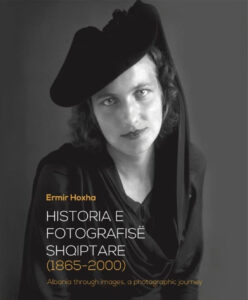

History of Albanian Photography (1865–2000)

Ermir Hoxha, History of Albanian Photography (1865–2000) [Historia e Fotografisë Shqiptare (1865–2000)] (Tirana: Albdesign, 2022), 245 pp.

Ermir Hoxha’s ambitious History of Albanian Photography surveys almost a century and a half of photographic practice in Albania, tracing the ways that foreign photographers pictured subjects in the present-day Albanian territories of Southeastern Europe (beginning in the 19th century) and the development of photographic studios in the Albanian nation-state in the early 20th century. It also chronicles the transformations in photographic paradigms that occurred under state socialism in the country (between 1945 and 1991) and the ways that both documentary and artistic photography responded to the first decade of the post-socialist transition in Albania. The book is divided into three chronological sections (1865-1900, 1900-1945, and 1945-2000), with each section further divided by chapters that are likewise mostly chronological in organization, dealing with the development of photographic practices in successive political regimes and social contexts in the country. Written in the Albanian language, the volume also features a brief closing summary in English, as well as short biographies (in Albanian) of the major photographers discussed in the text.(Unless otherwise noted, passages quoted in this review are translations by the author of the review.) Although structured primarily as a survey text for instructors teaching undergraduate students the history of Albanian visual culture, the book nonetheless boasts robust footnotes and bibliography, and—as the only comprehensive text on the subject—it will also serve as a vital reference for readers hoping to understand more about the art history of one of the least-studied nations in Southeastern Europe.

A professor at the University of Arts in Tirana, Hoxha is the author of several significant publications (in Albanian) on the history of art and architecture in the country. History of Albanian Photography follows his earlier expansive history of Albanian visual art published just a few years ago (History of Albanian Art (1858–2000)),(Ermir Hoxha, Historia e Artit Shqiptar, 1858–2000 (Tirana: Albdesign, 2019). Most recently, Hoxha is also the author of Socialist Realism in the Albanian Style: The Liberalization Period and the Communist Legacy in Albanian Contemporary Art [Realizmi Socialist në Stilin Shqiptar: Periudha e Liberalizimit dhe Trashëgimia Komuniste në Artin Bashkëkohor Shqiptar] (Tirana: 2023).) which included photography but focused primarily on painting, sculpture, and the graphic arts (as well as, in its final chapters, newer media such as video and installation).

History of Albanian Photography addresses a dearth of scholarship on Albanian photography, in any language.(There are few histories of Albanian art: even during the state socialist era, the first expansive history of Albanian visual arts, ancient and modern, was a two-volume study published at the end of the 1980s, co-authored by the well-known critic and art historian Andon Kuqali. (See Andon Kuqali, Historia e Artit Shqiptar, volume 2 (Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese e Librit Shkollor, 1988).) Photography in the country has been the subject of even fewer studies. With the exception of a books like Zef Paci’s study Marubi: Photography as Ritual (Tirana: Princi, 2012), and Luçjan Bedeni’s doctoral study on the Marubi (Foto-Studio ‘Marubbi’ Shpi Themelue në 1856, doctoral study, Qendra e Studimeve Albanologjike, 2021), most publications on Albanian photographers have been essentially albums, with little historical information beyond a basic introduction. (See, for example, Niko Xhufka: Ritme të Jetës Shqiptare (Tirana: 8 Nëntori, 1976), or Petrit Kumi: Jeta përmes Objektivit (Tirana: Ideart, 2013). Some assorted academic articles have looked at photography—especially in the late 19th and early 20th century—in Albania (such as Luçjan Bedeni, “Marubi Archive: Changing the History of Photography in Albania,” Post: Notes on Art in a Global Context, September 25, 2019, https://post.moma.org/marubi-archive-changing-the-history-of-photography-in-albania/), and one study has been published on the photography that appeared in Ylli (The Star), the full-color magazine produced in state socialist Albania (Anouck Durand and Gilles de Rapper, Ylli: les couleurs de la dictature (Autoédition, 2012).) This lacuna is particularly unfortunate given the centrality of photography to post-socialist and contemporary artistic practices, and the increasing attention to the country’s photographic archives, evidenced by the opening of the Marubi National Museum of Photography in 2016, in Shkodra—and its ongoing digitalization of the archive of the Marubi Photothèque and other early photography studios—as well as recent digitalization initiatives such as Fototeka, helmed by the Art & History Foundation and funded by the Albanian Ministry of Culture.(See https://fototeka.al. The project is directed and curated by Rubens Shima, one of the former directors of Albania’s National Gallery of Arts.) At the same time, a number of recent exhibitions and publications have looked at foreign photographers who visited Albania in the late socialist and early postsocialist years and documented what they saw—the exhibition Flashback: Albania in the 90s with photos by Robert Pichler (held in 2019 at the National History Museum) and The End. The Beginning: Albania 1981–1991 with photos by Michel Setboun (held in 2018 at the Center for Openness and Dialogue) being just two examples.

History of Albanian Photography addresses a dearth of scholarship on Albanian photography, in any language.(There are few histories of Albanian art: even during the state socialist era, the first expansive history of Albanian visual arts, ancient and modern, was a two-volume study published at the end of the 1980s, co-authored by the well-known critic and art historian Andon Kuqali. (See Andon Kuqali, Historia e Artit Shqiptar, volume 2 (Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese e Librit Shkollor, 1988).) Photography in the country has been the subject of even fewer studies. With the exception of a books like Zef Paci’s study Marubi: Photography as Ritual (Tirana: Princi, 2012), and Luçjan Bedeni’s doctoral study on the Marubi (Foto-Studio ‘Marubbi’ Shpi Themelue në 1856, doctoral study, Qendra e Studimeve Albanologjike, 2021), most publications on Albanian photographers have been essentially albums, with little historical information beyond a basic introduction. (See, for example, Niko Xhufka: Ritme të Jetës Shqiptare (Tirana: 8 Nëntori, 1976), or Petrit Kumi: Jeta përmes Objektivit (Tirana: Ideart, 2013). Some assorted academic articles have looked at photography—especially in the late 19th and early 20th century—in Albania (such as Luçjan Bedeni, “Marubi Archive: Changing the History of Photography in Albania,” Post: Notes on Art in a Global Context, September 25, 2019, https://post.moma.org/marubi-archive-changing-the-history-of-photography-in-albania/), and one study has been published on the photography that appeared in Ylli (The Star), the full-color magazine produced in state socialist Albania (Anouck Durand and Gilles de Rapper, Ylli: les couleurs de la dictature (Autoédition, 2012).) This lacuna is particularly unfortunate given the centrality of photography to post-socialist and contemporary artistic practices, and the increasing attention to the country’s photographic archives, evidenced by the opening of the Marubi National Museum of Photography in 2016, in Shkodra—and its ongoing digitalization of the archive of the Marubi Photothèque and other early photography studios—as well as recent digitalization initiatives such as Fototeka, helmed by the Art & History Foundation and funded by the Albanian Ministry of Culture.(See https://fototeka.al. The project is directed and curated by Rubens Shima, one of the former directors of Albania’s National Gallery of Arts.) At the same time, a number of recent exhibitions and publications have looked at foreign photographers who visited Albania in the late socialist and early postsocialist years and documented what they saw—the exhibition Flashback: Albania in the 90s with photos by Robert Pichler (held in 2019 at the National History Museum) and The End. The Beginning: Albania 1981–1991 with photos by Michel Setboun (held in 2018 at the Center for Openness and Dialogue) being just two examples.

The first section of Hoxha’s book details the establishment of the Marubi photo studio (which Hoxha argues began its commercial activities in 1865, rather than the oft-cited dates of 1856 or 1858).(Bedeni dates the beginning of the studio to 1858; see Bedeni, “Marubi Archive.” Paci’s study, from 2012, cites the founding as 1856, based on the fact that one of the subsequent directors of the studio used that year on publicity materials. See Paci, pp. 31-32.) Founded by the Italian-born Pjetër Marubi (Pietro Marubbi) in Shkodra, in the north of Albania, the studio would later be passed down through multiple generations. Other important photo studios would be set up by students of the Marubi studio, such as Kolë Idromeno, the well-known architect and painter, who established Dritëshkronja (“Writing with light”) in Shkodra in 1884. (p. 33) The photos created by Pjetër Marubi may seem like orthodox portraits, peoples by motionless figures placed firmly in the middle of the frame, but the photographer’s interest in documenting sitters from all walks of life—from beggars crouched in the courtyard of the photostudio to aristocrats dressed in national costume—emphasize photography as a tool of social realism. Some of Idromeno’s photos, by contrast, were created as studies for paintings: here, half-naked figures that would later appear in cautionary religious paintings such as False Testimony or The Illicit Marriage lurch and contort, with ghastly and cartoonish expressions.

The second section of the book follows the development of the Marubi studio under Kel Marubi (born Kel Kodheli, who took over the studio from Pjetër), and then under his son Gegë Marubi, as well as the establishment of Kristaq Sotiri’s photo studio in Korça in 1923, after the artist returned from his studies in the United States. (pp. 66-67) Hoxha argues that Sotiri’s work represents a new approach to photography, and specifically to portraiture (still the primary function of the Marubi studio and others at the time), injecting an emphasis on individual psychology over social and ethnographic interests. (p. 67) This second section also analyzes the increasing dissemination of photographs first under the reign of King Ahmet Zogu and later under the Italian fascist occupation, tracing how photographs circulated on the increasing number of postcards, and cultural and political publications, published in these years.

For readers of ARTMargins Online, it is the third section of the book, dealing with the postwar period, that holds the most interest, and as such it is my focus here. Hoxha describes the shift in photographic practices that accompanied the rise to power of the Albanian Communist Party (from 1948 onwards, the Albanian Party of Labor)—a shift that, he argues, was characterized by the prioritization of propaganda images and the adherence to a relatively limited set of themes, resulting in “cliché black and white images.” (p.128) He also traces the centralization of photographic production, and photographic archives: the Ristani studio in Tirana was the first to be made part of the state, but the symbolic culmination of the state’s takeover of photography was the 1970 establishment of the Marubi Photothèque, an institution that consolidated the archives of several other early photo studios. (pp. 125-126)

Hoxha’s text focuses on highlighting the key photographers at work in Albania in a given historical period, but this emphasis comes at the expense of delving into the images: the book is richly illustrated, but there is not much visual analysis of the included photographs. This is regrettable because there are interesting formal questions to be asked. In fact, Hoxha quotes from his own interview with the well-known photographer Petrit Kumi (who worked for the prestigious Ylli (The Star) magazine, and who was one of the first people to write on photography as an artistic form, as opposed to a craft (p.140), wherein Kumi explains that it was foremost “photographic forms” that “were borrowed from imported magazines like Sovetskoe Foto, but also Czech, Polish, and Hungarian magazines…because they were the product of a more advanced culture in terms of visual art.” (p. 131) But what exactly were these forms that were borrowed? Might they explain the dramatically oblique points of view, or the darkened silhouettes of workers thrown into sharp contrast against factory architecture and the fragmented geometry of power transmission poles that often appear in the images of Kumi and Niko Xhufka? The tight cropping of scenes of labor taking place on railroads and in factories, where the human body seems to activate converging nexuses of lines and colors?

The formal resonances of these borrowings would be particularly interesting to examine, even if only speculatively, precisely because Hoxha argues that until the 1970s (and even then), Albanian photography occupied such an uncertain position in relation to the other visual arts (especially painting and sculpture). (p. 162) Early commentators in the 1930s, including sculptor Odhise Paskali and the Franciscan friar and poet Gjergj Fishta, saw photography’s overly direct imitation of nature as evidence that it was a skilled trade rather than an art form. (p. 45) Later, during state socialism, there was no designated path to studying or practicing photography (photographers with specific artistic training often studied painting in the “Jordan Misja” Artistic Lyceum in Tirana, and sometimes in the Higher Institute of Arts), and photography was rarely a priority in the early discussions held by the Union of Writers and Artists of Albania. (p. 162)

This changed in the 1970s, when the Union opened an office specifically for the commission of “artistic photographs.” (p. 162) In the mid-1960s, Ylli had opened a competition for documentary photography, but by the ‘70s, a generation of photographers that included Petrit Kumi, Niko Xhufka (who worked for the main daily newspaper, Zëri i Popullit (Voice of the People)), Pandi Cici, and Pleurat Sulo were creating images that clearly departed from straightforward documentary modes. The question that Hoxha suggests obliquely, but does not raise or investigate directly, is whether the relatively peripheral position of photography in fact allowed it to be more formally adventurous than painting or sculpture. Many of the debates against formalism and modernist influence in Albanian art in the 1970s focused on color, and the painterly treatment of forms,(On these debates, see Raino Isto, “‘This Exhibition Will Go Down in Our History’: Art Exhibitions in Albania around 1972 and the Promise of Spring,” Art Studies/Studime për Artin 21 (2023): pp. 89–135.) and as such the relatively avant-garde (black and white) compositions of photographers like Niko Xhufka (whose works contained sharp contrasts creating psychologically ambiguous scenes, disconcerting perspectives, and sometimes almost completely abstract aerial images) were not the subject of sustained critical scrutiny.

This is not to say that photographs were not carefully policed in state socialist Albania: Hoxha examines the practice of retouching and altering photographs (widespread across the socialist world), especially the removal figures with problematic political backgrounds, whom the dictator Enver Hoxha had decided to purge. (pp. 182-185) The state socialist concern about photography’s indexical character, and thus its truth value, has been explored by others.(See, for example, Leah Dickerman, “Camera Obscura: Socialist Realism in the Shadow of Photography,” October 93 (Summer 2000): pp. 138-153.) What is most potentially interesting in this case is the way that the concern with truth primarily limited itself to which historical figures were featured in an image, leaving aside concerns about whether or not the formal structure of the image might resemble modernist experimentation—something that was, from 1973 onwards in Albania, officially prohibited and sometimes resulted in serious consequences for artists.

The final chapter of the third section of Hoxha’s survey looks at photography in the final years of state socialism (the late 1980s) and the so-called transition years, the decade of the ‘90s. Here, as in the earlier chapters of the book, Hoxha looks at how both foreign photographers and Albanians pictured the end of socialism and the socio-economic changes that came after 1991. Unfortunately, Hoxha tends to treat images created by foreign photographers visiting state socialist Albania as inherently more “true” than images produced by photographers working in the socialist system. For Hoxha, the works of photographers like Ferdinando Scianna (from Italy) or Robert Pichler (from Austria)—who visited Albania in the late socialist 1980s or the early postsocialist 1990s—reflect a blunt look at “a system in collapse,” at “the poverty of the Albanians in the last years of a political and economic crisis.” (p. 195) He does not consider that these photographs of poverty and rural life by Western photographers had their own role to play in presenting the social and economic project of communism as a definitive failure (to both Western and Eastern audiences), justifying the need for policies like shock therapy and political intervention.

The 90s saw both experimentation on the part of Albanian photographers and the further institutionalization of photography as an art form in Albania, with the establishment of the “Gjon Mili” Society of Albanian Photographers in 1991, the creation of the Fotografia Art newspaper in 1996 by Besim Fusha, and the founding of the “Marubi” prize and International Exhibition of Artistic Photography in 1998. (pp. 206-208) Hoxha’s chronology of these events is helpful, but the reader again misses a more critical engagement with the images produced in this period. For example, Hoxha notes the turn towards the nude, as a response to its prohibition under state socialism. But the majority of the nude photographs created during this time are erotic images of nude women photographed by male photographers, a concise example of the pervasive patriarchal structures that continued in Albanian art even after the end of state socialism. The exceptions are works by women like Rudina Memaga or Silvana Nini—which are notable precisely for the way they deny the direct gaze upon the nude female body, obscuring it behind reflections or veils. (pp. 209, 212) Despite having explored the patriarchal implications of photographers like Pjetër Marubi creating images of bare-breasted beggar women in the first section of the book (p. 26), here Hoxha is less willing to call out the power imbalances that structure access to and representation of the body—nude or otherwise. A more sustained look at how these particular images speak to their political and cultural context might have yielded more interesting questions for future researchers about the changing role of photography in the transition years.

This unevenness in how closely Hoxha’s text looks at the photographs it discusses is one of the book’s disappointments. It often seems that photographs representing completely different approaches to the process of picture-making (like Leon Çika’s Nude and Bevis Fusha’s Hiding, both from 2000) are reproduced, and their makers mentioned in close proximity, without an exploration of what the differences between the images mean. (pp. 210-211) In the first of these photos, nearly the entire (black and white) picture is taken up by the silhouette of a woman’s bare breast and arm, against the stark lightness of sheets behind her. In the second, a group of a group of people—clearly working class or underclass—stand under the glaring sun in a refuse dump on the periphery of a town or city, each on suddenly moving to obscure their face with whatever they have to hand, rejecting the photographer’s gaze. Surely these differences reveal important tensions, conflicting notions about who is able to look, and how they can look, that participate in the restructuring of postsocialist subjectivities.

Ultimately, though. the lack of critical engagement with the visual qualities of so many the photographs presented must be weighed against the book’s overall contribution: that it offers a clear and careful chronological introduction to photography in a country that still suffers from a dearth of academic publications on its art and visual culture. Without this foundational kind of work—which aims to highlight key artists and illuminate trajectories of artistic practice over time—it is hard to ask more detailed questions, ones that will delve into the specifics and contradictions of aesthetic shifts, biographies, and the plethora of meanings that photographs can present.

Hoxha’s book does not aim to actively situate itself in dialogue with other scholarly studies of photography in the former socialist world, which is understandable given the publication’s primary character as a general survey. However, one hopes that the future scholarship that books like Hoxha’s enable will more robustly engage with a transnational perspective—not just by examining how foreign photographers saw Albania (there is much attention to this in Hoxha’s book), but also by charting how the function of photography in Albania parallels or diverges from trajectories in the rest of the socialist and postsocialist world. The richly illustrated character of the book will allow readers beyond the Albanian-speaking world to expand the geographic scope of their knowledge of photography as a reflection of social change in the region, and—for scholars and curators—the book’s admirably complete chronology of key artists, studios, and events will no doubt prove useful for comparative studies.