Dictionaries of Friendship: Transnational Artistic Dialogues in First Person Plural

In 1978, Nick Waterlow, the artistic director of the third Sydney Biennale, “European Dialogue,” visited Budapest and agreed with the Hungarian art historian, László Beke that he would put together an informative exhibition of documents and original works covering the activities of several Hungarian artists. Beke, who was by then an internationally renowned advocate of East European Conceptualisms accepted this task but avoided the burdensome role of a national consultant by involving artists not only from Hungary but also from four other socialist countries. As he stated in the catalogue, he did not attempt to make an objective representation of various, then-current tendencies, instead, he invited his artist “friends” from the region to help him compose an idiosyncratic section of the Biennale which he declared his artwork.(László Beke, “Eastern European and Especially Hungarian Art from a Very Personal Point of View,” European Dialogue: The Third Biennale of Sydney (Sydney, 1979), unpaged.)

The Poster of the 3rd Biennale of Sydney, 1979. Courtesy of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

What motivated Beke to shed his role as a “cultural diplomat” and rather aspire to be the co-author of artists with whom he could only communicate in letters written in broken German, French, or English? I trace back the origins of this specific commitment to the close rereading of interactions Beke and Hungarian neo-avant-garde artists had with artists of the other so-called “friendly countries.” Among the many possible more or barely discussed examples, I focus on those in which the usual question of international artistic transactions “who should represent the art of a country or a movement and what larger community an artist may represent” is replaced by or at least contrasted with the interpersonal question “what language we need to speak to enter into a dialogue with the other.”

The paradigmatic significance of the choice of language, translations, incomprehensible or nonstandard use of foreign or hybrid languages was already raised in relation to the practice of East European artists by, among others, Magdaléna Radomska, Magdalena Moskalewicz, and Sven Spieker.(Magdalena Radomska “Podróże środkowo wschodnio europejskich artystów w latach siedemdziesiątych,” [Journeys by Central-Eastern European Artists in the Seventies] in “Sztuka w podróży” [Art on the Move] ed. Tomasz Załuski, special issue, Sztuka i Dokumentacja, nr. 11 (2014): pp. 43–54., Magdalena Moskalewicz, “Languages of Art in Central Europe: Participation, Recognition, Identity” in Understanding Central Europe, ed. Marcin Moskalewicz and Wojciech Przybylski (New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 551–58; and Sven Spieker, “Foreign Language and Utopia in Eastern European Neo-Avant-garde Art,” (conference paper, Theorizing the Geography of East-Central European Art, East-Central European Art Forum, Piotr Piotrowski Center for Research on East-Central European Art, Poznań, 2018) http://piotrpiotrowskicenter.amu.edu.pl/forum/sven-spieker-foreign-language-and-utopia-in-eastern-european-neo-avantgarde-art) What I hope to add to this discussion is to shift attention from the challenges of the Western reception of East European Conceptualism to how artistic cooperation between artists, critics and curators—roles often assumed by the same person—speaking different East European languages were possible at all, and what motivated and what thwarted them. In principle such exchanges would involve a double process of translation from the traveling artist’s or curator’s native language to a mediator language, and then to the local language where their practice is presented. What strategies were worked out to eliminate the flattening effect of this double translation? Then coming back to the wider context of these questions I return to the 1979 Sydney Biennale to examine how the cross-border, interlanguage artistic friendships, collaborations, and confrontations could or could not gain recognition in the context of larger exhibitions of international or global scale.

On April 1, 1972, the Hungarian artists, Gábor Attalai, Imre Bak, and Beke announced the following call:

Considering the international artistic relations became more and more extensive in our days we feel in particular the necessity to intensify these relations first of all among ourselves, namely among the artists of the neighboring countries. We seek the possibilities for cooperation and on this point we also ask for your and your friends’ opinion. [sic](Gábor Attalai, Imre Bak, László Beke, “Dear Friends,” Budapest, April 1, 1972, Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.)

Attalai—otherwise a textile artist—and Bak—a hard-edge painter—joined international networks in the late sixties with the help of publications and the earlier generation of avant-garde artists, but as they gravitated towards Conceptualism they also felt the need to renew this network.

In the case of Beke, in the second half of the sixties and parallel with his art history studies, he had the whimsical idea of taking Slovak language classes as a protest against the historically strained relationship between the two countries.(Beke’s solidarity-based choice of a language to learn was not unique. The editor of both samizdat and “official” art publications, and his wife, Anna Szeredi, who worked as a translator, both started to learn Czech as an act of solidarity when the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968. Beke only acquired basic skills in Slovak, but Hap and Szeredi became so fluent in Czech that they later translated literary works.) Around 1970 Beke, as a research fellow of the Art History Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, participated in several institutional expeditions to socialist countries. On one of these occasions, he made friends with Tomáš Štraus, a bilingual Slovak-Hungarian art historian and critic. Štraus became Beke’s most important reporter on the Czechoslovak scene and his guide and mediator whenever Beke traveled to Slovakia. Štraus also provided inspiration on how to use and subvert the Marxist and sociological terminology of art theory to interpret and legitimize the avant-garde and Conceptualism in a socialist country. They regularly sent each other books, and their recent articles, which they not only discussed but also translated and tried to get published in the other country.

In his 1970 essay “Art as anticipation of social reality,”(Tomáš Štraus, “A művészet mint a társadalmi valóság anticipációja,” Szovjet Művészettörténet, no. 26 (1972): pp. 26–45, also published in French as “L’Art et sa fonction d’anticipation” [Art and its Predictive Function], Revue d’esthétique 1 (1971), pp. 39–48.) Štraus argued that progressive art is not a reflection of synchronous reality, but is essentially an anticipation of future social trends. Later, Beke developed further his Slovak friend’s arguments by applying them to the then-current conceptual trends.(László Beke, “Képzőművészet 2000-ben?” in: Tájékoztató: Magyar Képzőművészek Szövetsége 1. (1975): pp. 11–17.) In the meantime, Štraus also traveled to Budapest to meet the youngest generation of neo-avant-garde artists, and during this meeting, the idea of a friendly meeting between Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists emerged.

In June 1972, Beke, acting as a spokesperson for Hungarian progressive artists, sent out the following invitation: “Dear Friend! Considering the importance of the Czechoslovak and Hungarian artists’ being together and the necessity of the documentation of this event, we propose you to meet us in Balatonboglár.” This invitation set the venue of the meeting in György Galántai’s Chapel Studio in Balatonboglár, which functioned between 1970 and 1973 as a unique, independent, and progressive venue. In the same month as this invitation to the meeting was sent out, Beke drafted, still in the first-person plural, a more elaborate program manifesto titled “‘Concept Art’ as the Possibility of Young Hungarian Artists.” This text explicitly raised the linguistic challenges of international cooperation, but he—or more precisely the artists on whose behalves he acted—still focused on the comprehensibility of artistic languages and not the actual ones:

With the help of these new media, which appear as an international language for us, we would like to provide information about our particular problems and results, and in general speaking about our particular situation.

My friends […] speak poetical / ironical / scientific / symbolic / playful / witty / elegant / shammy / humorous / pseudo / mannerly / constructive / realistic / mystical and other kinds of indirect languages; everybody speaks his own language of pictures, photos, texts, maps, happenings, chess matches, music, film, theatre, statues, nature, spiritism, machines, textiles, human bodies and games, etc.

At the moment I would like to say something not in their language, but in their name and in a direct, non-artistic language.(Published first in the samizdat Szétfolyóirat (edited by Béla Hap, 1972), then as László Beke and Urs Graf, “Junge Kunst aus Ungarn” Werk 10 (1972): pp. 592–8, then in English: “‘Concept’ Art as the Possibility of Young Hungarian Artists,” Hungarian Schmuck, eds. László Beke and Dóra Maurer (South Cullompton: Beau Geste Press, 1972).)

When Beke switched to first person singular, he also defined his own role as the international mediator of these practices. However, the replies of Czechoslovak artists to his invitation put his/their utopian undertaking to test. Many addressees complained that they could not understand English, and replied rather in Hungarian, Slovak, German, or French. They also wanted Beke to specify the subject of the meeting so that they could prepare for it, which Beke did in his next letter written in English, French, and German stating that “the subject of the meeting is THE MEETING, i.e. in our opinion already only the fact that progressive Czechoslovak and Hungarian artists are come together is as important as any kind of artwork.” [sic](László Beke, Dear Friend!, June 10, 1972. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.)

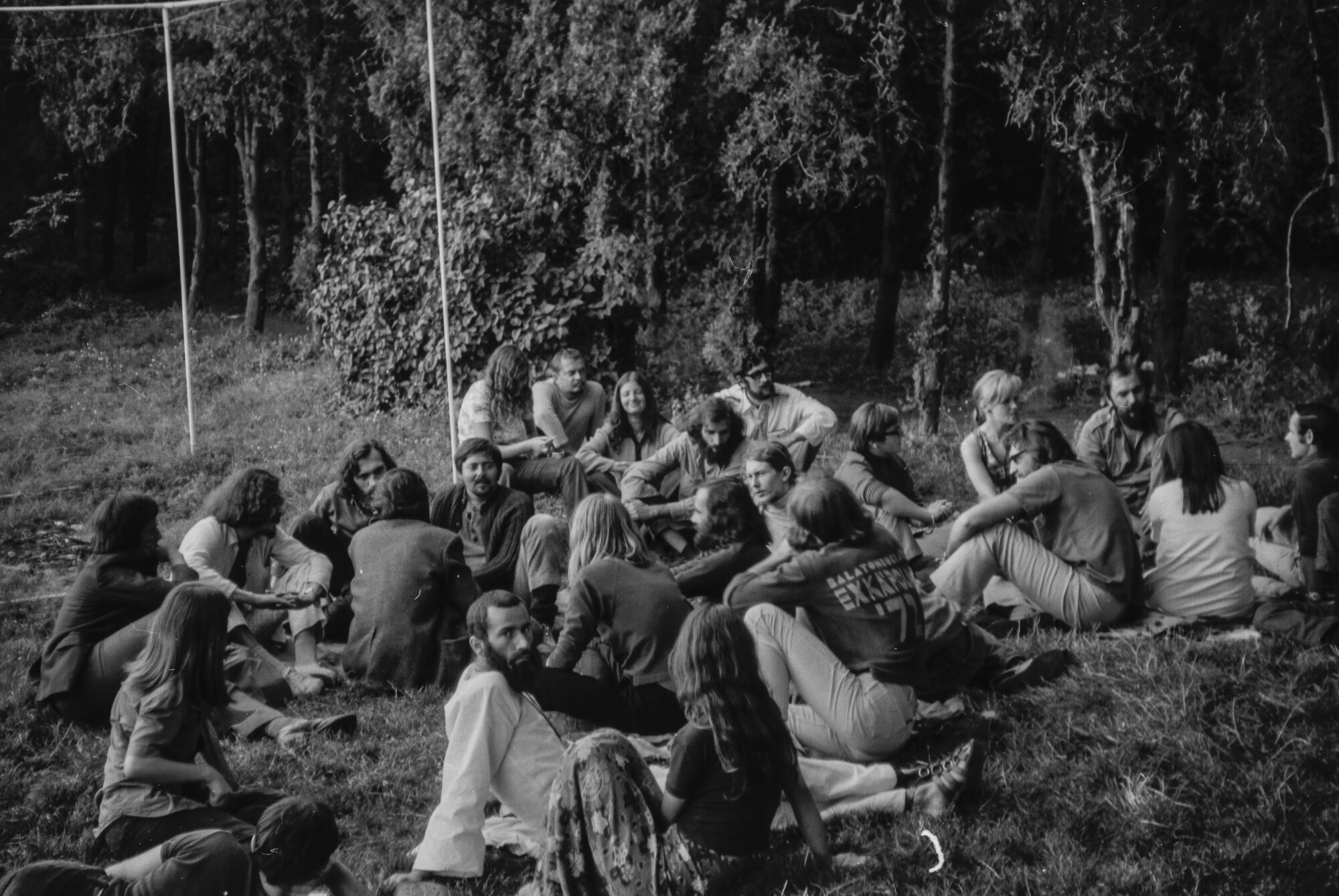

The Meeting of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian Artists, Chapel Studio of György Galántai, Balatonboglár, 1972. Photograph by László Beke. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of the heirs of László Beke.

Not every invitee could identify with this floaty plan, and Štraus decided not to participate either since he was under secret-police surveillance. Finally, four artists from Bratislava: Peter Bartoš, Stano Filko, Vladimír Popovič, and Rudolf Sikora, two from Brno: J. H. Kocman and Jiří Valoch, and from Prague, Petr Štembera came; some of them were accompanied by their female partners. Twelve Hungarian artists from Budapest and some further members of the parallel culture received them, all involved temporarily or more consistently in exploring the potentials of “Concept Art” described by Beke above.(From Budapest, in addition to György Galántai and László Beke, Árpád Ajtony, Imre Bak Miklós Erdély, Péter Halász, Béla Hap, Ágnes Háy, György Jovánovics, Péter Legéndy, János Major, László Méhes, Gyula Pauer, Szentjóby Tamás, Anna Szeredi, Ádám Tábor, and Péter Türk were present.)

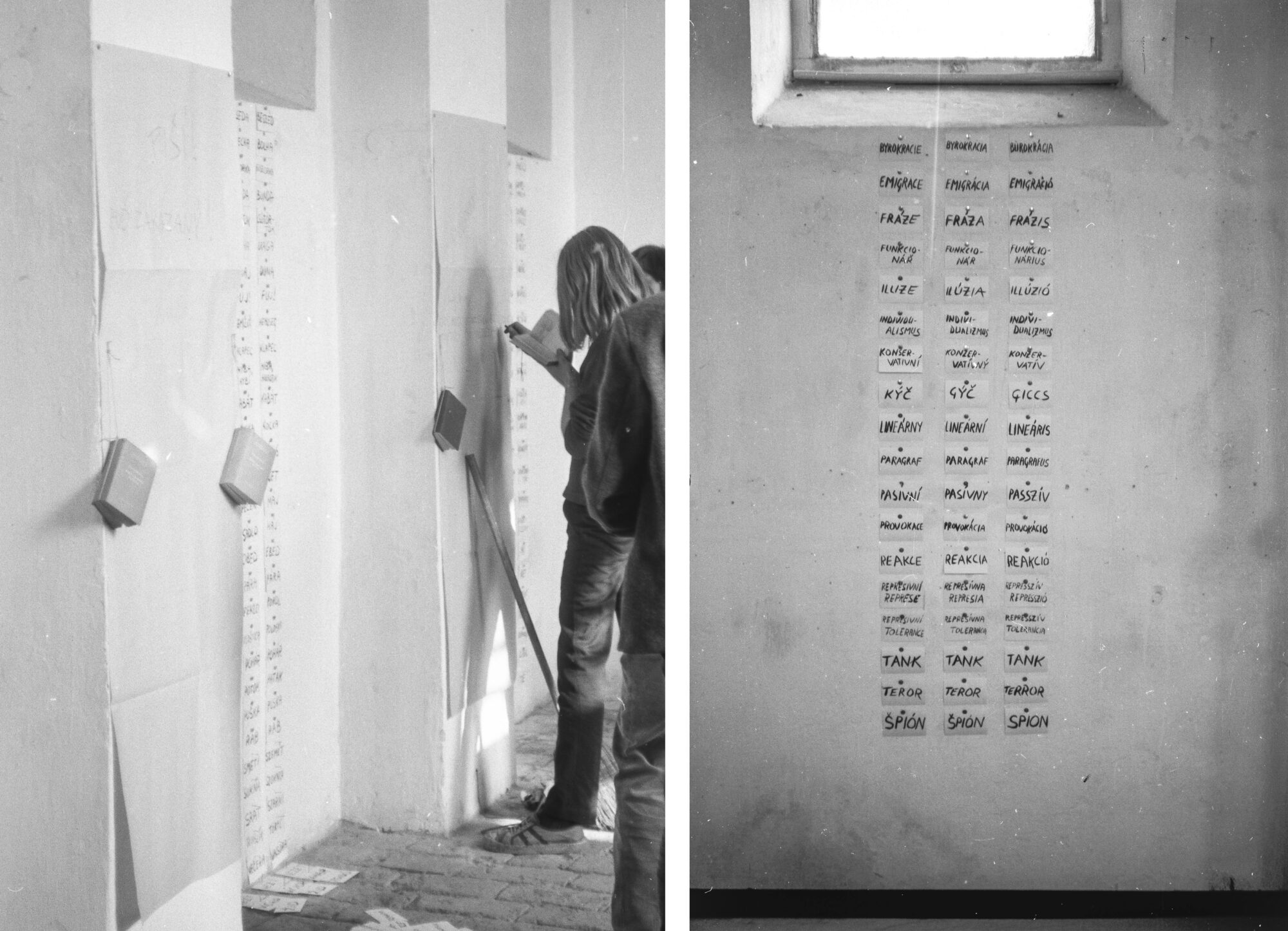

The exchanges preceding the meeting highlighted a blind spot concerning the possibilities opened up by Conceptualism and the utopian desire for transnational artistic communication. This oversight was addressed in a straightforward way at the actual meeting. Beke brought along dictionaries and put them on display so that participants could join him in collecting and displaying similar and mutually understandable Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian words. The linguistic nature of Conceptual art did not only open up possibilities but also compelled artists to translate their works into English, or simply create them in the lingua franca of Conceptual art if they wanted to present them internationally. The creation of concepts in broken English, or dabbling with translations, often proved to be a productive, emancipatory, and liberating exercise in the region, fraught with both revelatory misunderstandings and linguistic permeations. From the late 1960s, multilingual glossaries appeared in the works of several East European artists such as Stano Filko, Petr Štembera, just to name those who participated in the meeting.(Filko’s Ascociace series (1968) or Štembera’s booklet, Private Activities, published in 1972 by International Artist Cooperation contain glossaries in more languages, and Beke also published a French for exhibition visitors copying sample conversations for exhibition visitors adding translation and pronunciation guide too.)

The Meeting of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian Artists, Chapel Studio of György Galántai, Balatonboglár, 1972. Photograph by László Beke. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of the heirs of László Beke.

However, the performative functionality of the collective dictionary action at the Balatonboglár meeting differed from the abstraction of these multilingual glossaries that addressed the unspecified recipient of works circulating in the international network of mail art. The displayed Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian words pointed to a common intersection, a shorter, non-mediated connection, without obscuring the distinctiveness of the three languages and cultural contexts. The similarity was present not only in the phonetic form of the words but also in the connotations and contextual meanings that the participants living in actually existing socialism tended to attribute to these words, as Magdalena Radomska has already shown.(Magdalena Radomska, “Correcting the Czech(olsovakian) Error: The Cooperation of Hungarian and Czechoslovakian Artists in the Face of the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia” in Art beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945–1989). Eds. Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, Piotr Piotrowski (Budapest: CEU Press, 2016) pp. 369–380.) The words of Greek, Latin, or Germanic origin: democracy, demonstration, collective, bureaucracy, individualism, provocation, or tolerance are similar in almost all European languages, but for the participants they had a specific implication to their state-socialist contexts. While the consonant equivalents of more ordinary words such as talk, witch, fur, dear, lunch, hell, cup, stream, kiss, or free, brought to the surface deep layers of the unique relationships between the languages involved.

The triplets of words also emphasized, as Štraus also noted in his letter to Beke, that the meeting was not bilateral, but involved a more complex set of relationships. While artists from Hungary thought to address their counterparts in Czechoslovakia, the art circles in Prague, Brno, and Bratislava were not necessarily fully aware of each other’s activities, and a dynamics of distinction-rivalry-cooperation determined their perceptions of each other. This stratified system of relations appears in the triadic rhythm of identity, similarity and dissimilarity between word triples—for example, akce – akcia – akció (action), but kabát – kabát – kabát (coat), or chyba – chyba – hiba (mistake).

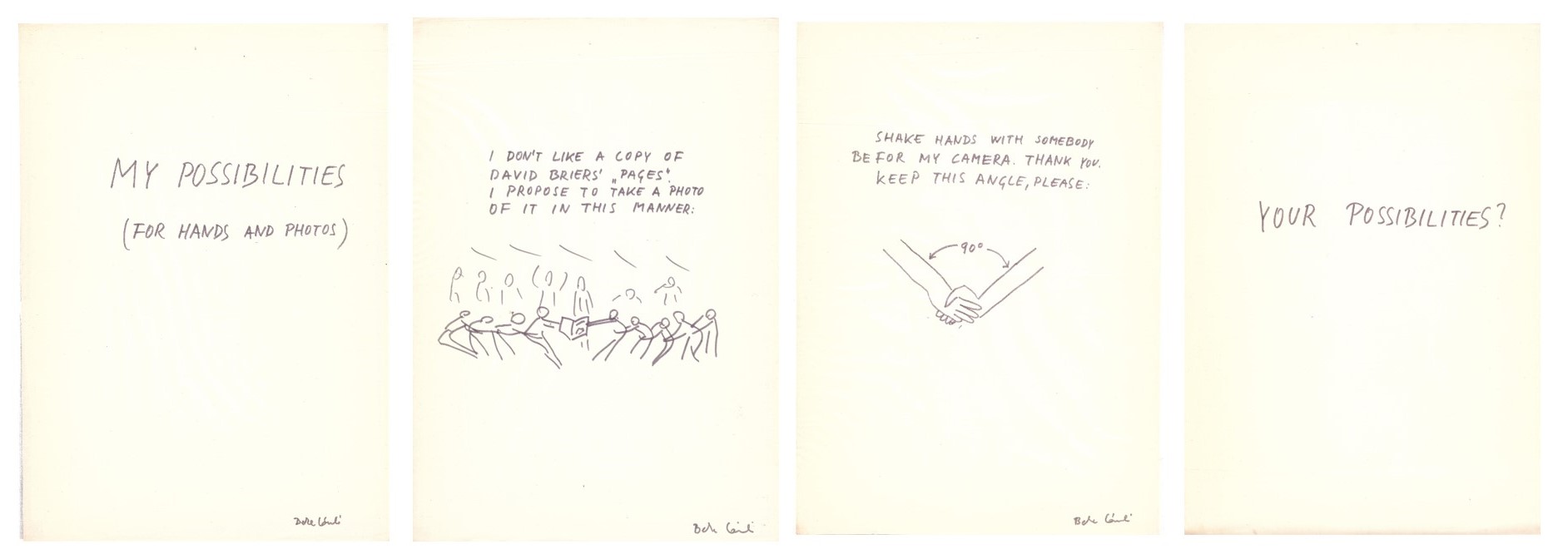

László Beke, Possibilities, marker on paper, 1972. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of the heirs of László Beke.

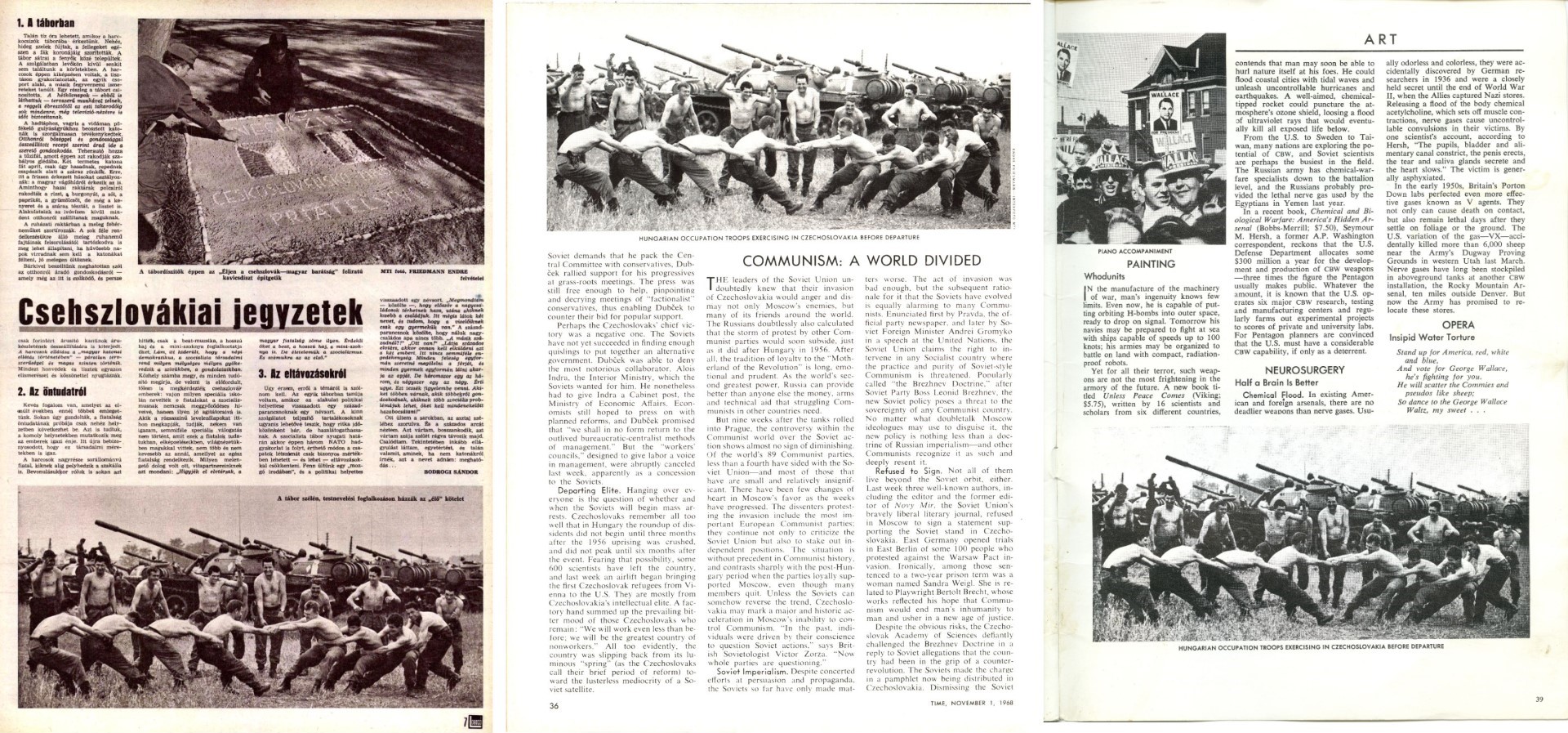

Beke also initiated two other collective actions, entitled Possibilities,(The title was most probably inspired by the text by the Czech writer, Josef Kroutvor, also invited to the meeting: “Möglichkeit, Experiment, Ideen und Kreationen,” Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa (Köln: DuMont, 1972).) which experimented with contextually changing meanings and artistic languages rather than actual ones. One of the actions was motivated by a disturbing photo taken of Hungarian soldiers playing tug of war while stationed in South Slovakia as part of the Warsaw Pact’s combined forces after the repression of the Prague Spring. The obviously staged photo—one of the soldiers was even smiling into the camera was made by the official photographer of the Hungarian New Agency to demonstrate the friendly nature of their stay in Czechoslovakia. This particular photo appeared in Hungarian press alongside another photo of soldiers laying out pebbles that form the inscription in Slovak “Long live Czechoslovak-Hungarian friendship.”(The photographs were made by Endre Friedmann from the Hungarian Press Agency and published in the October 9, 1968 issue of the journal Lobogó on page 7.) However, it was also published in the US Time magazine, next to the headline “Communism: A World Divided,” where the smile of the soldier appeared rather arrogant. Finally, Beke came across the image in the 1970 issue of short-lived mail art magazine Pages partly dedicated to Czechoslovak art, which made a further twist on the interpretation of the photo, here part of a sarcastic montage of clippings from Time to demonstrate the tortures of art under Cold War militarism.

Endre Friedman’s photograph of the Hungarian soldiers in Czechoslovakia in the journal Lobogó (October 10, 1968), Time (November 1, 1968), and Pages (no. 2, 1970).

Based on the frustration derived from this occurrence, Beke proposed to restage and document the tug-of-war scene as a tableau vivant but instead of a rope, pulling on and tearing the Pages magazine and annihilating the notorious photo. What is remarkable is that the participants agreed to reenact this somewhat awkward game even if the repetition aimed to annihilate its image. They all adopted the small role of the bored Hungarian soldiers killing time after participating in the imperialist, repressive intervention. Moreover, they even played out a kind of national-international rivalry—Czechoslovaks against Hungarians—so that the Hungarians fell courteously, while the outnumbered Czechoslovaks “stood their ground.”

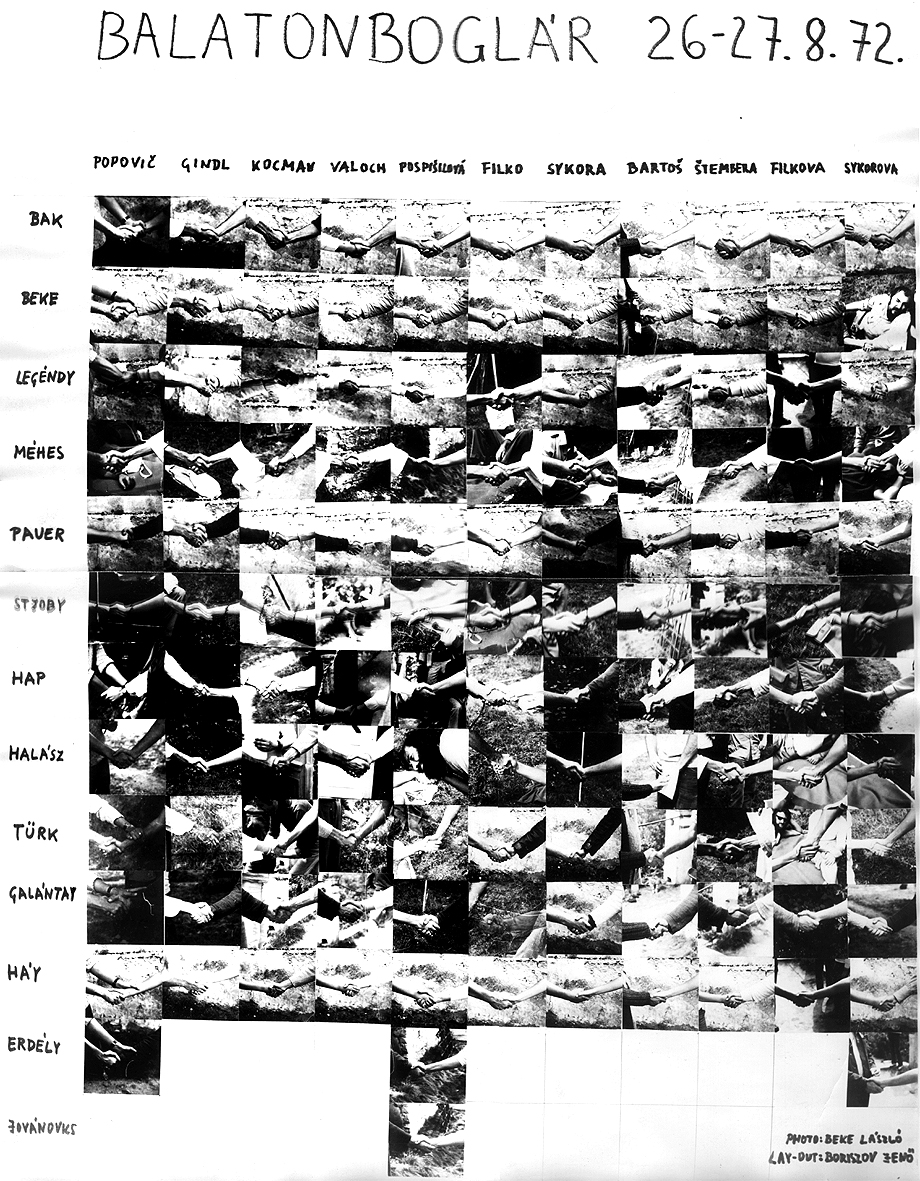

For the other action—similarly as the previous one, prompted by Beke’s sketch—the participants were asked to shake hands with someone in front of Beke’s camera. According to his sketch, the point of this action was to produce handshake photos that create a repetitive rhythm of slight, personal differences in a uniform structure. However, the collective realization of the action was not about documenting possible handshakes, but about each Czechoslovak participant shaking hands with each Hungarian participant. Some weeks earlier Miklós Erdély, also participating in the meeting, screened a twisted filmstrip titled Mobius Film, showing the handshakes of presidents, in a way that the characters on the right and left of the image repeatedly got reversed extinguishing the significance of their position.(László Beke, “Film Möbius-szalagra: Erdély Miklós munkásságáról” (Film on Mobius strip: on Miklós Erdély’s work) Filmvilág (1987/9): 46.)

László Beke, Handshakes, photo-montage of the collective action realized in the Chapel Studio, Balatonboglár, August 26-27, 1972. Photograph by László Beke and Jenő Boriszov. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of the Heirs of László Beke.

Going a step further, the participatory action tested if the interpersonal meaning of this non-verbal gesture can be reclaimed from the diplomatic realm where it often signifies subservience. It is important to note that the handshake action was the only collective activity in which the women present could take part. From Hungary the only female participant of the action was Ágnes Háy, the young film director, and from Bratislava the art historian, Eugenia Sikorova, wife of Rudolf Sikora, and Mária Filková, the editor, translator, and wife of Stano Filko, and Gerta Pospíšilová, the director of the House of Arts in Brno and partner and translator of Jiři Valoch.

Further open proposals to be completed by the participants were also presented as means to find intersections between different artistic languages. Jiří Valoch from his do-it-yourself: signes series handed out sheets of paper, on which a rhombus was printed, which participants had added to in various ways. In a similar fashion, the Hungarian sculptor, Gyula Pauer, got his Pseudo manifesto—which described his program to create self-revealing semblances and manipulations—translated into Czech and asked everyone to make pseudo artworks on his behalf. The meeting was particularly inspiring for the Slovak artist Peter Bartoš, who also initiated two collective, but barely discernible actions that tested the limits of communicability. In his letter written in Slovak—referring to the information that Beke was learning the language—proposed a meditation exercise that cannot be documented: participants were to listen to each other’s invisible and inaudible heartbeats, which he called dorozumenie, meaning “understanding” or “agreement” in Slovak, but also includes the word umenie, “art.”(Peter Bartoš’ letter to László Beke, June 2, 1972. The archive of the First Slovak Investment s. r. o’s art collection.)

Metalinguistic gestures were also employed to explore the limits of discernibility and communication. Adopting the regional folklore practice of “drawing” patterns with sprinkling water on dirt floors, Bartoš wrote letters on the chapel floor that faded away soon but were captured in photographs. In a similar vein, the painter László Méhes drew his utopian slogan with white chalk on the wall and on Pauer’s pseudo sheet: “A new world will be born.”(Dávid Fehér, Méhes László (Budapest: Hungart, 2016), p. 49.) In a more communicative fashion, Tamás Szentjóby, with the assistance of someone who could translate for him wrote visibly on the wall in Czech “Help me a little so that I can help you,” which demonstrated how the cooperative impulse eclipsed any other artistic message. The momentary interpersonal experience of cross-linguistic understanding is well captured by Gyula Pauer’s later account, “I almost learned Czech and Slovak, and they almost learned Hungarian.”(Törvénytelen avantgárd: Galántai György balatonboglári kápolnaműterme 1970–1973, Ed. Júlia Klaniczay and Edit Sasvári (Budapest: Artpool-Balassi, 2003), pp. 141–3.)

This two-day meeting, though it was so familial that it also included some flimsy gags, is still remarkable for exploring the possibilities of direct artistic dialogue not impaired but fueled by local languages and relations. “‘Concept Art” as the Possibility of Young Hungarian Artists,” quoted above, contained a long list of artists and curators with whom the group wished to communicate, many of whom were based in socialist countries. It made explicit that the collaborative desire of Hungarian artists expressed through Beke was not completely fulfilled in “correcting the Czechoslovak error,”(Radomska, “Correcting the Czech(olsovakian) Error.” ) but had a wider scope. However, the often hard-to-read local institutional conditions and dynamics made it a challenging mission to find proper partners for such transnational artistic exchanges even within the socialist sphere.

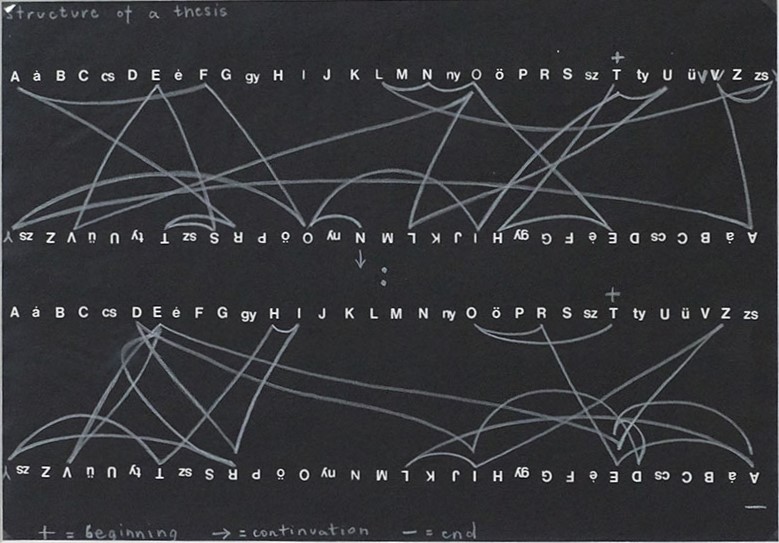

In 1973, at the Tendencies 5 exhibition, in Zagreb, the last in a series of international biennial exhibitions devoted to technical media and (neo)constructivist art, for the first time in the history of the series, works by seventeen Hungarian artists were presented through Beke’s mediation. On this occasion, the exhibition attempted to confront Conceptualism, constructivist visual research, and computer art. In the conceptual section, curated by Marijan Susovski, the chief curator of the City Gallery of Contemporary Art, Beke presented a compilation entitled Anonymous Collective. “Anonymous” here referred to the international collectivist tendency aiming to abandon individualistic art production, but was also a cover for the unauthorized Hungarian participation. Practically, it was a folder containing conceptual works on paper by Gábor Attalai, Imre Bak, Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics, László Lakner, Dóra Maurer, Gyula Pauer, Tamás Szentjóby, Endre Tót, Péter Türk: mental-visual-verbal operations that invited the viewer to complete them. Some artists made their works directly in English, to others Beke added English translations. Attalai, for instance, had sheets of paper stapled together in a geometric pattern with the self-contradictory inscription “Anonymous block by Attalai.” Maurer’s piece was a riddle made of an alphabet board on which lines indicated the itinerary to the letters of her message.(Next year Maurer used the same method in her entry at the Wrocław Drawing Triennial but this time to compare the visual structure of synonymous Polish words. Visual Structure of Words 1-9, 1974. MDL 129. Maurer Dóra, (Budapest, Ludwig Museum, 2008).) Notwithstanding the mediating effort, and the compilation’s alliance with the most cutting-edge metalinguistic, dematerialized tendencies, Beke’s modest folder containing xeroxed sheets could hardly enter into a dialogue with the much larger scale, sensually appealing, interactive works of the exhibition realized from incomparably larger budgets.

Dóra Maurer, The Structure of a Thesis: The Only Way of Arts Evolution: to Realize Every Third Idea, 1972. From László Beke’s Anonymous Collective for Tendencije 5, Galerija Suvremene Unjetmosti, Zagreb, 1973. Courtesy of Dóra Maurer.

The international AICA congress, The Rational and the Irrational in Visual Research: A Match of Ideas, organized in conjunction with Tendencije 5 was to facilitate exchanges between the parallel trends confronted within the exhibition. In his paper delivered in German, Beke criticized this opposition from the perspective of “Eastern European art.” He argued that Conceptual art, which engages with the unknown, through the use of language also rationalizes it. Still inspired by Tomáš Štraus, he claimed that through this dynamism it could anticipate the future and intervene in society. He also stated that the irrational attribute applied to Conceptual art romanticizes it in a similar way as East European art is often exoticized as intuitive and subjectivist. Echoing his “Concept art” manifesto from the previous year, he concluded that, in contrast to its Western aesthetic development in Eastern Europe, Conceptual art is merely an unpretentious medium through which artists can communicate socially and internationally.(László Beke, “Rational und Irrational in Hinsicht einer osteuropäischen Kunst,” manuscript, 1973. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.) While several local advocates of Conceptualism sided with Beke’s criticism regarding the title of the congress, very few papers reflected on the different roles constructivism, computers, and Conceptualism played in capitalist and socialist societies.

Želimir Koščević, the director of Galerija Studentskog Centra, the main forum of New Art Practices found the polarizing approach of Tendencije 5 so outrageous that, as a protest, he placed a note in Croatian, English, and French on the entrance of the Gallery stating that it is closed “because of” the AICA assembly. In his review published in the Gallery’s paper, Koščević accused the congress’s chair, Abraham Moles, of treating conceptual art as if it was a “naughty, irrational, undisciplined child to whom spankings were dealt.”(“T-5: Match of Ideas,” Novine, no. 44. (June 1973): 187–8. Armin Medosch, New Tendencies: Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961–1978) (Cambridge: MIT, 2016), 217–218. Darko Fritz, “Histories of Networks and Live Meetings—Case Study: [New] Tendencies, 1961-1973 (1978),” in Relive: Media Art Histories, eds. Sean Cubitt and Paul Thomas, (MIT Press, 2013), pp 99–118.) This shared frustration could form a long-lasting friendship between Beke and Koščević even if the latter did not share the former’s East European commitment.

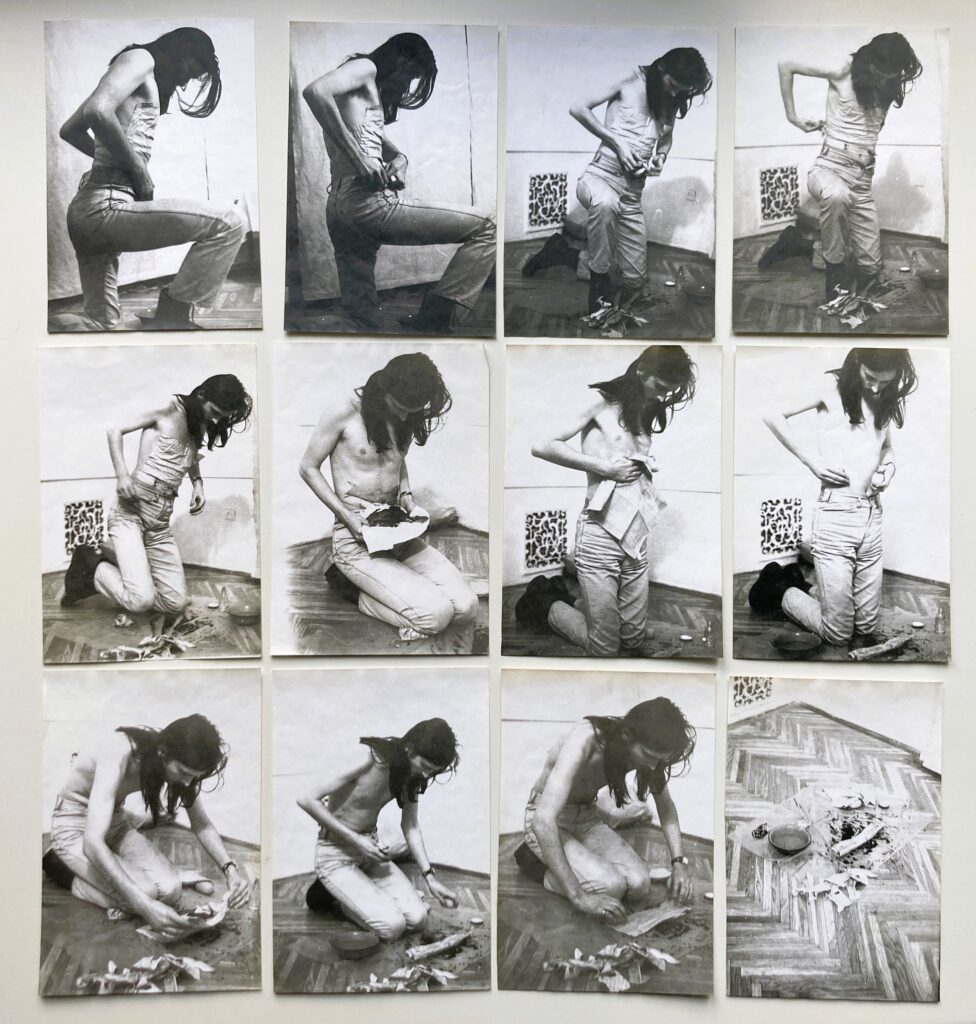

Jan Mlčoch, Zig-Zag-Wiggle-Waggle, 1975. Photos of his action performed in the Young Artists’ Club, Budapest. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of Jan Mlčoch.

Between 1974 and 1977 Beke was in charge of the exhibition program of the semi-public Young Artists’ Club in Budapest and could develop a curatorial program that was informed by this commitment and invite several experimental artists from the region. One of his first invitees was Petr Štembera, who brought with him his regular collaborators, Karel Miler and Jan Mlčoch to present performances and performance photographs.(Štembera represented his piece titled, Narcissus (1974), which involved mixing his blood, urine, nails and hair and drinking this potion. Maja Fowkes, “Embodied Environmental Awareness in the Performative Practice of Czech Artist Petr Štembera in The Green Bloc: Neo-avant-garde Art and Ecology under Socialism (Budapest: CEU Press, 2015), pp. 230–232.) For their 1975 Budapest exhibition leaflet, Beke wrote a poetic text inspired by Mlčoch’s piece entitled Washing, which he performed in 1974 in a non-public room of the Prague National Gallery in front of a few friends. Instead of a usual curatorial introduction, Beke wrote:

I wash for my friends. I undress myself, I reveal my secrets and weaknesses to them, but I only focus on washing. I isolate myself in front of them–they observe my movements with understanding attention–I concentrate on myself–my concentration, fear, and calm are transferred to them.(László Beke’s untitled text on the leaflet of the exhibition of Petr Štembera, Karel Miler, and Jan Mlčoch, Young Artists’ Club, Budapest, 1974 [1975].)

Using the first-person singular, he gave a voice to the fictional artistic self that performs the actions documented in the photographs.

As Beke often stepped over the limits of his role as an art historian and critic to initiate more symmetrical and transnational artistic interactions, artists, such as Dóra Maurer also took upon the task of mediating other artists’ practices across borders. Together with her husband, Tibor Gáyor—a citizen of Austria—they formed in 1970 a collective, called SUMUS (“we are”), in the frameworks of which they organized several international exhibitions, tours, and compiled publications. In the early seventies they used their language skills and double Austrian-Hungarian citizenship to ease their double isolation—not really belonging anywhere—and organize their own transnational community mediating contacts to Western institutions. In the second half of the decade, their attention gradually turned to the East European scene. With the assistance of the filmmaker János Gulyás, they made slide reproductions of the newest works of their fellow artists first locally, then in 1974 they went on a tour to Poland and Czechoslovakia to meet artists and expand their slide collection. Personal contacts established during this tour contributed to several later exhibition exchanges.(Dóra Maurer, “Sumus: Data with Subjective Commentary,” in Parallel Oeuvres (Győr: Városi Művészeti Múzeum, 2001), 127–172.)

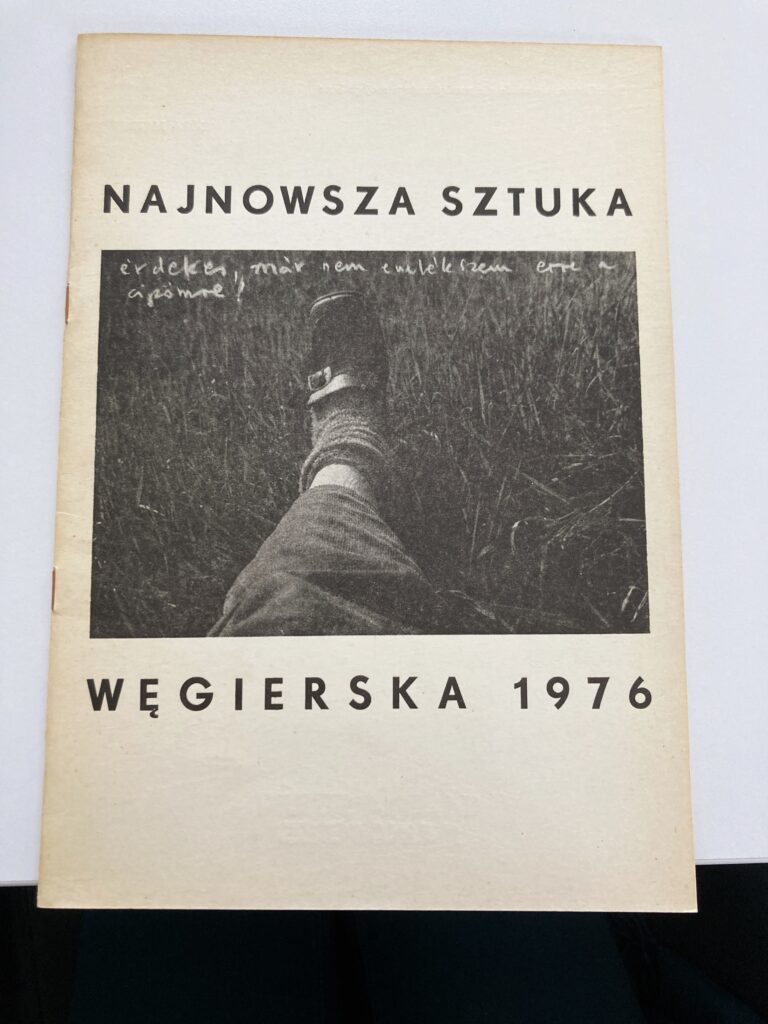

Dóra Maurer’s photo from her Study of Minimal Movements series (1972) with the inscription “Strange, I do not remember this shoe of mine” on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, Najnowsza sztuka węgierska, Galeria Sztuki Najnowszej Wrocław, 1976.

One notable example was between the Wrocław Recent Art Gallery (RAG) run by a younger generation of artists associated with the contextual art movement and a group of Budapest and Pécs artists. The term, contextual art, was coined in early 1976 by Jan Świdziński from Wrocław—a kind of mentor of RAG—and Jean Sellem—the head of St. Petri Gallery in Lund, Sweden—to criticize the purely speculative and linguistic operations of Western conceptualism and internationally propagate a counter-movement that would enter into dialogue with its social context.(The Recent Art Gallery, ed. Anna Markowska, (Wrocław: Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2014).) Some weeks later, in the spring of 1976, among others, Gábor Attalai, Imre Bak, Dóra Maurer, Endre Tót, László Lakner, Miklós Erdély and Gyula Pauer traveled to Wrocław from Budapest to present documentation, interactive installations, screenings, and give talks, individually or in small groups. In connection with this series, the action of Miklós Erdély is worth mentioning since it again reflected on the challenges of transnational artistic communication. Erdély, who only spoke a little French, imitated a conversation with a radio transmitting a program in Polish. As Beke described the action: “the precondition of communication is assimilation—as the radio is both deaf and blind, Erdély also blindfolded himself and plugged his ears” and thus initiated a dialogue with a radio speaking in Hungarian and trying to outvoice it.(László Beke, “The work of Miklós Erdély, a chrono-logical sketch with pictures up to 1985,” in Miklós Erdély, ed. Annamária Szőke (Wien: Georg Kargl Fine Arts, 2008))

Later that year the Pécs Workshop was invited to RAG, and then the following year the Wrocław artists—Stanisław Antosz and Katarzyna Chierowska, Lech Mrożek, Piotr Olszański, Anna Kutera, and Romuald Kutera—were hosted in Pécs, and presented their practice under the heading of “Contextual Art.” As their exhibition was described in the local paper: “the essence of their creative intent is to create a connection between their works and the audience, by activating it. (Hence their name: contextual art).”(L. P., “A wroclawi képzőművészek Pécsett: Galéria Sztuki Najnowszej kiállítása,” Dunántúli Napló, April 14, 1977, p. 2. )

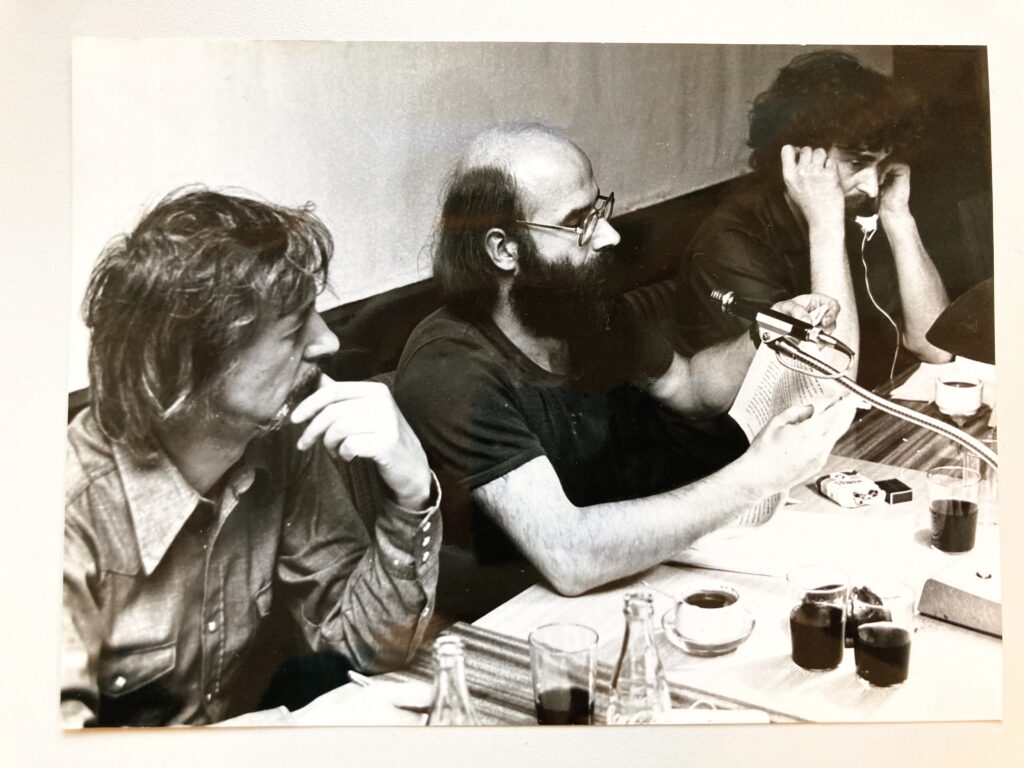

(From left to right) Jan Świdziński, László Beke, and Henryk Gajewski at the “Art as an Activity in the Context of Reality” symposium in Remont Gallery, Warsaw, 1977. Photograph by K. Cybulski. László Beke Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI. Courtesy of Henryk Gajewski.

Świdziński did not travel to Hungary with the younger artists but a month later organized a large-scale international meeting together with Henryk Gajewski (the curator of the Remont Gallery in Warsaw), to which Beke, Štembera, Valoch and Gerta Pospíšilová, as well as Zoran Popović from Belgrade, were also invited. Though a contextual revision of Conceptualism seemed to be congenial in several respects with the aspirations of the Czechoslovak and Hungarian participants, they expressed their reservations regarding Świdziński’s authoritarian movement-making ambition.(The statements presented during the international conference “Art as an activity in the context of reality,” (Remont Gallery, Warsaw, July 1977) were summarized in a press folder.) A close reading of the proceedings suggests that there was an unreflected discord between the vocabularies and idioms they used. Świdziński twenty or even thirty years the senior of the generation emerging in the late sixties and early seventies, used a monolithic, rationalist, abstract vocabulary, whereas Beke, Valoch, and Štembera belonged to a generation that defined itself by the subversion and deconstruction of this monolithic language through utopian, poetical language games, twisted by maverick humor and self-irony.

Two years later, when Beke composed his section for the Sydney Biennale, instead of acting as a spokesperson of a movement he gave an ostensibly impertinent ground—friendship—for his contribution. This edition of the Sydney Biennial raised several controversies even before it opened. Nick Waterlow wished to challenge the center-periphery hierarchies dominating the art world and showcase, in a pluralistic sensibility, artists from both the capitalist and socialist countries of Europe to counterbalance the supremacy of New York. On the other hand, local artist groups requested the director of the Biennale to give equal representation to Australian and women artists, which he could hardly live up to.(Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, “Cultural Translation or Cultural Exclusion? The Biennale of Sydney and Contemporary Art in the South.” In Regionality/Mondiality: Perspectives on Art, Aesthetics and Globalization, ed. Charlotte Bydler and Cecilia Sjoholm (Stockholm: Sodertorn University Press, 2014) pp. 265–293.) Circumventing the heated debates on equal representation, Beke claimed that he could only represent his own subjectivity, which, however, included his artist friends in an extended sense. He also played around with the idea of fair representation and asked Waterlow to allocate equal space—one square meter—to each artist he invited. In case someone’s work would not arrive in time, he proposed to keep an equal space empty for them and only display their names. As he explained to Tamás Szentjóby, the Hungarian artist, who he identified in his catalog text as his best friend: he proposed to present artists as his artistic media and vice versa his section also served as a medium through which artists could present themselves.(László Beke’s letter to Tamás Szentjóby, February 1979. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.)

In addition to eleven Hungarian artists active in fields ranging from performance to experimental photography, theatre, or textiles,(The Hungarian artists in Beke’s section were: Anikó Bajkó, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, György Jovánovics, Dóra Maurer, Gergely Molnár, László Najmányi, Gyula Pauer, Zsuzsa Szenes, Tamás Szentjóby, János Vető.) Beke invited others from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Artists from these countries featured in Beke’s miniature Eastern Europe section, for example, the Cluj artist, Ana Lupaș, a frequent participant of international textile triennials within and beyond the region; Milan Knížák, the “director of Flux-East,” and his compatriot, Petr Štembera, prominent member of mail art, body art, and performance scene; Raša Todosijević from Belgrade known for his provocative performances; and the internationally less recognized Marek Konieczny from Warsaw with his “Think Crazy” program, and Jacek Stokłosa, from the Krakow Druga Grupa famous for their participatory installations. Beke called these artists his friends, even if he had never met some of them. As he wrote in the catalogue: “Friendship for me means common fate, that is a kind of love, euphory, torture and base hostility, but first of all, a fatal synchronicity.” [sic] (Beke, “Eastern European,” unpaginated.)The common element in this constellation, which Beke declared to be his artwork, was the liminal approach to Actionism and performativity with strong conceptual, interpersonal-dialogic, poetic, and contextual peculiarities.

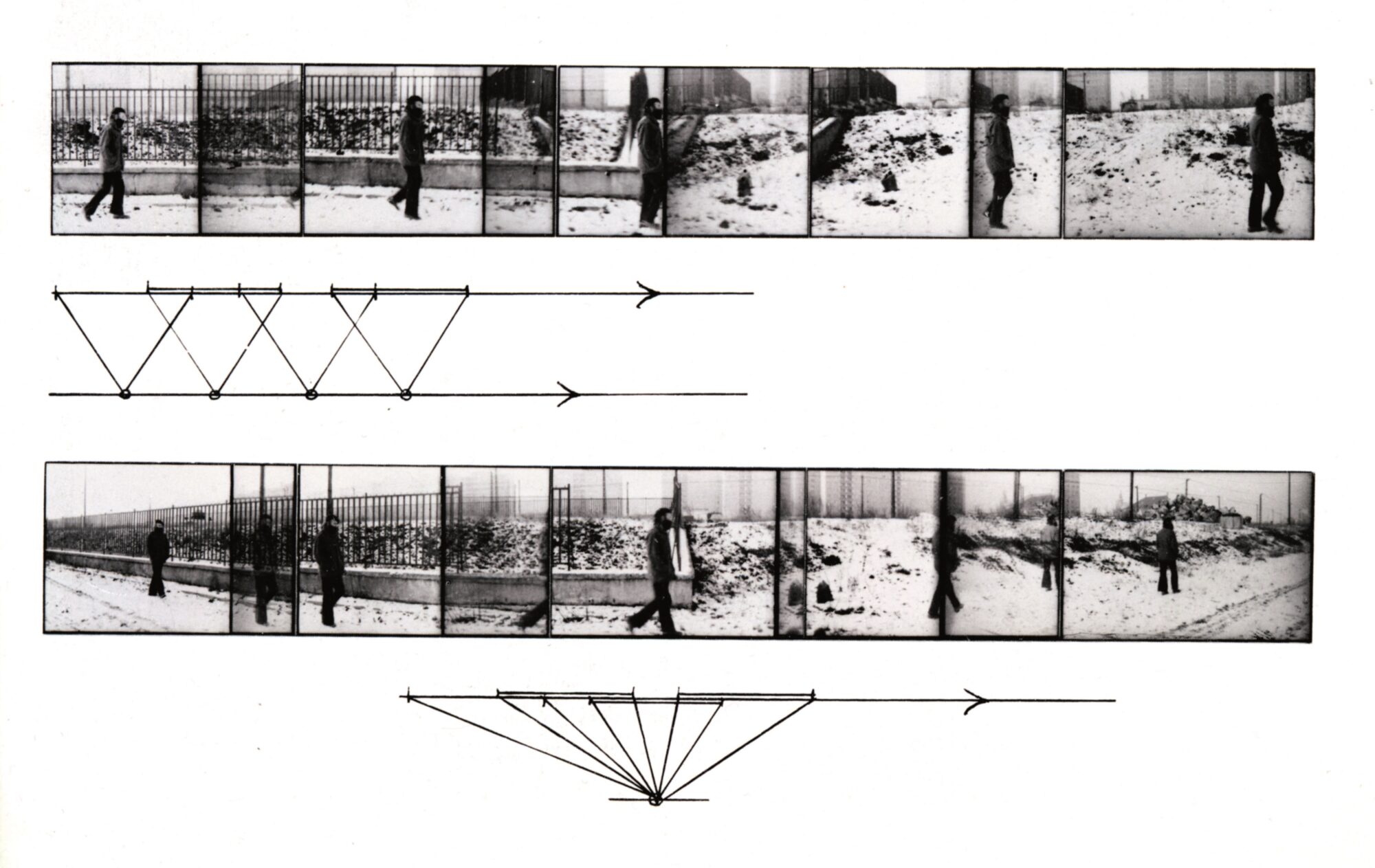

Dóra Maurer, Parallel Lines, photo-action with László Beke (MD 170), 1978. Courtesy of Dóra Maurer and Vintage Gallery.

Interpreting “European dialogue” in the biennial’s title more literally than intended he asked for works that are about his person, thus initiated a creative exchange, a kind of co-authorship with the participants. Jacek Stokłosa gave a blunt reply to this proposal and sent a photo series of a car on which Beke’s name is written in the dirt. Dóra Maurer, also in a playful spirit, involved Beke in a new variation of her photo interaction series (for one, two, or more cameras). Beke was asked to walk on one side of the street and Maurer on the opposite side was trying to follow the path and the pace of his movement with her camera. Tibor Hajas, the internationally renowned protagonist of the performance movement, initiated a more provocative dialogue. He wrote a statement for the Biennale that had a drastic effect on Beke.(Tibor Hajas, “Statement for the Sydney Biennale (1979),” published in Hajas Tibor [1946–1980], eds. László Beke and György Széphelyi F. (Paris: Magyar Műhely, 1985), p. 333.) The speaker in Hajas’s text describes a horrifying vision, images of death, suffering, violence, the destruction and shaming of the human body, and robbing of human dignity. As he wrote, these images haunted him and they stop time because they are irredeemable, just as the perfect, total moment is what he sought in his performances. It seems that Hajas intentionally provoked in Beke the dilemma of whether he could accept this text as his “own work,” which Beke confronted in a reply, expressing the torture Hajas’s statement had caused him.(László Beke, To T. H., 1979, manuscript. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.)

Ana Lupaș wrote a letter to Beke in broken Hungarian and posed three possibilities: 1. he can send an enclosed photo and the instructions for creating an object-collage it depicts made of an electric motherboard, 2. follow the instructions, create the piece himself and send it to Sydney 3. send whatever he pleases.(Ana Lupaș’s letter to László Beke, no date. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.) Beke chose the last option and sent a different, textile piece by Lupaș most probably since he wished to create a dialogue between her practice and recent experiments in Hungarian textile art. In his catalogue text, Beke gave special attention to women artists, though rather stereotypically, focusing on female artists working with textiles. Thus Ana Lupaș’s textiles functioning as projection screens for individual or collective psychic processes could be compared with Zsuzsa Szenes’s, who experimented with textile applications transforming minimal spaces and Anikó Bajkó’s, who presented photos of vast biomorphous heaps of industrial textile damaged or destructed through natural or chemical effects.

In the end, Beke did not get a visa to travel to Sydney and only received Waterlow’s report stating that his section “formed an interesting contrast with the more lavishly presented works.”(Nick Waterlow’s letter to László Beke, June 29, 1979. Archive of László Beke, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.) The publication European dialogue: a commentary issued after the event to present the press coverage of and debates around the Biennale contains some reproductions of the photo works in Beke’s section (by Štembera and Maurer among others), but also demonstrates that the intentionally low profile, personal exchanges between Beke and some East European artists, could hardly make their voices heard.

This chain of transnational resonances that coalesce around the curatorial projects of László Beke highlights the necessity to complement existing historical accounts of East European Conceptualism that focused on national narratives, western influences, dissident strategies, or networking. Beyond momentary contact through mail, exhibitions, and meetings this entangled historiography seeks meaningful dialogues developed between artistic, critical, and curatorial practices within the region. Such interactions involved a dialectics of congeniality and provocation and gave a crucial role to mediation and translation and depended on the willingness to abandon the comfort of your mother tongue and delve into the often uneasy relational complexities of—to modify further Piot Piotrowski’s term—the even closer other. As these case studies revealed the fault lines that hindered cross-border communication were not necessarily defined by borders but more by artistic vocabularies and mentalities that either embraced or fought against their own peripherality. Thus friendship, when freed from its hypocritical diplomatic connotations and understood as an interpersonal emancipatory process, even if it could not subvert the hierarchies of the globalized art world, became an artistic medium that could transcend generations, borders, and languages.

This article is an extended and reworked version of the conference paper “Dictionaries of Friendship: László Beke’s East-European Project and Agency in Cultural Transfer and Translation”, (Beyond Friendships: Regional Cultural Transfer in The Art of the 1970s, KEMKI, Budapest, 2022) which was published in Hungarian as Zsuzsa László, “A barátság szótárai: Beke László Kelet-Európa-projektje,” Enigma110 (2023), pp. 55–66.

This article is part of a Special Issue on Regional Resonances. You can read other articles from this Special Issue published on ARTMargins Online below: