László Beke (1944–2022): A Collective Obituary

László Beke, the Hungarian curator and art historian who from the late 1960s became one of the key catalysts of art networks and cross-border collaborations within and beyond Eastern Europe‚ died on January 31 of this year. He published articles, compiled publications, lectured, curated projects and exhibitions on various aspects of progressive art, including Conceptualism, photography, semiotics, Fluxus, Dada, and the post-contemporary (referring to the situation after the era of contemporary art), and, most importantly, pursued his utopian commitment to East European art. Between 1969 and 1986 he was a research fellow at the Research Institute for Art History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest. During this time, he also organized and initiated several significant projects, most notably in György Galántai’s Chapel Studio (1972–73), in the Club of Young Artists (1974–77), and in the framework of the Society for Popular Education. One of his groundbreaking projects was Imagination, launched in August 1971, in which Beke asked twenty-eight Hungarian artists to send him documentation regarding their artistic imagination which—according to his premise—equaled artworks. Another project he organized during these years was Tombstones and Paving Stones (1972), which interpreted stone as an artistic medium fusing the “weapon of the proletariat” iconography with that of tombstones understood as embodiments of popular beliefs in the hereafter. He also served as a Hungarian or regional correspondent, advisor, and co-curator for such significant art events as the Paris Biennial of Young Artists (1973-77) and the 1979 Sydney Biennale, and for the exhibitions Europa, Europa—Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, in Bonn (1994) and the travelling exhibition Global Conceptualism, New York, Minneapolis, Miami (1999–2000). He held other academic posts, including guest professor at University of Lyon 2 (1988–89), professor at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (1990–2022), and director of the Research Institute of Art History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest (2000–12). He also served as curator of the Hungarian National Gallery (1988–95) and as director of Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle in Budapest (1995–2000).

We remember László Beke in a special way through the collected memories of some of his contemporaries, colleagues, friends, and students.

Dóra Maurer, artist, Budapest

Hot summer, sun-bleached grey street view from above. I look down from a south-facing balcony. I see László Beke on the street corner heading to Buda Castle, rushing to his workplace; he is toting art publications and documents in his fat-stuffed briefcase.

In 1968, I was in Vienna for half a year with a consular visa. During this time, the Hungarian avant-garde burst into flower in Pest, and a lot of artists of my age or even younger, who I had not know, not even by sight, had emerged. The movement was organized by Péter Sinkovits, (Hungarian art historian, organizer of the famous Iparterv exhibitions in 1968 and 1969, with the participation of Imre Bak, András Baranyai, Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics, Ilona Keserü, László Lakner, János Major, Ludmil Siskov, Tamás Szentjóby, and Endre Tót, among others.) but its éminence grise and initiator was Laci Beke. At that time, concept artists (mainly from abroad) and Beke, who did not separate the conceptual/performative and artistic activities, gave us “assignments,” inviting us to do thematic projects, which made both of us [Maurer and Tibor Gáyor, Maurer’s partner] glad, and we created our still seminal works, action-documenting photo series by these impulses.

We got to know the painter, Ludmil Siskov (Ludmil Siskov was born in Bulgaria but left to Hungary in 1956 and studied painting in the Budapest Art Academy. He moved to Vienna in the early 1970s.), a member of the Iparterv group in Vienna. We often met him and his wife, graphic artist, Mari Koncz, and through them, we got acquainted with the Hungarian painter, János Megyik, who lived in Vienna since 1956 and graduated from the Vienna Art Academy. Milcsó [Ludmil], the person of contacts, gave us the phone number of the graphic artist, András Baranyai (Hungarian graphic artist and photographer, member of the Iparterv Group.), who came to visit us with Beke. We had already made our paving stone series, and we gave them to him.

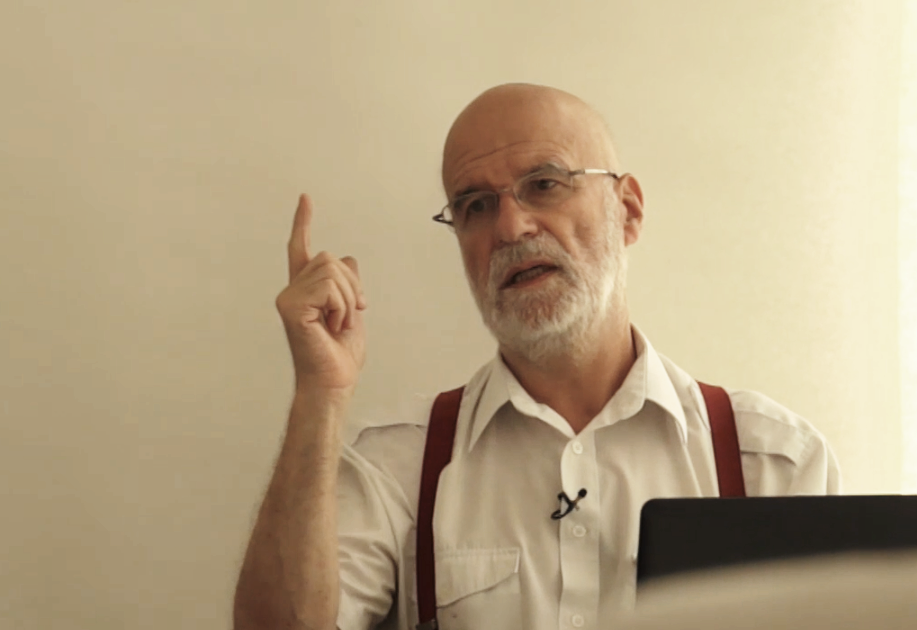

Dóra Maurer. What Would We Do With a Piece of Cobblestone?, 1971. This work was also featured in Beke’s Tombstones and Paving Stones collection. Image courtesy of Dóra Maurer.

It was summertime; the sun bleached all the colors. We lived opposite Buda Castle in Viziváros. When Laci left, we watched him from the balcony, heading to the castle with his heavy bag burdening his shoulder, rushing to his workplace, the Art History Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, of which he was later director. (The Research Institute of Art History founded in 1969 was one of those many cultural institutions that after the WW II was housed in the historical buildings of the Budapest castle. Almost all these cultural institutions were moved out from these buildings in the 2010s.) At his eagerness, toting avant-garde art to the castle, we smiled cordially.

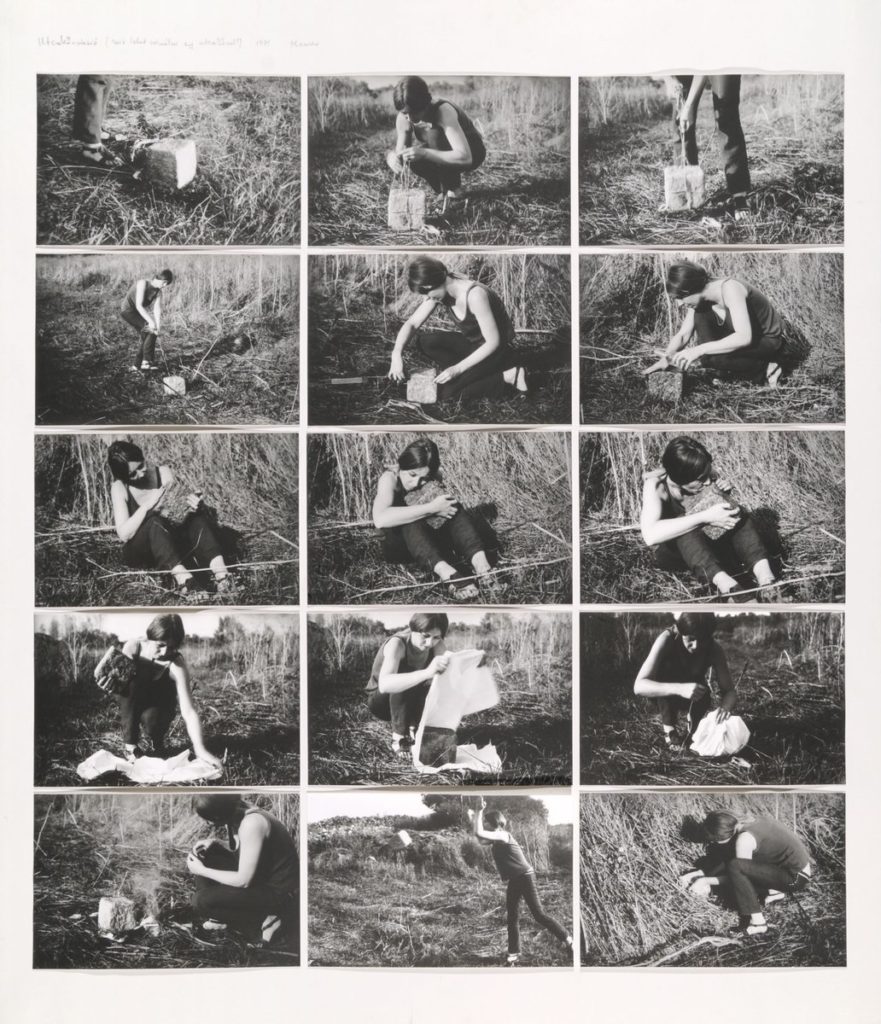

Imre Bak. Process Object, 1971. Image courtesy of Imre Bak.

Imre Bak, artist, Budapest

I would like to remember László Beke with a work I contributed to his very successful Imagination project.

Process Object, 1971.

The adaptation of a motif from a medieval house-wall in Essen-Werden, West Germany.

The object consists of three, 2 x 3 meter pieces, one leaning against the wall, one lying on the floor, one broken into sections. The object was made of varnished PVC foil, stretched over wooden sections (with intense reflection effects.) Exhibited: Folkwang Museum Essen, Germany, September 1971.

Rudolf Sikora, artist, Bratislava

I first met László Beke in person in 1968. László welcomed the liberation of society and culture in Czechoslovakia “socialism with a human face.” Culture, including visual art, began to open up and cooperate with the world in Czechoslovakia, and so visual relations with Hungary began to develop stronger and more meaningfully. László had an above-board relationship with us.

After the occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the period of “normalization” started and all artists’ contacts with the world began to be severely curtailed. At that time, meetings with Hungarian artists helped us a lot, thankfully we were still able to travel to Hungary.

I cannot forget the meeting of Czechoslovak and Hungarian artists in August 1972, organized by László in the Romanesque church in Balatonboglár on the shores of Lake Balaton. It was a meeting that was created as a remembrance and apology on the fourth anniversary of the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact soldiers in 1968. Part of the event was a legendary action of shaking hands between the participants, who included: Vladimir Popovič, Gindl, J. H. Kocman, Valoch, Pospíšilová, Stano Filko, Rudolf Sikora, Peter Bartoš, Petr Štembera, Filková, Sikorová – Imre Bak, László Beke, Péter Legendy, László Méhes, Gyula Pauer, Tamás Szentjóby, Béla Hap, Péter Halász, Péter Türk, György Galántai, Ágnes Háy, Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics.

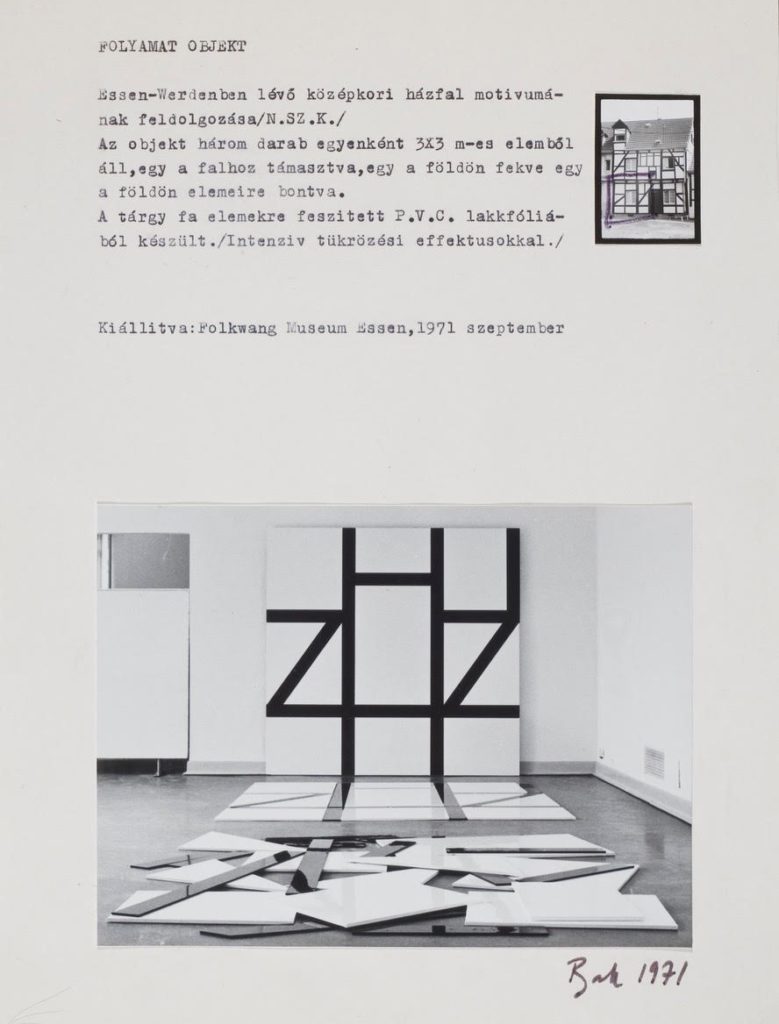

László Beke (seated left) at the Meeting of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists in György Galántai’s Chapel Studio in Balatonboglár, 1972. Image courtesy of György Galántai and Artpool Art Research Center.

Unforgettable for us were the frequent discussions and exhibitions at Fiatal Művészek Klubja (Club of Young Artists) Budapest. László had also prepared personal exhibitions for us at the club. I remember my own with Jozef Jankovič, Juraj Meliš and the authors of the White Space in White Space (Stano Filko, Miloš Laky, Ján Zavarský). It was these rare contacts that allowed us to go further abroad.

After the regime change in Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1989, László continued to acquaint international audiences with the forms of conceptual art in the countries of the former Eastern bloc.

In 1991 in Budapest, I met László again at the important exhibition Oscillation, Slovak and Hungarian Art Festival in Műcsarnok (Oscilácia/Oszcilláció/Oscillation: exhibition of artists from Hungary and Slovakia. Curators: Zuzana Bartošová, László Beke, and Tamara Archleb Gály, Šiesta Bašta, Komárno and Műcsarnok, Budapest, 1991.). Later, we continued to meet at various exhibitions around the world.

In 1999, László co-curated the exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s at the Queens Museum, New York. In Slovakia, we met in 2009 at an international conference in the Slovak National Gallery dedicated to the work of Július Koller representative of Slovak conceptualism, and again in 2015 at the BAC / Bratislava Conceptualism conference (Could We Speak of “Bratislava Conceptualism”?).

László Beke will forever remain my personal friend and friend of the Slovak art scene.

Ioan Bunuș, artist, Târgu Mureș, Romania / Meaux, France

I’ll share one of my most vivid memories of the late László Beke, whose sad death has taken him to the “beyond.” It was the year 1986 (or 1987?), in Paris, where I was living with a very good friend, the photographer Lajos Somlósi. Beke was there too and, after breakfast, the three of us headed “to the city” without any plan. When we arrived at a certain central point, Place Saint Michel, László asked me where I would like to go. Since it was a beautiful Easter Sunday, I proposed: “Please come with me doctor to Notre Dame (it’s not far away),” according to the tradition.

The huge cathedral was in all its splendor that Easter day, completely full of people, as was the city of Paris. As our luck would have it, we got the last empty seats, right near the red carpet of the main axis. At the end of the ceremony, the impressive closing hymn passes with great retinue, through the smoke of incense, next to us was Cardinal Lustiger (the famous archbishop of the era). I see László, who sat there kneeling very proper, touching, with the gesture of an ordinary mortal, the golden stole of the Cardinal. The Cardinal turned his gaze to “célèbre homme de Dieu” (what a look!) towards László, who was standing there making a figure of an apostle “de passage á Paris.” The deep repentance, respect, and admiration László felt were visible on his face more clearly than any of his texts on art, and the holy man blessed him. In that extremely rare moment, the superior spirituality triumphed within this ambitious man, a man of great renown (to us), a renown won through his assiduous progressivist activity conducted in another great capital city (of a still divided Europe), Budapest. There are no appropriate words or comments to describe that moment. Astounded, I witnessed the scene up close—like a painting of Rembrandt!

I’m a Christian and I’m convinced that God, in his immense kindness, will remember those two European apostles, one from the West, Cardinal Lustiger, and the other from the East, our late László Beke.

Irina Subotić, art historian, Belgrade

We knew each other very well. We had met several times in Budapest, where I had organized the exhibition, Avant-garde in Yugoslavia: The ZENIT-age 1921–1926 (Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest, 1986), also at some AICA conferences, and when he was in Belgrade and Zagreb. Our encounters were very fruitful for me as we had similar interests in the avant-garde(s) and contemporary art. He was an important art critic and serious art historian—a kind of symbol of modern Hungary.

Călin Dan, artist and curator, Bucharest

With László Beke’s death, a whole era, and a complex one, is coming to an end without too much noise.

Beke was the brilliant product of the no-less brilliant Hungarian school of art history, an institution that managed to maintain, despite the dire circumstances installed with the Cold War, the high standards and the sophistication inherited from a discipline consolidated during the dual monarchy of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Typically, Beke started his scholar path as a hard-core art historian, with a master thesis about the gold background ornaments of medieval panel paintings, a study expanded later with a doctoral dissertation on medieval goldsmith works. His interest in the period was followed unabated throughout his long career, in parallel with a similarly consistent interest in modern-contemporary art, where he became very fast a cult figure.

This unexpected and rare capacity of covering with competence and enthusiasm such diverse domains remains the defining quality of Beke as an intellectual. He sensed with accuracy the uniqueness of the Hungarian art scene during the 1960s and 1970s, when a whole group of artists, writers and theoreticians were involved in sophisticated conceptual discourses, while operating in an authentic underground manner. This appealed to the scholar in Beke, but most importantly, it was fitting the subversive, quirky, un-submissive dimension of his inquisitive mind. The comfortable silence of the library was not enough for Beke, who also needed the excitement of studio visits, of long conversations in non-academic corners, of exhibition openings and social events.

While a thorough researcher and writer, Beke was still not your usual art critic. He had to be in the thick of the action, and that is how his reputation crossed the border from Hungary to Romania, and that is how I first met him. Beke was, in the true spirit of the historical avant-garde, an internationalist and a traveler, binding different zones and personalities of the region. It was thus just half surprising when, one afternoon in the mid-1980s, he entered the editorial room of Arta magazine, to meet his friend, architect, Mihai Drișcu. I was hanging there, a young and naive debutant, looking in awe at the two men, both bespectacled, both with grey beards, both moving and speaking slowly, in a broken mix of French and English.

Their conversation was fascinating, and I remember Laci (as he was called) becoming passionate about the mysticism of Hugo Ball, and about the glossolalia quality of the Dada performances. There was an intensity in that small art history excursion and I realized suddenly that Beke was a religious person, adding another layer to his complex personality. Because next to all the sophistication of his encyclopedic mind, Beke had the no-nonsense dimension of a small clerk from an even smaller puszta village, growing a family, and going about his menial daily tasks. After the political changes of 1989, we met constantly in various professional occasions, and there I could enjoy even more, probably in contrast with the cosmopolitan environment, his modest demeanor. Wearing unmistakable grey sweaters, with an unflinching smile, Beke was always ready to launch with a soft voice in some half-delirious, provocative discourse about an urgent discovery he made about the tortuous developments of contemporary art.

Beke’s career has been driven by a childlike restlessness and by a relentless curiosity. He liked to surprise the entourage with his ideas, as he liked to change the direction of his focus. Always alert to new currents, Beke successfully embarked, from the late 1980s on, in the promotion and analysis of the art and technology movement, which he was seeing probably as a follow-up to the neo-conceptual period, to which he contributed in substantial ways. As he himself implied with amusement, on one hand he was protected from the communist party officials by the prestige of his scholarship, focusing on the burgeoning Hungarian national identity within a larger Europe. On the other hand, his active belonging to the underground scene made him interesting to the same officials, who in the 1980s were testing a local version of perestroika.

Due to this delicate balance, Beke was able to fulfill several institutional responsibilities, and to support long-term policies—what he called the canonization of the neo-avant-garde. In that sense, he was not only a realist, but also a visionary—feeling the directions where art history would develop in the post-Cold war era. Even his nonchalant visits to the Bucharest based Arta magazine were part of this attitude. He was curious about the developments of the local art scene and was narrowly following the work of such elusive artists like Ana Lupaș, whom he supported with discretion. In unassuming ways, he was also a reference figure and a messenger of normality for the avant-garde scene of Romania during the peak of dictatorship. At that time, it was almost unbelievable to see a colleague from the neighboring socialist Hungary nurturing an international career beyond the Iron Curtain, travelling abroad, communicating with peers from everywhere. Young and mid-generation artists, art historians and art critics in Romania were seeing the Hungarian way of doing business as an envied model, and within that context they were looking at Beke as a point of reference, and of hope.

The works of Paul Neagu in the exhibition Macrotrans-Representation: The Week of Romanian Art, organized by Sorin Dimitrescu and László Beke, Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest, 1998. Image courtesy of Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest. Photograph by József Rosta.

It came naturally that during his tenure at the Műcsarnok, Beke returned (so to speak) the favors and organized a monumental exhibition of Romanian contemporary religious art, in collaboration with the Anastasia Foundation (1998). While for the local avant-garde friends this project came as a disappointment, the choice was actually fitting of both the spiritual dimension of Beke’s intellectual profile, and his appetite for the unexpected, exotic manifestations of visual arts. Once again and in his own twisted way, Beke was right: at that time, the orthodox trend was the most original contribution of Romanian art to the international context.

The complicated context in which Beke reached remarkable goals is adding value to the achievements of this wise man. As he leaves us, we should remember the times when Central Europe was—despite communism—a place of creativity, invention, and humor. And we should hope to return to those qualities—for us and for the memory of those discrete fighters, of whom Beke himself was an important one.

Luchezar Boyadjiev, artist, Sofia

I met László in Kraków, Poland, in the spring of 1991. It was so early after the fall of the Wall, that although I knew a lot about the world and the art around the world, I had no idea about art in Eastern Europe. The occasion—the exhibition Europe Unknown and the parallel conference (Europa nieznana / Europe Unknown, Pałac Sztuki TPSP, Kraków, 1991, curated by Anda Rottenberg. New Horizons of European Art, AICA conference, 1991.), were not only eye-opening and mind-boggling experiences for us, a couple of artists/curators from Sofia who had little idea about the modern and contemporary art of Eastern Europe. This was the stage for forging life-long and career-long friendships, new allegiances, and the setting of a coordinate system of values in art and art history, which is still there. Among those people I met, too many to list here, László Beke stood out (although only thirteen years my senior), with his impeccable, no-nonsense attitude, full of dignity and aura which combined human presence, professional expertise, and unquestionable authority plus a sense of humor. All of this emanating softly from the bold head of a master who, although we did not meet as often as I would have liked in the years since, was always a reference point for me. No! A reference pillar!

Installation view, Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s (April 28, 1999–August 29, 1999), “Eastern Europe” installation organized by László Beke, Queens Museum, New York. Image courtesy Queens Museum, NY.

Needless to say, I was very happy when in 1999 the essay he wrote on conceptualism in Eastern Europe came out in the catalogue of the groundbreaking exhibition Global Conceptualism at the Queens Museum in New York (1999). The point is—I was mentioned by name—briefly and a bit undeservedly because we in Sofia started out too late “to matter” for inclusion in the show itself. And yet – what a generosity of art historical vision aiming at inclusion rather than exclusion. I believe that the long and productive career of László is full of many such examples for his contribution to who and what we are today.

Mária Chilf, artist, Budapest

László Beke, Professor Beke, Laci

Thirty-two years ago, at the Budapest College of Fine Arts (where I was his student), he made us write a test: what is décollage? Everyone write! Everyone wrote. I sat over the paper and the words did not come. He was already gathering the papers when I suddenly folded the sheet of paper in half, tore a cloud shape out of one half and drew a landing plane on the other half. He took it right out of my hands. I haven’t written my name on it yet, I said, he looked at it and said no problem, I’ll remember.

He taught us, tested us, opened my exhibition, our exhibitions in Budapest, Berlin, Cluj-Napoca, Târgu Mureş. He gave last honors to my husband, Gábor Szörtsey, together with Ágoston Vilmos in the Kerepes cemetery. He was present in our lives with the natural directness of a family member.

A series of memories strikes me, but now that I have to write this text, I just sit in front of the computer and the words don’t come again …

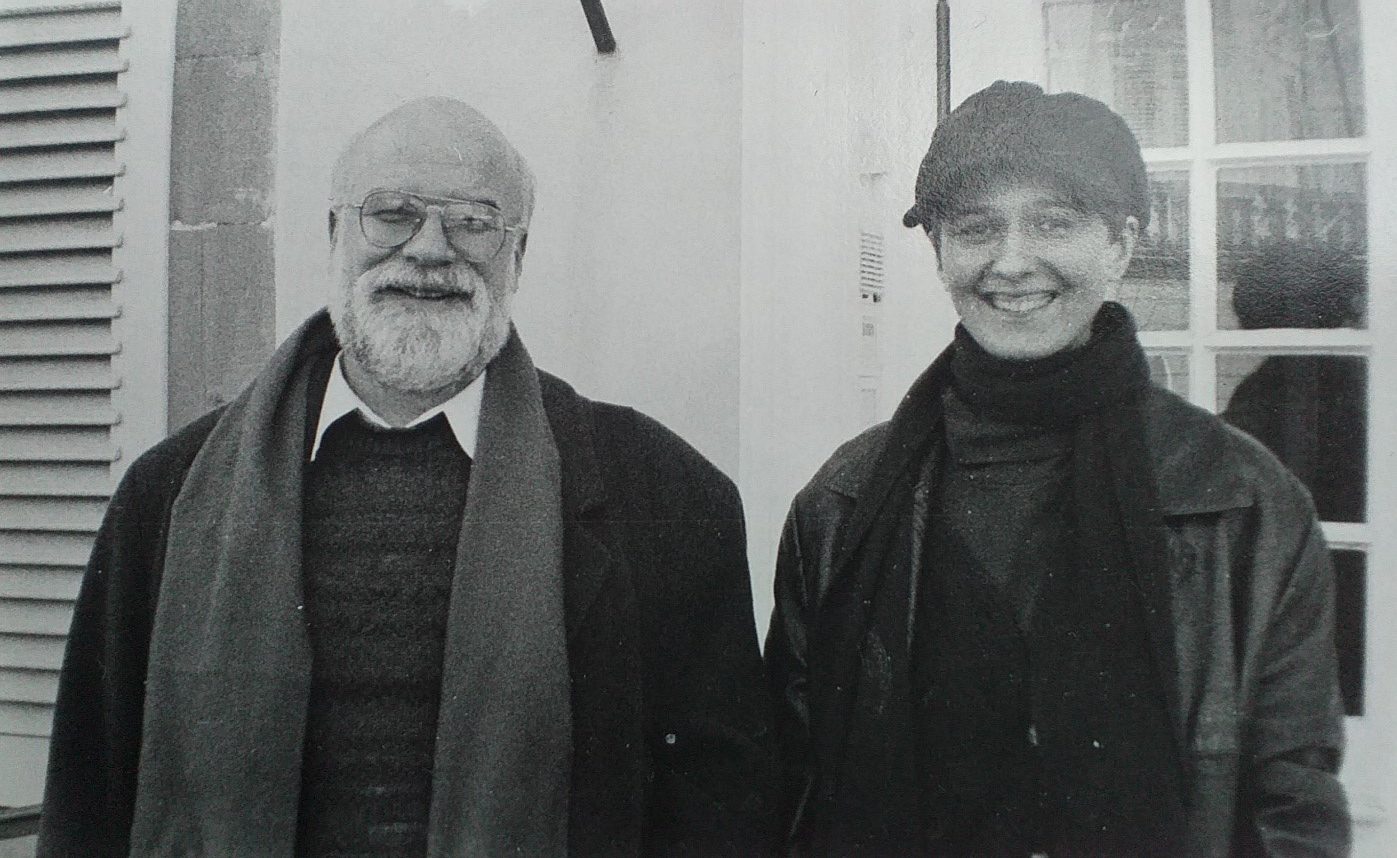

László Beke with Mária Chilf in Stuttgart, 1996 Image courtesy of Mária Chilf. Photography by Jean-Baptiste Joly.