Dreams & Drama. Law As Literature

Dreams&Dramas. Law as Literature at neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK), Berlin, March 10 – May 7, 2017

The exhibition Dreams&Dramas. Law as Literature at neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK) in Berlin is the most recent in a spate of exhibitions and symposia to address law through art in the last five years. In 2013, the Persona Ficta exhibition at Bard Center for Curatorial Studies presented “formal spaces of law as vehicles for poetic political action,”(Persona Ficta, Bard CCS, 2013 http://www.bard.edu/ccs/persona-ficta/ (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) and Imagine the Law at FKSE Stúdió Galéria in Budapest (2013) sought to “identify positions in which art can actively be influencing, challenging and reshaping our legal and economic systems.(Imagine the Law, FKSE Stúdió Galéria, 2013 http://studio.c3.hu/en/arch/imagine-the-law/ (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) The symposium, Art, Life, and the Rule of Law, at Lund University in Sweden in 2014 dealt with art and biopolitics,(Art Life and the Rule of Law Symposium, Lund University–Department of Art and Cultural Sciences, 2014 http://www.aidel.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/2014_LUND-programma.pdf (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) while the Law as Raw Material module of the Counterhegemony: Art in a Social Context program at Contemporary Art Center Vilnius approached law as genealogy.(Counterhegemony: Art in a Social Context, Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius, 2014 http://www.artandeducation.net/announcements/107432/call-for-applications-counterhegemony-art-in-a-social-context-artist-fellowship-program (Retrieved July 30, 2017); Law as Raw Material, Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius, 2014 http://nidacolony.lt/en/residence/curated-residencies/counterhegemony-art-in-a-social-context/module-2-law-as-raw-material (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) The Legal Medium: New Encounters of Art and Law symposium hosted by the Yale Journal of Law and Humanities in 2015 (The Legal Medium, Yale University, 2015 http://www.thelegalmedium.com/speakers/ (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) and accompanying exhibition Irregular Rendition “examine[d] processes of ‘naturalization.’”(Irregular Rendition, Giampietro Gallery, 2015 http://www.thelegalmedium.com/exhibition/ (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) And in March of this year, an entire biennial in Belgium, Countour Bienniale, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium explored “justice itself …a ‘medium’ that is simultaneously a performative, ethical and aesthetic operation.”(Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, Contour Biennial in Belgium, 2017 http://contour8.be/en/public-programme (Retrieved July 30, 2017).)

One observable trend in the exhibitions and programs on art and law organized in the U.S. is a quintessentially American preoccupation with lawsuits and the defense or contestation of individual property rights (for example, superstar cases like artist Richard Prince being sued for his unauthorized appropriation of a photographer’s work), whereas exhibitions in Europe tend to approach law through a more counterhegemonic or all-encompassing lens. Dreams&Dramas, with Polish curator Agnieszka Kilian, Polish artist Alicja Rogalska, and Czech artist Jaro Varga spearheading the curatorial team, is a tour-de-force that grapples with the fact that law is an intangible, mental construct that has very tangible, material ramifications. Covering a panoramically vast and eclectic scope of issues – from the French Napoleonic Code to border disputes between Romania and Ukraine to an African-American woman in the 1950s who had her cells extracted during cancer treatment only to have these cells posthumously declared “immortal” by the hospital – the exhibition included sixteen artists hailing from France, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, Mexico, Austria, Brazil, India and the U.S. Perhaps because nGbK curator Kilian was a practicing lawyer for ten years, this exhibition avoided the superficial fetishization and aestheticization of legal documents of previous art and law exhibitions and, instead, delved into the nuances of how law produces our reality, our personhood, our citizenship, and even bodies in public space.

One observable trend in the exhibitions and programs on art and law organized in the U.S. is a quintessentially American preoccupation with lawsuits and the defense or contestation of individual property rights (for example, superstar cases like artist Richard Prince being sued for his unauthorized appropriation of a photographer’s work), whereas exhibitions in Europe tend to approach law through a more counterhegemonic or all-encompassing lens. Dreams&Dramas, with Polish curator Agnieszka Kilian, Polish artist Alicja Rogalska, and Czech artist Jaro Varga spearheading the curatorial team, is a tour-de-force that grapples with the fact that law is an intangible, mental construct that has very tangible, material ramifications. Covering a panoramically vast and eclectic scope of issues – from the French Napoleonic Code to border disputes between Romania and Ukraine to an African-American woman in the 1950s who had her cells extracted during cancer treatment only to have these cells posthumously declared “immortal” by the hospital – the exhibition included sixteen artists hailing from France, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, Mexico, Austria, Brazil, India and the U.S. Perhaps because nGbK curator Kilian was a practicing lawyer for ten years, this exhibition avoided the superficial fetishization and aestheticization of legal documents of previous art and law exhibitions and, instead, delved into the nuances of how law produces our reality, our personhood, our citizenship, and even bodies in public space.

The question “What is a legal fiction?” is intimated but never explicitly asked in the beginning of Rogalska’s twelve-minute video, What If As If (2017). Three separate people each present an answer: “Law is like a balloon—the fiction is that if you blow some air and make the balloon bigger, you make the application of the law bigger.” “An assumption in order to get a result that seems more logical and fair than if you did not have that fiction.” “If you have a really straight line, and then you have to break the line and add a piece, because the line is not always perfect.” Next we witness five people (from Colombia, Germany, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, and Syria) seated in a circle. They seem to be brainstorming, weaving together a verbal patchwork of allegory, speculation and metaphor regarding the notion of “legal fiction,” a narrative technique in law through which it shapes reality. The video is intriguing in its use of ellipsis: again it never asks the question explicitly to the five, who we later learn are migrant-lawyers. Instead, it leaves us with fragments of truncated discussions about the border as a legal fiction, or the arbitrary legality of dividing Pakistan and India in two countries in 1947, or tinkering with the definitions of fiction, reality and abstract vis à vis immigration law. The video’s green screen—a post-production technique that blocks the background of a subject in a video in order to overlay a different background—reverberates with allusions to the disassembling, reconstructing, and inserting of a legal fiction, as the five concoct fictional legal scenarios that would permit them to stay in the U.K.

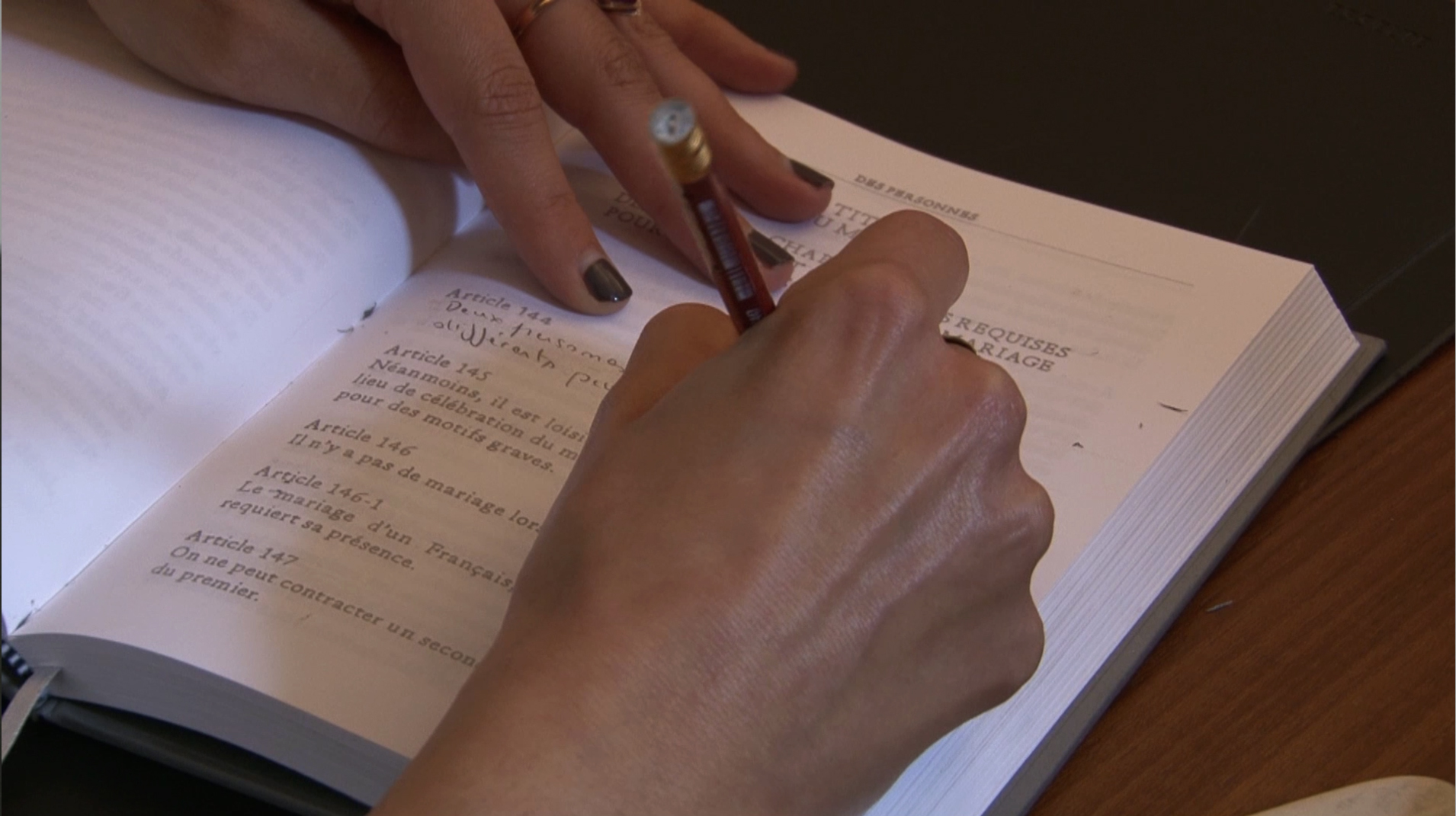

Mexican-born artist Carlos Amorales deals with the issue of erasure in his video Supprimer, Modifier et Préserver (2012). Erasure in visual art has a long pedigree, from Robert Rauschenberg’s reknowned Erased Willem de Kooning, in which he asked de Kooning for a drawing of his that he could erase; to Joseph Kosuth’s Zero and Not, based on erasing or crossing out Freud’s text; to Ad Reinhardt’s black monochrome paintings about which Kosuth said: “Painting itself had to be erased, eclipsed, painted out in order to make art.”(Keith F. Davis, “Affinities…Now and Then”, February 1, 2013, p. 3. http://kcai.edu/sites/default/files/Affinities%20Now%20and%20Then-Brochure%20Scan.pdf (Retrieved July 10, 2017).) Amorales printed out the French Civil Code (also known as the Napoleonic Code, established in 1804) in graphite and in book form, and met individually with the eight lawyers, asking them which part of theFrench law they think should or could be erased. Not merely a formalist exercise of erasing to make a pretty art piece, his engagement with erasure confronts head on the shortcomings, loopholes, contradictions, and deceits of the French legal system. This piece was also not a blatant act of negation. The lawyers grapple with the idea of what it means to erase and if it is even feasible, with one lawyer saying she did not think any part of the law could be solely erased, only erased then replaced. One lawyer states that the French Civil Code is meaningless by itself unless interpreted within a context— therefore, the erasure of the already meaningless code would constitute a redundancy. Like Rogalska’s video, the interactions in this video teeter between being discursive, factual, philosophical, and performative in a way that is extremely satisfying. Amorales’ video is not a dry documentary with a sterile presentation of facts nor is it a performance dwelling in imaginative fantasy unmoored from any social reality; instead, it is a carefully calibrated hybrid of the two.

Mexican-born artist Carlos Amorales deals with the issue of erasure in his video Supprimer, Modifier et Préserver (2012). Erasure in visual art has a long pedigree, from Robert Rauschenberg’s reknowned Erased Willem de Kooning, in which he asked de Kooning for a drawing of his that he could erase; to Joseph Kosuth’s Zero and Not, based on erasing or crossing out Freud’s text; to Ad Reinhardt’s black monochrome paintings about which Kosuth said: “Painting itself had to be erased, eclipsed, painted out in order to make art.”(Keith F. Davis, “Affinities…Now and Then”, February 1, 2013, p. 3. http://kcai.edu/sites/default/files/Affinities%20Now%20and%20Then-Brochure%20Scan.pdf (Retrieved July 10, 2017).) Amorales printed out the French Civil Code (also known as the Napoleonic Code, established in 1804) in graphite and in book form, and met individually with the eight lawyers, asking them which part of theFrench law they think should or could be erased. Not merely a formalist exercise of erasing to make a pretty art piece, his engagement with erasure confronts head on the shortcomings, loopholes, contradictions, and deceits of the French legal system. This piece was also not a blatant act of negation. The lawyers grapple with the idea of what it means to erase and if it is even feasible, with one lawyer saying she did not think any part of the law could be solely erased, only erased then replaced. One lawyer states that the French Civil Code is meaningless by itself unless interpreted within a context— therefore, the erasure of the already meaningless code would constitute a redundancy. Like Rogalska’s video, the interactions in this video teeter between being discursive, factual, philosophical, and performative in a way that is extremely satisfying. Amorales’ video is not a dry documentary with a sterile presentation of facts nor is it a performance dwelling in imaginative fantasy unmoored from any social reality; instead, it is a carefully calibrated hybrid of the two.

Having attended many of the art and law exhibitions and symposiums mentioned above, I have come to expect certain recurring motifs. Usually one encounters some variant of the “art is going to fix what is wrong, corrupt, or indefensible in law or society” or “art is a sphere that is ethically superior to law.” On the face of it, this could be a supremely naive, if not a self-aggrandizing supposition, marked by a lack of self-awareness of art’s utter inconsequentiality on the geopolitical stage. However, this impulse finds its most poignant and incisive instantiation in Patrick Bernier and Olive Martin’s well-known performance X and Y v. FRANCE: The Case for a Legal Precedent (2007-2017), re-performed and presented as a video at nGbK, without which no art and law exhibition would be complete. French artists Bernier and Martin noticed the searing irony of the rapid expansion of copyright and intellectual property law in the digital era in France, juxtaposed next to the “diminishing rights and freedom of movement of immigrants under French and EU law.”(Audrey Chan, “Artists at Work: Patrick Bernier and Olive Martin,” Afterall, March 11, 2009, https://www.afterall.org/online/bernier-martin.essay#.WT5igvnF-So (Retrieved July 10, 2017).) Bernier asked a gallery in London who had offered him a solo exhibition if he could declare an undocumented immigrant facing deportation in France as the author of a work and, thereby, allow the immigrant to circumvent deportation from France. When the gallery refused, they created a performance of the two lawyers actually arguing the case of the immigrant, rendering “undocumented people” the subject of intellectual property. Paradoxically, it is only through the act of legal objectification of the immigrant do they find a means by which to restore his subjectivity. That is to say, by rendering the immigrant a named entity or “object” in this law’s stipulation, they hope to restore him as a legitimate subject in the eye of the law (which now only sees him as “illegal immigrant”).

Another trait I have come to expect from art and law exhibitions is the reams of dry featureless binders of legal documents on display, alluded to in Benjamin Buchloh’s seminal essay, “Conceptual Art 1962-1968: From the Aesthetics of Administration to the Critique of Institutions.” Here he delineates how conceptual art at its outset aspired to a rigorous elimination of visuality, representation, craft, claims of transcendence, and other criteria of traditional aesthetics.(Benjamin Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962-1968: From the Aesthetics of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” October, Volume 55, Winter 1990, pp. 105-43.) Instead, it proposed art as a linguistic proposition within an unadorned aestheticof administrative and legal organization. In his essay, Buchloh addresses Sol LeWitt’s commentary on the “art as information” tendency: “The aim of the artist would be to give viewers information…He would follow his predetermined premise to its conclusion avoiding subjectivity. Chance, taste or unconsciously remembered forms would play no part in the outcome. The serial artist does not attempt to produce a beautiful or mysterious object but functions merely as a clerk cataloguing the results of his premise”.(Sol LeWitt, “Serial Project #1, 1966,” Aspen Magazine, nos. 5-6, ed. Brian O’Doherty, 1967, p. 17.)

Based on Buchloh’s idea, one might claim that what has emerged in these exhibitions is an “aesthetics of administration”— art as unadorned, oftentimes bureaucratic information. The nGbK exhibition did not fall to this fate. Rather, the exhibition exemplified a wily balance between the lyrical/subjective/imaginative, versus the nakedly factual. For instance, in the Amorales’ video, the interviews of the lawyers were interspersed with scenes of the interviewer reading aloud sections of French law on busy city street corners to oblivious passerby. These vignettes could have easily been contrived or pretentious, but Amorales has both a filmmaker’s eye and a filmmaker’s subjectivity that rendered these scenes poetically evocative (at times reminiscent of nouvelle vague films of Godard/Truffaut in their brief spurts of impressionistic absurdity).

Based on Buchloh’s idea, one might claim that what has emerged in these exhibitions is an “aesthetics of administration”— art as unadorned, oftentimes bureaucratic information. The nGbK exhibition did not fall to this fate. Rather, the exhibition exemplified a wily balance between the lyrical/subjective/imaginative, versus the nakedly factual. For instance, in the Amorales’ video, the interviews of the lawyers were interspersed with scenes of the interviewer reading aloud sections of French law on busy city street corners to oblivious passerby. These vignettes could have easily been contrived or pretentious, but Amorales has both a filmmaker’s eye and a filmmaker’s subjectivity that rendered these scenes poetically evocative (at times reminiscent of nouvelle vague films of Godard/Truffaut in their brief spurts of impressionistic absurdity).

This was also the case with an intriguing installation by Brazilian-Italian artist Debora Hirsch and collaborator Ilia Filiberti, HeLa (2015). This piece invoked the story of Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman and descendant of slaves in rural Virginia who was diagnosed with cancer in the 1950s. During her treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital—the sole hospital within a 20-mile radius that treated African-Americans at the time—Henrietta’s cells were sampled without her consent. Because her cells could be divided multiple times without dying they were declared “immortal” by the hospital. Later her cells served to culture a line of cells named “HeLa,” now being used for research for cancer, AIDS, and gene mapping, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, and a myriad of other crucial scientific pursuits.(Van Smith, “The Life, Death, and Life after Death of Henrietta Lacks, Unwitting Heroine of Modern Medical Science,” Baltimore City Paper, April 17, 2002, p. 23.) HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned in 1955 and since then, scientists have grown twenty tons of her cells; today, there are almost 11,000 patents using HeLa cells.(Rebecca Kloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Random House: New York City, 2010), p. 2.) Henrietta’s family later asked for compensation for the hospital’s unauthorized extraction of Henrietta’s cells, but never received any. Hirsch and Filiberti’s installation consisted of a two-meter-high glass wall with various drawer-like boxes attached to its sides, containing reams of papers of black-and-white legal documents addressing the question of who has a right to profit from Henrietta’s cells.

A third trait one often finds in the kinds of exhibitions under review here, is the use of criminality—or some type of “artistic intervention” that borders on being illegal or criminal — for artistic purposes. [One example being the 2012 group exhibition With Criminal Energy: Art and Crime in the 21st Century, at Halle 14 in Leipzig, which explicitly addressed the affinities between crime and art.](With Criminal Energy—Art and Crime in the 20th Century, Halle 14, 2012 http://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/cms/en/projekte/bild_und_raum/archiv/mit_krimineller_energie.html (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) There is also the work of Guatemalan artist Anibal Lopez (a.k.a. A-1 53167), who actually mugged someone at gunpoint in Guatemala City and then used the money to fund an exhibition at Contexto Space in Guatamela. Lopez recounted the “robbery as an event” at the exhibition with a poster claiming that the food and alcohol consumed at the art opening was courtesy of his robbery, thereby posing the question to viewers whether they were accomplices to his crime.(Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick, “A Productive Irritant: Parasitical Inhabitations in Contemporary Art,” Fillip, 15, Fall 2011. https://fillip.ca/content/parasitical-inhabitations-in-contemporary-art (Retrieved July 10, 2017).) Another example of an art project that borders on illegality is the work of Dutch artist Jonas Staal, who beginning in 2005 anonymously erected roadside memorial tributes (candles, photos, and teddy bears) to far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders, as if Wilders were dead. These makeshift memorials were interpreted as death threats and eventually prompted Wilders to have Staal arrested in 2005; Staal then gave out invitations to his trial and turned the court case into an art project.

A third trait one often finds in the kinds of exhibitions under review here, is the use of criminality—or some type of “artistic intervention” that borders on being illegal or criminal — for artistic purposes. [One example being the 2012 group exhibition With Criminal Energy: Art and Crime in the 21st Century, at Halle 14 in Leipzig, which explicitly addressed the affinities between crime and art.](With Criminal Energy—Art and Crime in the 20th Century, Halle 14, 2012 http://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/cms/en/projekte/bild_und_raum/archiv/mit_krimineller_energie.html (Retrieved July 30, 2017).) There is also the work of Guatemalan artist Anibal Lopez (a.k.a. A-1 53167), who actually mugged someone at gunpoint in Guatemala City and then used the money to fund an exhibition at Contexto Space in Guatamela. Lopez recounted the “robbery as an event” at the exhibition with a poster claiming that the food and alcohol consumed at the art opening was courtesy of his robbery, thereby posing the question to viewers whether they were accomplices to his crime.(Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick, “A Productive Irritant: Parasitical Inhabitations in Contemporary Art,” Fillip, 15, Fall 2011. https://fillip.ca/content/parasitical-inhabitations-in-contemporary-art (Retrieved July 10, 2017).) Another example of an art project that borders on illegality is the work of Dutch artist Jonas Staal, who beginning in 2005 anonymously erected roadside memorial tributes (candles, photos, and teddy bears) to far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders, as if Wilders were dead. These makeshift memorials were interpreted as death threats and eventually prompted Wilders to have Staal arrested in 2005; Staal then gave out invitations to his trial and turned the court case into an art project.

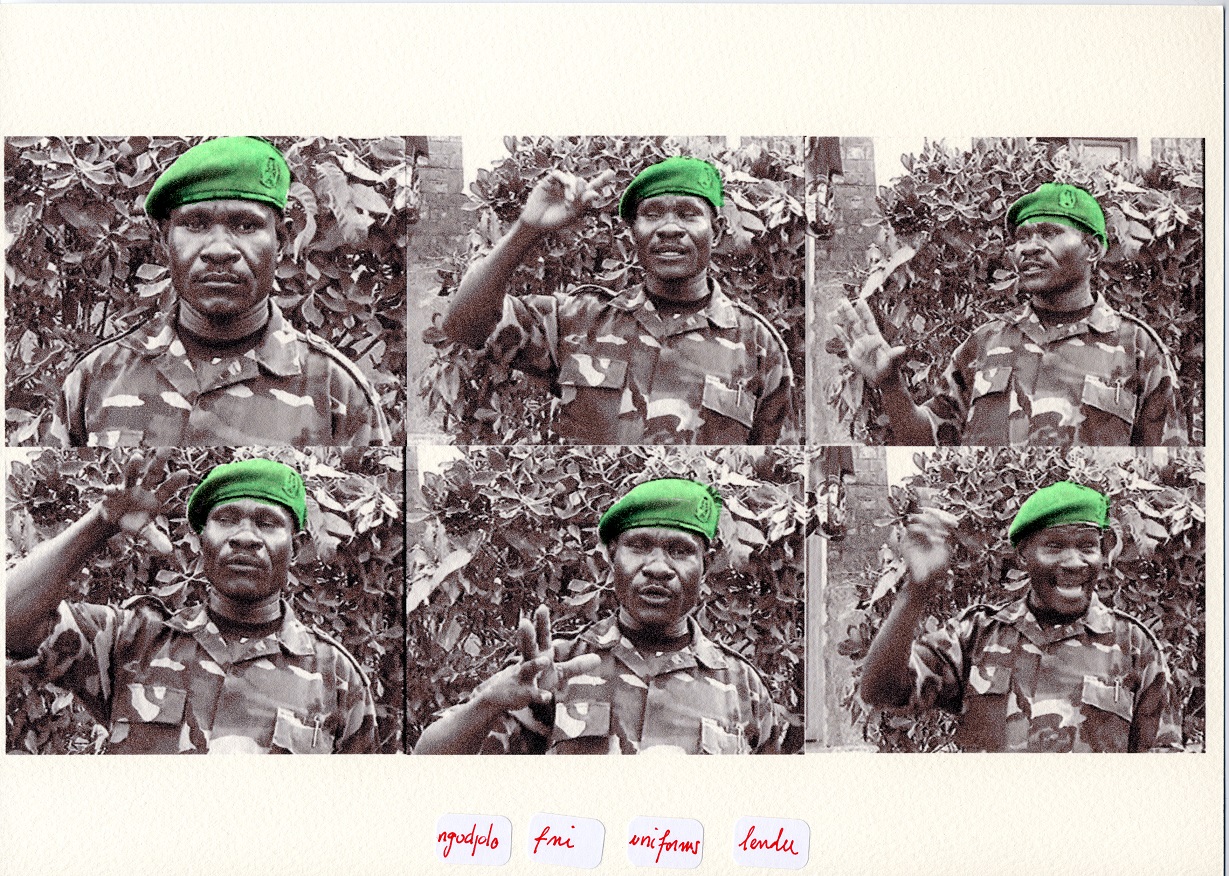

One of the greatest traits of Dreams&Dramas was its complete eschewal of the blockbuster approach more prevalent in American art and law exhibitions where there is a priority to procure celebrities, such as the Yale Art and Law Symposium that invited artists whose work had little or nothing to do with law (for example, Liam Gillick, Kenneth Goldsmith) for the sake of name recognition. Instead, the nGbK exhibition was deeply rooted in an ethnographic approach, selecting pieces that exemplified an airtight-sealed specificity regarding their relation to law. For example, the sprawling and surprisingly interactive installation muzungu (those who go round and round) (2016) by artist franck leibovici and International Criminal Court (ICC) analyst Julien Seroussi, consisted of a half-dozen large panels of ephemera (laminated papers, handwritten letters, stick-it notes, video stills, maps) documenting the 2014 ICC trial of Congolese militants charged with crimes against humanity during the Congolese Civil War.

One of the greatest traits of Dreams&Dramas was its complete eschewal of the blockbuster approach more prevalent in American art and law exhibitions where there is a priority to procure celebrities, such as the Yale Art and Law Symposium that invited artists whose work had little or nothing to do with law (for example, Liam Gillick, Kenneth Goldsmith) for the sake of name recognition. Instead, the nGbK exhibition was deeply rooted in an ethnographic approach, selecting pieces that exemplified an airtight-sealed specificity regarding their relation to law. For example, the sprawling and surprisingly interactive installation muzungu (those who go round and round) (2016) by artist franck leibovici and International Criminal Court (ICC) analyst Julien Seroussi, consisted of a half-dozen large panels of ephemera (laminated papers, handwritten letters, stick-it notes, video stills, maps) documenting the 2014 ICC trial of Congolese militants charged with crimes against humanity during the Congolese Civil War. The piece lays out the “facts of the case,” putting the viewer in the place of the court, as well as its model of proceedings: witness hearings, site inspections, transcripts, document materiality. Through the court testimony viewers are taken through a comprehensive array of vignettes (fragments of decontextualized information) that begin to form the narrative of what happened: the status of the “wisemen” in the village, the Motorola radio used to organize the attack, gruesome scenes of children hacked with machetes, the politics of the word “combatant” in legitimizing different factions of fighters. The piece then invites all viewers to disassemble and reassemble these fragments in new configurations on a separate bulletin board, a testament to the malleability of the “facts of the case.” Like the works by Rogalska and Amorales, this piece provocatively intertwined denotative elements (facts from the trial) and connotative elements that imparted a subjective means by which viewers could perceive “the facts.”

The piece lays out the “facts of the case,” putting the viewer in the place of the court, as well as its model of proceedings: witness hearings, site inspections, transcripts, document materiality. Through the court testimony viewers are taken through a comprehensive array of vignettes (fragments of decontextualized information) that begin to form the narrative of what happened: the status of the “wisemen” in the village, the Motorola radio used to organize the attack, gruesome scenes of children hacked with machetes, the politics of the word “combatant” in legitimizing different factions of fighters. The piece then invites all viewers to disassemble and reassemble these fragments in new configurations on a separate bulletin board, a testament to the malleability of the “facts of the case.” Like the works by Rogalska and Amorales, this piece provocatively intertwined denotative elements (facts from the trial) and connotative elements that imparted a subjective means by which viewers could perceive “the facts.”

Dreams&Dramas was a conceptually, politically, and artistically ambitious exhibition that wholly succeeded, grappling with the performativity of language within a legal context, the subject-object relation within court hearings, and the creation of personhood through the lens of legal strictures. Law was treated almost as a semiotic topography to be variously navigated, uncovered, subverted, elongated, or disseminated. The sheer amount of information one would have to ingest just to process the backstory behind each of the pieces was voluminous, leading to a delightful (and all too uncommon) meaty substantiveness and system overload feeling to the exhibition. Yet despite being rooted in a very specific discursive reality, it was in no way riddled with the austere discursive sterility of some art and law exhibitions. On the contrary, it had a panache for putting together visually evocative and ingeniously creative engagements with highly specific discursive realities.

Dreams&Dramas was a conceptually, politically, and artistically ambitious exhibition that wholly succeeded, grappling with the performativity of language within a legal context, the subject-object relation within court hearings, and the creation of personhood through the lens of legal strictures. Law was treated almost as a semiotic topography to be variously navigated, uncovered, subverted, elongated, or disseminated. The sheer amount of information one would have to ingest just to process the backstory behind each of the pieces was voluminous, leading to a delightful (and all too uncommon) meaty substantiveness and system overload feeling to the exhibition. Yet despite being rooted in a very specific discursive reality, it was in no way riddled with the austere discursive sterility of some art and law exhibitions. On the contrary, it had a panache for putting together visually evocative and ingeniously creative engagements with highly specific discursive realities.