Dmitry Gutov’s Used at Guelman Galery, Moscow

Guelman Gallery, Moscow, April 3 – 23, 2008.

Dmitry Gutov, a leading Russian artist and a long time member of the Moscow intelligentsia, did not have to go far when he went in search of objects to weld together sculptures exhibited at the Guelman Gallery this past April. All he needed was found dumped in his parents’ garage. While the old bicycles, vacuum cleaners, and radios might look like junk to us, to Gutov they are precious relics of a quickly receding time in Russia’s turbulent history. “These objects are dear to me”, says the artist. Welded onto grids of long metal rods that evoke window guards, these captured objects find their proper frame of reference. We face walls of broken, but somehow still relevant objects, refuse of the artist’s youth in the 1960s, a period of Krushchev’s Thaw filled with hopes for a better future. The Soviet Union, savagely battered by the Second World War, was to become a power on a par with the democratic West.

Gutov who proudly restores value to humble objects of the Soviet time, grounds his motivation in his faith in Socialism as well as in the cheerful abundance of consumer goods that the 60s produced. He propagates a Marxist-Leninist aesthetics and is a founder of the Lifshitz Institute which is devoted to the legacy of the controversial Soviet-era art philosopher Mikhail Lifshitz.

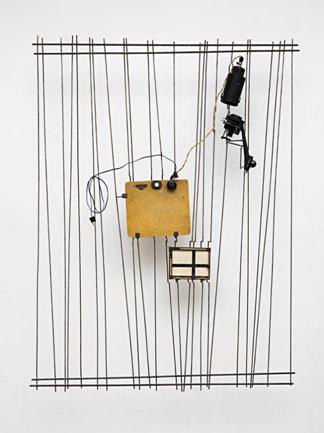

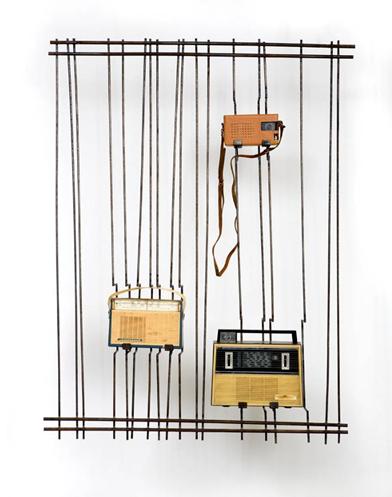

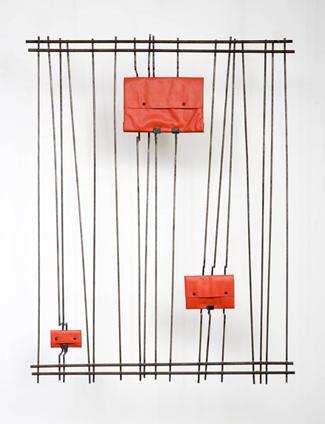

Throughout histwenty five years of practice in painting, installation and video, Gutov strove to revive the Soviet past and bring it into the present. It seems that in Used he is taking this path for the last time. Gutov does not want to keep these historical artifacts any longer, and if someone should buy his sculptures, they will find a better home. At Guelman Gallery, Gutov carefully arranged the broken items in the 13 wall assemblages thereby resurrecting them from junk and imbuing them with the symbolism they once held. Thus a radio was once an emblem of the truth that people waited to hear from the broadcast of Voice of America that could barely be heard because the signal was being jammed. An old camera and photo projector references the time of analog photography, the artist’s creative beginning, and the ready-made of modernity.

Shaped according to streamlined patterns, these objects speak to us in a way that may be best described as the “future in the past”. For instance, the vacuum cleaner resembles Sputnik, a space object that brought pride and excitement to every household during the Soviet Union’s pioneering advances in the space race. New technology was sexy too, as the cord of a small fan swirls as gracefully and seductively as a cat’s tail. Since then, these shapes have been supplanted by newer designs, “the energy of that time has gone” says Gutov with a whiff of nostalgia for the zeitgeist of the 60s. These are the objects the artist has caught in his rectangular nets, a parallel in some ways to the thrill that Nabokov felt as he hunted a new species of butterfly for his collection. In the Used exhibition we can also feel the references to other masters of nostalgic clutter: the careful arrangements of old things by Joseph Cornell, and the mounds of Soviet trash of Ilya Kabakov. Like Kabakov, Gutov hoards objects as a sign of his longing to capture time before it disappears.

Deceptively weightless and floating, the artifacts are fixed to the surface of each assemblage. The artist and his technician have deliberately bent rods around each of the items. Gutov admits to the technical challenges in welding together every joint over an area of 78×46″, the size of the screens. The artist has gained some experience in working with metal over the past two years and he exhibited welded screens with handwritten texts by Karl Marx at Documenta last year. These fine constructions commemorated the trend of neo-Marxism that arose in the 1960s. The artist admits that the idea of using a metal grid came from the type of fence that Russians favor for guarding their long-denied private property. ????? ? ???????? sokiai vaikams .

But Gutov’s rods have yet another connotation: they refer to the institution of prison – another tragic part of Russian history. By bending the bars that confine these everyday objects, the artist refers to the process of de-Stalinization that took place in the 1960s, injecting a breath of freedom into politics and the arts. It was an era of liberation even at the household level, introducing the time-saving appliances commemorated by Gutov in this exhibition.

But why did the artist suddenly decide to part with the once-cherished objects? This exhibition is not only a farewell to the symbols of the artist’s youth but also to the hopes that sustained him up to now. At a time when Russia is slipping into a reactionary neo-liberal phase, the aspirations of the 1960s have vanished forever. Gutov longs for the wave of democratic change that emerged in the first post-Soviet decade and that has since been abandoned since in favor of newly oppressive policies.

Additionally, Used functions as a farewell to modernism and 20th-century art more generally: the ready-made has been replaced by consumer oriented production. “The whole world has entered a void” says the artist. Regardless of such despairing thoughts, the sculptures exhibited here are not give-aways, but have been sold for a fair market price. In the hands of the artist, these second-hand memorabilia have regained their cachet and may now satisfy a collector’s ambition.

This review is an expanded version of a review originally commissioned by Flash Art.