Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin: Gábor Altorjay

This conversation is part of a series of interviews with artists from Eastern Europe who live and work in Berlin. The city has attracted artists from Eastern Europe for a long time: especially during the Cold War and into the 1990s, its peculiar geo-political situation provided Berlin with a unique flair that attracted artists from all over the world, but especially from the Central and Eastern parts of the continent. How do these artists experience the city today? How do they look back on the hopes and expectations with which they once arrived? Have they settled for good, or are they considering moving elsewhere? Do their Eastern European origins still matter for their art making?

Sven Spieker: You left Hungary in 1967 and came to Germany. Where did you go first?

Gabor Altorjay: To Stuttgart. From there I went to Cologne, then Frankfurt, then Hamburg, and most recently I came to Berlin. When I arrived in Stuttgart in the fall of 1967, I immediately called my friends, especially the Fluxus artist Wolf Vostell. Vostell passed me on to Bazon Brock with whom I immediately organized an action. I had been corresponding with Vostell for a year from Hungary. Through him I also got to know the great Fluxus collector Hanns Sohm, who was a sensational guy. When Vostell found out that I was in the West, he immediately called Sohm. Sohm was a dentist in Markkröningen near Stuttgart. He came to pick me up in his sporty Opel Commodore GS Coupé and took me to his place. That’s where the dental treatment began. Sohm treated all Fluxus artists and took artworks for payment. I once talked about this with the artist Dieter Roth, whom he also treated, and he was not at all satisfied with Sohm’s services. Nobody was! But he was the best art collector in the world. Sohm clearly belonged to the group phenomenon that was Fluxus. He didn’t take part in the group’s events, but he was always part of the party. Wherever even a shred of paper was left from a Fluxus event he would pick it up, he was obsessed! Sohm had a very authentic Fluxus collection that he ended up donating to the Staatsgallerie Stuttgart. He would never have sold anything from his collection.

SS: What were you up to with Brock in 1967, after your arrival in Stuttgart?

GA: Shortly after my arrival, we met at the pub of a leftist student union (the famous SDS) in Stuttgart where Joschka Fischer, who later became leader of the Green Party, was behind the bar. The audience was expecting a Happening from Brock, perhaps one of his famous lectures delivered standing on his head. However, Brock did not want to meet these expectations; he just sat down and gave a perfectly boring academic lecture. Meanwhile, I stayed in another room and listened, but couldn’t understand a word. I heard screams and whistles. Shortly afterwards, Bazon came to me and said: “your turn.” So I went out and entertained the eighty-odd 20 to 25-year old listeners by dividing them into groups according to their weight and making them shout different things. There was a lot of applause. I was new in Germany and didn’t want to be booed off the stage right away! And I enjoyed it. The next day after this event, Sohm took me to the Frankfurt Book Fair. We drove on the Autobahn at 105 miles per hour. I was scared. We stayed at the Book Fair for three days. All the important Fluxus people were there, from Emmett Williams and Ben Patterson to Dick Higgins and his wife Alison Knowles who made her famous walk-in book. They all exhibited with the Typus publishing house that was run by Franz Mohn. He published all the Fluxus artists in the ‘60s. That’s how I got to know all of these people, through Sohm. Almost all of them were ten years older than me.

SS: Did you see yourself as part of that scene?

GA: Not really. Nobody wants to believe this today, but Fluxus basically only existed from 1961 to 1963. Those were the years when this group, which consisted of strong individual artist personalities—Naim June Paik, Vostell , Al Hansen, Dave Higgins, George Maciunas, Robert Filiou, and, on the margins of the group, Dieter Roth—was active under this umbrella.

SS: Who particularly impressed you at the time?

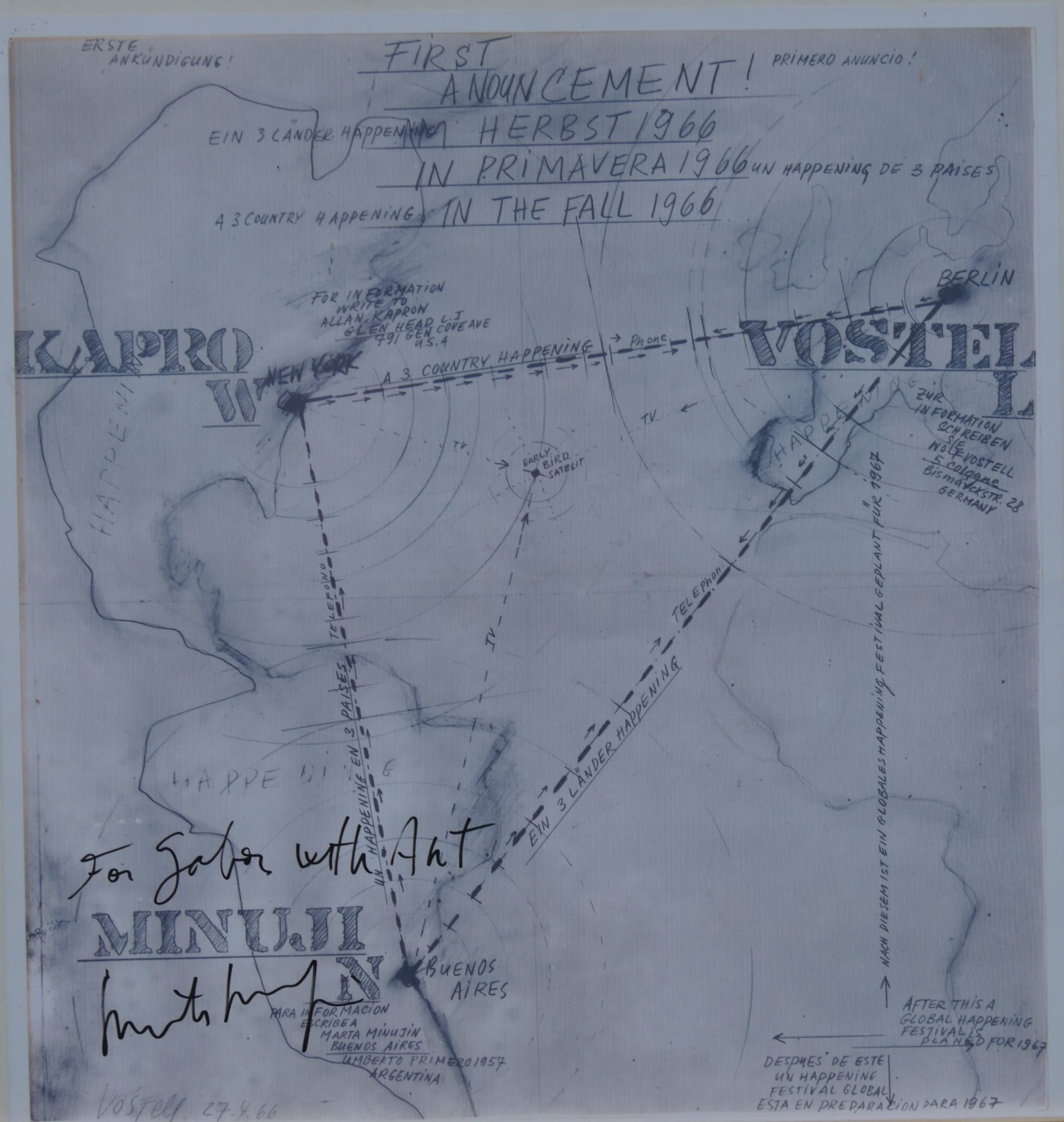

Announcement for Marta Minujin, Three Country Happening (1966). Image Courtesy of Gábor Altorjay.

GA: A bunch of people were always needed for the Fluxus actions, so the artists took part in each other’s events. For example, in 1966, Marta Minujin, whom I admired very much, conceived the twenty-four-hour Three-Country Happening together with Vostell and Kaprow. The idea was for several Happenings to take place simultaneously in New York (Kaprow), West Berlin (Vostell), and Buenos Aires (Minujin). Each artist contributed an idea for one Happening that would then be carried out by the other two simultaneously. Kaprow, for example, covered a Cadillac with cream and a well-known pop band licked it off. The artists’ Happenings were to be broadcast live over the first commercial satellite, “Early Bird.” However, the problem was that Vostell and Kaprow only carried out their own actions without bothering with the other two. Only Marta performed all three.

SS: Did you have any further contacts with Minujin?

GA: In 1967 I designed a Happening for her, 15 Actions for Marta Minujin. It consisted of instructions such as: “Listen to 2 operas at the same time.” 40 years later, in 2007, it was performed at the Budapest Art Academy. Marta came to Stuttgart from Argentina in 2009, on the occasion of the exhibition Subversive Practices. The show was about art under dictatorship. There we performed Meeting Marta Minujin and The Five Pregnant Virgins. We danced for a few minutes. Three years later there was M.M.M. 2 in Berlin with General Pop.

SS: By the time of the 1967 Book Fair in Frankfurt, Fluxus had ended?

GA: Yes, exactly. And ten years after that, Fluxus was resurrected. But for artists like Vostell, Fluxus was done at the end of the ’60s. As a group it had broken up anyway.

SS: Did you share the Fluxus artists’ understanding of art with its emphasis on playfulness and anti-commercialism?

GA: Absolutely. Even when I was in Budapest and became aware of the Fluxus group for the first time, I understood that they were so to speak related to each other. And they treated me as a relative, too! When I showed up at the Book Fair in 1967 I could neither speak German nor English; I knew Polish, but nobody understood that. People knew what I was doing, but above all there was a spiritual kinship between us, and with Vostell, maybe even love. They were very warm, friendly, and completely free people. They knew that in the East and in the West, we all shared the same zeitgeist, and that’s how we found each other. In 1969 Immendorff invited me to a show in the West German city of Trier together with Beuys’ Art Academy class. I scattered mothballs all over the museum, while Immendorf challenged the museum director to a wrestling match. At that time I was reading Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s first book, Left Radicalism: A Violent Cure Against the Aging of Communism. It dealt with revolutionary movements, the anarchist movement, and the Parisian May. It was when I read this book that I discovered for the first time that communism is not necessarily something bad, that you can be a communist without being a communist, so to speak. It also made me feel that maybe art isn’t relevant anymore.

SS: How did you end up in Cologne after Stuttgart?

GA: In the spring of 1968, four months after I left Hungary, through Vostell. I got an apartment in the Catholic student hall of residence for refugees from Hungary. A few months later, the Stockhausen student Johannes Fritsch and Vostell rented an apartment in Cologne together. I moved in with them. Above me was the studio of the pop group Can, the most important German band at the time. The building belonged to a Greek doctor. At the time, Cologne was not yet the international art center it would become in the ‘80s. In 1968 the city administration allowed us to create our own anti-art market in a huge parking garage that had not opened yet. There we could do whatever we wanted: Vostell put down his railroad tracks while Paik exhibited his rigged piano, and I washed myself with Kvass and Coca Cola.

SS: In the late 1950s and ‘60s, Cologne had a reputation for being avant-garde.

GA: Yes. It all started at the end of the ‘50s, in the studio of Stockhausen’s later wife, Mary Bauermeister. The first Fluxus concerts took place there in 1959, for example with Nam June Paik. In 1962 Stockhausen founded his electronic music studio, which the West German Radio Corporation (WDR) set up for him, and that’s where he began his sound experiments. Cologne had a great reputation then. That ended when it became a trendy art city. In 1968 I founded Combine #1 with Mauricio Kagel and his wife, Fritz Heubach, and Alfred Feussner. At the time I called myself “Short Circuit Bricklayer.” I basically built walls, sometimes with built-in binoculars. There was also a wall with green ski pants built into it, and another one with a sponge. One of these walls was made of slices of bread for mortar. Vostell told the renowned gallerist René Block about my bread wall. And in 1970, when Allan Kaprow came to the Fluxus & Happening retrospective in Cologne and also visited West Berlin, he built a bread wall there! I didn’t even find out about this until 20 years later.

SS: Were you part of the Fluxus retrospective in Cologne?

GA: No, I didn’t want to take part, it was too museum-like for me. For me, a Happening began where art ended.

SS: Why did you decide to stop making art?

GA: The point was that art no longer seemed necessary to me, no longer relevant. Already in 1971, I had become a member of an anarchist group; more precisely we were syndicalists. That means, we were neither Maoists nor Marxists. On May 1st, 1971, forty of us demonstrated on a square in central Cologne. Across from us were the Maoists, in the middle the trade unions, and at the very front, with his Mao Bible in hand, was my friend the painter Jörg Immendorff. Even with him it was no longer about art: Immendorff created propaganda paintings at the time. Between the spring of 1968 and 1971 I spent a lot of time with him and his brilliant wife, Chris Reinecke. And in 1971 we all finally said: Fuck art, it doesn’t work, it doesn’t help.

SS: Did you have contact with other Eastern European artists in Germany?

GA: Not really. There weren’t that many. Artists still went more to Paris than to Germany. Eastern European artists were often completely disoriented in the West, especially those over 35. When a Hungarian came out, they usually contacted me immediately. I was a point of contact for information. Many of them, often older than me such as Laszlo Lakner or Imre Bak, became my friends and wrote me long letters. In 1968 I also met Tadeusz Kantor in Nuremberg at an exhibition, and we spent a couple of days together. I noticed his paranoia: he did not want to cross the street for fear of being run over by an informer or a spy. I then went to Frankfurt, where I stayed until 1979. At the time I was not allowed to go to West Berlin because of my refugee status. I went to West Berlin only once before 1979.

SS: The United States were also important to you. In what way?

GA: I always wanted to go to “American” cities. Until the end of the ’70s I thought I would stay in Germany only as long as the Americans were there. I was a leftist, but never an anti-American, on the contrary. I was very anti-Nixon, but not anti-America, despite all the grievances. I read the Black Panthers every week. And from 1970 on I often went to the USA. Back in the early 1960s, in Hungary, I really felt that the US were the future, they had Marylin Monroe, Kennedy, etc. But the trial of Bobby Seal, when he was gagged and tied to his seat, that was too much, that was not ok. We just really liked Seal and his people. We organized a demonstration in Cologne where we wrapped a large pig’s head into a US flag and shouted: “Freedom for Bobby Seal!” Of course, no one there even knew who Bobby Seal was, people just kept walking.

SS: Did you consider this action art, or politics?

GA: It wasn’t art. Art was no longer relevant for me. Art simply lost importance in the face of the bombing of Laos and Cambodia.

SS: Art ended for you when you were in Frankfurt?

GA: I didn’t make any art in Frankfurt. Instead I became a freelancer for the local state radio station. Vostell sometimes still sent cards, and I did, too. This lasted into the ‘80s, but we no longer met. I didn’t know what to say to him, I was no longer part of the gang. From 1973 on I organized a news service called Agency for the Dissemination of Missing News, a mouthpiece for the leftwing underground. People sent us information and we published it on a weekly basis. For example, we were early supporters of the anti-nuclear movement, and we distributed transcriptions of speeches by important left-wing politicians.

SS: Were you interested in the situation in Eastern Europe at the time?

GA: Yes, very much so. In fact, the idea for our news agency was related to this. In the early 1970s there was some intellectual resistance in Hungary and Poland, and the Hungarian writer György Konrad was particularly important in this. These people were hoping to connect with the New Left in the West. For example, they published Miklos Haraszti’s book about his depressing experiences in a Hungarian factory. The manuscript was smuggled out of Hungary and when a copy of it was found in Konrad’s oven, Tamas Szenbtjoby (with whom I was still close friends at the time) and Haraszti were promptly put in jail. The Wagenbach publishing house in Berlin published the book under the title Stücklohn (Piece Wage).

SS: Did you think the communist system could be reformed? Did you believe in a better communism?

GA: Absolutely. That was the nonsense of those years, but it only lasted a short time, from about 1968-1974. Then came the expatriations of Biermann and Solzhenitsyn, and a wave of arrests in Hungary. In 1975 practically all of my friends were kicked out of Hungary. I was allowed to re-enter from 1979 on, because in the meantime I had received German citizenship. During the 1980s I was often in Hungary, even when the most important people, such as Szentjoby or the members of the Squat Theater, were no longer there. The Squat Theater was very successful in New York before it perished. The 1980s were an interesting period in Hungary, and I got to know other, younger people.

SS: What about your relations with Miklos Erdely?

GA: He was 10 years older than me, but Szentjoby and myself, we inspired him. Above all, we introduced him to Happenings. He did have very good information, not least from Paris, but we—only in our early 20s at the time—were more daring. We sat in his piano. At the end of the ’70s, I made a Super8 film about a Happening by Erdely.

SS: What was your relationship with East Germany?

GA: None at all. East Germany didn’t exist for us. South Korea was closer than East Berlin. We didn’t even know where Pankow was, and nobody was interested. In 1983 I made a Science Fiction movie for German TV and called it Pankow ’95, as in the East Berlin suburb of Pankow where the apparatchiks lived. The film was set in East Berlin and Nicaragua. Pankow was meant to be an alliteration of “punk.”

SS: You left Frankfurt and came to Hamburg. Why?

GA: In Hamburg I wanted to help set up the Dankerrt Theater. Hamburg was really interesting during the ’80s, a kind of Eldorado. I spent 20 years there, the longest time of all the cities I have lived in. I made films. Hamburg and Berlin were rivals back then; rivals also in depravity! They had a few people in Berlin like Iggy Pop and David Bowie, and we in Hamburg had Bryan Ferry and Neger Kalle. Berlin was probably more debauched, but Hamburg wasn’t bad, either. If I had to name a city I call home, it would be Hamburg.

SS: And Berlin?

GA: I came to Berlin in a roundabout way, through a fellowship in Budapest. There I began to write a book, Factual Legends I. 1949-1979. It’s a memoir that deals with the connection between youth culture, contemporary art, and political movements. The manuscript was supposed to be finished in 2008, coinciding with the 40th anniversary of 1968. Here in Berlin I basically feel like an exile from Hamburg. It was clear to me from the beginning that I would not participate in the art world in Berlin. For Vostell, this had been completely different since he basically carried on in Berlin with what he had been doing in Cologne. But those were the ’80s, when everything in West Berlin was exciting. By the way, at the end of the 1990s, I met Vostell again, here in Berlin, and we made a lot of plans. But nothing came of it. He died three months later.

SS: How did you get back into art?

GA: Between 1980 and 2000 I was only involved in film, mainly film production. In 1993 the Artpool archive in Budapest invited me to participate in an exhibition. It was called 3 x 4, with Szentjoby, Erdely, and myself. Each of us showed four works from the ’60s and ’70s. I showed my Short-Circuit Box. The Hungarian National Gallery purchased it. That was my first exhibition in a long time, and it was curious to be involved with art again. I then gathered everything that was left over from my old Happenings. Of course, that’s ironic because Happenings are not supposed to leave anything behind! After the Artpool show I gradually started being involved in art again. I was disappointed with cinema, and politics didn’t offer me much either. And so I got back into non-commercial art. The problem was that in the meantime everything had become commercial. That’s how I ended up with popcorn. Popcorn is what I have dealt with over the past 15 years. I wanted to create something that is absolutely non- commercial as art.

Gábor Altorjay, Popcorner (Museum Ludwig. 2008). Image courtesy of Gábor Altorjay

For me, popcorn is not only absolutely authentic, it is also cosmically significant: each popcorn is its own Big Bang! However, now poor General Pop has suffocated in his popcorn-filled coffin …

SS: Thank you very much!

Berlin, 2017 (Translation by Sven Spieker)

Other interviews in this series:

Nika Radić