Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell at the National Museum of Mexican Art

Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, March 22 – August 18, 2019

Artist Laura Aguilar died of kidney failure in April 2018, shortly after her career retrospective, Show and Tell, closed at the Vincent Price Museum just outside Los Angeles. She was 59 years old. As writers and fellow artists mourned the loss, biographical references proliferated. Aguilar was obese, an auditory dyslexic, clinically depressed, Latina, mostly poor, the daughter of mixed Mexican-European-indigenous parents, a lesbian. With her photographic work, she was a champion for marginalized communities and bodies rendered invisible by mainstream art and visual media.

A year after her death, Show and Tell has traveled to the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago. Curated by Aguilar’s friend and one-time teacher Sibyl Venegas, the exhibition offers a thorough account of an artist who consistently struggled with the tools most readily at her disposal—the camera and her own body—to make sense of her place in the world and the broader forces acting upon it. As presented, her work consists almost entirely of portraiture and self-portraiture, in both video and still photography. We see it develop from early street shots and intimate portraits of Latinx people in East LA, where she spent most of her life, to deconstructivist photo-text hybrids and confessional-style videos, to a culmination in the works for which Aguilar has become best known: dreamy photographs of the artist herself, posed nude in the landscape.

With its devotion to framing Aguilar’s work with her struggles with self-acceptance, the retrospective offers a compelling suggestion of art’s potential to visualize the personal nature of identity-based political struggles, such as the ones that raged in the late 1980s and early ’90s when Aguilar was producing much of her work. Moreover, it does this in a manifestly intersectional way, showing how Aguilar centered her body in an analytical framework that mapped the varying prejudices, identifications, violences, and insecurities that played out on and within it. If the exhibition has any shortcoming, it is that its biographical focus partially obscures the actual mechanics of Aguilar’s art—what it does and how, where it fits or doesn’t, what real-world and artworld discourses it connects to or disrupts—as opposed to merely what it represents. In so doing, the exhibition misses its chance to situate Aguilar in an even broader context that transcends the specifics of her experiences, central though they were to her work.

Other than some coursework at East Los Angeles Community College, Aguilar learned most of what she knew about photography through self-education and an informal network of friends, mentors, and collaborators. The show’s earliest works are Aguilar’s photographs of members of the East LA Chicano art scene of the 1980s. Here, she presents a sensitive view of artists, writers, and musicians drinking in bars, posing on street corners, and celebrating the Day of the Dead. Although they predate Aguilar’s more conceptually nuanced photo-based works by a few years, these photographs attest to her early faith in the role photography can play in defining a community, however loosely. Ephemera and other materials from the artist’s personal archive are also on view, including a poignant assemblage made in homage to her friend, the poet Gil Cuadros who died from AIDS in 1996, and a card from the 1985 exhibition 7 Latin Photographers at the Self-Help Community Gallery, a key institution in the formation of the Chicano art movement.

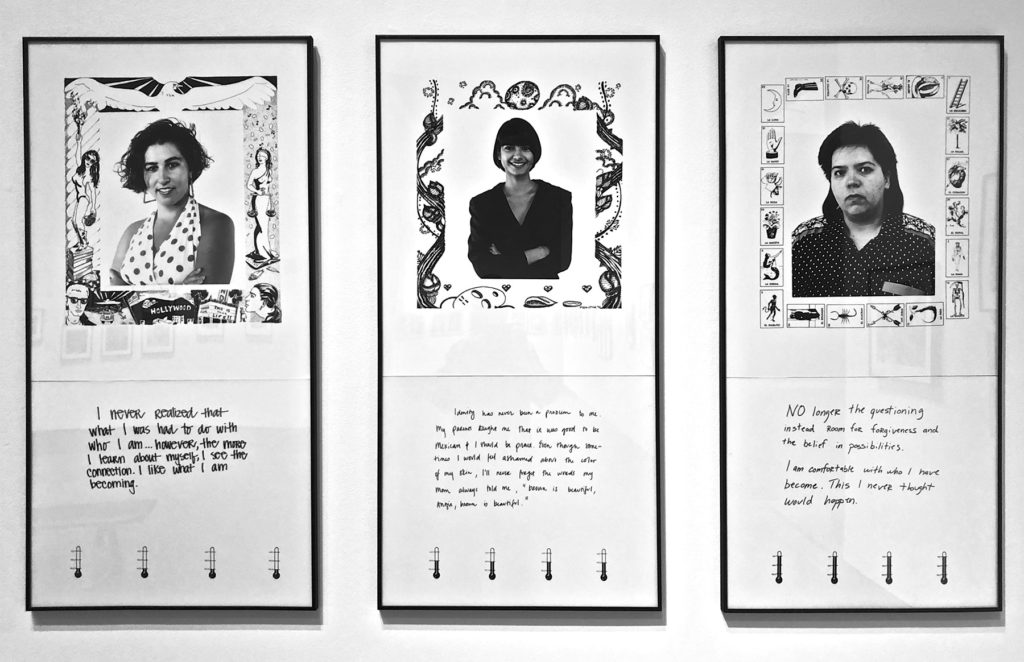

Figure 1: Laura Aguilar, from “How Mexican Is Mexican,” 1990, gelatin silver prints. Courtesy of the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016 and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Within this earlier work we also find evidence of Aguilar’s burgeoning interest in more explicitly analytical explorations of identity through conceptual self-portraiture and the use of photo and text in tandem—decidedly postmodern strategies pioneered by artists since the late 1970s. Her Will Work For series (1993), for example, depicts Aguilar holding signs of protest in public spaces, making demands for access, employment, and health insurance. While co-opting a more conventionally activist idiom, the works show Aguilar experimenting with post-structural or conceptual photography, setting herself in dialogue with artists like Adrian Piper, Barbara Kruger, Lorna Simpson, or Sharon Hayes, who also invented critical, feminist modes of imaging identity and political resistance in the 1980s and ’90s. Like these artists, Aguilar located a radical, wide-reaching power in the simple act of centering images of the female body in institutional space and discourse. Her tactics are more blunt in How Mexican is Mexican (1990), a set of three triptychs that pair photographs of Aguilar and other women with statements reflecting on their relationships to their own Mexican and Chicano heritages. A tongue-in-cheek salsa thermometer measures the degree of Mexican-ness in each subject.

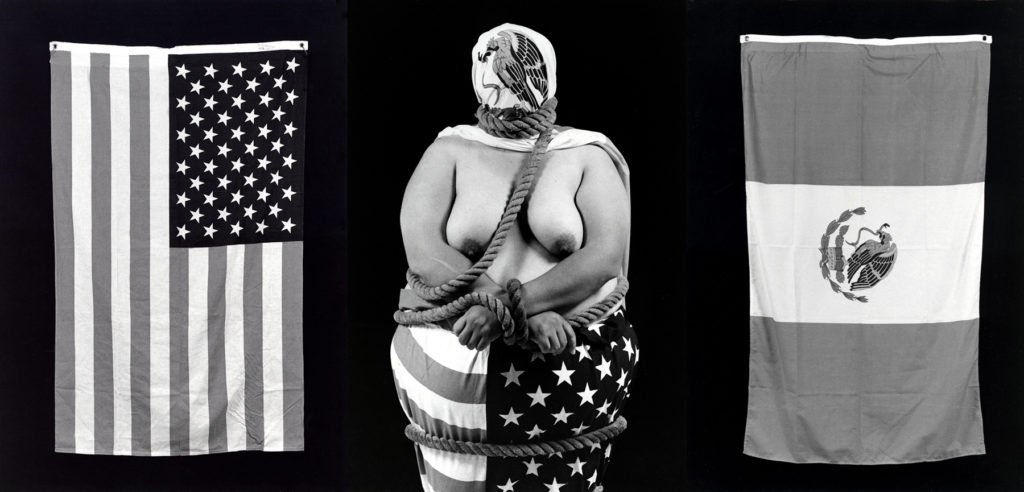

Figure 2: Laura Aguilar, “Three Eagles Flying,” 1990, three gelatin silver prints, 24 x 20 inches each. Courtesy of the Estate of Laura Aguilar and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. © Laura Aguilar.

Aguilar is at her most strident in Three Eagles Flying (1990), a photo whose “three eagles” comprise the national emblems of Mexico and the United States (invoked by their flags), and Aguilar herself (the Spanish word for eagle is águila), shown partially nude and bound by both flags and a thick, coarse rope. With its immediately legible symbolism, the brutal work shows Aguilar adapting the postmodern self-portrait to fit her own needs, through the invention of a new iconography for which her body became the vessel, a tool with which she could speak to broader questions of national belonging. Aguilar didn’t only produce incisive work using her own body, however; in the Latina Lesbians series (1986-89), she photographed portraits of Latina-identified queer women in Los Angeles, which she paired with brief handwritten statements from the subjects speaking to their identification or lack thereof with the signifiers “Latina” and “lesbian.” At once structured and deeply affective, the work suggests a symbiosis between individual stories and collective experiences. Aguilar included a portrait of herself in this series, a reminder for viewers that as centrally as she figures in her oeuvre, her experiences were also collective.(In fact, Latina Lesbians was also included in Ondine Chavoya’s 2017 exhibition Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., a groundbreaking project for its emphasis on networks as a foundational vector for artmaking, particularly by minority groups in times of political turmoil.)

As the works turn increasingly structural and analytical, some of the questions left unaddressed by the exhibition begin to become more apparent. Show and Tell does well to show Aguilar’s formal strategies and tell viewers about her personal experiences and struggles. What at times feels insufficiently addressed is the connection between the two—the significance of how Aguilar used her art to adapt critical and conceptualist strategies to communicate her own struggles and to connect them with broader structures and problems. In other words, was Aguilar more noteworthy because of her experiences, or because she used her art to speak about them?

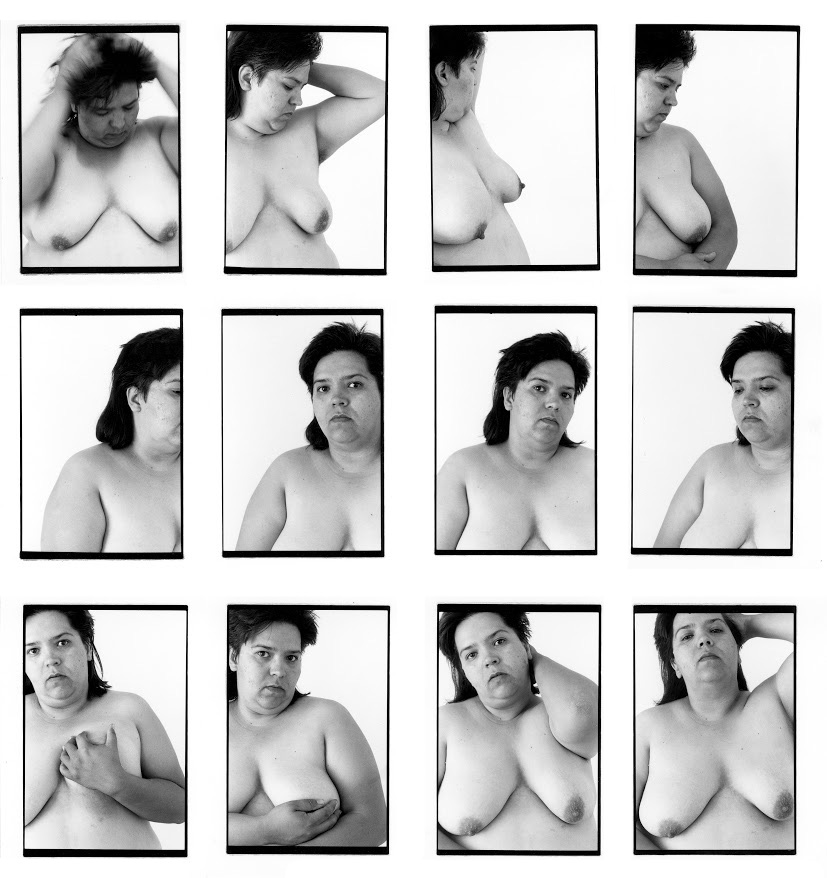

Figure 3 Laura Aguilar, “12 Lauras,” 1993, twelve gelatin silver prints, 24 x 17 inches each. Courtesy of the Estate of Laura Aguilar and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. © Laura Aguilar.

The densest and most nuanced section of the show features two large-scale groupings of self-portraits and a looped projection of three videos. 12 Lauras (1993) comprises twelve studio photographs of a nude Aguilar shot from the chest up. The didactic describes the works as showing “an emotional range where Aguilar is at once vulnerable, strong, sexual, and empowered,” but the variations from photo to photo are subtle, with nuanced shifts in pose and expression. The work seems just as much invested in seriality and repetition, exploring how the photographing of a person can turn them into something abstract, even immaterial. Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt (1993) uses a related tactic to address the struggles with pain and self-acceptance that characterized Aguilar’s life and practice throughout the 1990s; the four-part work documents the progression of a smirking Aguilar wearing a t-shirt that reads “art can’t hurt you” to an image of her nude, eyes closed but seemingly alert, with a gun pointed into her mouth.

The videos produce some of the most revelatory moments of the exhibition, not only for their brutal content but also for the artist’s remarkable formal choices. It is both jarring and beautiful to hear the artist’s voice and see her body in motion, given that in most of her work she has reduced herself to a still or invisible presence. The Knife (1995) shows a cropped view of Aguilar’s hands playing with a knife, clenching its blade, stroking its surface, and pushing its tip against her palm without ever quite puncturing the surface of the skin. Over the tense sequence of gestures plays an audio recording of Aguilar’s soft deadpan voice speaking about depression and exploring the possibilities of self-harm. In The Body 2 (1995), Aguilar presents herself nude to the camera and speaks frankly and casually about daily life inside her large body. She grabs at her flesh as the shot pans slowly down her torso. She stands before the camera with an easy, matter-of-fact self-possession.

In her essay in the exhibition catalog, Amelia Jones argues for a “radical vulnerability” in Aguilar’s work that offers the “possibility of exposure, as well as a strategic mode of intervention into conventions of portraiture.” She continues: “Rather than fragmenting and multiplying the subject into a splintered array of personae … Aguilar, by making us work to relate to the people depicted (particularly herself), makes us aware of our own mutability and vulnerability, always in relation to these myriad modes of identification.”(Amelia Jones, “Clothed/Unclothed: Laura Aguilar’s Radical Vulnerability”, in Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, ed. Rebecca Epstein, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press: Los Angeles, 2017, p. 39.) While it is entirely possible that this empathetic mode is how Aguilar’s images work for some viewers, the videos suggest that there is something else going on—an assertive presentation of a self, faults and all, that demands no acceptance nor understanding. This is who Aguilar is and how she feels, these are some possible reasons why, and the viewer can do what they will with it. She says little to suggest she cares. In turning the agency back on the viewer, Aguilar recreates the mechanisms by which phenomena like racism and fatphobia exist external to her or any one individual.

Figure 4 Laura Aguilar, “Grounded #111,” 2006, inkjet print, 14 1/2 x 15 inches. © Laura Aguilar / Courtesy of the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016 and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

The final galleries of the exhibition are given over to four series of photographs of the artist posed nude in the landscape. Perhaps, having deconstructed her identity and body for so many years, Aguilar was ready to be whole again in front of the camera. The images from Center (1996), shot in a soft black-and-white that calls to mind the photographs of Edward Weston, show Aguilar posed in scrubby landscapes, laying in a fetal position surrounded by rocks or reclining by a shallow pool. The figure of her body oscillates between a beautiful, formal abstraction—it almost disappears in some images—and moments of sharp realization that this large, soft form is in fact Aguilar herself. The effect is more dramatized in the Grounded series (2006-07), in which Aguilar is shown near natural formations that mirror the shape of her body. In various images, the folds in her back and sides mimic the gentle contours of a boulder; the crack between her buttocks picks up again in the crack in a large monolith; the wandering line of her arm and breast follows that of an exposed tree root.

In these works, Aguilar explores a meaningful connection between her body and the earth through direct, material engagements, whose complexity exceeds their conventional framing as expressions of self-acceptance in nature. Through her small, photographed gestures, Aguilar opened her work to broader questions about the inextricability of human reference and the land; the feminization of nature in environmental politics; migration through landscapes exactly such as those in her images; the indigenous histories potentially buried in or erased from these sites. The works connect with a long history of feminist earth art – from Nancy Holt mired in reeds with her camera in Swamp (1969) to Beverly Buchanan’s earthen mounds built at sites of racial atrocities in the American South (1979-81) to Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas (1973-80) – in which female artists have used their bodies to document the land and unearth its embedded histories and ideologies. The works also dialogue with a more recent trajectory of Latin American performance art, wherein artists like Regina José Galindo(See the workTierra (2013).) and Ernesto Pujol(See the work Inheriting Salt (2008).) have positioned their vulnerable nude bodies in rural sites to open broad conversations about migration, extraction, and colonialism.(The latent performativity of Aguilar’s landscape nudes is unleashed by the last work in the exhibition, Untouched Landscape (2007), a video shot in front of a desert outcropping in which Aguilar, for one final time, presents and discusses her body for the viewers as the deadpan camera pans slowly up and down her body.)

Concerns of belonging and biography were unavoidably the central subject of Aguilar’s work, and in a political moment such as the present, it could be argued that giving a platform to an artist such as Aguilar is a radical gesture itself. But as claims of diversity are used more and more to gloss over the artworld’s structural failures, questions of representation cannot be the only ones asked of artists and their work. What does it mean to laud the deep influence of Aguilar’s work without discussing its equal parts loving and conflictual relationship with the canon? How do we (myself included) posthumously celebrate an artist while acknowledging the severity of her institutional exclusion during her lifetime? Even if she unquestionably “disrupt[ed] normative concepts of beauty and the female form,” is that the most interesting thing we can say about her work? In the face of targeted attacks on non-white, non-normative identity groups, we need to hold space for artists from marginalized communities wherein their work can be nuanced, historicized, difficult, and perhaps even left unresolved— in other words, to be in the world as art. Show and Tell is a broad, loving presentation of Aguilar’s work, but let us hope it is just the beginning of the conversation.