Forms of Involvement: The Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union and Its 1964 Congress

During the past decade, contemporary artists in Central and Eastern Europe have renewed their interest in Artists’ Unions, and have begun to self-organize.(This article is based on a study by Johana Lomová and Karel Šima, “Sjezd Svazu československých výtvarných umělců v roce 1964. Poznámky k úspěšnosti performance,” (The Conference of the SČSVU in 1964. Notes on the Success of One Performance) in Umění a revoluce (Art and Revolution), ed. Johana Lomová and Jindřich Vybíral (Praha: UMPRUM 2017), 512–545.) After years of what scholar Piotr Piotrowski termed “anti-communism,”(Piotr Piotrowski, Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe (London: Reaktion, 2012), 172.) some aspects of collectivity are becoming appealing again, and the organizational structures and mechanisms used by unions are being reinvented. In Poland, for example, as part of Art Strike in 2012, several cultural institutions closed their doors to call for better working conditions for artists.(On Art Strike, see: http://politicalcritique.org/cee/poland/2017/poland-art-unions/.) In the Czech Republic, an occupation of the exhibition hall Mánes—formerly a residence of the Czechoslovakian (later Czech) Artists’ Union—took place in 2013.(See https://www.facebook.com/Manesumelcum/.) Whereas the Art Strike organizers wanted to make the public aware of the poor and precarious social conditions of artists, the Occupation called for the expropriation of the exhibition hall and for the “democratization” of the Czech Visual Art Foundation to which Mánes and other uinion-owned estates belonged prior to 1989. In this context, this “democratization” referred to discussions that took place within the former East during the 1960s, when a wish to participate in decision-making and the right to choose one’s own governing legislation was not only a question of the political system, but also penetrated the whole society.

This article offers a short history of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union (SČSVU) and reflects on the process of “democratization” that took place at its 1964 Congress. The Union’s complex structure and purpose during the 1960s serves as a setting for a description of different strategies that were used by the Congress delegates in order to participate in decision-making. Two aspects of the Union will be revealed: the pragmatic one and the ideological one. It remains an open question which one is more appealing for our contemporary situation, as the former resulted in the diminution of the Union’s political power and the latter was based on the ideals of Socialist Realism.

The SČSVU was founded in 1947—one year before the Communist Party seized power in Czechoslovakia—as a professional union intended to represent artists’ interests and allow them to negotiate these interests within the framework of the state. It dissolved in 1970. Throughout its twenty-three years of existence, the Union’s role and character changed continuously. After the communist takeover, the state co-opted the originally independent Union and transformed it into an institution to manage artists’ employment and administer their social security and health. It also served as a tool for promoting the cultural policy that was formally defined by the doctrine of Socialist Realism. The aesthetics of Socialist Realism were strictly enforced in the beginning of the 1950s, but their description became less rigid over time, and by the 1960s the style had no precise definition whatsoever. Nonetheless, an official preference for conventional realistic representation (so-called “modernist realism”) persisted.(Alexandra Kusá, Sorela (Bratislava: SNG 2019.) Given the stipulation by Czechoslovak law requiring every adult to be employed with an institution, the Union—in effect—provided its members with the privilege of freelancing. As in other state institutions, the Communist Party organization played a prominent role in all decision-making within the Union. Following an initially inclusive approach that allowed all professional artists to be Union members, the organization adopted an exclusive policy after 1952, conforming to the political requirements of the new regime. It became supportive only of those artists who were willing to put their art in the “service of building socialism,” to participate in regular “actions” and commissions, and to adapt their style to the key demands of Socialist Realism. In other words: to serve society and be understandable to the general public. The year 1956 marked the beginning of the Thaw in Czechoslovakia, and the Union loosened its restrictions on artistic production and organization. Relatively independent art groups—or “creative groups”—were allowed to exist within the SČSVU. Whereas organization of the SČSVU was delineated by regions, the few existing creative groups gathered artists according to their artistic beliefs or style. However, it is not until December 1964 that a radical change in the Union’s policies and approach can be identified: the presidium in charge of the Union, which had formerly advocated an exclusive approach, was replaced by less-restrictive representation composed mainly of members or supporters of the creative groups, which were gathered in the so-called Block of Creative Groups.

The governance structure of the SČSVU consisted of a Central Committee elected by the Union’s Congress; this committee then selected the presidium and the chairman in a separate vote. The election of the 1964 Central Committee is generally regarded as the start of the “democratization” of the organization, marking a moment in a broader shift in Czechoslovakian culture. During the Congress, the tension between those wanting to represent all professional artists (notwithstanding the fidelity of their work to the formulae prescribed by official ideology) and the desire to be an exclusive organization that would organize only artists closely following the officially prescribed demands on art (i.e. those working on state commissions) became evident. The struggle over the nature of the Union was, in a way, a struggle between two approaches to the role of the Union under socialism: one side desired a pragmatic role for the organization, understood as potentially bringing economic benefits to all, while the other side sought an ideological role, emphasizing that only ideological purity in art deserved to be represented by the Union. This ideological approach went hand in hand with the exclusion of all creative production other than fine art, for example, applied art or art theory.

The SČSVU’s complex history is a fascinating one. It is a mixture of politically motivated pressures, personal persuasions (as well as ambitions), and the mundane problems facing artists in the Czechoslovak party-state. Even though the history of the SČSVU is often associated solely with authors working according to the doctrines of socialism, this is not correct; by the 1960s, most Czechoslovakian professional artists (meaning those who had studied and practiced fine art, applied art, or worked as theorists) were members who profited from the Union and took at least a passive role in its decision-making. Its membership was vast: in 1969, the SČSVU had almost 3,700 members, and during the 1960s it supported such diverse personalities as Josef Malejovský, creator of public monuments; Milan Knížák, the subversive Fluxus artist; and Jindřich Chalupecký, art critic and curator of Marcel Duchamp´s exhibition in Prague in 1969.(There were three types of membership: a proper member, a candidate for membership, and a person registered in the Union or its affiliated Fund of Czechoslovakian Artists.)

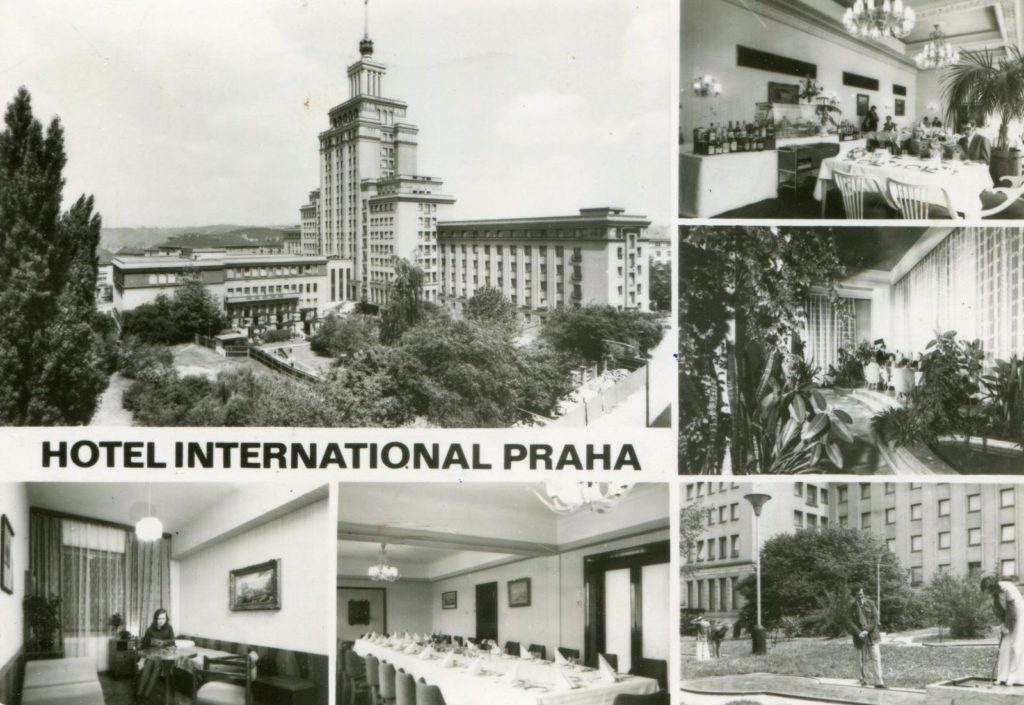

Postcard showing the Hotel International in Prague where the 1964 Congress of the SČSVU took place. Archive of the author.

The 1964 Congress was anticipated with mixed expectations. On one hand, the Communist Party organization—together with the presidium elected in 1960, who were in charge of the preparations of the Congress—were afraid of possible dissent because of a general dissatisfaction in Czechoslovakia with the economic situation caused by the contemporary economic crisis, which began in 1962. Frustration on the part of Czechoslovak artists may be seen in dozens of articles published in Výtvarná práce (The Art Work), the SČSVU´s official journal, wherein members of the Union blamed the organization and its presidium for problems such as the lack of art supplies in shops or problems with the forthcoming tax reform. The atmosphere preceding the Congress was tense, and members of SČSVU´s presidium were in a defensive position as they were associated with the economic situation, whereas their critics had a strong foundation for demanding reform.

One of the reactions to the ongoing critique of the SČSVU was the way the Congress was reported in Výtvarná práce. For the first time in SČSVU history, the results of the Congress’ election and a number of speeches were reprinted in full length in the publication shortly after the event.(Výtvarná práce 12: 22–26 (1968).) However interesting these texts may be, however, they do not provide a full picture of the atmosphere at the Congress, as most of the published material was approved in advance. Luckily, a detailed transcript of all the speeches and polemics that took place during the Congress has been preserved in the National Archives of the Czech Republic.(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, National Archives of the Czech Republic.) Thanks to this document, those speeches not publicized in Výtvarná práce are available, as are records of how the delegates responded, when and how they applauded, and what kinds of information caused whispers among the attending crowd. Although the purpose of the transcript is unclear, this type of information conveys the spirit of the Congress, and demonstrates the struggle for power between the members of the presidium in power since 1960, and those who were to be elected in 1964—or, in other words, between those who were losing their hegemonic position, and those who were gaining such a position.

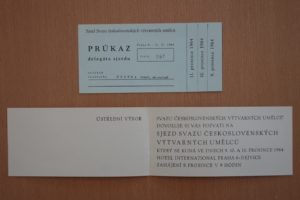

Invitation to the 1964 Congress of SČSVU. Archive of the author.

Within the discussions that were recorded in the transcript, there are four elements that are key for understanding the ideological and discursive shifts taking place within the Union. The first is the intensity of the tension between the outgoing presidium and the delegates. Second is the active yet unorganized participation of the delegates in decision-making. The third are the specific arguments used by the young generation of artists, a group of whom are described in the literature as “winners” of the 1964 Congress, and lastly, there are the organizational issues raised by procedures followed during the SČSVU Congress.

A prime example of the disagreement and discord between the presidium and the delegates is the response to a piece of seemingly unimportant information about a birthday letter and gift sent in the name of the Congress to Antonín Novotný, then President of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Painter Bohumír Dvorský, member of the presidium and one of the Congress chairmen, read aloud a birthday wish that had already been sent to the President. Adolf Hoffmeister, one of the leaders of the opposition and the forthcoming chairman of SČSVU, asked: “Why did you not inform us in advance?” The archival material states that whereas the letter itself received only a mild applause, Hoffmeister’s complaint received “plaudits,”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 10/1.) indicating that the delegates were eager to find opportunities to openly criticize the presidium. In the discussion that followed, no one questioned the formal birthday wish; rather, at issue was the fact that the presidium had sent the letter before the Congress was informed, thus ignoring the rules of procedure and not giving a voice to the delegates. This procedure would not have been problematic in the past, but during the 1964 Congress delegates were given an opportunity to express individual opinions and criticize the bureaucratic machinery of both the Congress and the Union at large.

The delegates’ palpable dissatisfaction regarding the presidium’s exclusive, closed-door decision-making practices also manifested in relation to more significant issues than the dispatch of birthday wishes. Such was the case of a certain (today unknown) painter named Ms. Ryšavá.(She may have been the painter Jožka Ryšavá-Kačírková (1911–1971), but there is not sufficient evidence.) She was expelled from the SČSVU for some sort of economic fraud and appealed to the Congress in the hope that her membership would be renewed. A chaotic discussion ensued, in which delegates accused the chairman of unprofessional work, as the presidium had not provided the Congress with enough information about Ms. Ryšavá´s case in advance. When the chairman decided to establish a special commission that would resolve Ms. Ryšavá´s membership, the delegates protested vehemently asking for their right to directly decide the case themselves, shouting “We want to vote!”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 9/1.) In the ensuing discussion, the quality of Ms. Ryšavá´s paintings was raised and the delegates used the opportunity to articulate their independent aesthetic positions. Applause followed someone’s outcry about Ryšavá’s painting, declaring, “It’s awful.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 10/1.) Graphic designer and abstract painter Jan Kotík asserted, “I wouldn’t be able to say anything nice about her work. Even the frames are ugly.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 32/2.) Similarly to the trifling event with the letter to President Novotný, the case of Ms. Ryšavá was not important for the delegates per se. Judging by the discussion, it appears that it was not a question of her gender or her political view, but rather that her paintings were conservative and other artists did not respect her work. The reason that her case became significant was that it enabled the delegates to exercise their legitimate—yet typically denied—decision-making power. In turn, this empowered them to demand the right to make further, more substantial decisions.

Letter regarding the absence of Stefan Bednár at the 1964 Congress of SČSVU. Archive of the author.

Whereas these two cases illustrate the general atmosphere of the Congress and the opinions shared by the majority of delegates, a speech given by sculptor Vladimír Preclík in the name of young artists and the Block of Creative Groups expressed the revolutionary mood of the younger generation. They felt unrepresented in the SČSVU: they were “mad”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 19/2.) about the structure of the Union, and did not hesitate to express it. According to Preclík, the SČSVU had functioned as a “jackstraw, the owner of the stamps, who decided on our quality, on our possibilities, on our mistakes. There was an omnipresent anonymous person who made decisions, erased, [and] rejected.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 19/2.) Following this expressive condemnation of the Union—castigating it as an entrenched bureaucratic organ—Preclík described the interconnection between the economic situation and the art scene: “By coincidence, our Congress is happening in the time when some outdated forms of our economy are being put on a new basis. We believe that our artistic life also needs a transformation, that we need new practices of artistic life.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 20/5.)

The ambitions of the young artists were high. Preclík’s speech shows how much they despised the authoritative presidium. He did not hesitate to question their personal integrity or express the delegates’ dissatisfaction. The Block of Creative Groups possessed their own list of candidates for the Central Commitee, which was believed to have behaved in a more democratic and open-minded manner. In the end, the 1964 SČSVU Congress did elect a number of these individuals.(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 6/1-6/2.) These candidates fulfilled the ideal personal character described by modernist painter Miloslav Holý following Preclík’s speech: “Thus we have to compose the new Presidium out of people with strong character, who are extremely brave and devoted to art.…We [have] had more than enough of authoritative leadership.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 26/1.)

In the cases of the birthday letter to the president and the membership of Ms. Ryšavá, delegates acted “democratically,” but now they asked for more concrete changes. They demanded that the Central Committee open membership to those who stood for different opinions and were not approved by the Communist Party in advance. These included people active in the Union since the first years of its existence, such as Jindřich Chalupecký and Adolf Hoffmeister; for those who were persecuted in the 1950s, such as surrealist painter Mikuláš Medek; for those who completed their university education after 1948 and started a real career in the second half of the 1950s, such as textile designer Olga Karlíková; and for artists working on state commissions, among them Karel Svolinský.

The reason for the success of the reformist opposition was partly due to the fact that a more participatory voting procedure was introduced during the 1964 Congress. The first change allowed both the Central Committee and the Section Committees to be voted upon using secret ballot. The minutes of the Congress show that this decision was approved without any strong disagreement. The only fear was that delegates wouldn’t be able to complete the ballots correctly, making them invalid.(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 6/1.) That said, one of the most heated discussions during the Congress itself were dedicated to another aspect of the voting procedure. Previously, the Congress had voted in three separate sections (fine artists, applied artists, and theorists), with each electing its own candidates into the Central Committee. The number of candidates was different for each section; according to its membership at the 1964 Congress there were 171 fine artists, 78 applied artists, and 25 theorists. This meant that the strongest section was the fine artists, making them the most powerful voting body in the presidium.

The division into discrete sections seems to have been problematic, as these distinctions did not accurately reflect the practice of artists: a number of those affiliated with the applied art section were also fine artists although they did not identify it as their official profession. Many of the artists, including Jan Kotík and Olga Karlíková, are today perceived as protagonists of nonconformist fine art. The transcripts of the Congress discussions reveal that the delegates were most concerned with this division of voting sections, with numerous speeches on the topic frequently interrupted by spontaneous applause. Kotík, for example, expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that painters did not know many applied artists, and vice versa. Kotík believed that only those SČSVU members that were well known to everyone should be elected into the Central Committee and the presidium.(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 41/1.) Sculptor Miloslav Chlupáč described the logic behind voting decisions: “We vote for them because of their artistic and aesthetic opinion, and that is something shared by all sections. It is not important whether it is a vase or a sculpture. Everything is art … and we want applied art to work toward the same goals as fine art.”(Fond of the Czechoslovakian Artists’ Union, carton 219, 41/3.) Delegates accepted these arguments and, as a result, the Congress decided to open the voting system for the Central Committee and Section Committees so that all Union members voted on the leadership of both committees. Thus, the bureaucratic division into sections was replaced by an openness and by putting art in first place.

Front page of journal Výtvarná práce from 1968 with texts on future of the SČSVU. Archive of the author.

The transcript of the Congress captures its free-minded atmosphere. The delegates were eager to participate in the decision-making process; they expressed their doubts about the current state of the Union, and wanted their dissatisfaction to be heard. The new and unusual system of voting by secret ballot, as well as voting regardless of the section to which a delegate belonged, helped the opposition succeed in disassembling the established power structures that had dominated the SČSVU since its establishment almost two decades before. As a result, the new presidium opened space for a greater variety of artists and, to a great extent, satisfied the demands of its members that the Union be less dependent on centralized political demands and more open to the input of practicing artists with a variety of professional backgrounds and ideological viewpoints. The next Congress, where the presidium elected in 1964 would have had to defend their agenda, never happened. It was first postponed from 1967 to 1968, and after the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact Troops, it never took place. Prior to this abrupt cancellation, however, discussions about the purpose and structure of the Union had persisted.

In 1968, a series of articles about the future of the Union was published in Výtvarná práce. Art historian Luděk Novák argued against an opinion expressed by some reform-minded authors who thought that the Union had become obsolete in the new political situation during 1968 (known as Prague Spring), and thus should be dissolved. However, this argument did not succeed in overcoming the bureaucratic apparatus, one of the repeated criticisms of the presidium in charge prior to 1964. Novák wrote that such a decision would not serve artists, “rather, it would hurt them because in the system of socialist society the community of artists would lose a possibility to scientifically and authoritatively express opinions about fine art.”(Luděk Novák, “Kolem dokola nové organizace” (All-Around the New Organization), Výtvarná práce 16:3 (1968), 10.) According to Novák and other members, this was the role of the Union in 1968, nothing more, nothing less: a forum that allowed SČSVU members to openly exercise their cultural capital as experts on art. The Union was not understood as a political institution (as it had been in 1964), but rather as an instrument of artistic autonomy.

Front page of journal Výtvarná práce from 1964 dedicated to information about the 1964 Congress. Archive of the author.

In the aftermath of the Prague Spring, the SČSVU was dissolved, and in 1972, the single Czechoslovakian union was replaced by two new ones: the Czech Artists’ Union and the Slovakian Artists’ Union. This reorganization meant that all members had to apply anew, and their membership was strictly regulated. It was at this juncture that most members only registered with the Czech Art/Artists Fund (founded in 1954), which allowed them to be freelancers and to sell their works. What they lost was the possibility to play an active role in discussions and decision-making, as they lost the platform that had allowed them to communicate with the political apparatus.

The “democratization” of the structure within the Union and the behavior of its delegates at the 1964 Congress were irreversible. Whereas the twenty years that preceded the Prague Spring could be understood as a continuous period (e.g. the election of the Union’s founders into the Central Committee in 1964), the so-called “normalization” started a new epoch. After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, the Czech Artists’ Union and its fund were transformed into the Foundation of Czech Art, and then its estate was improperly appropriated by certain members of the foundation for their own personal use. One possible cause for this takeover may have been precisely the interruption in the organization’s continuity: after 1989, there was nothing to return to, and artists active in the Union in the 1960s did not try to revitalize the institution under the new conditions of a democratic state. Likewise, there were (at the time, and for decades after) no lessons learned from the disagreements and contradicting ideas discussed above, about the role Artists’ Union should have had played during the social and political upheaval of the 1960s, and the underlying tensions between that institution’s pragmatic and ideological approaches (however different their arguments may be) are still present, weakening the potential that Artists’ Unions could possess today, and the effect they could have on artists’ potential for collective and participatory action.

Acknowledgments: This study is a result of research funded by the Czech Science Foundation as the project GA ČR 19-24996S, “In the Search of the Meaning of Art: Jindřich Chalupecký (1910–1990)”

Other articles in the issue include: