The Seductiveness of the Interval at the Renaissance Society (Exhib. Review)

Stefan Constantinescu, Andrea Faciu, Ciprian Muresan, and studioBASAR. The Seductiveness of the Interval, The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, Co-organized with the Romanian Cultural Institute

Alina Serban, curator, May 2-June 27, 2010.

The interval, more than just an empty, liminal space, allows for a gooey, messy mélange of works that are at once sensuous, affective, and intimate, while pointing to the harsh realities of a world plagued by hope at the same time as despair. The artists featured in this exhibition are also stuck in an interval: they are old enough to have come of age during Communist Romania, but also young enough to experience the aftereffects of the country’s rupture with the past and the transition to its democratic present.

In her catalogue essay, “Hello. Excuse Me,” Katalin Timar prefers to discuss the interval in terms of its musical connotation, espoused most lucidly by Jean-Luc Nancy as the “new” note produced when two distinct chords are played at once.(Jean-Luc and Laurens Ten Kate Nancy, “Cum’…Revisited: Preliminaries to Thinking the Interval,” in Intermedialities, ed. E. Ziarek and H. Oosterling (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010).) This lyrical interpretation of the interval is reflected in Seductiveness to varying degrees bythe five works in the exhibition. The works in Seductiveness are trapped, perhaps haunted, in terms of the interval where they reside between the constant back and forth between the universal and the specific, between lyricism and dry conceptualism. Although these works oftentimes refer to specific political and historical events, these references tend to be buried.

However sensuous and affective the individual works, the curatorial strategy behind this exhibition brings up a strange brew of questions regarding the global export of art. For this exhibition, the entire Romanian Pavilion from the 2009 Venice Biennale was transported to to the Renaissance Society in Chicago, physically realizing the model of art-as-export on a grand scale. Obviously, the constant circulation of artworks into museums, galleries, and other venues through the mode of (re-) exhibition is nothing new. Even entire exhibitions themselves have been restaged. The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavilion installed at the Art Gallery of York University (Toronto) comes to mind, or Marina Abramovic’s re-performances of her work. This follows a compelling trend in curatorial practice: that of historicizing the art exhibition as an event rather than an invisible skeleton that supports and props up individual artworks. What makes the Renaissance Society’s restaging a daring, even courageous, move is the physical and conceptual scale of the import of a recent and well-received exhibition held at the conspicuous non-site of the Venice Biennale. Extending the life of the pavilion as a whole rather than just the works themselves exacerbates the idea of biennials and art fairs as sites of exchange rather than one of production.

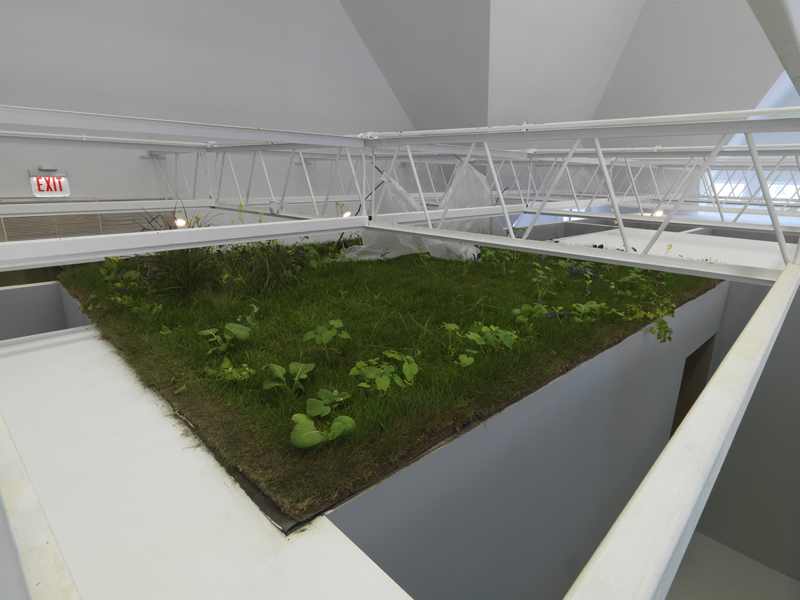

The Romanian pavilion, an enclosed structure, appears rather like a box “plopped” inside the Renaissance Society’s gallery space. Resembling a white-walled shipping container, it could have been prefabricated for overseas transport from its initial inception, even before its landing in Chicago. In fact, the structure was designed by studioBASAR, an architecture studio that designs interventions in the built environment, and as such this portable stage set-cum-architectural model emphasizes a set of physical imperatives to viewing the works in the exhibition. Upon entrance to the gallery, the only external markers on the pavilion are a cut-out doorway and a grassy plot sodden to the roof somehow kept wondrously fertile and fragrant while indoors.

Once inside the pavilion, the first room is empty, an existential waiting room, signaling the first interval in the exhibition. Peeking around the corner reveals Stefan Constantinescu’s short film Troleibuzul 92 [Trolley Bus 92] in a room aptly outfitted with bus seats, the blue plastic frames of which will look familiar to any traveler on the Chicago transit system. This might be one of the few local touches in the exhibition. From the empty yet well-lit room of the first corridor to the dark station of the next, the first words I heard during the film loop were terrifying: a man, utilizing a common mistake of public transportation etiquette, takes out his cell phone on a crowded bus and loudly harangues a woman–wife or lover–on the other end of the call, threatening to murder her in visceral detail.

Implicated in this scene of potential violence, you, the viewer, become a stand-in for the elderly woman and the rest of the passengers who remain calm throughout the protagonist’s tirades. And although I have never confronted a similarly violent situation while taking the train, how many times have I sat by in a public space unaware of how to react or deadened by acts of wayward patriarchy–cat calls, unprovoked glances, and the like; we tolerate what becomes familiar in our own localities. After the initial shock of the protagonist’s violent outpourings, his drama begins to resemble a manic episode. He becomes quiet, almost in tears, after hearing what can be assumed to be soothing or placating words on the other end of the line. However, the unknown female’s role as pacifier can only temporarily soothe this bloodthirsty yet wholly contemporary barbarian, and as such, he takes out his phone, calls her again, and the cycle persists.

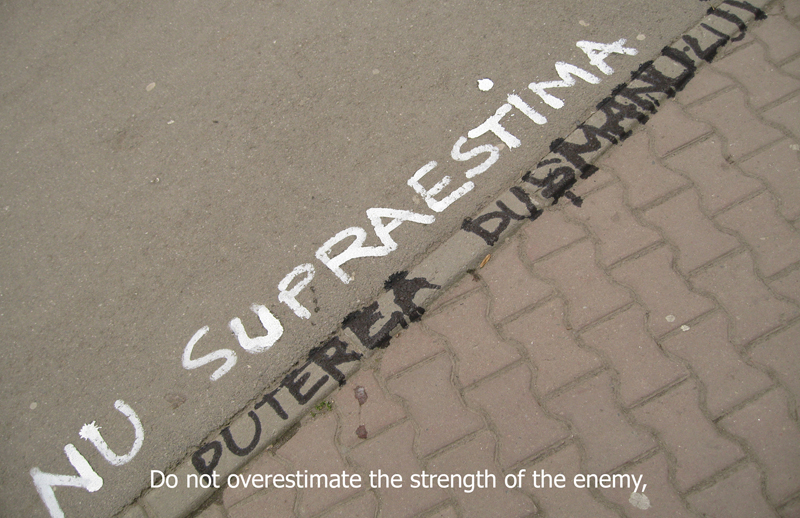

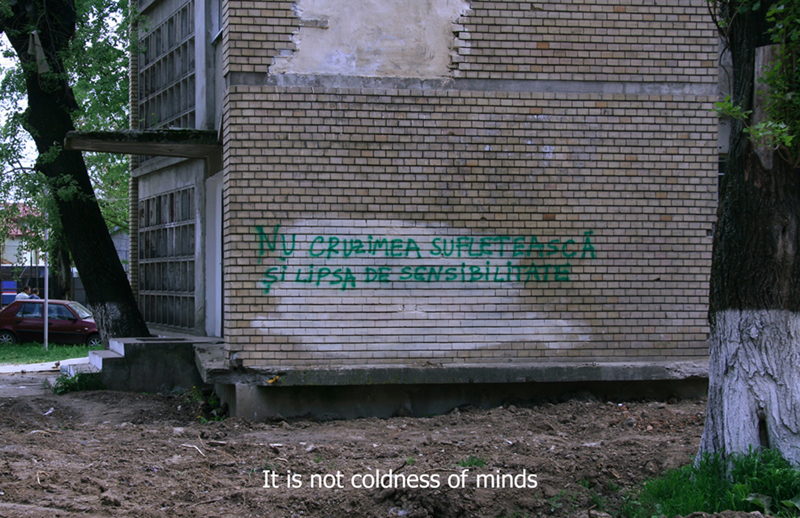

From this scene of intimacy gone awry on public transportation, one is lead through corridors to the next room with Ciprian Muresan’s Auto-da-Fé (2008). The work consists of three slide projectors and 154 slides that flicker for a few seconds each, shows photographs of politicized graffiti from a pre-Democratic Romania, including exaltations such as: “Do not overestimate the strength of the enemy,” and “money, money, and yet more money.” Although at times graffiti is able to provoke a citizenry into action, sometimes it seems just as much like a teenager’s lament to a disinterested parent–exclamations that, without an attuned audience, dissolve into the wind. The work’s combination of obsolete technology with a cryptic call to arms produces another interpretation of the interval, as a space of rupture between a now-historic past and its present day interpretation.

The next room alternates yet again between darkness and light, with part of Andrea Faciu’s EXUBERANTIA suspended (2009) dripping its contents from a suspended water hose into a wooden barrel. Benches placed around the barrel remind us of the stale absurdity of waiting–and for what, for the length of time it takes water to fill a bucket? This conceptualization of time as the organization of actions, however simple and unnecessary, would remain dryly pessimistic if it were not for the audio component of this exhibition, a looped recording of polyphonic voices repeating variations upon the lines, “Pieces of you are pieces of me/I still remember which they could be.” Although the source of these lines remains obscure, they seem poignantly familiar through their simple requiem for love lost commingled with a simple “me/be” rhyme, two elements familiar to any pop song. These words strike the spectator like a hit song from a decade past whose title escapes you even though you can still remember exactly where you were when you first heard the lines.

When you enter the next room after this episode of pop lyricism, Muresan’s second work in the exhibition you are soon enveloped by the dark and malicious corners of the mind. Dog Luv (2009) is a haunting play that consists of a scraggly, canine troupe of marionettes. The script, adapted from a screenplay by the talented writer and playwright Saviana Stanescu (who has lived in New York City since 2001 and now teaches Drama at NYU), begins with an adaptation of sorts–a contemporaneous addendum to Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish–whereby the puppets recite a short history of human torture, a list that includes a variety of incidents: the Salem witch trials, the guillotine, and most recently, the psychological and sexual torture committed at Abu Gharib.

Stanescu’s simple trick of substituting animas for human actors helps elucidate that inhumane actions such as torture are familiar only to the human species. Muresan’s staging of Dog Luv points to humanity as the wellspring of the inhumane by allowing the marionettes’ puppeteers to emerge on film so that we know that it is humans who are behind the movements and voices of these depraved puppets.

Stanescu’s simple trick of substituting animas for human actors helps elucidate that inhumane actions such as torture are familiar only to the human species. Muresan’s staging of Dog Luv points to humanity as the wellspring of the inhumane by allowing the marionettes’ puppeteers to emerge on film so that we know that it is humans who are behind the movements and voices of these depraved puppets.

After this film, more wandering ensues, and in keeping with the motif of the interval, how better to wander and stray than to keep to a known path. Passengen (2005), another film by Constantinescu, has been installed in a room filled with antiquated wooden movie theater seats. Although this film was described by Renaissance Society Curator Hamza Walker as a “first person account of a small group of Chilean political refugees,” it is also filled with lighthearted moments and up-tempo music–an uplifting gesture, however slight, after encountering Stanescu and Muresan’s plumbing of the most unspeakable aspects of the human psyche, and one that brings full circle Jean-Luc Nancy’s description of the interval as necessarily lyrical. The interval as a new note produced from discord is inherently hopeful, even while it retains traces of a troubled past.

After this film, more wandering ensues, and in keeping with the motif of the interval, how better to wander and stray than to keep to a known path. Passengen (2005), another film by Constantinescu, has been installed in a room filled with antiquated wooden movie theater seats. Although this film was described by Renaissance Society Curator Hamza Walker as a “first person account of a small group of Chilean political refugees,” it is also filled with lighthearted moments and up-tempo music–an uplifting gesture, however slight, after encountering Stanescu and Muresan’s plumbing of the most unspeakable aspects of the human psyche, and one that brings full circle Jean-Luc Nancy’s description of the interval as necessarily lyrical. The interval as a new note produced from discord is inherently hopeful, even while it retains traces of a troubled past.

Nowhere is this hope more prevalent than in the final room of the labyrinthine pavilion, found by following a shallow stairwell to the left of the pavilion’s exit. Taking the stairs reveals the second part of EXUBERANTIA suspended, a spry patch of green meadow growing atopthe pavilion that discloses itself as the source of the water dripping into the barrel held in the pavilion below. Although a calming reminder of what hope exists above, while the pavilion below contains human drama and horror, this Romantic vista downplays itself through its scale–only a patch of grass, as if this were all of Nature that could be “saved.” Traces of human life are anything but heroic in this setting, where two makeshift plastic tents have been assembled, but only haphazardly and without any real protection from the elements. These basic architectural dwellings hint at failure amidst a gorgeous yet disheveled wilderness scene. From the top of the pavilion, on a temperate summer day, it is possible to see past the open windows of the gallery space and onto the university campus. This connects the microcosm of the Biennial with the exhibition’s specific location as the ivy growing along the sides of the academic buildings begins to converge with the flora and fauna atop the Romanian pavilion. This reveals how the interval, however liminal, is never so distant as to be obscure. Its seductiveness lies in the constant traffic of visual connections across geographic and historical modalities.