Art and/as Radical Labor: We Wanted a Revolution at the Brooklyn Museum

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85 at the Brooklyn Museum, April 21 – September 17, 2017.

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.

—Audre Lorde, “Poetry is not a Luxury,” 1985

Before you enter the first exhibition gallery of the Brooklyn Museum’s We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85, the title communicates an internal contradiction. The action and hope expressed by its signal words—“revolution” and “radical”—is complicated, perhaps even negated by the past tense of “wanted,” which turns the urgency of the declaration into a doleful complaint of a promise thwarted. It’s a fitting introduction to an exhibition that assembles a group of black women artists who embraced near-utopian ideals at the same time that they were fully immersed in the logistics of organizing against (and surviving) racism and sexism. At its core, We Wanted a Revolution poses a compelling, unanswered question: can an exhibition effectively lodge a critique of structural exclusion in a context produced and defined by said exclusion?

Before you enter the first exhibition gallery of the Brooklyn Museum’s We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85, the title communicates an internal contradiction. The action and hope expressed by its signal words—“revolution” and “radical”—is complicated, perhaps even negated by the past tense of “wanted,” which turns the urgency of the declaration into a doleful complaint of a promise thwarted. It’s a fitting introduction to an exhibition that assembles a group of black women artists who embraced near-utopian ideals at the same time that they were fully immersed in the logistics of organizing against (and surviving) racism and sexism. At its core, We Wanted a Revolution poses a compelling, unanswered question: can an exhibition effectively lodge a critique of structural exclusion in a context produced and defined by said exclusion?

Organized by Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley, the dense exhibition is a chapter in the unfolding “Year of Yes” programming organized by the Brooklyn Museum’s Sackler Center for Feminist Art in celebration of its tenth anniversary. The program has featured white feminist icons of various generations, including Georgia O’Keeffe and Marilyn Minter, in and around the museum’s heralded collection of Feminist Art, which is anchored by Judy Chicago’s monument to cisgender white womanhood, The Dinner Party (1974-79). (It should be noted that a subtle monographic exhibition of African American sculptor Beverly Buchanan preceded this show.) We Wanted a Revolution acknowledges its context and stakes out a distinct territory for its assembled artists, noting in an introductory wall text that many of them did not identify with the term “feminism” because it connoted a white women’s struggle that ignored the concerns of women of color. In doing so, the curators challenge an implicitly white, bourgeois, and heteronormative definition of feminist art. Nonetheless, the exhibition’s temporal framing begins with the ascendance of Second Wave Feminism in the 1960s and concludes with the emergence of new forms of political identification on the verge of the 1990s.

In an apparent first for Sackler Center programming, We Wanted a Revolution spills into the contemporary galleries normally reserved for its permanent collection. Beyond the obvious symbolism, the spatial reorganization accommodates an expansive five sections organized around key “movements, collectives, actions, and communities.” Dense with artworks and ephemera, these pedagogical units leverage the institution’s resources toward a project of knowledge production.

The exhibition is an act of care, the cumulative result of conservation, archiving, archival research, and even the extraction of a few long-undisplayed artworks from storage. It marks an opportunity to figure care not as marginal, feminized, and domestic, but rather as resistant, perhaps radical labor—a politics many of the featured artists embodied. Moreover, by occupying the galleries that overlook the central beaux-arts court and but up against collections of American furniture and period rooms, We Wanted a Revolution encourages visitors to reflect on the history of American art that is manifested by the Museum’s architecture—a timeworn narrative of progress from early settler colonialism to present-day multiculturalism. Whether the exhibition should be read against or as a corrective part of this history is a question left unresolved.

With its structure driven by key organizations and exhibitions—like Spiral, the short-lived and largely forgotten African-American collective founded in New York in 1963—the project makes a compelling argument that the creative labor of its assembled artists should be viewed as inseparable from the politics, community organizing, and administration that facilitated its production and display. In this way We Wanted a Revolution is resolutely feminist, refusing the traditional divide between cultural life and domestic life that has been used to marginalize women. Spiral marks a fitting if exceptionally complicated introduction to the show, however, since the organization accepted only one woman to its ranks: the painter Emma Amos. In her vibrantly colored, subtly narrative paintings, intimate visions of women in domestic spaces give visual form to the double bind that many black female artists might have found themselves in at the time: isolated by racist and sexist exclusion into a realm deemed incommensurate with legitimate artmaking. They draw a stark contrast with bombast of the more immediately recognizable posters and prints made around the same time by Barbara Jones-Hogu, Samella Lewis, and Elizabeth Catlett, which recruited to new forms of sociality and, in the process, established a visual idiom for the nascent Black Arts Movement, replete with Africana and images of civil rights heroes like Malcolm X and Rosa Parks.

Cases of archival material abound with newspaper clippings, correspondence, and meeting agendas that could easily pertain to recent events. A 1979 open letter addressed to Artists Space indicts the downtown Manhattan organization’s decision to exhibit a series by a white artist called The N***** Drawings; a flyer calls for artists and artworkers to unite in protest of the racist practices of the staff and to help Artists Space “become a true alternative space.” While some visitors may read these as relics of a racist past, the questions of the limits of white empathy and the ownership of black history and trauma remain as unresolved today as they did in the 1960s, in the art sphere and of course the world at large. Hannah Black—the same artist and critic who called on the Whitney Museum to remove and destroy the white artist Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till’s dead body from its 2017 biennial—has argued that this exhibition “reflects the tragedy of the canonization of political art, in the sense that this art once worked toward the horizon of a different way of life entirely.” A way of life that never came to be, as implied by the past tense of the title’s “wanted.”

This “tragedy” bears out, for certain, in much of the work and archival material presented in We Wanted a Revolution, which the Brooklyn Museum has the privilege to display in a gesture of self-criticality that positions itself as rewriting the problematic canon—andthus, perhaps, counter to its fellow New York institutions who have yet to grapple as explicitly with their role in this history.(The flagship institution of the city’s most out of control real estate market, the Brooklyn Museum in fact finds itself at the heart of debates around gentrification and its explicit racial politics. In 2015, it played host to a real estate summit, then an anti-gentrification summit the year after in response to public outcry.) In one of the numerous, densely filled cases, a broadsheet from a 1971 “open hearing” at the Museum is exhibited, summarizing a forum addressing the question, “are museums relevant to women?” that ultimately decided, “no.” Another section reassembles Ana Mendieta’s important 1980 AIR Gallery exhibition Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States, in which the Cuban-American artist brought together figures like Buchanan, Senga Nengudi, and Howardena Pindell to offer an explicit critique of what she called “mainstream feminism” as an exclusively white movement—one for which the Brooklyn Museum has been a traditional home. But these artists are all better known and more exhibitable now. Mendieta renounced AIR a few years after the show, and then she fell to her death in 1985.

With their earnest intensity, many of these objects still burn in the present moment. Elizabeth Catlett’s arresting Target (1970) is a bronze head of a black man in the crosshairs of an implied gun, made in response to the police killings of Black Panther Party members Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in 1969. Originally done for the women’s prison at Rikers Island, Faith Ringgold’s enormous painting For the Women’s House (1971) offers a utopian vision of white and black women performing routine jobs in simple harmony; rendered in Ringgold’s signature free-form cubism, the brightly colored figures vibrate intensely. Betye Saar’s more cynical Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail (1973) is a Molotov cocktail with a hand-drawn image of a mammy figure on the label. It appears grimy and worn, adding a degree of realism to its implied past use as a weapon of protest. The latent energy of these objects has no doubt been blunted by time and institutional re-presentation, but it is still present.

Although this work belongs to a period in which identity politics relied on more recognizable tropes and forms of identification, many of the artists exhibit an understanding of identity that was more nuanced than the dialogue typical of the time allowed for. Since the 1960s, the terms of identity have shifted away from essentialist categories and towards an understanding of identity as performative and intersectional, which often hews to norms and social constructs but, by its very definition, can also deviate. Inkling notions of performativity emerge in many of the works towards the end of the exhibition’s time span, giving visual form to an (almost poststructuralist) understanding of identification and subjectivity that wouldn’t be articulated by the likes of Judith Butler and Stuart Hall for some years. Centering the body as both the agent of identity performance and as the nexus of resistance to white patriarchal domination, these artists made work that continues to exceed its structural contexts and resist easy recuperation into institutional narratives.

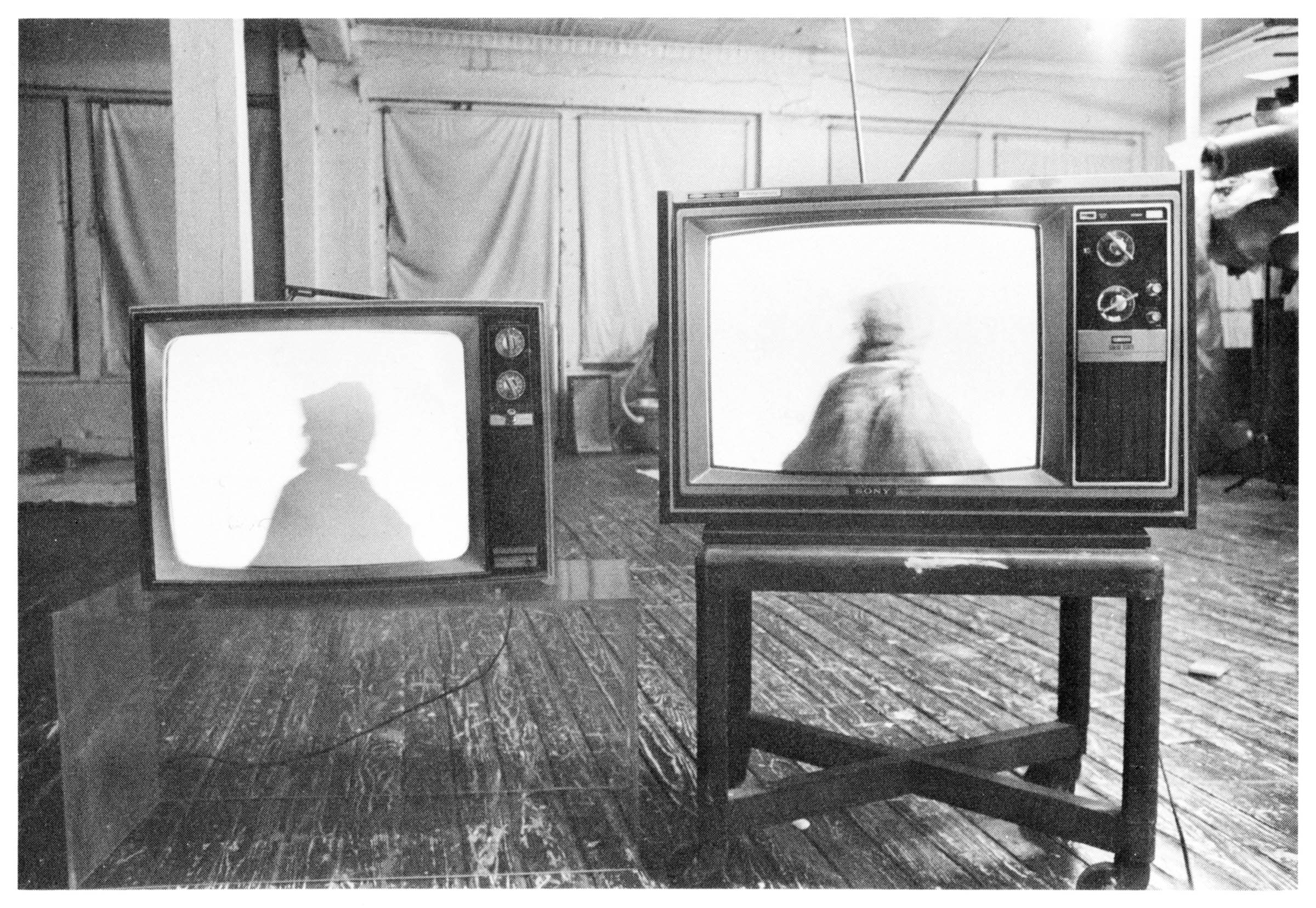

Most of these transient moments are facilitated by the moving image, perhaps thanks to its ability to smuggle rawness and irresolution into a gallery context more handily than traditional media. Howardena Pindell’s Free, White and 21 (1980) is a twelve-minute video that was first exhibited in Mendieta’s aforementioned AIR show. In an apparent departure from her better-known compositions of meticulously collaged paper, the video centers a young Pindell recounting numerous stories of the casual racism she experienced as a girl in Ohio and a struggling artist in New York. One incident involved her white babysitter trying to bleach her skin; in another, the hostess of a bridal luncheon in Kennebunkport, Maine went out of her way to make sure Pindell’s hand would be the last she shook. Delivered in a devastating deadpan, these stories are interspersed with vignettes in which Pindell plays a “white” woman—her face made up with grotesque makeup—who admonishes the real Pindell that her memories of these experiences are mere paranoia. “Don’t worry, we’ll find other tokens,” the antagonist says at one point; in others, she wraps her head in white toilet paper, or peels off a sticky, milky mask from her face and holds it up to the light. Switching in between these characters, referencing masking and unmasking, Pindell demonstrates an understanding of racism and racial identity as dual performances that are made manifest in, vie for control of, and can be resisted by the very same body.

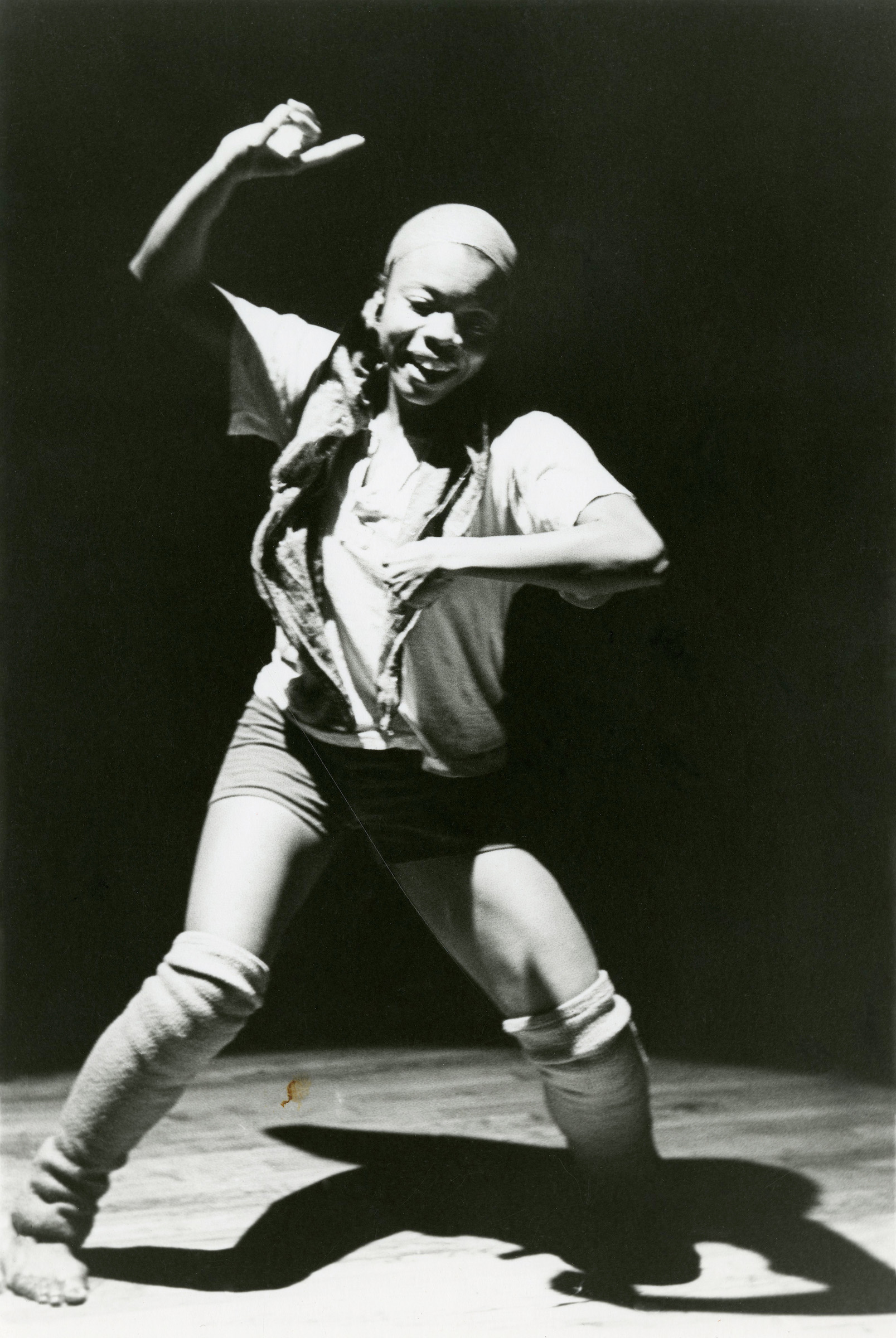

In a similar vein, Blondell Cummings’ 1981 dance performance Chicken Soup is in the exhibition by way of video documentation. The absorbing solo performance spotlights an energetic Cummings alone on a stage, loosely pantomiming the preparation of the titular soup but interspersed with movements both mundane and virtuoso, abstract and referential. She mimes a song to herself, has a mouthed conversation with her invisible ingredients, before launching into passages of frenetic leaps, full-body shimmies, and deep bows. What starts as the motion of scrubbing the floor quickly escalates into a sliding, circling feat of strength. A few years after Yvonne Rainer and the Judson School had insisted there was no split between everyday movement and artistic dance, Cummings mobilizes their performance strategies toward more overtly political aims. With her mix of graceful and jerky movements on the stage, she makes visible the performative artistry of women’s labor, collapsing the public and domestic spheres in her dancing, resisting body.

In a similar vein, Blondell Cummings’ 1981 dance performance Chicken Soup is in the exhibition by way of video documentation. The absorbing solo performance spotlights an energetic Cummings alone on a stage, loosely pantomiming the preparation of the titular soup but interspersed with movements both mundane and virtuoso, abstract and referential. She mimes a song to herself, has a mouthed conversation with her invisible ingredients, before launching into passages of frenetic leaps, full-body shimmies, and deep bows. What starts as the motion of scrubbing the floor quickly escalates into a sliding, circling feat of strength. A few years after Yvonne Rainer and the Judson School had insisted there was no split between everyday movement and artistic dance, Cummings mobilizes their performance strategies toward more overtly political aims. With her mix of graceful and jerky movements on the stage, she makes visible the performative artistry of women’s labor, collapsing the public and domestic spheres in her dancing, resisting body.

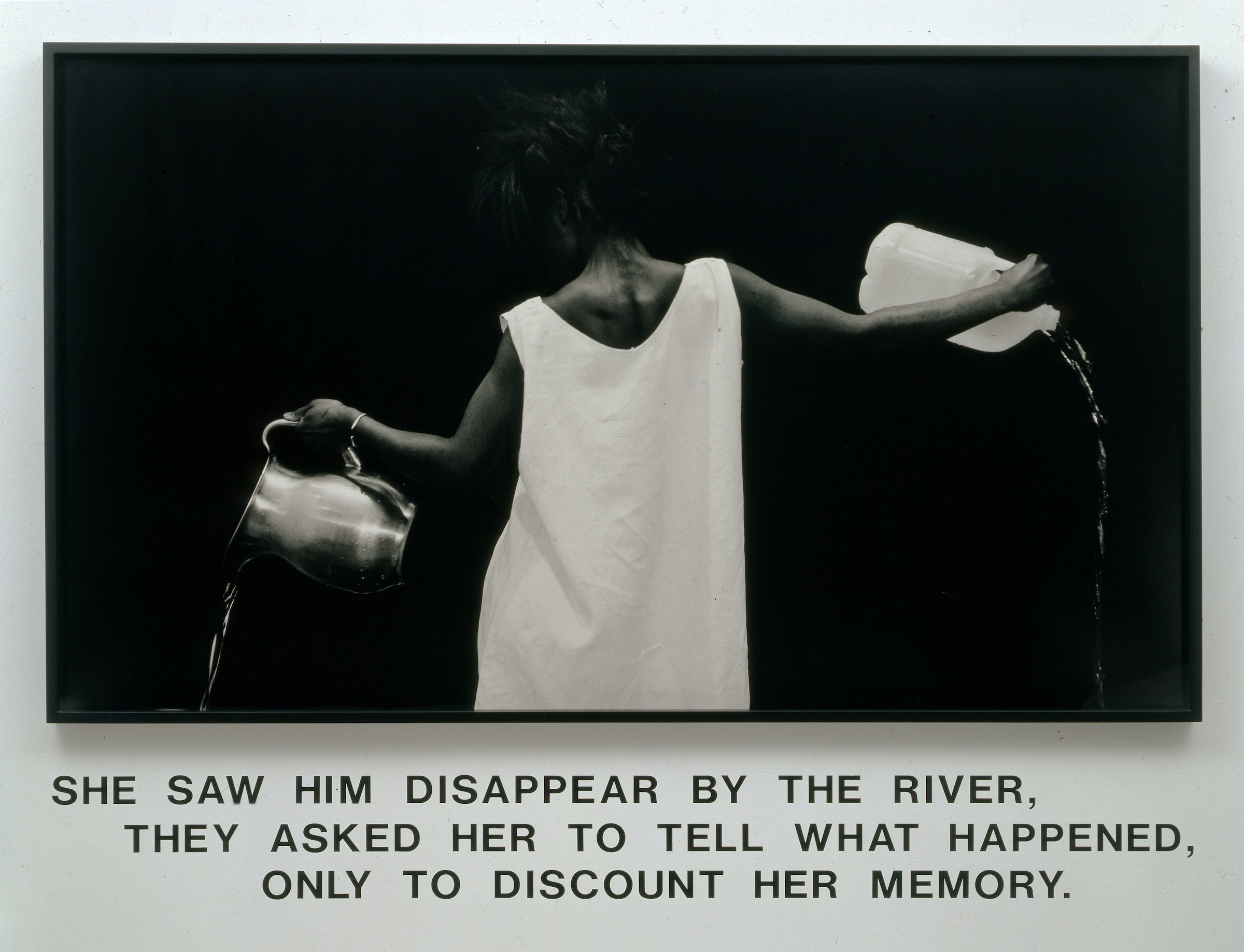

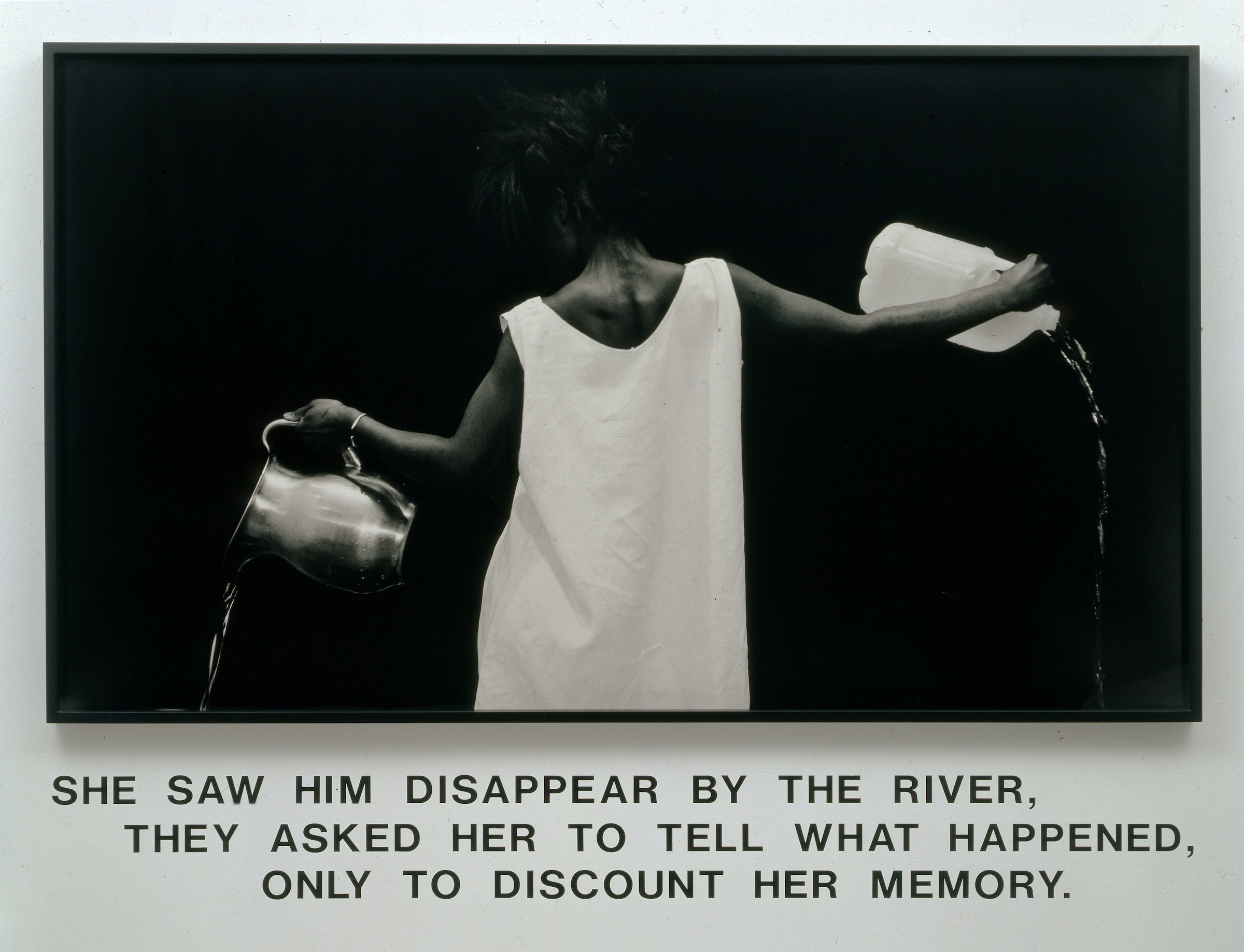

Strands of performativity find their way less literally into other parts of We Wanted a Revolution as well. Senga Nengudi’s ongoing engagement with stockings and other fabrics indexical to women’s bodies slides freely between performance, sculpture, and photography, as in the haunting performance object Inside/Outside (1977) or the documentation of Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978), a collaborative happening Nengudi staged under an overpass in Los Angeles that made use of her nylon creations. Elsewhere, Buchanan’s small, understated sculptural fragments draw on the legacy of Minimalism to activate the spaces around them with processes of memory and critique. Photographs by Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems—the latest works in the show—reveal an understanding of representation as foundational to identity, and the body performing before the camera as a means of interrogating this relationship.

Taken as a whole, the trajectory mapped out by We Wanted a Revolution suggests that in the two decades it tracks, the multivalent group of variously associated black women artists became more and more keenly attuned to the strategies by which their work might eventually be institutionalized. Ways of understanding identity that countered hegemonic formulations were developed in tandem with forms of artmaking and organizing that resisted the art institution. Some chose to play a game whose rules had already been set, rightfully predicting their work might find a home in the canon and its strongholds. Others embraced slippery irresolution in their practices, centering performing bodies or the suggestion thereof that would forever exceed the circumstances of their display and resist pat historicization. We Wanted a Revolution’s great achievement is having made space for all these strategies to coexist in complex disharmony, resisting the singular narratives of Black Art and Feminist Art that have become the calling card for institutions wanting to seem progressive but ultimately act safely.

As Lorde wrote in her defiant essay “Poetry is not a Luxury” in 1985, the final year of the exhibition’s scope, black women’s creative practices are not and never have been a luxury, nor are they ever, in any form, neutral or separable from the conditions of life that make them possible. Some thirty years later, We Wanted a Revolution asks us—whether consciously or not—how far we have come, or if the old forms of artmaking and activism are as needed today as they were then.