Practicing Solidarity in Slovakia: The Story of Kunsthalle Bratislava

Since the beginning of its mandate, the newly elected (2023) Slovak government has been spreading discriminatory, homophobic, and xenophobic narratives, and proposing new policies, usually without any public debate or negotiations with the professional public. The new Minister of Culture is Martina Šimkovičová from the Slovak National Party (SNS), who formerly worked at the private television station Markíza (from which she was fired after her hateful comments against refugees on social media in 2015).(Tomáš Kyseľ, “Z Markízy ju vyhodili, Pellegrini s ňou mal problém a médiám sa už teraz vyhráža. Kto je Martina Šimkovičová,” Aktuality.sk, October 17, 2023, https://www.aktuality.sk/clanok/yc6re50/z-markizy-ju-vyhodili-pellegrini-s-nou-mal-problem-a-mediam-sa-uz-teraz-vyhraza-kto-je-martina-simkovicova/) Šimkovičová has become a prominent face of the Slovak disinformation scene, for example in her role as a moderator of the internet television TV Slovan. Šimkovičová’s new “vision” for Slovak culture is “to build the cultural sphere on Slovak cultural heritage, the national builders and historical milestones of the Slovak nation.”(Martina Šimkovičová, “Kultúra slovenského ľudu má byť slovenská a žiadna iná,” DenníkN, November 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIi_SHs8dAc) The new vision, however, does not only influence the sphere of what the minister perceives as the “true” national Slovak culture, but has also begun to directly impact the content of cultural production. The minister announced her desire to introduce new legislative changes that would enable her as a minister to gain more power over the content of “Slovak” culture.(Barbara Komárová, “Quo Vadis slovenská kultúra?,” Artalk, December 7, 2023, https://artalk.info/news/quo-vadis-slovenska-kultura; Jana Močková, “Umelec Andrej Dúbravský: Tu nejde o mňa, ale o to, že ministerka by chcela mať dosah na to, čo sa vystaví a čo nie,” DenníkN, December 3, 2023, https://dennikn.sk/3710557/umelec-andrej-dubravsky-tu-nejde-o-mna-ale-o-to-ze-ministerka-by-chcela-mat-dosah-na-to-co-sa-vystavi-a-co-nie/; Bohunka Koklesová, “Šimkovičovej vyjadrenia o LGBTI+ sú začiatkom jej politického konca,” DenníkN, January 14, 2024, https://dennikn.sk/3773618/simkovicovej-vyjadrenia-o-lgbti-su-zaciatkom-jej-politickeho-konca/?ref=list) Šimkovičová, known for her homophobic rhetoric, also announced that the ministry would no longer contribute anything from its budget to artistic production with LGBTQIA+ content or the activities of non-governmental organizations promoting an “LGBTQIA+ agenda.”(Martina Šimkovičová, “LGBTI+ mimovládky už od ministerstva kultúry nedostanú ani cent,” DenníkN, January 12, 2024, https://dennikn.sk/minuta/3772336/)

This new nationalistic policy has affected not only the social and political climate in the country, but also the contemporary art sphere, as was reflected in the fate of the state-funded contemporary art gallery Kunsthalle Bratislava. Kunsthalle’s director, Jen Kratochvil, resigned on January 16, 2024, as the Slovak Ministry of Culture revoked funding for its 2024 artistic and educational program, which had been prepared by the Kunsthalle’s internal and external curators. Consequently, the ministry announced that Kunsthalle Bratislava would lose its independence and become part of the Slovak National Gallery (SNG). As it turned out, however, on February 28, 2024, Kunsthalle Bratislava was informed that due to the rationalization and optimization of the Kunsthalle’s activities, the employment contracts with the Slovak National Gallery would not be continued, leaving all Kunsthalle employees without work starting April 1, 2024.

Handing in signatures for the resignation of Minister of Culture Martina Šimkovičová on February 5, 2024. Photo: Olja Triaška Stefanovic

My own relationship with the Kunsthalle is very personal, as I worked there between 2022-2023 as curator of editorial programming. As part of my role, I created the online publishing project Critical Thinking Series and edited a printed anthology entitled Wandering Concepts (2023), consisting of English-language essays by thinkers, art theorists, curators and artists, translated into Slovak for the first time. Its precise aim was to highlight the importance of translation and to make the knowledge available to the broad public (the publication is available free of charge, also as an e-book on the Kunsthalle’s website). In the introduction of the anthology, I write: “In the region of Central-Eastern Europe, where Kunsthalle Bratislava operates, there have been many recent instances of neo-authoritarian governments attempting to rewrite history and restrict the rights of minorities. […] The proposed solution in this book is to think through ‘wandering concepts’. To think relationally and mutually with others in the world.”(Denisa Tomková, ed., Wandering Concepts/Putujúce koncepty (Kunsthalle Bratislava, 2023), pp. 14-15.) I believed that the book would “offer a small contribution to challenging the local narratives restricting minority rights while contributing to critical thinking that empowers marginalized individuals and communities in the region,”(Tomková, ed., Wandering Concepts/Putujúce koncepty, p. 15.) but it did not occur to me that I was writing these words so close to the context of the coming right-wing changes and the end of Kunsthalle Bratislava. In what follows, I examine the different aspects of the new Slovak government’s nationalism, comparing its rhetoric and strategies to other recent events in the region, and consider how this nationalist agenda (and its specifically anti-LGBTQIA+ elements) has impacted contemporary artists and art institutions in Slovakia.

Political theorist Isabell Lorey, using Stuart Hall’s terminology of “authoritarian populism,” argues that the political regime manifests itself in opposition to same-sex marriage, abortion rights, and gender equality discourse.(Isabell Lorey, Democracy in the Political Present: A Queer-Feminist Theory (London: Verso, 2022).) Inciting moral panic through the themes of security, migration, and sexual liberalization is, according to Lorey, a means of authoritarian populism, which is reinforced precisely by the escalation of gender inequality and sexism. The attack on so-called gender ideology or genderism goes together with an attack on the rights of marginalized groups, including LGBTQIA+ people, women, and immigrants.(See for example: Petra Ďurinová, “Slovakia,” in Eszter Kováts and Maari Põim, eds., Gender as symbolic glue. The Position and Role of Conservative and Far Right Parties in the Anti-Gender Mobilizations in Europe (FEPS and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015), pp. 104–125; Benjamin D. Hennig, “Inequalities of Gender: Education, work, and politics,” Political Insight 10:2 (2018): pp. 20–22; Ľubica Kobová, “Co je antigender a proč se mu dnes daří?,” in M. Kos Mottlová, ed., Nebezpečná genderová ideologie v České republice? Monitorovací zpráva Social Watch o genderové rovnosti 2019 (Social Watch Česká republika, 2019): pp. 18–24; Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Korolczuk, Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment (New York: Routledge, 2022).) Feminist scholar Agnieszka Graff describes how the movement has even targeted gender studies and university programs because they were perceived as a source of so-called gender ideology. This affected, for example, the gender studies programs at Eötvös Loránd University and Central European University in Hungary in 2018, and the demand of the Ordo Iuris Institute in Poland directing public universities to provide a list of all male and female gender studies scholars in 2017.(Agnieszka Graff, “Anti-Gender Mobilization and Right-Wing Populism,” in Katalin Fábián, Janet Elise Johnson, and Mara Lazda, eds., The Routledge Handbook of Gender in Central-Eastern Europe and Eurasia (New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 266–276.) Although there was no outright withdrawal of accreditation of the gender studies program in the Czech Republic as in Hungary, gender studies were delegitimized as a useless field of study or framed as pseudo-scientific.(Kobová, “Co je antigender.”) Thus, authoritarian populism not only threatens LGBTQIA+ citizens and women for their gender and sexual identity, but also directly attacks researchers, publishers, gallerists, curators, and artists for their work and feminist views.

This ideological culture war and moral panic also manifests itself in political influence on contemporary art and in the desire to control the discourse and content of cultural production. Curator Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez argues that “we are facing the fact that neoliberal as well as extreme right-wing parties are becoming increasingly interested in contemporary art practices and funding, which for the last few decades was more a field of progressive leftist and socialist minds.”(Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, “Caretaking as (Is) Curating,” in Elke Krasny, Sophie Lingg, et al., eds. 2021, Radicalizing Care: Feminist and Queer Activism in Curating (London: Sternberg Press, 2021), p. 59.) When the Czech cultural organization tranzit.cz published a Czech translation of Sophie Lewis’s book Abolish the Family in 2023, a public reaction and several media articles followed in which the organizers were labeled “radical feminists” and the launch of the book a “controversial event.”(Eliška Fajmanová, “Stát dotoval akci radikálních feministek: Na knihu Zrušte rodinu přispěl 160 tisíci korunami,” CNN Prima News, October 7, 2023, https://cnn.iprima.cz/zruste-rodinu-kontroverzni-knihu-podporilo-ministerstvo-kultury-z-verejnych-penez-414230; Martina Sulovari, “Paradox: Radikálně kontroverzní kniha Zrušte rodinu byla financována státem,” Seznam Médium, October 7, 2023, https://medium.seznam.cz/clanek/martina-sulovari-paradox-radikalne-kontroverzni-kniha-zruste-rodinu-byla-financovana-statem-24707) Tereza Stejskalová, the director of tranzit.cz, believes that: “If we had published this book 5-10 years ago, it would have had no response. … In the 1990s, Valerie Solanas’ radical S.C.U.M (Society for Cutting Up Men) manifesto came out in Czech, and absolutely nobody addressed it then. The more polarized society becomes, the more art becomes a tool or a weapon.”(Tereza Stejskalová, interview by the author, email conversation, January 2024.) We are witnessing an intertwined global phenomenon where artistic practice and critical theory are appropriated by conservatives to defend national interests.

This is also the case in Slovakia, where—in November of 2023—newly elected Minister of Culture Šimkovičová objected to a painting by Slovak artist Andrej Dúbravský on view in the exhibition Ne(s)pútaní at the Galéria Slovenského Rozhlasu (the Slovak Radio Gallery). Šimkovičová expressed concern about the depiction of two naked men kissing in his painting, which she believes endangers children.(Jana Močková, “Umelec Andrej Dúbravský: Tu nejde o mňa, ale o to, že ministerka by chcela mať dosah na to, čo sa vystaví a čo nie,” DenníkN, December 3, 2024, https://dennikn.sk/3710557/umelec-andrej-dubravsky-tu-nejde-o-mna-ale-o-to-ze-ministerka-by-chcela-mat-dosah-na-to-co-sa-vystavi-a-co-nie/) The child protection narrative has already been used in Hungary to ban the expression and promotion of homosexuality to persons under 18,(See for instance: Lili Bayer, “Hungary LGBTQ community decries push to limit homosexuality displays,” Politico, June 11, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-lgbtq-community-limit-homosexuality-displays-viktor-orban/; “National Museum Director Fired for Failing to Protect Underage Visitors,” Hungary Today, November 6, 2023, https://hungarytoday.hu/national-museum-director-fired-for-failing-to-protect-underage-visitors/) and Šimkovičová’s clear homophobic position was also demonstrated in an absurd populist voting poll that appeared on the Slovak Ministry of Culture Facebook page that appeared as a reaction to the announcement of a clampdown on projects for the LGBTQIA+ community. The poll was presented as an opportunity for the public to choose allegedly democratically on how to redistribute the funding from the Department of Culture. The two options provided were: “A) Restoration of cultural monuments, preservation of cultural heritage and support for the artistic community. B) Support for LGBTI+ events where underage children learn to perform sexual performances; rainbow pride events where half-naked people perform in squares.” The poll’s choice of words clearly led voters to the first choice, and the anti-gender propaganda of the right-wing national culture explicitly presented LGBTQIA+ issues as a threat to children. (The poll has since been pulled from the Culture Ministry’s Facebook page, along with all other posts, with the statement that their social media is under constant “cyber-attack” since the new minister took office.) Narratives about harm to children were also used in Poland to censor Natalia LL’s Consumer Art (1973), among other works by Polish women artists, as a consequence of a letter from a visitor to the director stating that a visit to the National Museum in Warsaw had been a traumatic experience for her son.(Dorian Batycka, “Hundreds of Protesters Wielded Bananas After a Polish Museum Censored Feminist Artworks,” Hyperallergic, April 30, 2019, https://hyperallergic.com/497869/bananagate/) This resulted in a protest known as Jedzenie Bananów przed Muzeum Narodowym (Eating Bananas Outside the National Museum) in April 2019. Joanna Krakowska, and art historian and the protest co-organizer, comments that “the banana protest evoked not only the present context of Polish right-wing politics, [but also] the culture war that has been declared on art”.(Joanna Krakowska, “Eating Bananas Outside the National Museum: Unlimited Semiosis,” TDR: The Drama Review 65:4 (2021): pp. 131–146, here p. 132) Here we can observe exactly how closely artistic and cultural autonomy is intertwined with authoritarian populist rhetoric, how the control of the content of art becomes one of the first goals of such politics, and how these elements are intertwined with anti-LGBTQIA+ positions.

As highlighted above, the policy of the new Slovak government seems to follow the course already taken in Hungary by the Orbán government, which introduced a law banning the expression and promotion of homosexuality, which led to censorship of the content displayed in museums (and even self-censorship in advance to avoid any criticism by the government), the dismissal of museum directors, cordoning off part of a temporary exhibition depicting homosexual content, and the wrapping of books with LGBTQIA+ content in transparent foil.(Bayer, “Hungary LGBTQ community”; “National Museum Director Fired”; Bákro-Nagy Ferenc, Bozzay Balázs, and Andrea Horváth Kávai, “Hungary’s biggest book retailer considers removing all books with LGBTQ-related content from dozens of its stores due to anti-gay law,” Politico, July 20, 2023, https://telex.hu/english/2023/07/20/hungarys-biggest-book-retailer-considers-removing-all-books-with-lgbtq-related-content-from-dozens-of-its-stores-due-to-anti-gay-law ; Gergely Nagy, “Nem létezik olyan, hogy aberrált művészet, ilyen szólamokat Hitler fasiszta Németországában mondtak,” Quibt, November 17, 2023, https://qubit.hu/2023/11/17/nem-letezik-olyan-hogy-aberralt-muveszet-ilyen-szolamokat-hitler-fasiszta-nemetorszagaban-mondtak) Similarly, in the previous election period, the leading party in Poland (until the 2023 elections) Law and Justice (PiS) appointed preferred museum directors, censored artworks on display, and promoted Poland’s heroic history and citizenship through policies seeded with patriotism, protectionism, and restrictions on abortion rights.(Batycka, “Hundreds of Protesters Wielded Bananas”; Alex Marshall, “A Polish Museum Turns to the Right, and Artists Turn Away,” The New York Times, January 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/08/arts/design/poland-conservative-art.html; Taylor Dafoe, “The Longtime Chief of a Polish Modern Art Museum Has Been Unceremoniously Axed by the Country’s Right-Wing Government,” Artnet, April 28, 2022, accessed on 14 March 2024, available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world-archives/muzeum-sztuki-2106241; Ewa Majewska, Feminist Antifascism. Counter-Publics of the Common (London: Verso, 2021).)

Not only sexual minorities but also (im)migrants are positioned as a threat. The leader of the Slovak National Party (SNS), Andrej Danko made a statement arguing that we should not have “a dancer from Korea or conductors from abroad in the ballet when we have artists in Slovakia”.(Andrej Danko, in DenníkN, October 16, 2023, https://dennikn.sk/minuta/3629394/) While the Minister of Culture asserted that: “The culture of the Slovak people should be Slovak and no other”.(Šimkovičová, “Kultúra slovenského.”) In response to such explicitly nationalist and xenophobic statements, the Slovak-Vietnamese artist Kvet Nguyen says they make her fear for herself and her family. These statements “revive the overt xenophobia we know in stories from the 1990s; people who did not act Slovak (white) experienced physical and verbal attacks and were thus forced to leave the country. I fear that the policies of the current government are shaping Slovakia into a new country—one that people of my generation did not know but are slowly getting to know in a new light of nationalism. I regret this, because I feel that the destruction of everything that is not Slovak, according to those elected, will follow.”(Kvet Nguyen, interview by the author, email conversation, March 2024.) Cultural critic and anthropologist Ivana Rumanová argues that: “I currently see only two options—to fight or to emigrate (abroad or to another job).”(Ivana Rumanová, interview by the author, email conversation, February 2024.)

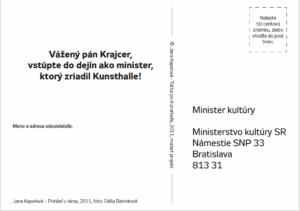

Jana Kapelová, Túžba po Kunsthalle (The Desire for Kunsthalle), 2011. Front of the postcard. Courtesy of the artist.

To return to the Kunsthalle Bratislava, with this contextual information in mind: the history of the institution is already fraught with conflict between the government and Slovakia’s cultural scene. The independent Kunsthalle Bratislava as a contributory organization of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic was established in 2021, but it had previously existed since 2014 in hybrid, non-independent forms as part of the Národné osvetové centrum (National Center for Education) or the Slovak National Gallery. When Kunsthalle Bratislava was established as an independent cultural institution in 2021, it was the result of the activities of the cultural initiative #stojimprikunsthalle (istandbykunsthalle), a non-profit civic and cultural initiative aimed at promoting the idea of the Kunsthalle’s institutional independence, which was supported by cultural practitioners, critics, artists, curators, and theoreticians. The art community in Slovakia has been calling for the creation of such an institution since the 1990s. In 2011, contemporary artist Jana Kapelová, in her participatory project Túžba po Kunsthalle (The Desire for a Kunsthalle), expressed the desire for an institution such as the Kunsthalle. In 2010, in the context of the initiative “Dvadsať rokov od Nežnej neprebehlo” (“Twenty Years Since the Velvet Revolution Did Not Happen”), artists and cultural workers organized a discussion with representatives of the Ministry of Culture regarding the existence of the Kunsthalle, where foreign guests were also invited to present their different models of operation and funding.(Jana Kapelová, interview by the author, email conversation, February 2024.) In the autumn of 2011, artists and critics actively communicated with the Ministry of Culture about the need for a Kunsthalle. The Minister of Culture at the time, Daniel Krajcer, decided—as a “Christmas present for the artistic community”—to instead contribute to the private non-profit gallery Danubiana, located twenty kilometers from Bratislava and founded thanks to the Slovak lawyer Vincent Polakovič and the Dutch patron and art collector Gerard Meulensteen. Moreover, after the announcement of the financial contribution, Minister Krajcer referred to Danubiana as the future Kunsthalle and Visual Arts Center.(Jana Močková, “Danubiana je múzeum, aké na Slovensku nemá obdobu – v dobrom slova zmysle, aj v tom zlom,” DenníkN, April 25, 2015,https://dennikn.sk/112584/kto-ma-zivit-krasku-na-dunaji/) This provoked a reaction from the artistic community art, which “staged a protest action of Christmas presents for the minister, in which they also took signed postcards to the office of the Ministry of Culture to show their disapproval.(Jana Kapelová, interview by the author.) Through postcards that were available in various galleries and cultural institutions, the general public could also participate in the project and send a postcard with a request for the establishment of the Kunsthalle directly to the Minister of Culture Krajcer.

Jana Kapelová, Túžba po Kunsthalle (The Desire for Kunsthalle), 2011. Back of the postcard. Courtesy of the artist.

Consequently, in 2011–2012, Kapelová prepared a six-channel projection entitled Kunsthalle–súhrnná správa o stave ustanovizne (Kunsthalle—Summary Report on the State of the Institution), in which a staged fictional polylogue of eighteen protagonists about their view on the processes of the creation of the Slovak Kunsthalle in the space of the House of Art was staged. The project included video documentation of interviews with political representatives (employees of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic), artists, theoreticians who have been active since 1997 in the question of the establishment of a state funded Kunsthalle and have participated in a positive or negative way in this ongoing project. Kapelová explains that: “During my research I began to see a cyclical narrative—at the beginning of the election period each government declared its interest in establishing an institution like the Kunsthalle, and at the end of the period they stated that it was not possible because the current situation did not allow for the establishment of a new contributory institution.”(Jana Kapelová, interview by the author.) This proves that the struggle for an institution representing contemporary art in its actual, non-static flexibility, heterogeneity, discursivity, and interconnectedness with contemporary theory and concepts that go beyond the national context has been very important for the Slovak cultural community for a long time. The ongoing struggle achieved its aims in 2021 with the establishment of the independent Kunsthalle Bratislava—but this struggle has been rekindled as the institution fights for is survival again today after only three years of its existence. Even though alleged irresponsible financial management of the institution was used as an argument for merging Kunsthalle with the Slovak National Gallery, an internal audit that took place at Kunsthalle revealed shortcomings of a primarily administrative nature, which the Kunsthalle had already addressed and corrected.

Jana Kapelová, Kunsthalle – súhrnná správa o stave ustanovizne (Kunsthalle—Summary Report on the State of the Institution), 2011-2012, Courtesy of the artist.

Although it is clear from the brief history outlined above that the establishment of a state-funded contemporary art institution in Slovakia has always been a challenge, the current situation is, however, specific in its “anti-gender ideology” focus. In their most recent book Who’s Afraid of Gender?, Judith Butler argues that anti-gender as a global phenomenon is a phantasmatic scene, in which gender “substitutes for a complex set of anxieties and becomes an overdetermined site where the fear of destruction gathers.”(Judith Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender? (New York: FSG, 2024), p. 10.) Therefore, the closure of Kunsthalle Bratislava as an independent institution by the current government is not necessarily due to its LGBTQIA+ programming per se, but rather due to a broader anti-gender discourse. All of the crises of today—economic, environmental and political—are obscured by the label “gender” and the fear-mongering surrounding it.

On March 27, 2024, the public’s last farewell with Kunsthalle Bratislava took place. At the event, entitled Kolektívne trúchlenie nad stratou Kunsthalle Bratislava (Collective Mourning for the Loss of the Kunsthalle), the Kunsthalle staff presented the activities planned for 2024 and, together with the teachers and students of the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, organized a farewell to the contemporary art institution. In addition to speeches, the performative event also consisted of a symbolic coffin made of cardboard with a white Kunsthalle inscription. Together with wreaths and candles, it was placed at the door of the ministry, then carried in procession in front of the entrance to the Ministry of Culture. After the ministry reported the act as a death threat to Minister Šimkovičová, a young student who co-organized the event (and had previously worked for the Kunsthalle) was summoned to the police and questioned. The government’s inability to critically decode signs, engage with facts, and seriously distinguish between truth and falsehood is also another problem associated with the current political regime, which subsequently responds with threats and intimidation.

Collective Mourning for the Loss of the Kunsthalle on March 27, 2024. Photo: Adam Balogh.

This retaliatory attitude can be seen in other government responses to the controversy over the new cultural policy. The cultural community in Slovakia organized a signature campaign in response to the events at the Ministry of Culture, in which they claim that the Minister of Culture “confuses the exercise of public office in a democratic and legal state with the autocratic exercise of power.”(“Otvorená výzva na odstúpenie ministerky Martiny Šimkovičovej,” https://www.peticie.com/otvorena_vyzva_na_odstupenie_ministerky_martiny_imkoviovej) On January 17, 2024, a public call for the Minister’s resignation was published, and on its closing date, January 26, 2024, the “petition” was signed by almost 190,000 people, making it one of the most successful signature campaigns in the history of the Slovak Republic. Ivana Rumanová, one of the initiators of the open call for the minister’s resignation, reveals that:

What makes us even more happy is that people from different regions and social groups have signed the appeal: we found a carpenter, a football player, a grocery owner, a surveyor, a top model… Academic institutions and professional associations from all over Slovakia have signed up to the call with their own statements. This response is a confirmation for us that the resistance to the incompetence and arrogance of power in the current leadership of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic has gone beyond the borders of the Bratislava cultural bubble. At the same time, I see this as a great chance to overcome some supposed and real elitism of contemporary art, which would be an excellent outcome of the whole initiative!(Ivana Rumanová, interview by the author.)

The Ministry of Culture first responded to the signature campaign by filing a criminal complaint with the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Slovak Republic (the police declined to file a criminal complaint and concluded that there were no grounds for prosecution in April 2024) and subsequently ignored the appeal, claiming that it was only public opinion and not a binding initiative. However, in response to the subsequent wave of solidarity that the petition provoked in the cultural community, the platform Otvorená kultúra! (Open Culture!) was created. Rumanová argues that “the sense of common threat has managed to bring the fragmented cultural community together and has accelerated the organization of the activism of different artistic genres and cultural sectors.”(Ivana Rumanová, interview by the author.) Open Culture! is a network of the Slovak cultural community whose aim is to act together in the name of protecting culture in Slovakia from the destructive actions of politicians.

It may sound pathetic, but we need to connect and be in solidarity and be able to sustain [ourselves in] the coming years. In addition to the drastic legislative changes that the Ministry is pushing through in a non-standard way by an expedited procedure, we also expect attacks on a personal level. It will be important, then, to stick together and not be intimidated. For now, it seems that much of the cultural community is able to put micro-conflicts aside and focus on joint strategic action. Which, until recently, was a utopia we could hardly imagine.(Ivana Rumanová, interview by the author.)

Rumanová argues that the polarizing rhetoric employed by the current Minister and the new government, is however “also that part of the artistic and cultural scene that accepts the division of people into ‘progressive’ and ‘backward.’ It is this dichotomy that brings the right and the extreme right to power; therefore, […] persistent[ly] questioning [this division] must be the main focus of resistance movements.”(Ivana Rumanová, interview by the author.) Comparably, Jana Kapelová argues that “In the last three years [the Kunsthalle] has closed in on itself, and while it has brought important contemporary discourse, it has forgotten about working with the general public, its founder, and about disrupting algorithms by explaining the content and formal metaphors of visual art. It contented itself with its existence and assumed that the audience would educate itself.”(Jana Kapelová, “Kunsthalle: cuo bono?,” Artalk, March 15, 2024, https://artalk.info/news/kunsthalle-cui-bono-1) These observations remind us of the importance of precision of dialogue and factuality of information that does not remain in a simplistic dichotomy of “us” versus “them,” in order to avoid perpetuating the same rhetoric used by authoritarian populism. Similarly, Butler argues that despite our differences of opinion, we need to remember the source of our oppression, which is not “gender” but rather social, economic, and environmental precarity. We need to “[find] ways to build alliances that allow our antagonisms to replicate the destructive cycles we oppose.”(Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender?, p. 264.)

Collective Mourning for the Loss of the Kunsthalle on March 27, 2024. Photo: Adam Balogh.

When Isabell Lorey asks whether we can imagine a social bond that does not diminish our caring, connectedness, and accountability, she proposes the concept of a “presentist democracy,” a framework that instead builds upon these aspects.(Lorey, Democracy in the Political Present.) As a form of solidarity and a force that emerged in response to the authoritarian rule over culture in Slovakia, Open Culture! demonstrates the power of art to challenge these narratives. The censorship and control of contemporary art and art institutions also shows us how much art matters, which also gives contemporary art the potential to challenge these nationalist, homophobic, and xenophobic narratives and create alternative discourses. Art theorist Carlos Garrido Castellano argues “for a long time [art constituted] an exclusionary field for a small group of initiates, [but here] art emerges here as challenging the economic and biopolitical contradictions of our reality”.(Carlos Garrido Castellano, Art Activism for an Anticolonial Future (Albany: SUNY Press, 2021), p. 259.) Commenting on the public performances organized in Brazil and Portugal, Castellano notes that these events “reveal the extent to which ‘art matters’ can constitute ‘social matters.’”(Castellano, Art Activism, p. 259.) Although the situation is critical, the Polish example gives us hope that civic activism and engagement can make a difference. The huge wave of pro-choice, anti-government protests and performative street actions since 2016 has shown the power of speaking out. The boldness, creativity and originality of these protests and events in Poland remains highly inspiring and highlights the importance of civic engagement in times of right-wing political change. As we witnessed in early 2024 when TV presenter Wojciech Szeląg apologized to the LGBTQIA+ community for the previous period of the right-wing PiS government and unacceptable statements against sexual minorities in Poland,(Ashifa Kassam, “‘This is where I apologise’: Polish state TV presenter says sorry to LGBT+ viewers,” The Guardian, February 13, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/13/polish-tv-presenter-apologises-lgbt-people-bart-staszewski) we can remain hopeful that artistic and civic activism will bring about positive change in the future in Slovakia too. In a climate of heightened focus on the heroism of national history and asserted notions of a victorious individual and collective national body, contemporary cultural production can perform an important function in challenging these narratives while contributing to the construction of an inclusive collective memory that empowers systematically marginalized individuals and communities.

The author would like to thank Nagy Gergely, Anka Herbut, Jana Kapelová, Martina Kotláriková, Kvet Nguyen, Ivana Rumanová, Agnieszka Sosnowska, Tereza Stejskalová and Krisztián Török, for their advice and the inspiring conversations that influenced this article.