemen asked me about my life, but mainly wanted to let me know that I was being watched. They showed me a large binder and asked me if I wanted to know what I had been doing on a specific day. They pulled out a page: »on such and such a day you had coffee at 8:15« ; »you bought socks at 11:17 at Nama«; etc. They wanted me to know that I had been observed, nothing more. I was never bothered again. At first I was upset and found it unsettling. A few days later I took a more generous view: I was proud of myself for providing jobs for several individuals; I was helping the economy.

BŽ: How do you remember OHO Group’s dissolution? Did you all agree on that to happen? How and why did that happen?

MM: There were several things that started to happen at the same time. The most important one for me was that rapidly I became aware of new interests beyond the field of art. I became interested in meditation and spirituality, for example. I had a keen sense that our collective human pursuits were perilous to nature. I was fascinated by the Apollo 8 image of Earth from space at the end of 1968 and sensed the importance of that moment – that we humans were able to see ourselves from a distance. I wondered what changes in our collective self-awareness would result from this. Though I used recycled materials in my art, increasingly I had a sense that I needed to go deeper and try to better understand ecology.

But mainly we felt that the path open to us through art exhibits in museums and art galleries was too narrow and that it led to an increasingly specialized activity that would, over time, narrow rather than expand our pursuits. We had conversations about all this amongst ourselves, and over time it simply became common sense to try new things. I do not think of that time as ending, but beginning a whole new track that eventually led me to create Pomegranate Center in 1986, a non-profit that started with the premise that art belongs in life and in the community, and that creativity should be used to address the problems facing humanity. I still do art, but not in museums and galleries. I rather go to main streets, parks and other gathering places, or schools. To me this is a logical extension of the work I began with OHO.

BŽ: Why did you go to the USA?

After OHO, I willingly and consciously embarked on years of new exploration and learning. I knew I needed to better understand what was happening in the world, and I therefore started to travel. My friend Marjana had heard about the Findhorn community in Scotland and we wanted to visit. We hitchhiked there in the autumn of 1971. She was going to stay there while I was going to return to Slovenia. It worked out the other way around. Marjana returned and I stayed because I made friends with several Americans who remain my friends to the present day (one became my wife), and because I thought I could learn something there. Findhorn’s foundations are spiritual. Its founders believed that people are capable of a deeper understanding of cultural and natural processes and that the quality of our existence improves when we act in synchronicity with those forces. The most impressive aspect of the community is its organic gardens and the eco-village utilizing green methods, a clear and practical demonstration of the community’s values. Both David and Marko found their way to Findhorn, but by then I had already left.

I moved to the USA in 1973 and made my living in part by writing and performing music, and by collaborating with cutting-edge individuals and visionaries who were creatively addressing cultural problems. For example, I collaborated with Dr. Belden Paulson and his wife Lisa who started an ecological community in Wisconsin. I brought John and Nancy Todd to Yugoslavia, pioneers in ecological design who invented the so-called bio-shelters, passive solar homes that include greenhouses for food production, as well as “living machines,” i.e., sewage plants that recruit microbes and plants to make toxic water reusable. I also worked with James Parks Morton in New York, the “green” Dean of the Episcopal cathedral who led the ecological revitalization of the neighborhood. I consulted with non-profit organizations in Chattanooga, Tennessee, helping them explore how to create an environmentally vibrant city. I learned a lot from these individuals and the work, and I immersed myself in American society. I married a great lady and we have two wonderful daughters. One of them works with me at Pomegranate Center, the other is just starting her opera career. I tried to understand how democracy works, how cities are designed, how people from different cultures can coexist, and how I could utilize my artistic skills to address the problems I saw around me. One thing led to another and in time I realized that my unique experience should be put to good use. I created the non-profit Pomegranate Center in 1986 to for this purpose (www.pomegranate.org). Now I work throughout the USA and Canada, helping communities plan for the future, building gathering places, and training leaders in Pomegranate Center’s hard-learned skills.

BŽ: Many thanks for this conversation.

[su_menu name=”OHO”]