Ilya Kabakov and the Concentrated Spectacle of Soviet Power

Painting, that is, the idea of painting, dominated Ilya Kabakov’s formative years as an artist in the Soviet Union. These were the late 1950s and early 1960s, the years of de-Stalinization and Nikita Khrushchev’s faltering reform of the Soviet state.

Remembering those years, Kabakov recalls, “One must say that the fetishization of the word ‘painting’ at the time was very great. It was endlessly discussed, what is genuine painting? What is not genuine? What is its relationship to nature, to the truth of life?”(Ilya Kabakov, 60-e — 70-e…zapiski o neofitsial’noi zhizni v Moskve (Vienna: Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, Sonderband 47, 1999), 11.) Accordingly, Kabakov responded to these fetishized questions with a work of his own.

From 1957 to 1961, in a series of cramped apartments and far-flung, grimy “studios,” under the negligible illumination of basement windows, in the spare moments retrieved after his “official” labor as a children’s book illustrator had been accomplished, Kabakov worked doggedly on what he called “his masterpiece.”

A large work of pastels and variable gray tones, the canvas strove, in Kabakov’s words, to unify the “truth of life” with the “painterliness” of the Russian avant-garde. Kabakov describes the piece as follows:

“On it was depicted a deserted area on the outskirts of a city. In the background are some houses and narrow streets, the last rays of sunlight are disappearing, but the sky is still bright. There is an old, blue circus wagon—the door is open and a clown sits inside.

In front of the wagon there is a small performance-a clown in a white costume waves his arms, a little ballerina in pink tights raises her leg, an acrobat in stripes stands on his hands. Around them are spectators: on the left, a few old women sitting and standing; on the right is a peasant group: a man with a wide brimmed hat leaning against a donkey, and next to him someone else, perhaps a woman.”

Kabakov continues, “Everything is orchestrated with profundity and metaphysics and filled with meaning (the old women are not old women, but old age itself; the clown is not a clown, but the embodiment of self-humiliation; this is not a ballerina, but the ‘eternal feminine,’ etc.).

Pablo Picasso. Family of Saltimbanques. 1905.

Robert Falk. The Black Musician. 1917.

And here is the most important idea: that deep thoughtfulness and tremendous meaning were embedded in the very flesh of the picture [plot’ kartiny].”(Ibid.) From this description, and this is now apparently all that remains of the work, the paintings of Pablo Picasso’s Rose period, as well as the painterly, melancholic canvases of Robert Falk appear to have informed Kabakov’s conception of the piece.(An important retrospective of Picasso’s work took place in Moscow in 1956. During his years as a student at the Surikov Institute in Moscow, Kabakov had become acquainted with Robert Falk, one of the last remaining representatives of the Russian avant-garde.)

However, more generally, the “masterpiece” embodied the modernist tropes of marginality, performance, and alienation; this would be a work of pathos, of symbolism, of genius, but most importantly, of art; a creation conceived within the contorted genealogy of modern art pieced together by Kabakov in his Moscow studio; a painting that would secure the artist’s place among the works of Western modernism that had appeared in the Soviet Union at the World Youth Festival in 1957 and the American National Exhibition in 1959.

However, as the artist Erik Bulatov recalls, “Kabakov was passionate about trying to paint this painting and then one day he decided it was shit, and just threw it away.”(Erik Bulatov, “Conversation with Amei Wallach,” in Amei Wallach, Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1996), 33.) And it is here, really, that my questions begin: why does Kabakov’s mature art practice begin with this prolonged, failed encounter with painting and a kind of modernism?

Clearly, something stale and nostalgic permeated this work, as if modernist painting were being travestied, as if Kabakov belatedly realized that his position in Moscow in 1961 existed outside of the modernity to which Picasso and Falk had responded, as if Kabakov grasped that the “being-in-the-world” proposed by his canvas could not yield access to his particular “unhappy consciousness,” but rather would demand of him more and varied forms of false consciousness.

That is, the already inscribed conventions of avant-garde experience, of painting as existential discovery or therapeutic recovery, of paintings as vessels of affect and ideological contestation, that all of those meanings, had been canceled for Kabakov.

In other words, it is the failure of this experiment, of Kabakov’s putative masterpiece, to which I am pointing. Kabakov would later state, “Modernism has to do with an extraordinary confidence on the part of the individual artists in their own genius, a confidence that they are revealing some profound truth and that they are doing it for the first time.”(Robert Storr, “An Interview with Ilya Kabakov,” Art in America (January, 1995), 67.)

Whether this is a fair description of modernism or not, is for the moment, beside the point. This was Kabakov’s modernism, or would-be modernism, and he could not make it work.

Instead, adopting strategies that confronted his historical position in its factual detail and necessity, Kabakov abandoned the primacy of painting and searched out modes of representation that would probe the material conditions of his experience of Soviet modernity.

Ilya Kabakov occupied an ambiguous position in Soviet society: he created “unofficial” art, yet by 1965, he had become a full member of the powerful Union of Soviet Artists. Without the approval of the Union, one had no legal right to be an artist.

Kabakov, however, was a well-employed children’s book illustrator, a government-approved, official artist. Unlike dissident cultural figures, such as the unofficial, “non-Union” painters Oskar Rabin and Anatolii Zverev, or nettlesome quasi-official artists such as the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, Kabakov worked as a Union member for the state publishing houses, annually turning out multiple illustration jobs.

Ilya Kabakov. Cover design for Iurii Iakovlev’s Letter of the Pioneers to the Sun. 1964.

Works such as the cover illustration for 1963’s The Pioneers’ Letter to the Sun earned Kabakov access not only to his salary, but to art supplies, an art studio, domestic vacations, and even the rare trip to Czechoslovakia or East Germany-that is, the sought-after appurtenances of the successful Soviet intellectual laborer.

Moreover, Kabakov did not claim moral authority, nor did he accept the mantle of political dissidence. Even following his subsequent emigration to the West, Kabakov squarely states, “I was not a dissident. I did not fight with anything or anybody. The word does not apply to me.”(Ilya Kabakov, “Interview,” in Soviet Dissident Artists: Interviews After Perestroika, eds. Renee Baigell and Matthew Baigell (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 142.)

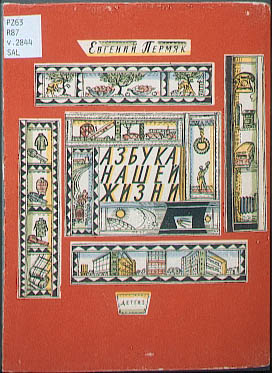

Ilya Kabakov. Cover Design for Evgenii Permiak’s Alphabet of Our Life. 1963.

Rather, Kabakov performed his assigned tasks as the sheepishly efficient artist functionary, as in his bold, vaguely Constructivist cover illustration for Evgenii Permiak’s The Alphabet of Our Life (1963), a kind of ideological primer for Soviet preteens.

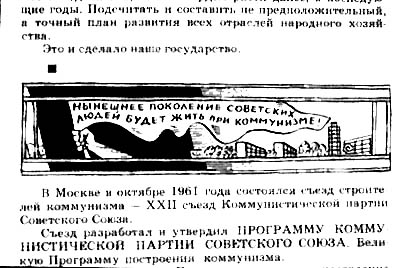

In the margins of Permiak’s text, one encounters Kabakov’s renderings of unemployed proletarians in the West, a crowned plutocrat seated in a stylish chair next to a miniature oil well, and a stridently raised banner bearing Khrushchev’s prediction that, “The Current Generation of the Soviet People Will Live Under Communism.”

Such illustrations make plain the extent to which Kabakov assumed the role of state illustrator in explicitly ideological terms; however, such works were anomalous. More typically, Kabakov’s illustrations featured animals, trains, houses, children, and the paraphernalia of domesticity-images apparently innocent of political import.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from Evgenii Permiak’s Alphabet of Our Life. 1963.

Of course, one could argue that Kabakov’s chorus lines of ponies prancing into shiny locomotives served as fertile metaphorical ground on which to welcome Young Pioneers into the Communist future, but this is not my present argument.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from Evgenii Permiak’s Alphabet of Our Life. 1963.

No, I want to suggest that Kabakov’s manifest talent as a graphic artist, his ability to create whimsical, appealing landscapes of fantasy and freedom, underscores the fundamental contradiction of his position: to succeed was to fail. The more enchanting their visions, the more disarming their immediacy, the more profoundly Kabakov’s illustrations entrapped the producer within the official cultural apparatus.

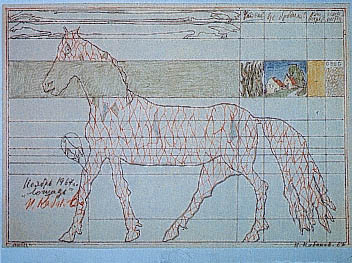

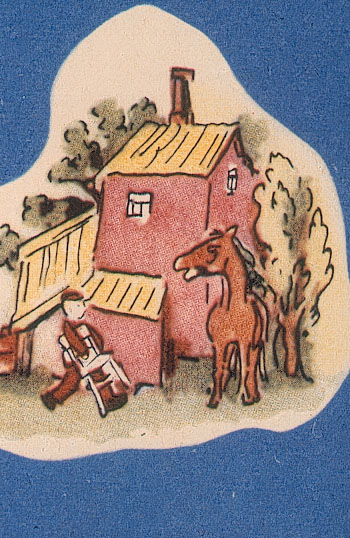

It is in tandem with these “official” illustrations that Kabakov executed a number of “unofficial” pencil-and-ink drawings on paper. Among these works are Horse (1967), which is juxtaposed here with a contemporaneous full-page official illustration of a horse (1964). Similarly, the unofficial drawing Stool, Cat, Belt, Moth, and Fly (1964) suggests comparison with an official illustration of domestic tools and furniture of the same year.

Ilya Kabakov. Horse. 1967.

Completed in the aftermath of the “masterpiece,” Horse and Stool, Cat, Belt, Moth, and Fly were designated by Kabakov as “unofficial,” personal drawings, made “for himself”; yet unlike most “dissident” artists who sometimes illustrated books (among them, the aforementioned Oskar Rabin and Erik Bulatov), Kabakov did not erect a barrier between his private (i.e., “authentic”) and public (i.e., self-consciously “compromised”) productive selves. In these drawings the robust idiom of the professional illustrations obtrusively metamorphoses into the dissected and desiccated reformulations of the drawings.

Ilya Kabakov. Stool, Cat, Belt, Moth, Fly. 1964.

Kabakov does not attempt to obscure his official status,; rather, he openly ponders the vacuity of the professional production that made his circumstances bearable, and even privileged by Soviet standards. In these drawings, Kabakov works over and works through the official illustrations’ innocuous, homespun imagery, compulsively affirming and subverting his own particular imbrication within the state’s tentacular mechanisms.

Kabakov has stated that he worked within cultural bureaucracies both in the Soviet Union and in the West following his emigration in 1988; he abandoned the Union of Soviet Artists and state publishing houses to take up residence in the Western art world of commissioned projects, kunsthalles, and ICAs. As Kabakov has ironically, yet succinctly, put it, “Yes, I am a bureaucrat.”(Ilya Kabakov to Matthew Jackson, 8 February 2001, Berkeley, CA.)

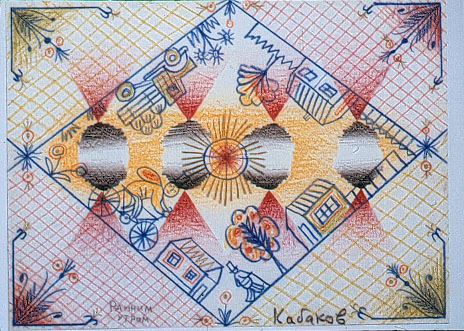

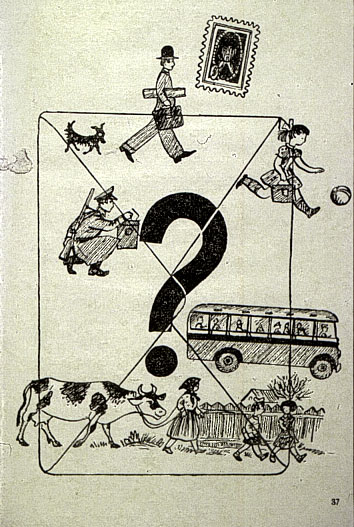

The drawing Ornament (1964) through its dialogue with the language of his illustrations makes vivid Kabakov’s status as an official artist: that is, by repicturing the picket fences, rectangular houses, constantly mobile people, men in hats, embellished plants and trees, speeding vehicles, and overarching geometric design, Kabakov returns to the ingratiating gestures, the precious “ornaments” of his illustrations.

Ilya Kabakov. Ornament. 1964.

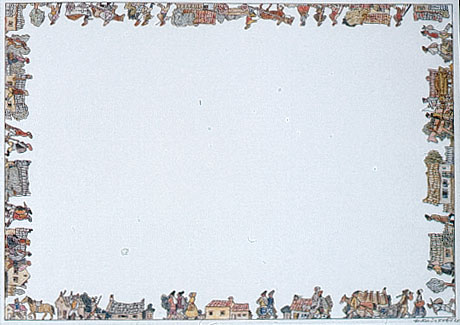

Furthermore, in these drawings Kabakov seizes on the works’ institutional and discursive frameworks, explicitly and even obsessively acknowledging the drawings’ debt to his illustrations. Kabakov makes this framing literal in later drawings such as People, Houses and Horses (1972): the empty center, the teeming periphery, and the insistent presence of the frame itself as portal between work and world define this piece.

Ilya Kabakov. Cover design for To the Children. 1964.

One is led back to the artist-illustrator’s depictions of animals and people on the move, with houses as backdrops, or to Kabakov’s many representations of “people, houses, and horses”; or, the drawing may refer obliquely to typical Soviet posters of the era that featured folkloric, international “Soviet” crowds striving “Toward Communism, In One Rank, Toward One Goal”.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from Letter of the Pioneers to the Sun. 1964.

These images may provide sources for the work’s periphery, but it is the uncompromising structuring emptiness of the abandoned masterpiece, so emphatically materialized in the center, that dominates the drawing.

Through these devices, this work makes manifest the terms of Kabakov’s artistic maturation that followed in the wake of his earlier failure: his art would announce its status as art inasmuch as it renounced its claim to a space of expressive plenitude outside of the bureaucratic, administrative matrix of its making.

To understand Kabakov’s art, then, particularly his drawings, one must come to terms with the function and meaning of bureaucracy in Soviet society. The most ambitious theorization of this subject has been provided by Guy Debord in The Society of the Spectacle (1967) and The Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle (1988).

Debord contends that in all societies of modern production, life has been transformed into an immense accumulation of spectacles, a society of the spectacle, in which human beings no longer communicate directly with each other; where “lived life” itself has disappeared, replaced by a profoundly mediated existence in which all values are established before the subject even arrives on the scene. Debord writes, “in the spectacle all that once was directly lived has become mere representation.”(Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books, 1995), 12.)

Debord goes on to describe two complementary forms of the spectacle, “the diffuse” and “the concentrated,” the former dominant in the West, the latter in the Soviet Union. According to Debord, the West’s diffuse spectacle transforms the individual’s daily activity into the habitual consumption of pseudo-choices in a life-world propelled forward by the rehearsal of already commodified recreations.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from To the Children. 1964.

The Soviet Union’s concentrated spectacle, on the other hand, could offer its subjugated public only one real commodity, the ideology of “Soviet Power.”

Unable to produce objects and their libidinal image networks, the concentrated spectacle could succeed only in mobilizing its police and a corresponding cultural bureaucracy to manipulate and distort perception.(Ibid., 74.) Within Soviet society, Debord writes, “Ideology was no longer a weapon, but an end in itself.”(Ibid., 73.)

Ilya Kabakov. People, Houses and Horses. 1972.Incapable of replicating the West’s phantasmagoria of commodities and commodified experience, the concentrated spectacle proliferated through the imposition of the visual and verbal rhetorics of “Soviet Power,” that is, the self-abnegatory ideology of the bureaucracy’s supposed “proletarian” dictatorship.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from To the Children. 1964.

The mystifications of the concentrated spectacle inscribed themselves daily through a vast, intrusive complex of apparatuses, among them, the intense conditioning of the educational system, in which the young Soviet subject would encounter the potent interpolative cadences of children’s books, and among those voices was certainly Kabakov’s.(Ibid., 74.)

Laying no claim to the moral authority of the dissident artist, Kabakov contends that the interdependence of truth and untruth, of the artistic and inartistic, of the trivial and the tragic, of the official and unofficial, lies at the crux of his art.

Kabakov writes, “When man announces, propounds the truth, all of that leads to deadliness, rigidity, dogmatism, immobility etc. And only untruthfulness allows us to form representations of the real truth, or at least search for it.”(Ilya Kabakov (with Iosif Bakshtein and Andrei Monastyrskii), “Trialog o komnatakh,” in Moskovskii arkhiv novogo iskusstva (Moscow:1987), 94.) Or, as Guy Debord comments, paraphrasing Hegel, “In a world that really has been turned on its head, truth is a moment of falsehood.”(Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 14.)

Kabakov could not represent the concentrated spectacle, give it a recognizable and suitably despicable form, because the spectacle existed everywhere and nowhere, to nail it down in the depiction of one transparent scrap of ideological imagery, would have been to misconstrue and tame it; nor could Kabakov “represent” with self-possession from his disagreeable position within the spectacle, as he had attempted to do with the masterpiece; instead, Kabakov could only enact the decrepitude of the spectacle’s mediations, his mediations, again and again.

Soviet Poster. Circa 1964.

Kabakov never sought an “individualist, ahistorical, asocial expression of authenticity,”(Boris Groys, “The Movable Cave, or Kabakov’s Self-Memorials,” in Ilya Kabakov, eds., Boris Groys, David Ross, and Iwona Blazwick (London: Phaidon, 1998), 34.) rather, he elaborated an antiexpressive parasitism that subverted notions of originality and productive, state-sponsored labor.

The visuality invoked by the artist suggests the recycled, the repetitive, and, quite often, the boring, and through this process, Kabakov became a kind of Soviet tuneiadets, a parasite.

Ilya Kabakov. Illustration from Vladimir Lifshits’ The Rising Road. 1964.

Applied by Soviet officialdom to intellectuals who refused to serve the state and also to those who merely attempted to practice art outside the confines of state control, the image of the tuneiadets iconically embodied the shiftless, self-absorbed intellectual: the tuneiadets was a slacker, a sponger, a layabout, a parasite on the body politic of Soviet society (the poet Iosif Brodskii was arrested in 1964 as a tuneiadets).

Kabakov paradoxically realizes this metaphorical language by continually offering up recapitulations of his own production, parasitically feeding upon the detritus of the institutions and administrative imagery of Soviet life, continually reanimating his own official illustrations. Thus, in his art, if not in his life, Kabakov’s allegiance is with the tuneiadets, with the parasite who refuses to work.

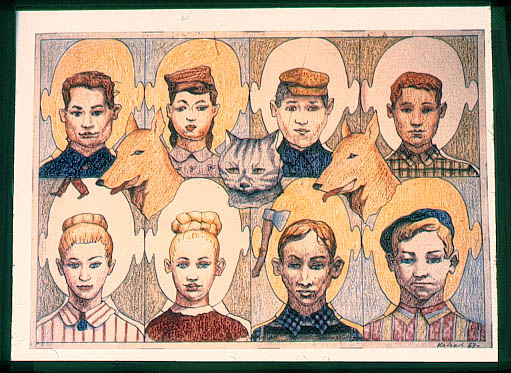

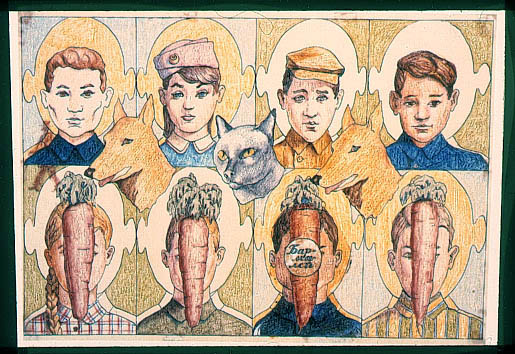

In Kabakov’s official illustrations, depictions of children’s disembodied heads and cuddly, diminutive creatures were ubiquitous and it is this same subject matter that returns in the unofficial drawings entitled Heads (1968).

These playful and disturbing drawings seem to embody Georg Lukács’s description of a modern bureaucracy in which “objectively all issues are subjected to increasingly formal and standardized treatment” indicating “an ever-increasing remoteness from the qualitative and material essence of things.”(Georg Lukacs, History and Class Consciousness, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1971), 99.)

A palpable remoteness from signification and meaning inheres in the synthetic visual repertoire of Heads, even as the drawings brazenly mobilize and defamiliarize the imagery of Kabakov’s illustrations.

Ilya Kabakov. Heads. 1968.

The raggedly colored-in heads of animals and children, the ominous and ridiculous floating objects, and the redundant feet of the walking man on the left do not present representations of real animals, of real children, or of real objects, but rather re-presentations of the illustrator’s rote, professional depictions of such things.

Ilya Kabakov. Heads. 1968.

Most important, these pieces emphatically confound the overflowing metaphoricity invoked by Kabakov in his description of the “masterpiece.” These are not imposing canvases of inspired, painterly genius, of Kabakovian modernism, but rather flimsy sheets of paper etched with the anguished and labored entries of the despairing professional illustrator.

In the end, Kabakov’s unofficial work can be viewed as a species of auto-detournement, or self-appropriation, by Kabakov of his official position and production. Debord introduced the theory of detournment as a means of conceptualizing a counterimagery to the spectacle’s regimes of representation. Debord describes detournment as “the fluid language of anti-ideology.

It occurs within a type of communication aware of its inability to enshrine any inherent and definitive certainty.”(Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 146.) By prodding, prying, mimicking, and reconfiguring the concentrated spectacle’s mediations, Kabakov conjures a kind of lying truthfulness, an anti-ideology deep within ideology, though his work never tires of reiterating that one cannot oppose the spectacle-one can only make its presence absurdly palpable, or palpably absurd.

Or, as Guy Debord writes, “One must lead all forms of pseudocommunication to their utter destruction, to arrive one day at real and direct communication. . . . Victory will be for those who will be able to create disorder without loving it.”(Guy Debord, “Theses on Cultural Revolution,” trans. John Shepley, October (Fall, 1997), 92.)