Avdei Ter-Oganian Against the New Russian Idolatry

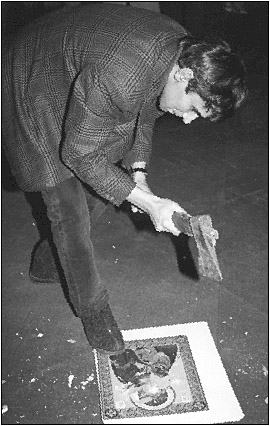

On December 4, 1998 Avdei Ter-Oganian performed in Moscow’s Manezh exhibition hall an action he called the “Desecration of Holy Objects”. Simply speaking, he took an axe and proceeded to chop up photographs of several Russian orthodox icons. The action had grave legal consequences: the Moscow prosecutor’s office started a process against Ter-Oganian, accusing him of arousing national and religious hatred. If found guilty, the artist would spend two to four years in prison. The process against Ter-Oganian is far from over: the municipal court of the Khamovniki district met on April 20, 1999 but then adjourned without reaching a verdict. Ever since then, the media have been debating the artist’s present triumph as well as his possible future sufferings. Common topics that come up in connection this discussion are the symbiosis of the Orthodox Church and the State in post-communist Russia, the patronage of nationalist painters like Ilya Glazunov–who is suspected by Moscow journalists to be the driving force behind Ter-Oganian’s prosecution–by Russian officials and, last but not least, Ter-Oganian’s courage in the face of the not-quite-so-secular new Russian society.

On December 4, 1998 Avdei Ter-Oganian performed in Moscow’s Manezh exhibition hall an action he called the “Desecration of Holy Objects”. Simply speaking, he took an axe and proceeded to chop up photographs of several Russian orthodox icons. The action had grave legal consequences: the Moscow prosecutor’s office started a process against Ter-Oganian, accusing him of arousing national and religious hatred. If found guilty, the artist would spend two to four years in prison. The process against Ter-Oganian is far from over: the municipal court of the Khamovniki district met on April 20, 1999 but then adjourned without reaching a verdict. Ever since then, the media have been debating the artist’s present triumph as well as his possible future sufferings. Common topics that come up in connection this discussion are the symbiosis of the Orthodox Church and the State in post-communist Russia, the patronage of nationalist painters like Ilya Glazunov–who is suspected by Moscow journalists to be the driving force behind Ter-Oganian’s prosecution–by Russian officials and, last but not least, Ter-Oganian’s courage in the face of the not-quite-so-secular new Russian society.

Much less attention is being paid to the artistic meaning of Ter-Oganian’s performance. It is this meaning, however, that explains all the social issues implicit in his “Desecration of Holy Objects”. In fact, the very title of the performance is misleading, which is one of the main obstacles to its proper understanding. Even though Orthdox thinking does attribute a certain religious significance to photographs taken of icons, it would never consider these images “holy objects” in the proper sense of that word. The epithet “holy” is strictly reserved for so-called “miracle-working” icons. These icons produce miracles based on a double referentiality that targets both God and history alike. The photograph of such an icon, on the other hand, has no perceptible historicity. The psycho-physiological reality of the miracle-working icon, its immediate hypnotism, is based on the physical contact with the countless number of parishioners who have prayed in front of it. The photograph of the miracle-working icon eliminates these faithful for the sake of an infinite visuality. The photograph of the icon represents a pure sign of the invisible, stripped of all the remains of idolatry. The materiality of the photograph does not belong to the icon; therefore, a redoubled (photographed) icon simply cannot be cut up or otherwise destroyed. Nevertheless, the horror that results from Ter-Oganian’s action is real: we can see how the blade of the axe penetrates the photograph’s body, destroying its physical presence. For the photograph’s reality belongs to the present: contrary to the miracle-working icon, the “photo-icon” has no history. Its impact is based on the uncertainties of our perception, which is prone to confuse simulacra and real things.

The reconstruction of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow (the project was begun in 1995) was a turning point in the cultural and religious policy of the new Russia. The cathedral, aptly called “the samovar” by Yevgenii Trubetskoi, a conservative Orthodox thinker of the 1900’s, was hardly the most valuable among the hundreds of architectural landmarks that were demolished during the Soviet period. Its reconstruction therefore had nothing to do with the artistic excellence of the past, nor indeed with the artistic barrenness of the present. Instead of creating a “new” religious consciousness (by building new cathedrals), instead of reanimating the “old” one (by restoring old cathedrals), Moscow officials were keen to establish their proximity to the foundations of Christianity. When the mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov (wearing his favorite helmet) ceremoniously added a brick-like cornerstone to the foundations of the “new” cathedral, he thereby appropriated its history, including the concrete emotions of all the believers of the past who prayed in front of the cathedral’s icons. At this point, the still remaining old buildings in Moscow cease to exist: they become self-replicas that dissolve in a virtual reality.

The next logical step after the destruction of the symbolic value of the church would be that value’s inflation or forgery. A good example of such a forgery is a pseudo-ancient building on Bolshaia Polianka Street in Moscow. This building in the “Russian style” was erected in 1993, marked by a conventional plaque: “An Architectural Landmark. Protected by The State”. Interestingly, the brand-new bricks that are the basic building material of the “Russian” house and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior are of exactly the same kind. Being substantially equal to all the other molecules of the Russian construction boom of the 90’s, these bricks simulate the main values of traditional cultures: age, originality, and simplicity. Simulations of this kind can be seen everywhere in the new Russia.

Having nothing to do with either God or history, these simulations easily become a political value. They seem to await the next elections to be sold to an inexperienced consumer as a reflection of his or her self-consciousness. One may assume that the unexpected protection offered by Russian officials to the photographs that were chopped up by Avdei Ter-Oganjan was by no means accidental. For these photo-icons have much in common with the buildings and religious artefacts that have recently been “resurrected” in Moscow.

Journalists have been quick to identify Ter-Oganjan’s action withAlexander Brener’s attack on Malevich’s “Suprematism” (1913). However, Brener’s action falls short of Ter-Oganjan’s act.For when Brener in 1997 desecrated a “holy” icon of modern painting at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk museum, he in fact only affirmed its authenticity: the dollar bill which Brener painted on the canvas was meant to symbolize a “convertible” profanity that was ultimately unable to destroy the painting’s eternal value. Ter-Oganian, by contrast, wielded a real axe–the main symbol of Russian revolutionary culture–to fight a pseudo-historical monster. Preserving the material history of culture, the painter (=WHO?) had to remove from its surface the political cartoon (modernity), eating up history in search of power. After all, it is remarkable that nobody rushed to save the “holy objects” that were “desecrated” by Ter-Oganjan, as had been in the case of the Malevich painting. Instead, the players behind the Russian political stock-market assaulted Ter-Oganian’s artistic practice–and inadvertently removed the religious and historical disguise from their political fictions.