Raša Todosijević in Conversation with Dietmar Unterkofler

Dietmar Unterkofler: You will represent Serbia at this year’s Biennale in Venice, while Tomislav Gotovac will be Croatia’s representative and Marina Abramović will also be there for promoting her Cultural Center in Cetinie (Montenegro). So, three of the key figures of the 1970s avantgarde scene in the former Yugoslavia will be present in Venice. Do you think this is a signal for the late rehabilitation of the still marginalized generation of conceptual artists of the 1970s?

Dietmar Unterkofler: You will represent Serbia at this year’s Biennale in Venice, while Tomislav Gotovac will be Croatia’s representative and Marina Abramović will also be there for promoting her Cultural Center in Cetinie (Montenegro). So, three of the key figures of the 1970s avantgarde scene in the former Yugoslavia will be present in Venice. Do you think this is a signal for the late rehabilitation of the still marginalized generation of conceptual artists of the 1970s?

Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi?: I think we can’t speak of a real rehabilitation, and even if so this is only partly true. I think it is mainly a coincidence that we, as artists of the so called New Artistic Practice are present there at the same time. For Gotovac the reason is, as I see it, the fact that he passed away last year and that his presence will be a kind of life-retrospective. Marina will promote the idea for her cultural centre (the Marina Abramovic Community Centre Obod Cetinje, MACCOC), while the official representatives for Montenegro will be Ilija Šoškic and Natalija Vujoševic.

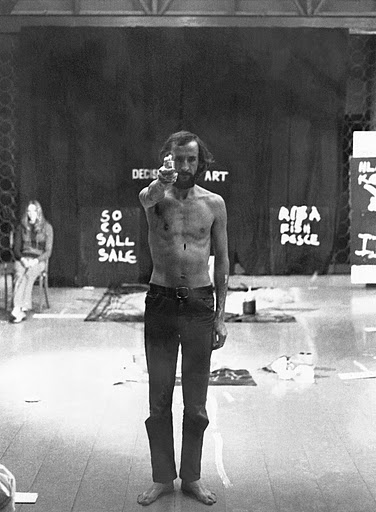

Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi? was born on 2 September 1945, in Belgrade, Serbia. He graduated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, in 1969. He works and lives in Belgrade, Serbia. Todosijevi? is one of the key protagonists of the circle of Belgrade conceptual artists. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he made radical steps away from the ideology and practice of Socialist modernism, taking part in the new movements that were emerging on the world scene. Together with his colleagues (Marina Abramović, Era Milivojevi?, Neša Paripovi?, Zoran Popovi? and Gergelj Urkom) gathering in the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, he contributed to the esrablishment of the so-called New Artistic Practice throughout the territory of former Yugoslavia, and profoundly influenced many contemporary artists. His work is intensely imbued with political and social criticism through the constant questioning and reexamining of traditional cultural and art systems and society as a whole. Todosijevi?’s art practice is directed towards research in various media and techniques, from performance, action, video works and three-dimensional installations to the problematizing of the medium of painting and the practice of painting itself. Todosijevi? has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in prestigious galleries and museums throughout the world. He is the recipient of the ArtsLink 2004 Award; IASPIS Residential Award 2001 (Stockholm); and the 2006 Emily Harvey Foundation Award (New York/Venice). He also received the 50th October Salon Award (Belgrade), as well as the 2009 Politika Award.

Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi? was born on 2 September 1945, in Belgrade, Serbia. He graduated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, in 1969. He works and lives in Belgrade, Serbia. Todosijevi? is one of the key protagonists of the circle of Belgrade conceptual artists. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he made radical steps away from the ideology and practice of Socialist modernism, taking part in the new movements that were emerging on the world scene. Together with his colleagues (Marina Abramović, Era Milivojevi?, Neša Paripovi?, Zoran Popovi? and Gergelj Urkom) gathering in the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, he contributed to the esrablishment of the so-called New Artistic Practice throughout the territory of former Yugoslavia, and profoundly influenced many contemporary artists. His work is intensely imbued with political and social criticism through the constant questioning and reexamining of traditional cultural and art systems and society as a whole. Todosijevi?’s art practice is directed towards research in various media and techniques, from performance, action, video works and three-dimensional installations to the problematizing of the medium of painting and the practice of painting itself. Todosijevi? has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in prestigious galleries and museums throughout the world. He is the recipient of the ArtsLink 2004 Award; IASPIS Residential Award 2001 (Stockholm); and the 2006 Emily Harvey Foundation Award (New York/Venice). He also received the 50th October Salon Award (Belgrade), as well as the 2009 Politika Award.

Dietmar Unterkofler: You will represent Serbia at this year’s Biennale in Venice, while Tomislav Gotovac will be Croatia’s representative and Marina Abramović will also be there for promoting her Cultural Center in Cetinie (Montenegro). So, three of the key figures of the 1970s avantgarde scene in the former Yugoslavia will be present in Venice. Do you think this is a signal for the late rehabilitation of the still marginalized generation of conceptual artists of the 1970s?

Dietmar Unterkofler: You will represent Serbia at this year’s Biennale in Venice, while Tomislav Gotovac will be Croatia’s representative and Marina Abramović will also be there for promoting her Cultural Center in Cetinie (Montenegro). So, three of the key figures of the 1970s avantgarde scene in the former Yugoslavia will be present in Venice. Do you think this is a signal for the late rehabilitation of the still marginalized generation of conceptual artists of the 1970s?

Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi?: I think we can’t speak of a real rehabilitation, and even if so this is only partly true. I think it is mainly a coincidence that we, as artists of the so called New Artistic Practice are present there at the same time. For Gotovac the reason is, as I see it, the fact that he passed away last year and that his presence will be a kind of life-retrospective. Marina will promote the idea for her cultural centre (the Marina Abramovic Community Centre Obod Cetinje, MACCOC), while the official representatives for Montenegro will be Ilija Šoškic and Natalija Vujoševic.

There is surely no new wave of recognition of us on the way, there is a certain contradiction even in my taking part in Venice. A contradiction whose beginnings are to be found thirty years ago, the time when we were young artists working together in the context of the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade.

DU: Why do you think there is a contradiction in this? You are surely on of the best-known Serbian artists on an international scale, and you have had exhibitions in the most important art institutions worldwide.

RT: The cultural situation in this country is not easy and together with the other conceptual artists(Mainly the informal Group of 6 Artists formed by Marina Abramović, Neša Paripovi?, Gergelj Urkom, Era Milivojevi?, Raša Todosijevi? and Zoran Popovi? at the beginning of the 1970s.) around the SKC(The Student Cultural Centre was opened in 1971 as consequence of the students protests in 1969. It offered artists and cultural workers a relatively free space and became the most important place for numerous avantgarde groups in the 1970s.) I have always acted from the margins. This is maybe not true for Marina, but she left the country more than thirty years ago and is now active on a different level. The young people gathering and collaborating within the SKC were actually culturally and economically isolated. But – and now I have to precise about some things – there was also some interest from the institutions, mainly the Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade, in our work and in making us representatives of the then-Yugoslav art.

These were not big events, more like an exchange of activities on a national level, but from time to time we were taking part in international exhibitions as well. And there were many guests from outside visiting Belgrade and taking part in the cultural events at the SKC. Especially the April Meetings for Expanded Media brought artists such as Joseph Beuys, Germano Celant, Barbara Reise and many others to Belgrade. This nonconformist situation was very important for young artists. You didn’t have to apply for organizing exhibitions or screenings, there were always people around you and it was very easy to organize something and talk about art.

But somehow this supposed liberalism was a fraud; its goal was to show the West that there exists a kind of art here that is as modern and progressive as similar tendencies in America, Italy or England. Above all we were all acting in economic isolation, because of course there wasn’t a free art market in socialist Yugoslavia.

DU: The Yugoslav conceptual scene of the 1970s was very active and up do date when it came to international tendencies. Even limiting my search to artist groups from Serbia, I found fifteen different groups that were part of the New Artistic Practice. If we add Slovenia’s OHO group, or the Croatians Goran Trbuljak, Braco Dimitrijevi?, and Mangelos—to name but a few–then this number could be increased by many more. Do you think that, in spite of the mentioned contradictions, those years were better times for making art?

DU: The Yugoslav conceptual scene of the 1970s was very active and up do date when it came to international tendencies. Even limiting my search to artist groups from Serbia, I found fifteen different groups that were part of the New Artistic Practice. If we add Slovenia’s OHO group, or the Croatians Goran Trbuljak, Braco Dimitrijevi?, and Mangelos—to name but a few–then this number could be increased by many more. Do you think that, in spite of the mentioned contradictions, those years were better times for making art?

RT: I wouldn’t say better, and I am already a little tired of repeating the interpretations I have been giving over many years. Although there was a climate of relative liberalism and an innovative and experimental spirit during those years, we were acting at the margins of society and culture. This is true for the SKC in Belgrade as well as for the Youth Centres in Novi Sad, Zagreb and other cities. It was a kind of “game,” a position we could describe as “let the children play.” We were allowed to express ourselves freely as long as the officials were not attacked directly and, above all, as long as we did not criticize Tito directly. Generally speaking, we were not taken seriously. As a parallel phenomenon you have the Black Wave films of those years, with directors such as Želimir Žilnik, Dušan Makavejev, Živojin Pavlovi? and others who were facing very serious problems and repressions, which even took them even to jail or into emigration. This is because the medium film was considered much more serious and dangerous because of its broader distribution and public presence.

Its hard to say if those were better times for art and I do not agree with those mystifications about the 1970s as a golden age for art and freedom, although the times to come, especially the 1990s were certainly terrible times for us artists.

The ruling dogma in the art of the 1970s was still based on the classical disciplines of painting and sculpture. The professors were promoting their old fashioned Paris-style art and it was absolutely impossible for them to open their eyes to the changes that were rolling over the whole art world. Body art, photography, Performance art, Conceptual art, Happening, Fluxus, Neo-dada, Land art, Process Art, Mixed media, and Arte Povera were the artistic practices in which our generation was interested, and these radical changes were marked by real generational clashes between us, our professors, and the so-called dominant establishment. The ideas we were promoting were denounced as “imported from the West” and as not conforming with the socialist ideals our (their) society was supposed to be based on.

DU: Let’s go back to the Biennale.

DU: Let’s go back to the Biennale.

RT: During Yugoslav times we had many biennials here, so we had cultural events taking place here every other year. But there wasn’t any infrastructure for these events, there was no art market, no galleries, neither was there a lot of interest in these biennials outside of the familiar circles. You have to imagine this as if you were building a house in the desert without water, without electricity, without roads. This was only a phantasm or simulacrum of the institution we call biennial.

Nowadays you have numerous biennials or spectacles all over the world, even in Patagonia you have a biennial. These are events taking place on the crossroads between culture, profit, politics, and society. And these events have experienced a real explosion in the last few decades. While the catalogue of the Edinburgh arts festival, in which I used to take part for many years, was a small leaflet in the 1970s, now it is impossible to follow all the happenings going on during the festival.

DU: Based on all this, would you need to expand your Edinburgh Statement on Art from 1975 nowadays?

RT: Absolutely, the whole machinery of the artistic system has become a gigantic spectacle-generating machine.

The Venice Biennale was always interesting for Yugoslavia, and I think also for the other socialist countries, because it was (and still is) based on the principle of the national pavilion. The Documenta in Kassel for example never evoked such interest for the officials in Serbia because it was much harder to show national identity there. The Venice Biennale, even if it presents itself under a common theme or motto, gives opportunities to national (official) participants. In socialist times the artists who were selected to represent Yugoslavia in Venice weren’t chosen so they could develop an international reputation, but–and this is somehow a paradox—so they could establish a position for themselves within their own local artistic tradition. At home this meant a big deal, while the reactions on the international level weren’t crucial. In this context just think about Petar ?ukovi?’s decision to invite Marina Abramović to show her work at the Yugoslavian pavilion back in 1997. The politicians promptly replaced her with Vojo Stani?, a traditional landscape painter who seemed to show authentic local art in a more appropriate manner than one of the world’s most famous performance artists.

DU: On one hand you will be the official representative of your country, and your presence will call for plenty of attention. On the other hand you have been conducting a thorough institutional critique of the local artistic and political scene for the last forty years. How will you deal with this situation?

RT: First of all I am taking part in the Biennale as an individual who represents himself, and not as a state representative. My works are not the result of the collective labour of the whole Serbian nation, but a strongly individualized way of seeing and reacting to my environment. I am 65 years old now and I have to say that, from the point of view of my artistic career, the Biennale call is coming rather late for me. I am not saying this because I have become lazy or too relaxed. I mean it. As an artist and individual, and as citizen of this state, I went through many difficult periods over the last decades, and apart from that I was quite active as an artist and present at many international exhibitions and shows. On the other hand, I am sure that many people from the so- called local culture scene in Serbia are not happy with the decision to send me to Venice. Still, there will probably not be all that much official attention paid to my presence in Venice.

RT: First of all I am taking part in the Biennale as an individual who represents himself, and not as a state representative. My works are not the result of the collective labour of the whole Serbian nation, but a strongly individualized way of seeing and reacting to my environment. I am 65 years old now and I have to say that, from the point of view of my artistic career, the Biennale call is coming rather late for me. I am not saying this because I have become lazy or too relaxed. I mean it. As an artist and individual, and as citizen of this state, I went through many difficult periods over the last decades, and apart from that I was quite active as an artist and present at many international exhibitions and shows. On the other hand, I am sure that many people from the so- called local culture scene in Serbia are not happy with the decision to send me to Venice. Still, there will probably not be all that much official attention paid to my presence in Venice.

I didn’t apply for being selected for the Biennale, I didn’t even think about it until the proposal came from Živko Grozdani?, the director of the Museum for Contemporary Art in Novi Sad. As you know, the institution that is preparing the whole event is the Museum of Contemporary Art in Novi Sad, so that for once, and I really appreciate this, we are bypassing the hegemonic and centralistic position of Belgrade-based art institutions. Instead we focus on a relatively small but all the more productive environment that is outside of the feudal domain of the capital. In order to understand the political dimension of this decision you have to know a little about the national conflicts and the center vs. periphery dynamics in Serbia, and about the way in which it provokes strong conflicts and clashes.

DU: This takes us back to the beginning of our talk: as you can see, certain paradoxes and contradictions that arose in the 1970s are still active in the present.

DU: This takes us back to the beginning of our talk: as you can see, certain paradoxes and contradictions that arose in the 1970s are still active in the present.

RT: I am an old-fashioned artist in the sense that in my work I follow certain ethical principles. During the times of the SKC we were in intense contact with artists all over Europe, even in America. We had contacts with the Vienna Actioniss; with the people from Art&Language around Kosuth; with the Italian Arte Povera scene; and a little later with the “young Wilds” from Germany. It is an interesting fact that Czech artists for example sent their works to us so that that we could send them to Western countries. This was possible because contrary to the countries belonging to the Eastern Block in Yugoslavia we had the freedom to travel. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and of course because of the Yugoslav wars during the 1990s these international contacts came to an end. Those were years of complete isolation and there were also cultural sanctions imposed on Serbia that made it impossible to keep up contacts on a global scale. At the end of the 1990 there was once again some interest in the art scene of our region. Especially in Austria they had many shows, such as Aspects/Positions – 50 years of Art in Central Europe (1999), Blood&Honey-Future’s in the Balkans (2003), or After the Wall – Art And Culture In Post-Communist Europe (1999). This showed a certain interest, perhaps an exotic one, in what was going on here, but without any serious analysis of this cultural and geographical space.

DU:The motto of this year’s Biennale is Illuminations, and the title of your show will be Light and Darkness of Symbols. Will you prepare and perform works that respond directly to this motto? In what way do you see your artistic work correspond to this motto?

RT: I won’t prepare anything new because of the motto of the show. I have been working with different aspects of various symbols over several years, with the light and the dark aspects. Also I am not a big fan of Tintoretto to whom the motto makes reference. Maybe the main curator had in mind that everyone who visits Venice has some special affinity to Tintoretto and that Tintoretto is a Venetian icon everybody loves. I myself appreciate other Venetians much more, for example Veronese or Carpaccio, but anyway, it’s not up to me to reflect on whether Tintoretto is loved by the Venetians, or not.

There have often been problems with my works, especially with my use of the swastika, a symbol I have been using extensively. The symbols we are confronted with every day seem to be just static and unchangeable signifiers without any meaning. As a matter of fact, this is not true. Take the swastika, for example, an archaic symbol that can be found in many cultures from Greece to Celtic culture or the Eskimo tradition and ancient Rome. Over the course of the time this symbol was almost forgotten until the Nazis began to use it, and from than on it has been connected with the evil and inhumane spirit of humanity per se. But that’s a construction; the symbol per se never changed over time; it is our way of perceiving it that has changed. I work in the Duchampian tradition that puts the beholder at the center.

There have often been problems with my works, especially with my use of the swastika, a symbol I have been using extensively. The symbols we are confronted with every day seem to be just static and unchangeable signifiers without any meaning. As a matter of fact, this is not true. Take the swastika, for example, an archaic symbol that can be found in many cultures from Greece to Celtic culture or the Eskimo tradition and ancient Rome. Over the course of the time this symbol was almost forgotten until the Nazis began to use it, and from than on it has been connected with the evil and inhumane spirit of humanity per se. But that’s a construction; the symbol per se never changed over time; it is our way of perceiving it that has changed. I work in the Duchampian tradition that puts the beholder at the center.

When I was younger I had a strong sympathy for the non-referentiality you can often find in American art under the slogan of “less interpretation.” Later on, as this art had a more and more conformist touch I started to think differently. Many of my recent works take a different stance and require a deeper interpretation because I am reflecting on the relation between form and content, and on the ways in which perception depends on individual mythologies and social environments. Generally speaking most of my works address art itself, they are reflections and sometimes provocative and ironic statements about the supposedly unchangeable and eternal values in art.

DU: Thank you very much for this conversation.

Belgrade, April 1, 2011.

Dietmar Unterkofler (1979) is a University lecturer, curator, writer and art critic. He studied Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies in Vienna and Bologna. From 2003 to 2006 he was a research fellow in the Vienna based Graduate School “Cultures of difference: Transformation processes in Central Europe after 1989”. He worked as an editor and a translator in Vienna, and currently he is a lecturer at the Novi Sad University in Serbia. Recently he published the monograph Miško Šuvakovi? Art as Research together with Nika Radi? and he curated the exhibition Group 143 – Radical Thinking in the P74 Gallery in Ljubljana.

Dietmar Unterkofler (1979) is a University lecturer, curator, writer and art critic. He studied Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies in Vienna and Bologna. From 2003 to 2006 he was a research fellow in the Vienna based Graduate School “Cultures of difference: Transformation processes in Central Europe after 1989”. He worked as an editor and a translator in Vienna, and currently he is a lecturer at the Novi Sad University in Serbia. Recently he published the monograph Miško Šuvakovi? Art as Research together with Nika Radi? and he curated the exhibition Group 143 – Radical Thinking in the P74 Gallery in Ljubljana.