Regional Resonances: In Search of the Transnational in Central East European Art of the 1970s

East European art scenes have long invited mostly negative comparisons with their West European counterparts. During the Cold War era, external perceptions often blurred the many differences between state socialisms and their related cultural fields. For their part, local artists and art historians in the countries of Eastern Europe criticized such homogenizing accounts, pointing instead to the many, and wide-ranging, Western connections of individual artists or artist groups with the West, as well as their distance from so-called official art. Another question was also rarely asked: whether there was any dialogue between artists working in different state-socialist societies of Eastern Europe, beyond the official ties between their so-called “friendly” socialist countries.

Published jointly by ARTMargins Online and ARTMargins Print Journal, this special issue asks why inter- and intra-regional connections and the international networking ambitions of neo-avant-garde artists from the countries of Eastern Europe have been marginalized. Why do historical accounts and recollections continue to ignore the possibility of formative exchanges between the different art scenes in this region? The project’s origins lie in the results of a multi-tiered research project entitled Resonances: Regional and Transregional Cultural Transfer in the Art of the 1970s. Launched in 2022, the project explores artistic transfers between Eastern European artists, curators, critics, and intellectuals with the goal of creating a transnational and dialogic history of neo-avant-garde art in East-Central Europe.(See the project’s website: http://resonances.artpool.hu/ The project was supported by the International Visegrad Fund, and the following participating institutions: Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest; Department of Art History, Comenius University, Bratislava; Academic Research Centre of the Academy of Fine Arts (VVP AVU), Prague; and the Piotr Piotrowski Center for Research on East-Central Europe at the Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań. In parallel with this Special Issue, the periodical of the Academic Research Centre of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (VVP AVU), Notebook for Art, Theory, and Related Zones dedicated its 35/2023 issue to the project and published six articles developed from papers presented at Resonances conferences.) This ambition has several predecessors. For example, reform movements such as the 1968 Prague Spring, or the introduction of self-management in socialist Yugoslavia after 1968 fueled hopes that Western art scenes could provide inspiration and models for progressive art in the countries of East-Central Europe. Later, the need for regional overviews—with the crucial exception of Piotr Piotrowski’s notion of a “horizontal” art history—was expressed mostly by Western art institutions, which from the 1970s onward became the chief initiators of East European art exhibitions.(The first wave of such projects came in the 1970s with Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa (Du Mont, 1972); the Biennale del Dissenso (Venice, 1977); and Works and Words: International Art Manifestation (De Appel, Amsterdam, 1979). This was followed in the 1990s by Europa, Europa: Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, (Bonn, 1994); Beyond Belief: Contemporary Art from East Central Europe, which traveled to several institutions in the US in 1995-6; and Aspects/Positions: 50 Years of Art in Central Europe 1949-1999 (MUMOK, Vienna, 1999). The most recent example, Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.) At the same time, the increasing globalization of the art world created a sense that there are other cultural scenes experiencing similar processes of post-socialist transition. Whether the community of scholars interested in this phenomenon can be extended to connect post-socialist and postcolonial discourses and decolonial movements was a question that was raised and debated in the 2000s(By among others, David Chioni Moore’s article “Is the Post- in Postcolonial the Post- in Post-Soviet? Toward a Global Postcolonial Critique” PMLA 116, no. 1, (January 2001), pp. 111-128, Ekaterina Dyogot (“How to Qualify for Postcolonial Discourse” ArtMargins Online, November 02, 2001) and Margaret Dikovitskaya’s response to it on ArtMargins Online, January 31, 2002, https://artmargins.com/a-response-to-ekaterina-dyogots-article-does-russia-qualify-for-postcolonial-discourse/.) giving rise to a renewed interest in transregional comparative studies.

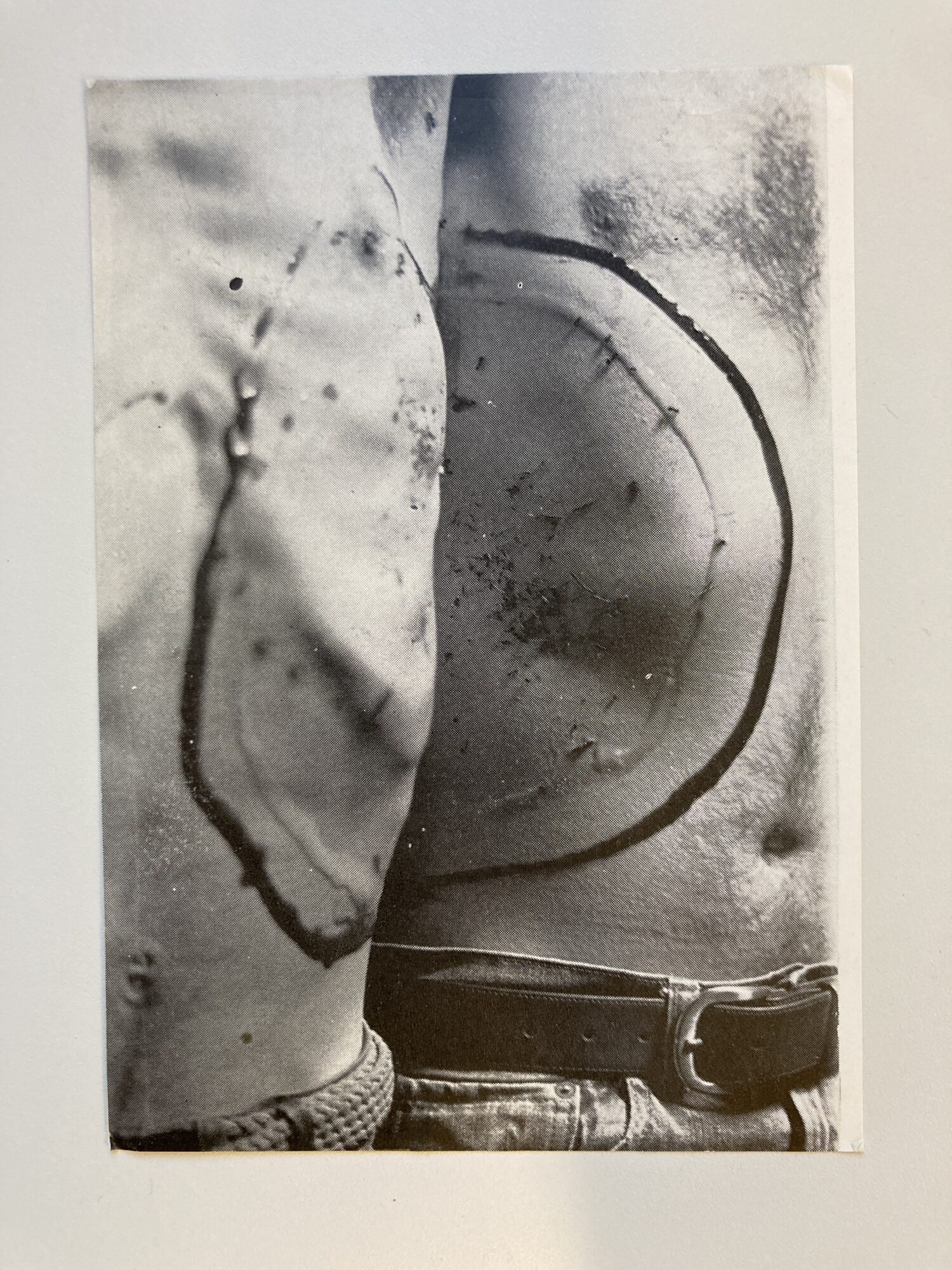

Petr Štembera. Connection (with Tom Marioni), 1975. Photomechanical reproduction on a card. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and KEMKI.

In this context, the notion of cultural transfer—developed to reform comparative historiographies—appeared relevant but was yet to be considered for assessing East European art scenes.(The Hungarian art historian, Katalin Sinkó has already proposed to apply the concept of cultural transfer to travelling exhibitions presenting Central East European Modernisms in “A kiállítás mint kulturális transzfer” (Exhibition as Cultural Transfer) in Nemzeti Képtár. “Emlékezet és történelem között” (National Picture Gallery) Annales de la Galerie Nationale Hongroise, 2008 (Budapest, 2009), pp. 147-63. Several later publications focused on networks, connectivity, and circulation in relation to East European art scenes or more broadly—for instance, Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, and Piotr Piotrowski, eds., Art beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945-1989), Leipzig Studies on the History and Culture of East-Central Europe (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2016) and Klara Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe, 1965-1981 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019)—but mostly without explicitly examining if cross-border interactions generated any meaningful and reciprocal impact on artistic concepts and practices.) Introducing the concept of cultural transfer in the late 1980s, Michel Espagne and Michael Werner initiated research into reciprocal exchanges between cultural spheres. Histoire croisé—advocated by Werner, and Bénédicte Zimmermann in the 2000s—went further, claiming that in most historical processes there are significant aspects that cannot be described within the national frameworks of societies and cultures. The project Resonances endeavored to test the applicability of these theoretical propositions in the field of art history in Central Eastern Europe during the Cold War era, in the hope of uncovering “East-East” intraregional artistic dialogs instead of strategically gathering parallel national narratives.

However, the conversations, negotiations, and colloquia between the members of this transnational research group have significantly recast this initial endeavor and proved that such undertakings are much easier to propose than to systematically pursue. Even if it appears urgent to transcend the frames of national art histories, a researcher encounters several unresolved practical and methodological challenges on this road. When adopting a transnational approach to the study of art events, scholars must be aware of the situatedness of their account and the limits of their specific viewpoint, which cannot be completely collectivized or transnationalized. On the other hand, the desire to define cultural specificity and recreate the lost continuity with local traditions can be tools of a quasi-decolonial delinking—if we interpret the socialist period of these countries as a state of subjugation limiting their cultural-political-economic independence. However, this vernacular approach—even the critique of Western hegemonies—has been readily and frequently instrumentalized by nationalist political rhetoric.

Instead of offering quick solutions to these dilemmas, the articles comprising this special issue accomplish a more modest program by highlighting different, but intersecting aspects or threads of the same intertwined web of transnational relations, friendships, exchanges, art events, and collaborations. The supporting characters in one article become protagonists in another; similarly, they elaborate on events and venues that remain in the background in the other texts. In the online component of the issue—released over the next several weeks—Zsuzsa László’s and Hana Buddeus’s articles inquire into the prerequisites of transnational dialogues. László presents the emerging significance of mediation between different languages, art scenes, audiences, discourses, and artistic idioms, which became an interconnected mission in the curatorial and theoretical activities of the Hungarian art historian, László Beke. This contribution surveys Beke’s transnational curatorial projects from the 1970s, in which cross-border friendships played a seminal role. Similarly, Hana Buddeus writes about the unique mediating role circulating photographs played in transnational artistic dialogs. As Buddeus points out, these traveling photographs—by, among others, Petr Štembera and Jiří Kovanda—not only granted neo-avant-garde artists in socialist countries access to participation in international exhibitions and publications but, due to their material transformation through various printing techniques, they also documented the capricious itineraries of various transnational exchanges.

By the mid-1970s, the quantitative extension of networks and exhibitions organized through postal exchanges were counterbalanced by a qualitative incentive for personal meetings, discussions, and spending time together with fellow artists from other countries. Małgorzata Miśniakewicz’s article takes the 1975 Gdańsk F-Art Festival as a case study and demonstrates how this sociable inclination and dialogicity was reflected in the organization of the festival and in the contributions by Ewa Partum, Niels Lomholt, Endre Tót, Goran Trbuljak, and Anna Kutera. Alina Șerban reconstructs how trips to East Germany as well as contacts and collaborations with East German artists—most notably Robert Rehfeldt—from the late 1960s to the early 1980s shaped the oeuvre of Constantin Flondor, an experimental artist based in Timișoara. Her article foregrounds the role transnational friendships played in the practice of artists who had to maneuver between state-governed institutions that provided funding, mobility, infrastructure, and actions realized in small, private circles that allowed them to playfully debunk the stern rhetoric of the state-defined art field. While each article presents a specific approach to the study of transnational dialogues and cultural transfers, this issue as a whole offers polyphonic, intersecting narratives of the art of the region in an era whose unprocessed legacy still has a critical effect on our present struggles for globally relevant, autonomous, and progressive art scenes.

Further articles of this Special Issue are upcoming this year in ARTMargins Print. You can read other articles from this Special Issue published on ARTMargins Online below: