The Glitzy World We All Think We Want: An Interview with Zornitsa Stoyanova

Zornitsa Stoyanova is a performance artist working between the United States and Bulgaria. Currently based in Philadelphia, Stoyanova performs under the name Here[begin] Dance, and her practice involves the creation of large-scale props in front of her audience. Her work explores an amalgamation of genres, blending choreography, performance, song, and shadow play. This summer, Stoyanova took part in Etud and Friends, a dance and performance festival held in Sofia and one of a growing number of multidisciplinary events that seeks to bring together local and transnational artists and performers working in a variety of disciplines.

While Bulgaria hosts multiple dance festivals every year, contemporary performance in the country still has a niche audience. In an attempt to engage broader audiences, theater festivals in Bulgaria have recently sought to focus on activism in the arts. For example, ACT Independent Theater Festival—now in its ninth year—seeks to engage state institutions on questions of legislation and aims to provide opportunities for freelance artists to produce independent, autonomous theater. ACT envisions a future of more diverse performance practices developed through the participation of new and active audiences, and through support from international performance networks in Western Europe (and particularly Berlin). Alongside larger performance festivals like ACT, smaller ones have also emerged, sampling unique programs of new and established performance artists. Etud and Friendsis one such festival. ETUD Foundation, responsible for the festival’s organization, was founded in 2005 by Ani Collier, an established Bulgarian artist who started as a ballet dancer and later turned to photography, collage, and video art.

At the 2019 edition of Etud and Friends, Stoyanova presented her work Un-seen, which examines how context transforms the “shiny materials” of Western economy, where immigration and dehumanization are tightly enmeshed. In this interview, the artist speaks about the significance of festivals like Etud and Friends, her own artistic vision, and her exploration of performance from an immigrant’s perspective.

Margarita Delcheva: What is unique about the Etud and Friends festival, and what kind of artists does it bring together?

Zornitsa Stoyanova: Galina Borissova, the organizer of the festival, and I met in the summer of 2018 and discovered a shared interest in performance bordering theater, dance and installation art. She invited me to participate in Etud and Friendsfestival later that year. The festival usually presents work by Bulgarians living outside of the country and other international or Bulgarian long-time friends of Galina and Ani Collier, a Bulgarian expatriate living in the US. In 2005, Ani founded ETUD Foundation and later opened a gallery with the same name. What is unique about Etud and Friends festival is the diversity of work presented, which completely blends genres. It is spectacular to witness eleven days of performance that borders between theater, dance, choreography, opera, and visual art. Galina and Ani know every artist personally and this brings a special kind of cohesive aesthetics to the curatorial process. I found all the work interesting, deeply invested, and very engaging.

Zornitsa Stoyanova. Un-seen, 2019. Performance, Sofia. Image courtesy of the artist.

MD: You have said that your piece Un-seen, presented at this year’s festival, traces the history of the use of Mylar as a material. At one point during your performance, you were inside the Mylar inflatable, which expanded to fill the entire stage and even crossed the boundaries of the dance floor. When it wavered in its enormity, it seemed like a silver whale swimming. There was something frightening and awe-inspiring about it. How did you begin working with Mylar, and what aspects of the material do you explore in your performance?

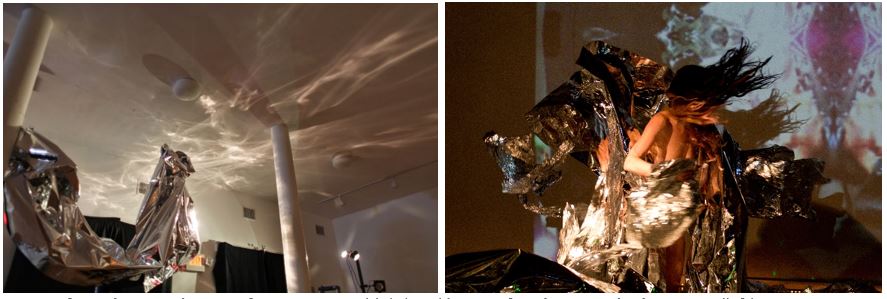

ZS: In 2016 I did an open studio rehearsal as part of Derida Dance residency in Sofia, but Un-seen is actually the first fully realized performance I’ve presented in Bulgaria. I started working with Mylar in 2012 while working on another piece called shatter:::dawn. I was looking to create a clean, beautiful and crystalline set for the show, and I remembered seeing emergency blankets. I purchased the blankets and a lot more of the thicker industrial Mylar and started playing with it. The set for shatter:::dawn was simple, with lots of the material strung from the ceiling made to reflect light and cast interesting shapes in the space. When shatter:::dawn ended, I was four months pregnant with my first child and I took a long break from making and performing. When my son turned six months I started going to our basement and photographing and filming the Mylar from my set. I played with it, shining different lights and lasers, bunching it and using long exposure photography. My next full-length piece Explicit Female (2016) used primarily Mylar and dealt with the trauma, disillusionment and alienation of becoming a mother. During the process of making Explicit Female, I also created multiple dance films with Mylar and a full collection of photographs.

Left: Zornitsa Stoyanova. shatter:::dawn, 2013. Performance. Right: Zornitsa Stoyanova. Explicit Female, 2016. Performance. Images courtesy of the artist.

When I started working on Un-seen, I first constructed a Mylar balloon. I had seen a performance with a big balloon (not Mylar) and realized that it was probably the only thing I had not yet done with Mylar. Initially, I made it out of eight emergency blankets and kept experimentally adding to it. The last version, which was performed at the festival, was made out of twenty-four emergency blankets. For me, the balloon holds many metaphors and symbols. One is the Bulgarian children’s song… “the balloon is inflating….” In the song, kids sing holding hands until they say “puk” and all fall to the ground to signify the breaking of the balloon. It’s a version of “Ring around the Rosey,” another children’s song originating from the time of the Black Death in Europe. Cute, yet a very ominous signifier of lost hope and destruction.

While fully inflated, the balloon is shaped like a giant pillow. It is meant to look both inviting and horrific. The shape refers to the saying “make your own bed and lay in it.” After writing the text that an automated voice performs during this section of the performance, I wanted to make the pillow feel monstrous and engulfing. My goal was to make the audience viscerally sense the shiny pillow’s inherent danger and grotesqueness. Mylar in this piece is a metaphor for the glitzy Western world, and in Un-seen, I try to present it in both its beauty and monstrosity.

MD: Could you comment on the sound and text recordings you used in Un-seen? You mentioned during the post-performance discussion that some of it was comprised of real recorded screams of children. Yet, some of the recordings also seemed quite technical. How do you envision the combination of these different registers during your performance?

ZS: All the text in the performance is written by me and performed by automatically generated male voice with British accent. This initially creates the illusion of a David Attenborough nature documentary. I am very interested in the automatic and robotic voice because it allows no humanity, coloring or emotion to come though, thus the text gets performed in its purest possible form. Though my choice of what kind of robot performs it, I essentially choreograph the experience. The text read by the robotic voice traces the use of Mylar in space and on Earth. It talks about astronauts being protected by the horror of open space by this material and its use by the US government to wrap forcefully separated children from their parents at the US/Mexico border. To me the irony is huge. Astronauts are the best of us, the smartest and most fit engineers and scientists. I draw a parallel between them and the children of immigrants who are hopeful for a better life, only to end up in a cage, without their parents, but still wrapped in this same material. My choice of how the text gets performed here is designed to hint at multi-layered oppression and colonialism that still exists today.

Zornitsa Stoyanova. Un-seen, 2019. Performance, Sofia. Image courtesy of the artist.

Closer to the end of the performance I incorporate the recording of the children held in the US/Mexico border detention centers. Being an immigrant myself and a mother of two little boys, I keep thinking about the random differences between me and the immigrant families fleeing South America. Every time I hear the recording, I cry. Yet, the thought of this injustice doesn’t cross my mind until I am in rehearsal. This issue becomes invisible to me (and I’m sure others) as I go about my daily life of raising my own children, whose biggest issue in life is not having yet another ice-cream. This is the reason that I decided to juxtapose the recording of the crying children with the funny and upbeat YouTube hit song from the 70s by Soviet Union’s Eduard Khil, called “Trololo.” This juxtaposition is particularly interesting to me as “Trololo” is a product of the height of communism, another form of oppression. Those two sounds positioned next to and on top of each other signify so much history, so much oppression, and so much irony all together. Communism is part of my upbringing and being a child during those times, I was blind to its oppressive nature. The effect I want to create through all of the chosen sounds is to bring forth the duplicity that all people in the free world experience. After all, most of us just keep moving though our daily life, uncaring and forgetting the suffering of others, Trololo-style.

MD: At one point during your performance of Un-seen, you were dressed in a black cape, resembling a Grim Reaper figure, then later you transformed into a karaoke singer who enthusiastically begins and then keeps losing her voice. You described these images as archetypes. What attracts you to working with archetypes and how does your audience react to these figures?

ZS: I use archetypes and their recognizable more popular versions because they are a part of me. In experimental performance recognizability is key. When I make work, I want the audience to experience something relatable; an “in” into the work that allows them to see themselves or people they love. I think a lot about building compassion and how to make people who don’t know me, care enough in order to experience emotion. Using archetypes is just one of the tools in my arsenal. Others are telling personal stories, asking for favors on stage, or being funny before being tragic.

Zornitsa Stoyanova. Un-seen, 2019. Performance, Sofia. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Grim Reaper is also the Hermit from the main arcana of Tarot. I am particularly excited about the dual image and meaning of this. The Hermit is the bringer of light and change, but the way I hold my light is like holding a bomb detonator. At the beginning, I am both the Grim Reaper and the Hermit, the lone figure that both illuminates and destroys. My transformation into the karaoke singer is slow and full of doubt. For a while, I sing words from Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” out of order. I repeat and make different meanings out of them, before the karaoke music starts. The song was a huge hit, coming out in 1983, only a year after I was born. I use it as a bookmark for pop culture of the 1980s that is so full of hope and energy. In 1983 Bulgaria and the whole of Eastern Europe was still under communism. Singing parts of “Sweet Dreams” for me signifies a lot of history of hoping, dreaming, wanting to be better, but also not knowing what this “better” is. As the lyrics say: “Everybody’s looking for something.” I love the nostalgia this brings, yet the lyrics performed then meant something different than when I deconstruct and perform them now. The fact that it is karaoke is also significant. Karaoke for me is the ultimate act of fakeness. It embodies the desire to be famous and adored, bundled in self-irony. My inability to sing the actual song is my disillusionment with the desire to be something “more.” I put make up, dress up, even wear the green crown of the statue of liberty, but my disillusionment persists. I can’t ever build up to the glitzy image of what I think I am supposed to be. The green crown of the statue of liberty is the two-dollar foam fake, that every tourist buys when going to visit the statue. I end up being dressed in all these signifiers of fakeness, trying to act in a certain way and never succeeding. This manifested desire to be part of the glitzy world for me becomes a sad play of pretend.

MD: Could you speak about how working with interdisciplinary performance has enriched your work? Do you see a blurring of the boundaries between theater, dance, performance art, and film in the pieces you create? Is it useful to experience the mixture of genres as heterogeneous, or does your work strive to transcend the separation of genres?

ZS: As a working artist, I struggle a lot with the interdisciplinarity of my work. It seems that US audiences and presenters always search for a way to describe my performance and it never quite fits into the molds of theater or dance festivals. In Europe, the words choreography and dance are used in a much broader way, so I would simply be called a choreographer. That said, while making performance I ask what the work needs. I preoccupy myself with what action on stage would translate what I am trying to say. Sometimes the answer is text, sometimes song, sometimes the moving body or video. It all fits like a puzzle and the performance becomes more elaborate or more interdisciplinary, if you wish, with each new edit. I make performance and I hope that I manage to convince curators and presenters to see it as one integrated experience instead of trying to separate out all the genres it could belong to.

Stills from Zornitsa Stoyanova, Elsewhere, 2019. Digital video, 7:20. Images courtesy of the artist.

MD: You are a filmmaker and your short films Geometries of Time, Dark Matter, and Elsewhere were also presented at the festival. Elsewhere was filmed on two continents, including in the mountains of Bulgaria. How does the film reflect your own transnational existence as an artist? And has your work with film changed the way you approach live performance?

ZS: Elsewhere has been in progress for almost three years and is very much a process-driven film about shifting identities and locations. The film is autobiographical in an abstract and psychedelic way. It traces my disillusionment with the U.S., my shifting identity and evolving body image and the feeling of not belonging anywhere in particular. Since having children, I’ve started working on performance in a different way. Materials and research outside of the studio are major factors, so film and photography often precede moving in the studio. First, I create the staging and the scaffolding of the performance before choreographing the movement. This way of working is forced purely because time is very short for someone with two young kids. Yes, I have been influenced from my process of filmmaking, but I’m mostly influenced by the time constraints that my life has at the moment.

MD: Though you live in the US and you performed for a festival in Sofia, we are conducting this interview in Berlin. Could you say more about what aspects of its culture bring you to this city? Do you ever think of Berlin as a unique symbolic location where Eastern Europe and the West come together culturally? Perhaps now, 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there is also a new resonance of the idea of “walls” in the world, a question, which, it seems, your work touches upon as well.

ZS: Berlin for me is the capital of experimental performance and art. Having visited many times, I’ve always experienced art that deeply resonates with me. There is no question that Berlin also feels like home. With its identical to Sofia apartment blocks, the architecture brings both nostalgia and hope. After the fall of the Wall the city is so multicultural, with food and people from all over the world. I find this incredibly inspiring. I don’t believe in creating walls between people and that’s why living in the U.S. right now is particularly difficult for me. I believe in equal education and opportunity with a healthy mix of social capitalism.

As for a new resonance of the idea of “walls,” I see people, including myself, make walls in all aspects of their lives. It happens when a person perceives a lack of something, be it security, education, money, land, food, sexual orientation, you name it… There is a perceived border around it dividing what is mine and what is another’s. My piece Un-seen on a personal level is dealing with my own perceived otherness. I hope that as we (I) humans evolve, we (I) will start perceiving our lives from a place of abundance. I hope that in the future we (I) won’t need to feel like we have to guard our beliefs, homes, food, land, sexuality, work, or social interactions. After all, we in the Western world, and I include Eastern Europe here, throw food away at almost every meal. What is this, if not extreme abundance?

MD: In your work you engage with the position of refugees who face an increasingly complicated and hostile environment. Having lived half of your life in Europe and half of your life in the United States, how do you relate to these two different contexts and their respective practices and projections, regarding the refugee crisis? You’ve also acknowledged struggling with the question of your own privilege as an immigrant artist. How do you approach this struggle in your work and which geographic context prevails in your questioning?

ZS: I haven’t yet lived in the US for as long as I have lived in Bulgaria. In the past few years I have realized that I am mourning what could have been if I had stayed in Bulgaria. I am experiencing a deep loss of identity, not ever feeling Bulgarian or American. I think this is the case for most first-generation immigrants. Working on Un-seen, I tried to imagine what it would be like if I were a refugee. I imagined being hopeful and crossing a border only to have my children be taken away from me because I am not a US citizen, even though their father is. I read stories of that exact thing happening to others.

I’m very aware of the different national narratives that the US and Bulgaria have. Bulgarians are still buried in deep corruption and suffer from residual Ottoman and communist trauma, both psychologically and financially. In the US, the narrative is one of colonialism with all its problematic facets. In the US, 98% of the population is a descendent of a colonist, an immigrant, or a refugee. Each and every citizen has their own identity and idea of what it means to be American. When I came to the US in 2002, I learned that I was white. (I am a dark-haired, dark-eyed, olive-skinned Bulgarian, and always thought of myself as dark). This tells you much about the lack of diversity where I came from, as well as the extreme desire engrained in the US culture for separation and definition. It took me more than ten years to understand and feel “white guilt,” “wealth guilt,” or “privilege guilt.” My father was born in a barn next to the animals and my mother came from a solid middle-class family, who couldn’t afford to buy meat, and they never feel guilt. After communism they traveled the world, and the success of their businesses made them into what many Americans would consider upper middle class. In straddling my two national identities, I question why I feel this adopted guilt, and ask myself if it at all useful. What do I do with my guilt? What do I do with my perceived privilege? Why do I even think I have privilege?

There are no solid answers to these questions for me and I process them by making art about my identity, my loneliness, my guilt, shame and feelings. I think the US population is all suffering from identity crisis in some shape or form. Forgotten and erased histories, multiplicity of beliefs, plethora of incredibly varied cultures, Americans’ only national identifier seems to be capitalism. I definitely question politics in the US more. Maybe this is my own bias for thinking that my small corrupt country just can’t do much better and the US should and could be at least more welcoming to refugees because of its history.

This interview took place in Berlin in August, 2019.