Communism Never Happened at Feinkost, Berlin (Review)

Communism Never Happened, Galerie Feinkost, Berlin. November 7, 2009 – December 20, 2009

For someone whose personal experience of communism does not go beyond its Cold War Hollywood runoffs, curating a show entitled Communism Never Happened might appear a bit out of range. But Aaron Moulton, the director of Feinkost Galerie in Berlin, doesn’t have much of a desire to talk about communism. “I don’t think that’s my job,” he says. “I’ve never even read any Marx.”

For someone whose personal experience of communism does not go beyond its Cold War Hollywood runoffs, curating a show entitled Communism Never Happened might appear a bit out of range. But Aaron Moulton, the director of Feinkost Galerie in Berlin, doesn’t have much of a desire to talk about communism. “I don’t think that’s my job,” he says. “I’ve never even read any Marx.”

Opening the exhibition to correspond with the German capital’s celebration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, Moulton and his partner Mette Ravnkilde Nielsen wanted to critique the type of exhibition that frames a collective memory with only careless nostalgia and empty regurgitations. Communism Never Happened achieves this critique by highlighting the subjective fallibility of the process of remembering: the way our memories distort themselves or are even completely destroyed.

Opening the exhibition to correspond with the German capital’s celebration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, Moulton and his partner Mette Ravnkilde Nielsen wanted to critique the type of exhibition that frames a collective memory with only careless nostalgia and empty regurgitations. Communism Never Happened achieves this critique by highlighting the subjective fallibility of the process of remembering: the way our memories distort themselves or are even completely destroyed.

“I’m really focused more on the ‘Never Happened’ part, rather than the communism,” continues Moulton. Ciprian Mure?an’s 2006 piece that lends the exhibition its title plays directly with the theme of such historical alteration. The phrase is carved from vinyl records created to disperse propaganda aurally. Mure?an’s translation of the function of these objects from sonic to visual begins the chain of revisionism by taking it on actively. The authoritativeness of the statement “communism never happened” reminds us of dictatorial tactics that employed an aggressive and unforgiving historical eraser, capable of removing inconvenient events and individuals from the narrative. The piece sets a frame for the exhibition, explicitly creating a context and describing its goals – Mure?an is not one of the gallery’s artists, but Moulton managed to secure the work, without which this exhibition might not have come to life.

In order to disperse the works that evoke an “aha” moment, Moulton placed Anetta Mona Chi?a and Lucia Tká?ová’s piece All Periods in Capital from 2007 on the other side of the gallery’s dividing wall. The two have created one smooth, black, handmade ball to correspond with each mark of punctuation in Marx’s text Capital– said to be 22,000 in all. Although it is one of the few pieces in the exhibition that seems as though it might not be a structural element, the bag of balls itself is pleasing in its straightforwardness. It also would probably feel good to reach into the bag and feel around.

In order to disperse the works that evoke an “aha” moment, Moulton placed Anetta Mona Chi?a and Lucia Tká?ová’s piece All Periods in Capital from 2007 on the other side of the gallery’s dividing wall. The two have created one smooth, black, handmade ball to correspond with each mark of punctuation in Marx’s text Capital– said to be 22,000 in all. Although it is one of the few pieces in the exhibition that seems as though it might not be a structural element, the bag of balls itself is pleasing in its straightforwardness. It also would probably feel good to reach into the bag and feel around.

Yang Zhenzhong’s 2003 video, Spring Story, maintains the theme of re-filtering and transcribing a leader’s seminal words through multiplication and formal reinterpretation, but this time to a more powerful end. As a recipient of the 2003 Siemens Art Grant, the artist was allowed access to the company’s factory in Shenzhen, one of those Chinese cities that in the past fifteen years have grown from a village of under ten thousand to an industrial capital inhabited by over ten million. In 1992, at the beginning of this exponentially rapid process of expansion, Deng Xiaoping went to Shenzhen to deliver his Southern Campaign Speech. The speech was one of the first gestures towards the idea of the birth of the individual in the Communist nation, and it marked a turn towards the acceptance of capitalism. Eleven years later, Zhenzhong invited each of the 1500 workers at the Siemens factory in Shenzhen to recite one word from Deng Xiaoping’s speech. While the artist allows each worker his or her voice and place in history, he illustrates the fact that the absorption of the capitalist system into communist China has not brought the individuality that Deng Xiaoping promised, but has rather ensured that it will not exist.

Yang Zhenzhong’s 2003 video, Spring Story, maintains the theme of re-filtering and transcribing a leader’s seminal words through multiplication and formal reinterpretation, but this time to a more powerful end. As a recipient of the 2003 Siemens Art Grant, the artist was allowed access to the company’s factory in Shenzhen, one of those Chinese cities that in the past fifteen years have grown from a village of under ten thousand to an industrial capital inhabited by over ten million. In 1992, at the beginning of this exponentially rapid process of expansion, Deng Xiaoping went to Shenzhen to deliver his Southern Campaign Speech. The speech was one of the first gestures towards the idea of the birth of the individual in the Communist nation, and it marked a turn towards the acceptance of capitalism. Eleven years later, Zhenzhong invited each of the 1500 workers at the Siemens factory in Shenzhen to recite one word from Deng Xiaoping’s speech. While the artist allows each worker his or her voice and place in history, he illustrates the fact that the absorption of the capitalist system into communist China has not brought the individuality that Deng Xiaoping promised, but has rather ensured that it will not exist.

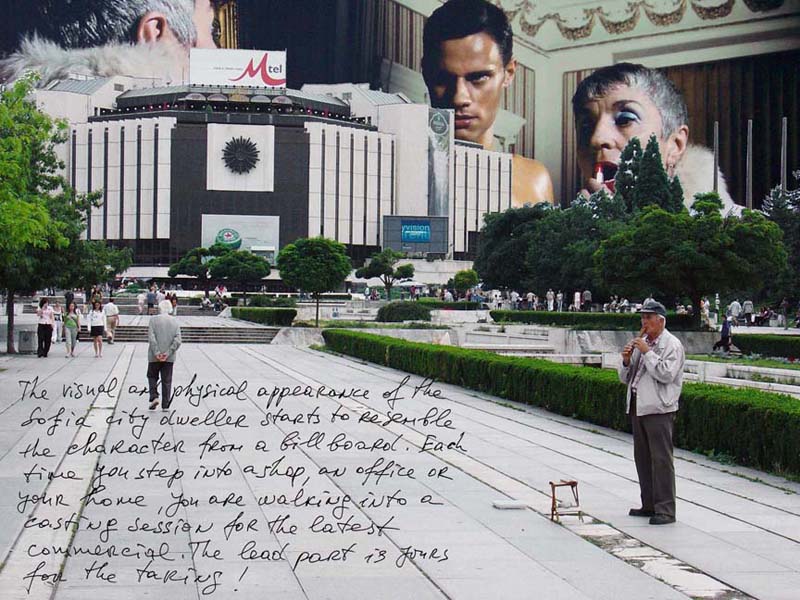

The pieces from Sofia-based Luchezar Boyadjiev’s Billboard Heaven on display examine the corporate appropriation of the quotidian enacted by public advertisements in the artist’s hometown. As part of this process, the individuals in the series of photo-collages are stripped of their autonomy, as they are not enabled to act as individuals but as representations of a population.. Boyadjiev’s analogy fits nicely into the exhibition’s thesis, demonstrating the effect of changing political and financial structures on the public sphere and its individual denizens.

The pieces from Sofia-based Luchezar Boyadjiev’s Billboard Heaven on display examine the corporate appropriation of the quotidian enacted by public advertisements in the artist’s hometown. As part of this process, the individuals in the series of photo-collages are stripped of their autonomy, as they are not enabled to act as individuals but as representations of a population.. Boyadjiev’s analogy fits nicely into the exhibition’s thesis, demonstrating the effect of changing political and financial structures on the public sphere and its individual denizens.

Patrick Tottofuoco is also interested in remapping the psycho-geographical experience. His sculpture Neueröffnung selectively layers the Berlin neighborhoods that aesthetically appealed to him on top of one another, reconfiguring in this way chronology and the historical events that created these geopolitical boundaries. The title, which means reopening or “new opening”, describes the arbitrariness of the construction of these boundaries, as well as an individual’s experience of them.

Julian Bismuth’s piece, composed of various coins of different currencies polished to the point of uselessness and scattered on the gallery’s industrial-looking floor, is another of those elements in the exhibition that seems tacked-on for extra ornamentation. The piece attacks the (art) market by openly displaying the capricious value of these small metal objects that were once worth a total of about five euros and that now sell for next to nothing. “It’s about envisioning alternative economies, universal economies. It’s very Utopian in a way,” says Moulton.

Julian Bismuth’s piece, composed of various coins of different currencies polished to the point of uselessness and scattered on the gallery’s industrial-looking floor, is another of those elements in the exhibition that seems tacked-on for extra ornamentation. The piece attacks the (art) market by openly displaying the capricious value of these small metal objects that were once worth a total of about five euros and that now sell for next to nothing. “It’s about envisioning alternative economies, universal economies. It’s very Utopian in a way,” says Moulton.

Some of the most visually agreeable works in the exhibition were photographs by Sean Snyder and David Levine. Snyder’s work speaks to the process of pre-digital-age archives and their lack of accessibility and legibility. The inclusion of his work in the exhibition was a strategic curatorial move and one that successfully and enticingly rounded off the exhibition’s goals. Levine’s work for the exhibition was a still from his 2007 documentary Bauerntheater (Rural Theater) in which he had an actor, David Barlow, perform as an East German potato farmer. The project as a whole, which was on display at Feinkost earlier in 2009, beautifully outlines a meta-discourse of how an actor begins to inhabit another character, the moments before and after, and the difference between enactment and re-enactment. The still on display at Feinkost is an abstract specter that doesn’t necessarily call to mind the same associations as the entire project, yet it happily functions on its own.

Some of the most visually agreeable works in the exhibition were photographs by Sean Snyder and David Levine. Snyder’s work speaks to the process of pre-digital-age archives and their lack of accessibility and legibility. The inclusion of his work in the exhibition was a strategic curatorial move and one that successfully and enticingly rounded off the exhibition’s goals. Levine’s work for the exhibition was a still from his 2007 documentary Bauerntheater (Rural Theater) in which he had an actor, David Barlow, perform as an East German potato farmer. The project as a whole, which was on display at Feinkost earlier in 2009, beautifully outlines a meta-discourse of how an actor begins to inhabit another character, the moments before and after, and the difference between enactment and re-enactment. The still on display at Feinkost is an abstract specter that doesn’t necessarily call to mind the same associations as the entire project, yet it happily functions on its own.

The least commercially viable and the most nationally inclined work in the exhibition is the REP Group’s aptly titled 2006 project, Patriotism, from which a work in two parts called After the Future, Today Forever is on view. The Kiev-based collective has developed a specifically Ukrainian language of symbols that doesn’t pander to the Western perception of what that might mean. By asserting their nation’s right to self-determination “they are trying to fortify the potential of the local,” Moulton claims. With the help of a dictionary or key, viewers are invited to try and decipher works that often resemble hieroglyphics.

For her 2007 video Exercise, Lucia Nimcova asked several people to perform again those exercises that during the Soviet era they used to do at home every morning as the radio blared the commanding counts to the nation. The work’s power comes from the people themselves who exercised in private, privately performing these improvised, playful motions to the rhythm of collective counts. Nimcova’s reenactment in the video is a touching view into the private sphere and the isolation that this moment entailed for many people, as these motions now become comical out of context and the actors become personalized out of the collective framework. Exercise brings humanness into the exhibition without any pretense, and with an extremely touching effect. The exhibition Communism Never Happened is as heavy-handed as it is understated, and it is Nimcova’s piece that ties it to the ground by giving it a face and offering viewers a hand to hold.

For her 2007 video Exercise, Lucia Nimcova asked several people to perform again those exercises that during the Soviet era they used to do at home every morning as the radio blared the commanding counts to the nation. The work’s power comes from the people themselves who exercised in private, privately performing these improvised, playful motions to the rhythm of collective counts. Nimcova’s reenactment in the video is a touching view into the private sphere and the isolation that this moment entailed for many people, as these motions now become comical out of context and the actors become personalized out of the collective framework. Exercise brings humanness into the exhibition without any pretense, and with an extremely touching effect. The exhibition Communism Never Happened is as heavy-handed as it is understated, and it is Nimcova’s piece that ties it to the ground by giving it a face and offering viewers a hand to hold.

Moulton has described his exhibition as analogical to the steps that patients with dementia or Alzheimer’s are instructed to take to offset their illness; to keep a diary, learn a language, draw a map from memory. These are the very same steps that the artists in this exhibition are taking. The exhibition constructs a powerful commentary that scurries around its subject without feeling like anything is left unsaid. Proving Moulton’s claim that the commercial gallery is now the most liberated of art world institutions, his show is a successful alternative to your average “fall of the Berlin Wall” exhibition.