Wolfgang Beilenhoff and Sabine Hänsgen (eds.), “Der Gewöhnliche Faschismus” (Film Book Review)

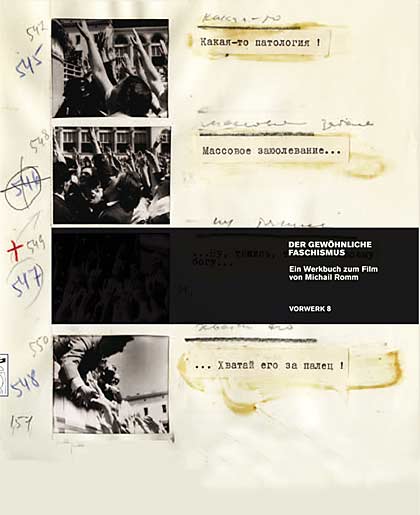

Der Gewöhnliche Faschismus. Ein Werkbuch zum Film von Michail Romm. Wolfgang Beilenhoff and Sabine Hänsgen (eds.), in collaboration with Maya Turovskaya. Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2009. 335 pp.

Ironically, last year’s celebrations and world-wide media attention surrounding the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall coincided with the publication of a book which quite unexpectedly throws light on an aspect of the history of the two German states that remains unresolved to this day: the heritage of National Socialism on both sides of the Wall, and in reunited Germany. The publication is on Mikhail Romm’s film Ordinary Fascism (USSR 1965), edited by Wolfgang Beilenhoff and Sabine Hänsgen in collaboration with the scriptwriter of the film, Maya Turovskaya. It centers around the first German edition of a photo-text book about the film designed by Romm himself, reconstructing all of its 16 chapters in a dense montage of stills, printed voiceover text, and author’s comments. The original Russian version of the book, which was to appear in Izdatelstvo Iskussvo’s Masterspieces of Soviet Cinema series in the 1960s, never passed the Soviet censor and was not published until long after Romm’s death in 2006.

Ironically, last year’s celebrations and world-wide media attention surrounding the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall coincided with the publication of a book which quite unexpectedly throws light on an aspect of the history of the two German states that remains unresolved to this day: the heritage of National Socialism on both sides of the Wall, and in reunited Germany. The publication is on Mikhail Romm’s film Ordinary Fascism (USSR 1965), edited by Wolfgang Beilenhoff and Sabine Hänsgen in collaboration with the scriptwriter of the film, Maya Turovskaya. It centers around the first German edition of a photo-text book about the film designed by Romm himself, reconstructing all of its 16 chapters in a dense montage of stills, printed voiceover text, and author’s comments. The original Russian version of the book, which was to appear in Izdatelstvo Iskussvo’s Masterspieces of Soviet Cinema series in the 1960s, never passed the Soviet censor and was not published until long after Romm’s death in 2006.

In contrast to its original layout, the material is here reproduced on a black rather than white background, like film images appearing on the screen out of the darkness of a cinema space. As Beilenhoff and Hänsgen point out in their introduction, they have chosen this formal inversion to highlight the various translation processes inscribed in the film (which transposes German images into a Soviet film scenario, mediates between photography, film and text, between different artistic traditions), as well as in the publication as it traces the history of the film’s production and reception between different publics and political systems.

Along with an excellent introductory text by the editors discussing the film in its political and media historical context, the book assembles a unique selection of rare or previously unpublished materials about the film. This includes essays by Romm and his editors (Yuri Khanyutin and Maya Turovskaya) on the production process, Turovskaya’s account of the film’s reception in the Soviet Union and Eastern Germany, theoretical reflections on film, memory and the archive, interviews, recollections, and reviews. Positioned between film and political history, art and theory, the publication manages to recreatethe very polyphony characterizing the film as well as the feedback it generated in both the East and West.

Romm’s film combines material selected from two million meters of German newsreels (wochenschau), educational and amateur films, photographs collected in archives in the Soviet Union, Poland and Berlin, together with footage shot specially for the film. It thus adapts Eisenstein’s “montage of attractions” to develop a new documentary language. Romm describes in his essay how his editing was focused entirely on the silent image in order to achieve an immediate impact of purely visual associations on the spectators. In his use of radical contrasts and discontinuities in the filmic sequence–directly juxtaposing life and death, suffering and hope, violence and joy–he was not merely aiming at a formal effect of defamiliarization, but rather at generating a moral subtext without moralizing.

Through Romm’s intervention the various images, originally designed to mirror and celebrate National Socialism’s achievements and executors, finally started to testify against themselves. They create a visual narrative against the backdrop of which the author’s comment is heard not as a neutral, extra-historical voice, but rather as an individual subjective voice. Romm makes it clear that he meant the film to be a hybrid that does not claim to uncover the truth about Nazi Germany, but to put forward a fragmentary narrative suggesting possible readings of history and its relevance for us today. At the same time, one cannot fully estimate the scope of his formal innovations without considering them in the historical context of the “thaw period.” For Romm, whose early feature films–especially Lenin in October (1937) or Lenin in 1918 (1939)–had played an integral part in shaping the visual language of Stalinism in the 1930s, the making of Ordinary Fascism was part of a critical self-reflection in which his former role as “state artist” in a totalitarian regime is at stake.

Questions of voice and perspective are central to the book’s argument, as these elements are crucial to the film’s formal structure–e.g. the use it makes of the author’s voice, and the light it throws on what we see, as discussed in depth in Beilenhoff’s and Hänsgen’s introduction–as well as to the film’s multifaceted reception and critical afterlife. Can or should “totalitarian” images be allowed to speak for themselves, or do they require a framework that neutralizes their suggestive force? Can the makers trust the audience not to trust them? And doesn’t a film that exposes the inhumanity of German totalitarianism automatically undermine the status quo of its Soviet counterpart as well? In the tense atmosphere of the Cold War period, it seemed imperative to leave no room for ambiguities, and so the openness of Romm’s film made it potentially suspicious.

Turovskaya’s reconstruction of the film’s release and its repercussions in political and diplomatic circles in the Soviet Union and both parts of Germany testifies to the general confusion as to how its critical potential should be judged. The fact that the film premiered at the Leipzig documentary film festival before it was even published in the Soviet Union seems to indicate that the Soviet officials perceived its screening abroad as a welcome test run, thus avoiding a possible scandal at home. The film’s further fate seems typical of the period: after its successful cinema release in the Soviet Union, which for a while even made it a compulsory element of the school curriculum, it was never shown on TV and later practically disappeared from distribution, though it was still being available for closed screenings.

In the German context, reactions to the film are marked by a similar degree ofambivalence. When it was first shown in the two German states, it appeared with two different introductory sequences, embedding its narrative in the respective ideological master discourse. Erika and Ulrich Gregor, founders of the Friends of the German Cinematheque in Berlin, where the film had its West German premiere, even tell of an act of self-censorship on the part of the author, who is said to have eliminated a sequence in which West Germany is accused of revisionism just before the screening. Equally, the numerous reviews and public reactions that the book assembles reflect the political sensibilities of the period, making it appear not only as a critical analysis of National Socialist ideology, but as an ideological (anti-fascist or pro-soviet, depending on one’s political standpoint) statement in its own right.

Despite the fact that Romm’s film is so obviously a product of its time, it has by no means lost its significance today. It is one great achievement of this book to present us with the extraordinary polyphony of Romm’s film and its repercussions in art and society; another is to remind us of the still unfinished history of ordinary fascism.