The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing

“The grave is better than not knowing”: this is how Kumrije Jahmurataj expressed her sorrow while anxiously awaiting news of her missing husband, Smajli, who to this day remains unaccounted for after the 1998-99 Kosovo War. Jahmurataj was interviewed as part of research conducted by The Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo (HLC Kosovo), a non-profit organization that was first established during the social upheaval of 1997, before the war began. In the post-war context, HLC Kosovo has played a key role in addressing war crimes by implementing transnational justice mechanisms and recommending policies for juridical processes.(In addition to political and legal efforts, HLC Kosovo has undergone initiatives exploring alternative methods of understanding the past in a historical continuum encompassing the genocide and destruction that fundamentally changed the course of life for Kosovars. See: https://www.hlc-kosovo.org/index.php/en/publications.) The conflict in Kosovo resulted in the killing of more than 13,000 people, and over 4,000 disappearances, between 1998 and 2000. Despite continuous investigations, as of today, there are still 1,620 persons missing.(“Kosovo Wartime Victims: The Quest for Justice,” U.S. Government Publishing Office, April 30, 2019, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-116hhrg36132/pdf/CHRG-116hhrg36132.pdf.) Despite a large number of persons still unaccounted for, the rhetoric employed in ongoing political dialogues between Kosovo and Serbia aims primarily to achieve a normalization of relations between the two countries, and in doing so these discourses have treated the missing people and other victims of the war as impersonal data, neglecting their long-suffering families.(The political dialogue between the two countries often referred to as the Brussels Dialogue, started in March 2011 and is facilitated by the European Union. The first phase of the political dialogue focused on reaching agreements on “technical” matters including energy, freedom of movement, education, insurance, and telecommunications amongst others. The second phase started in 2013 and was centered around “political” agreements that aimed to contribute to further normalization of the relations between the countries and resolve the war disputes. This phase involved negotiations regarding territory and mutual recognition. However, many of these agreements were never implemented as the Serbian government continues to deny the independence of Kosovo and refuses to take responsibility and action to ensure justice for the committed war crimes. For more, see Donika Emini and Isidora Stakić, “Belgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalization?”, available online at https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief%205%20Belgrade%20and%20Pristina.pdf. Currently the representative of Kosovo in the Brussels Dialogue is the prime minister Albin Kurti from the political party Self-Determination, who in the talks that took place in May 2021, addressed the issue of the missing people, and required the Serbian leaders to recognize, and deal with the past for fruitful dialogues that have equal reciprocity. Xhorxhina Bami, “Serbia, Kosovo Leaders Cross Swords at Second Meeting,” Balkan Insight, July 19, 2021, https://balkaninsight.com/2021/07/19/serbia-kosovo-leaders-cross-swords-at-second-meeting/.)

Ms. Jahmurataj’s statement serves as the title to the exhibition by the Kosovar artist Driton Selmani, curated by Prishtina-based artist and curator Blerta Hocia, commissioned by the HLC Kosovo. The exhibition—installed at the Palace of Youth and Sports in Prishtina—explores the notions of absences and remembering, and examines how such subtle issues can be humanized by creating space for sentiments that have been stripped out of political discourse.

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

In doing so, the exhibition forms part of a broader effort to commemorate conflicts and traumas of the recent past in Southeastern Europe and beyond, particularly those that belong to the postsocialist period. Such efforts often bring together artists and non-profit organizations, and likewise often function as a corrective to international policies, which tend (as in the case of Kosovo and Serbia) to prioritize political stability over the need for individuals or families to grieve, to have their losses openly recognized, and to have their voices amplified over politically saturated narratives. To achieve this, The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing focuses on creating a sacral space—one that encourages calm reverie—that nonetheless registers a compounded sense of unease and a lack of closure through the juxtaposition of data (names, dates, and the marked passage of time) with the painful truth about the missing people and lived experiences of such losses. The show is key for generating discussions around the cultural institutional endeavors (or lack thereof) that critically grapple with these issues. In the context of Kosovo, the exhibition can be seen as part of the increasing recognition, elaborated further later in the review, of the aid art provides in commemorating and memorializing losses, and in acknowledging the ramifications of the war. The role of artists in examining these issues is particularly important since there is no official museum or institution that carries out a mission to interpret the Kosovo War and reflect on the traumas manifested in its aftermath.

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing is installed at the Palace of Youth and Sports, a building whose multifunctional character—coupled with the lack of appropriate, dedicated institutions that might otherwise host such events—has allowed it to contribute significantly to many different developments in culture in Kosovo. On the second floor, the building’s vestibule has been transformed in order to direct visitors down a long, narrow, white tunnel in which both sides of the wall are covered in sheets of paper holding information about the 1,620 people who went missing during the Kosovo War.(The entrance is reminiscent of the preceding 2019 exhibition organized by HLC Kosovo, Once Upon a Time, Never Again, also curated by Blerta Hocia, which presented artifacts and memorabilia of children killed during the war along with commentary from the victim’s families. Both exhibitions are characterized by the same curatorial approach, that of naming lost identities before the viewer reaches the objects. Once Upon a Time, Never Again remains open at The Documentation Center Kosovo. Once Upon a Time and Never Again, ed. Blerta Hocia, (Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo, May 13, 2019) exhibition catalog, https://www.hlc-kosovo.org/storage/app/media/Katalogu%20digjital/HLC-BOOK-NOV23112020-DIGITAL.pdf.) The sheer length of the hall and mass of papers effectively evoke the scale of these losses. Yet the hall’s ultimate feeling of hopefulness, alluded through its brightness, is reinforced when one stumbles upon an empty spot where an piece of paper once stood. The page was removed from the wall as Nuredin Dvorani was identified and reburied on January 21, 2022, in the village of Tërstenik, Drenas.

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

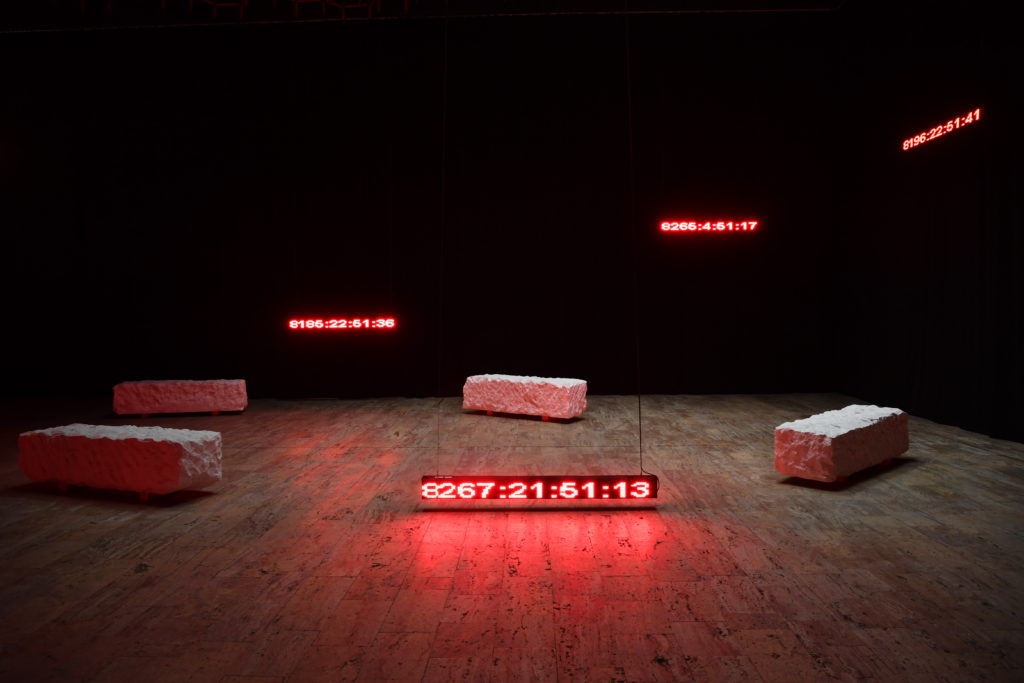

The hallway’s brightness and narrowness give way to a strikingly different environment: a vast void whose darkness initially obscures the objects within. The centerpiece of the exhibition is a series of ten roughly-carved rectangular stones that uncannily resemble coffins, which create a cemetery-like setting. The darkness and stones imbue a sense of sacredness, creating an intimate space for rumination. Twelve digital clocks (equal to the number of hours shown by an analogue clock) are dispersed throughout the room; a few are placed among the stones and the rest are suspended, floating in the darkness. Their large, red blinking displays show a running count of the number of days, hours, minutes, and seconds that have passed since the recorded times of twelve different reported disappearances. Navigating through the space, one observes how different notions of time intersect and create discomfort: there is the long passage of time connoted by the stones, the time running on the digital clocks, and finally, the unfolding of experiential time perceived differently by each individual visiting the exhibition. The temporalities and spatialities of the exhibition as a whole offer a place to grieve, mourn, remember, or come to terms with such absences. Absence is a feeling that anchors the exhibition: a palpable sense of loss emanating through the space invites visitors to both ponder their own losses and reflect on the impossibility of reckoning with the weight of certain losses.

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

After viewing the exhibition in Prishtina, I met with the artist Driton Selmani. “I wanted to create a language that, in one way or another, doesn’t recognize the normativities of political language,” he explained.(Conversation between the author and Driton Selmani, Prishtina, January 2022.) Inevitably, our discussions revolved around the role of art speaking with and to such events. Selmani—who experienced the Kosovo War himself—asserted that for him it was crucial to undertake this project in collaboration with HLC Kosovo so that his conceptual framework would be grounded in documents, interviews, memorabilia, footage, and other materials that are a testimony of the war. His practice draws attention to the in-depth research and sensitivity required when responding to and posing questions about others’ lived experiences.

Mapping out the process that led to the development of the work, Selmani started by listing: data, the people he met, emotions and narratives he accounted for, research, locations, and unexpected encounters. While speaking, he unconsciously drew an incomplete but composite algorithm whose solution is yet to be found; analogous to the situation and process of work still to be done in the case of irrevocable human absences. The extensive research that informed the conceptual underpinnings of the show transpires in a direct form only through the reference in the title, and index cards, each of which contains detailed information about the missing people including, name, gender, date of birth, place of birth, place and district of disappearance, and date of disappearance.

“It is a place of repose for visitors and a reflection on this huge flame that continues to incinerate many souls,” observes Selmani.(“The exhibition Grave is Better Than Not Knowing is now open,” Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo, https://www.hlc-kosovo.org/index.php/en/media/news/95/exhibition-grave-better-not-knowing-now-open.) Alas, certain flames might never burn out for those families whose loved ones might have their incinerated remains in the morgue of Kosovo with no chance left for identification, leaving many questions eternally unresolved. What can be done to prevent the incineration of memory? Can art intervene in such dire circumstances and heal wounds that are further deepened by the absence of acknowledgment by the aggressor?(“Vucic Denial of Recak Massacre Sparks Outrage in Kosovo,” Prishtina Insight, December 6, 2019 https://prishtinainsight.com/vucic-denial-of-recak-massacre-sparks-outrage-in-kosovo/. ) On the constitutive limits of memory, archival materials, and narratives that cannot be retrieved, the author Saidiya Hartman writes: “My effort to reconstruct the past is, as well, an attempt to describe obliquely the forms of violence licensed in the present, that is, the forms of death unleashed in the name of freedom, security, civilization, and God/the good. Narrative is central to this effort because of ‘the relation it poses, explicit or implied, between past, presents and futures.’ […] How can a narrative of defeat enable a place for the living or envision an alternative future?”(Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): pp. 1-14, muse.jhu.edu/article/241115.) Selmani’s exhibition is not representative of one specific narrative; rather it successfully operates as an alternative place that allows each visitor’s idiosyncratic experience to resonate and engage in the present with a past that in many ways is denied. Selmani effectively combines field research with artistic imaginaries to subvert the incessant state of invisibility and powerlessness that governmental apparatuses generate. Defined by the unknown and uncertain, erasure, and the intense present, all exhibition components poignantly reflect on the experiences of those families who continue to live with the agony of injustice.

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

Although Selmani claims that the commission of the HLC Kosovo was decisive in his decision to embark on this exhibition, his critical engagement with the ramifications of war is not unanticipated. It can be seen as a logical continuation in the investigations that Selmani—as a post-war artist—has carried out in his earlier works, questioning the politics of identity, belonging, and displacement. Produced earlier in his career, Tell Me Where I Am From? (2012), for example, consists of a series of drawings of Kosovo’s map as known and imagined by his classmate. The work was conceived during his studies at Arts University Bournemouth after realizing that Kosovo was often expunged from the maps, texts, and lists of countries he came across in daily life. Juxtaposing political and personal stances, the drawings were presented together with a reference map of Europe embroidered by his mother, in which Kosovo’s surface is visualized with the pattern of the sea. In another work, following the same conceptual line, the words of the title I, Why, Why? (2012) are embroidered on a white background, again produced collaboratively with his mother. The embroidered phrase raises questions around identity through the use of double-entendre, as the pronunciation of the word “why” in Albanian, sounds like “vaj,” meaning to lament. For the 10th anniversary of Kosovo’s independence, while political disputes raged over which flag—Kosovo’s or Albania’s—should be hung in what is known as the ‘flag roundabout’ in Prishtina, Selmani disrupted the situation by illegally replacing the Albanian flag with an offside flag used in football games. The work, titled Red Tape (2018), was a bold, thought-provoking intervention that questioned the state’s systemic employment of nationalist and populist rhetoric at the forefront of every situation.(Hidden in Plain Sight, ed. Lora Sarisalan (sbunker, 2021), exhibition catalog.) Theorist Sezgin Boynik writes that this work asks, “What are the invisible sources of incessant nationalism if not the same as the structures that are reproducing the semi-comprador bourgeoisie operating secretly inside the state?”(Sezgin Boyink, “ A Personal Account of Nationalism and Art in Kosovo” in Notes on Contemporary Art in Kosovo, ed. Katharina Schendl (Sternberg Press, 2018), pp. 55-68.) The gesture was met with significant backlash for Selmani, making him rethink the notion of flags as connected to the nation-state for the majority of the population.

The themes and ideas addressed by Selmani are omnipresent in the work of Kosovar artists. The socio-cultural development of the country has brought agency within the cultural scene, and empowered artists to tell and contextualize their own histories and narratives within broader discourses of the art in the region and globally. This shift becomes especially evident if we conduct a comparative analysis of art produced in the late 90s and early 2000s, which did not manage to escape the interpretive framing of nationalism—a particularly recurring approach in the international presentations.

However, galvanized by the passing of time and the need to salvage lost memories and experiences, the last few years have witnessed what we can interpret as a new wave of war-related art projects from Kosovar artists. I would argue that these artistic subjectivities are a reflection of cultural dynamics and a civic transformation that has created conditions of being in a safe place that allows us to pose questions about the past and imagine better futures. Some examples include the representation of Kosovo at the Venice Biennale in 2017, for which the artist Sislej Xhafa presented the installation Lost and Found, a reflection on the perpetual consequence of war and the delayed injustice for the 1,664 people missing at the time.(love you without knowing, ed. Jérôme Sans (National Gallery of Kosovo, July 5- August 25, 2017), exhibition catalog.) In the next edition of the biennale, the pavilion of Kosovo again revolved around the period of war through a three-channel video installation titled Family Album (2019), created by the artist Alban Muja. The video displays narrations from the protagonists of four highly publicized photographs from the war who shed light on how reality is permeated and mediated by visual images.(Ëremirë Krasniqi, “Alban Muja,” Artforum, January 2022, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/202201/alban-muja-87500.) During the last year, the artist Petrit Halilaj opened his exhibition Very Volcanic Over this Green Feather at Tate St Ives reflecting on the trauma of war by probing his personal history to question “how, and by whom, narratives around personal and cultural identity, heritage and memory are preserved fabricated, altered or destroyed.”(Very volcanic over this green feather, ed. Anne Barlow and Giles Jackson (Tate, October 16, 2021- January 16, 2022), exhibition catalog.)

Driton Selmani, The Grave is Better than Not Knowing, 2021. Installation view. Photo by Atdhe Mulla.

At the end of 2021, the country’s main public cultural institution, the National Gallery of Kosovo (NGK), presented the survey exhibition Parallel, in which the artist and politician Eliza Hoxha commemorates today’s freedom by remembering the families of missing persons and victims of sexual violence, and presented a personal journey and interpretation of the 90s before the culmination of the war. Despite the similarities in their general aims, the underpinnings of all these projects differ, as some of them examine these subjects based on their own lived experiences while others tackle the issues from the position of a witness. Moreover, it is important to observe how these projects have contributed to changing the discourse, and offered alternative perspectives for remembering and healing—which they have done by denouncing what the state apparatus and the international missions in Kosovo have failed to achieve. For instance, although The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing and Parallel were staged at the same time, the former exhibition was commissioned and further supported with research by HLC Kosovo, an organization with the legitimacy of representation that engages closely with people affected directly by these issues. As such, it generated an instructive discourse and critique, and elicited stronger reactions from the general audience, compared to the exhibition Parallel at the NGK. Besides receiving no reviews, Parallel was closed for most of its duration due to the pandemic restrictions, and it did not seem to have a specific purpose within the larger annual program of the NGK, whose role in the show seemed to provide the space more than making an insightful and critical contribution.

In totality, the gradual proliferation of projects and exhibitions devoted to the memory of the war effectively demonstrate individual resilience while also drawing political attention to the unresolved issues at stake. The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing is part of a broader movement in Southeastern Europe, to openly confront the conflicts that took place after the end of state socialism and the breakup of Yugoslavia by creating spaces that recognize that the effects of events like the Kosovo War still shape the lives and experiences of thousands. It also reflects an artistic shift away from the framework of nationalism and towards an emphasis on creating places and spaces where the multitude of narratives about war can come together. These shifts in art and memory discourses also demonstrate the need for a dedicated museum of the Kosovo War, an institution that could reconstitute these narratives and present others that have been omitted. As mentioned earlier in this text, The Grave is Better Than Not Knowing was installed in a multifunctional space, the Palace of Youth and Sports. The multifunctionality of the place is not necessarily something to be celebrated. Rather, it should serve as a call to cultural institutions of Kosovo to reflect on their own ineptitude in generating a sustained discourse about the legacy of the war. It shows the critical need for a museum with a dedicated space devoted to the war, and the important role that such a museum would play for the Kosovar society.

This article is part of the Special Issue Contemporary Approaches to Monuments in Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: