Dialogue between Yevgeniy Fiks and Thomas Sokolowski about Fiks’ recent show at the Zimmerli Art Museum

Yevgeniy Fiks calls himself a “post-Soviet” artist, thus designating his personal history of belonging to the generation that was born in the Soviet Union and came to the West after its collapse. His work can be characterized as an archival exploration of history, understood as the unearthing of facts, events, and narratives that have been forgotten or obscured by dominant ideological discourses. His first “mini-retrospective” entitled Mr. Deviant, Comrade Degenerate: Selected Works by Yevgeniy Fiks, which was on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University until the end of July, focuses on three different types of nonconformism – artistic, gender, and political – that fueled anger of the establishment both in the Soviet Union and in the United States during the Cold War. The show brought together works that were created in the past twelve years, examining various kinds of dissent against the status quo. The earliest work in the show, Communist Guide to New York City (2007), is a projection featuring photographs of buildings linked to the history of the Communist Party in the United States.

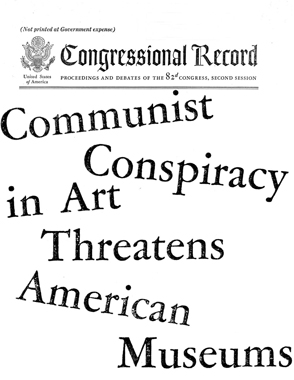

This history is largely invisible to an average person, because the buildings in which it happened are not identified for a public eye by memorial plaques or other markers. A year later, in a multi-media installation entitled simply Moscow (2008), Fiks focused on documenting a parallel invisibility of the life of gay people in the Soviet Moscow, photographing cruising sites popular over the roughly 70 years of Communist rule. By 2010, Fiks turned his attention to Communist-loathing Senator McCarthy’s supporters’ views on modern art. In Communist Conspiracy in Art Threatens American Museums (2009), Fiks examines American conservatives’ understanding of modern art as a Communist conspiracy intended to undermine the stability of the United States, as exemplified by the views of US Congressman George Dondero.

Yevgeniy Fiks, Communist Conspiracy in Art Threatens American Museums, 2009. Multi-media Installation. Image courtesy of Yevgeniy Fiks.

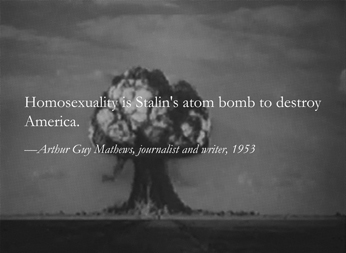

In Stalin’s Directive on Modern Art from the same year, the artist brought to light a theory propagated in the 1950s America that modern art was a Stalinist plot “to create confusion in art and literature, promote the juvenile, the primitive, and the insane, and to further the perverted and the aberrant.” Fiks displayed two works from 2012in the show: a multimedia installation Homosexuality is Stalin’s Bomb to Destroy America and a series of C-prints Joe-1 Cruising in Washington, DC, in which he exposes the conservatives’ belief that homosexuality was a tool with which the Soviet Union was conspiring to destroy the foundations of American society. Lenin’s Tomb (Guy Burgess) from 2014 servesas a possible “proof” of these hair brained conspiracy theories. The work consists of three archival prints featuring a British spy and a Soviet mole, Guy Burgess, who was gay and who defected to the Soviet Union in the 1950s. The installation Homo-Abstractionists (2019), the latest work in the show, zeroes in on Nikita Khrushchev’s rant against modern artists, in which he called them “damned homos,” thereby echoing the comparisons between Communism, homosexuality, Communism, and modern art that were made by the conservatives in the United States.

Interview with Yevgeniy Fiks (New York City)

Natasha Kurchanova: Your personal exhibition, Mister Deviant, Comrade Degenerate: Selected Works by Yevgeniy Fiks just opened at Zimmerli Art Museum. As I understand it, this exhibition is about different types of nonconformism – political, sexual, and artistic – and similarity with which they are treated by leaders of seemingly antagonistic political regimes, those of the Soviet Union and the United States during the time of the cold war.

Yevgeniy Fiks, Stalin’s Atom Bomb a.k.a. Homosexuality, No. 5, 2012. Giclee print. Image courtesy of Yevgeniy Fiks.

Yevgeniy Fiks: The themes of nonconformism viewed from political, sexual and artistic perspectives are not knew for me. I have been working on them for years. In 2008, I organized an exhibition entitled Communist Guide to New York City, in which I explored the theme of political nonconformism in the United States. This subject interested me, because there is a strongly felt taboo against Communism in the United States. Communists are considered anti-American, in a way. When I lived in the Soviet Union, I was fascinated by dissidents, people who opposed the Communist regime. In American Communists I saw American dissidents. In general, I am interested in unknown, hidden, taboo history. I guess, I came to be interested in American Communists because of my interest in history. The project on view at Zimmerli now, the Communist Guide to New York (2007), is a series of photographs that show buildings in which the history of American Communism took place – mostly in the 20thcentury, with a few exceptions from the 19thcentury. Before I began the project on the history of American Communism, I painted a series of portraits of present-day American Communists. This was done around 2005-2007. My exploration of Communist America reflects my interest in otherness, in a belief, ideology or a trait that is impossible to assimilate. Nowadays, Communism appears to be absolutely unacceptable to mainstream Americans, even though in the 19thcentury and before World War II, the Communist movement here was very much alive and well. After the war, this movement was prosecuted and marginalized. At present, the politics is changing and it is not clear what’s going to happen, but during the Cold War, prosecution of Communists was ruthless.

NK: How do you obtain material for your work?

YF: I do research on the topics that interest me. For example, for the Communist Guide to New York, I found information on the internet and in books. There is a great book, Radical Walking Tours of New York City, where one can find information on several radical movements. In this particular project, I focused on Communists. It is not an unknown history, of course. I may have introduced this subject to contemporary art, but it is well-familiar to historians. The places I photographed are also well-known.

NK: You used these photographs as documents of sorts.

YF: Yes, absolutely. I used them as documents. Because the history of Communism is hidden in the city, it is not necessarily visible. The buildings do not have any memorial signs, identifying them as historical sites. The photographs of them in the exhibition are also kind of mute. They do not symbolize Communism. On the contrary, they look like ordinary New York buildings. However, they do have a history that is not indicated by visual markers.

NK: And in this case, this resembles the history of gays.

Yevgeniy Fiks, Moscow (Sverdlov Square), 2008. Multi-media Installation. Image courtesy of Yevgeniy Fiks.

YF: Yes, in Moscow especially. In Moscow, there is no history of gays visible anywhere in the city. There, the gay history is invisible, just like Communist history is invisible in New York. No one knows about it, as if it did not exist. Because of this parallel invisibility, I put works about American Communists and about Soviet gays next to each other on the same wall. The invisibility of their respective histories ties them together.

NK: Apart from the places of gay and Communist histories in Moscow and New York, in this exhibition you also showed photographs of gay meetings in Washington DC. There, you photographed these places with a cardboard cutout of a nuclear explosion.

YF: Yes. In this work, Joe-1 Cruising in Washington DC, I photographed a cardboard cutout at the places where gays used to meet or cruise in the capital of the United States.

Yevgeniy Fiks, Joe-1 Cruising in Washington, DC (Franklin Park), 2012. C-print. Image courtesy of Yevgeniy Fiks.

This is a more ironic work, with references specifically to the Cold War. American history here is looked at from a more ideological point of view. These photographs not only document gay history in the United States, they also record the conflation of the histories of Communism, homosexuality, Soviet spies, etc. This is the record of the history of the Cold War and its witch hunts. On the one hand, it is ironic, but on the other, it is something that has factual basis in history. In the beginning of Cold War, Washington DC was “cleared” of suspected Communists and their sympathizers. Gays were suspect as well, because it was believed that they were more susceptible to Communist propaganda than straight men, and that they could be easily blackmailed and coerced to cooperate with Soviet spy networks or Communist cells antagonistic to the US government. The project with nuclear explosions dates to 2012. This was before the political distancing between the US and Russia fueled by the Crimean annexation and the events in Ukraine. However, in this work, I also wanted to show that even though state-sponsored homophobia in the US appears to be a matter of history, it is not too far in the past.

People of my parents’ generation, who were born in the 1930s, could have been victims of this homophobia generated by the American state approximately from the late 1940s until the 1970s. Some of my projects contain criticism of American society, directed in particular at a certain self-satisfaction about the notion of progress. It is true that the results of what is called progress are clearly visible, but it is interesting to remind Americans who are often self-congratulating about the advances in the area of LGBTQ issues of the official persecution of homosexuals in the US merely forty or fifty years ago. Homophobia is alive and well in Russian governmental circles right now. But in the US, it is difficult for young people to believe their ears when they hear descriptions of homosexuals spread around by official channels in the US just a few decades ago. The pages of newspapers at that time frequently mixed hatred of homosexuality with anti-Communism and anti-Sovietism. The state was looking for an enemy.

NK: Also, there is the question of modern art and its reception by the powers-that-be, both in the United States and in the Soviet Union. Apparently, modern art was similarly suspicious if not outright hostile on both sides of the Iron Curtain. I am thinking in particular of your 2012 workTour of MoMA with Congressman Dondero.

YF: On the American side, I viewed this question through the lens of the political leaders’ anti-communism. The history linked to Congressman Dondero is very telling, even though he was an exception with his strong anti-modernist stance. Other political leaders in the US might have been indifferent or neutral in their attitudes. But Dondero maintained that modern art was a communist conspiracy aimed at undermining the foundations of Western society. As someone who was born in the Soviet Union, I think about Soviet nonconformists and unofficial art, and how these artists were considered to be Western puppets. It is an interesting overlay of paranoia in both political systems directed at art that is not easy to understand. Soviet nonconformists may have thought of themselves as oriented towards the West, or maybe they just wished to create art for the new era. At the same time, Conressman Dondero thought of them, and of modern art generally, as agents of Communism.

NK: What place does this show have in your career?

YF: This is an exhibition that combines projects from different stages of my career. It is the first show where I display works that were made 10 years apart from each other. Usually, I just focus on one subject and one project. I combined three different subjects in this exhibition, because I am well familiar with the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union at Zimmerli Art Museum (Rutgers University) and its importance for the history of post-war art in the Soviet Union. When I thought about a project for this museum, the subject of nonconformism came to my mind right away. Besides artistic nonconformism, it seemed important to me to broaden an understanding of this concept. It was important to understand artistic nonconformism as a political gesture—as documented at the Dodge Collection at Zimmerli by many artists and many works—but it was also important to understand other manifestations of nonconformism, such as the sexual and gender nonconformism represented by the LGBTQ community. Political nonconformism (such as anti-Sovietism) sometimes blended with artistic nonconformism, as was the case in the Soviet Union, especially toward the 1980s. Earlier on, some Soviet nonconformist artists may have believed in Communist ideals.

NK: Is this your first personal museum exhibition in the United States?

YF: This is my second solo museum exhibition in this country. The first one-person exhibition took place four years ago at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. It was an art intervention that was built into a museum hall. I would say that this show at the Zimmerli is my first expanded museum exhibition. I think that these subjects are important for the museum to work with in light of their major collection’s focus on nonconformism. It shows that the art movement of Soviet nonconformism was not an isolated instance of a dissident streak in human nature, but that it was part of a larger phenomenon, which manifested itself in politics and in sexual/gender identifications.

Interview with Thomas Sokolowski, Director of the Zimmerli Museum, Rutgers University

Natasha Kurchanova: I am interested in the Zimmerli Art Museum not least because it houses the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Non-Conformist Art from the Soviet Union. With your arrival a year and a half ago, I noticed that the character of the exhibitions changed. Both artists now on view, Irina Nakhova an Yevgeniy Fiks, are contemporary artists; they are not the “old guard” of Soviet nonconformism that forms the basis of the Dodge Collection. I would like to ask you a few questions about the Fiks show, but I am also curious about your vision for the museum at large.

Thomas Sokolowski: You are right, the works on display now by Irina Nakhova and Yevgeniy Fiks are more recent than what has been shown in the past, although both of them lived in the period covered by the Dodge Collection – Irina more so than Yevgeniy. The Dodge Collection is extraordinary; there is no comparable collection even in the former Soviet Union that has so many works from that period (the Cold War). A lot of it was clandestinely brought out of the country. However, especially in the West, some visitors’ reactions to it are reminiscent of the expression “a fly in amber,” because most people here do not know much about those years, particularly when it comes to the former Soviet Union. We knew a lot about the time of the October Revolution and Lenin, but then—partly because of Stalin afterward—the Soviet Union was a closed world, so that it is difficult sometimes for people in the West to understand it. The way I want to open this up is to bring in people like Yevgeniy, who grew up during the Soviet empire, but then moved to this country. Yes, he has a Russian heritage, but you can call him now an American artist, rather than a Russian one. Just like Picasso: Was he Spanish? Was he French? He is an artist of the world, like most artists. The same applies to Irina who has lived in the US for twenty-five years or maybe even longer. It’s nice to be able to have them look back at their past, and also to look back, from the past, without those rose-colored glasses. In Yevgeniy’s case, we are talking more about negative rose-colored glasses, since he is really taking those times for what they were. Sometimes, hindsight is more fifty-fifty than when you are in the midst of it, because when you are in the midst of it, whether it is good or bad, you often do not have the vision to say: “Is it really good? I do not believe that,” especially when we are talking about Russia. You could not publicly say that, because the art could not be shown or you could be thrown in jail or killed.

NK: Irina Nakhova’s exhibition was put together by a curatorial team consisting of Jane Sharp and Julia Tulovsky, whereas the Fiks show was organized by you. Could you say a few words about how you came to the decision to curate this show?

TS: This exhibition is part of a program that we will be doing every summer from now on. We only have two big shows—one in the fall and one in the spring—both running for half a year each. We found that both exhibitions run a little too long and that by the end there are not that many visitors in the galleries. I therefore proposed that we should close the spring show a bit early, on June 1, and that at that point we put up an additional, more performative summer show that would be more like an installation; we do not want to have to move the walls, paint them, or do any other major alteration in the space until the fall. Next year, we will work with a local theater company on a show that deals with the local community. The performances will run during the day and at night for about a month. We really want to activate the museum space. In Yevgeniy’s case, he came up with the idea, which we liked, and which fits the blueprint we developed for our summer show.

NK: What interested you about Fiks’ proposal?

TS: I like the notion of a diaspora. I find it much more appealing than orthodoxy, whatever that may be. Fiks did some shows that incorporate his hybrid Russian/American identity as well as local history within the United States. For example, in my former city of Pittsburgh, he did a show that dealt with the history of communism there. Yevgeniy is an archivist who looks into the history of a place. This appeals to me. So, I brought him here, and we decided that his show would be organized not by the curators in charge of the Dodge Collection, Jane and Julia, but by myself together with Donna Gustafson, the curator of American art. There is a popular notion that if an artist sends his work to a museum, it is dismissed right away. I do not spend hundreds of hours on looking at these submissions, but I do look at the slides in a light box. I would say that over the course of my career, maybe 8 or 10 times I have made a studio visit based on the work that was sent to me. I have a sense of serendipity, and I like to show something new and exciting. I also like edgy things, and Yevgeniy’s work is certainly edgy. We hope to do more of this in the future. For example, Donna Gustafson and Gerry Beegan, the interim Dean at the Mason Gross School of the Arts, are working on a show about the political influence of Angela Davis on art and culture in the 1970s. Right now, we have a show of Khiang H. Hei, a photographer who was in Tiananmen Square thirty years ago, when the killings happened. At the university, we have a large number of students who are Chinese nationals, most of them just one year old when Tiananmen happened. Many of them did not even know that it took place. They thought it was the West slandering China. Now, they have a chance to examine their own history. I want to do more shows like that. For example, when we look at the mid-and late 1960s, as represented by the works from the Dodge Collection, we realize that we in the West are not aware that there was a famine in Minsk, Belarus, during that period. Yet we know very well what was going on in Paris and in the United States at that time: we can say that it was a moment of intense political activism, when young people were engaged and were trying to change things, etc. By tracing historical parallels between the West and the countries behind the Iron Curtain, we hope to make the Dodge Collection more transparent and accessible for peoplewho are not familiar with the Soviet Union or the former Eastern Bloc more generally. There are extraordinary works in that collection, though so much of it is text-based. Which means that if you do not read Cyrillic alphabet, you cannot read what it says…

NK: It sounds like have a global vision for the development of the programming at the museum.

TS: You could say this. I was at a meeting yesterday with other art organization leaders in New Jersey where I talked to my colleague at Princeton University Art Museum. We talked about the fact that Princeton University and its museum can be a mini-Metropolitan in a sense that they can afford to acquire expensive art from any period or part of the world. We do not have this kind of wealth and we cannot offer such an encyclopedic overview of world art. But with the Dodge Collection, in particular, and with the French 19th-century works on paper, we have two vast and unique collections that focus on historically specific areas of art. We have visitors who are coming to see specifically exhibitions related to those collections.

NK: Thank you.

The interviews were conducted over Skype on June 29 and July 7, 2019.