When Letters Show Their Muscles: A Conversation with Sabine Hänsgen and Tomáš Glanc about the Traveling Exhibition Poetry & Performance, the Eastern European Perspective

Subversive humor often emerges from emergency situations. Those who cannot say what they are thinking invent secret languages, play with suggestion, parody what is permitted and mutilate it into mere sounds, or put up slogans in remote areas. In states where verbal expression is subject to strict control – i.e. censorship – poets and thinkers infiltrate the official discourse by imaginatively torpedoing it. In those countries formerly behind the Iron Curtain, poetry became an experimental field for criticism, as well as a retreat from ideology and language politics.

The traveling exhibition Poetry & Performance. The Eastern European Perspective presents a selection of these experiments. The first edition premiered at New Synagogue in Žilina, Slovakia, in 2017. It is currently on view at the Motorenhalle in Dresden until July 7, 2019, with further showings planned for Wrocław (Poland), Dnipro (Ukraine), Budapest (Hungary), and Liberec (Czech Republic). Each edition of the exhibition is characterized by a place-specific orientation with a special focus on the respective local context. The exhibition and its varying contexts is the subject of the below conversation with Sylvia Sasse, Professor of Slavic Literatures at the University of Zurich, and the show’s curators, Sabine Hänsgen and Tomáš Glanc.

Ewa Partum, “Active Poetry,” film still, 1971/1973. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sylvia Sasse: Poetry that takes place not just between the covers of a book but on the stage or on the street is currently experiencing a boom. We might read this as a reaction to the impoverishment of political and public language. Your exhibition Poetry & Performance. The Eastern European Perspective takes a look back at the era of state socialism in Eastern Europe. Even back then, artists were reacting to political conditions using the pleasure of language and ironic wordplay to oppose the narrowing of thought into slogans.

Tomáš Glanc: Whenever public and political language becomes impoverished or cynically instrumentalized, poetry, or this kind of “self-attuned language,” becomes a medium of reflection and criticism. And so it is definitely no coincidence that artists in Eastern European autocracies experimented so much with language.

Sabine Hänsgen: Poetic performance shows not only the material and medial dimension of language–as in concrete or visual poetry–but also its situational dimension. This allowed a widely diverse set of possibilities of linguistic expression to be played out artistically. So it wasn’t just about reflection, but also about the development of alternative options for acting and speaking in authoritarian societies.

SS: So would you say that there is a special relationship between poetry and performance in Eastern Europe?

SH: Yes, that’s what we’re trying to draw attention to with the title of the exhibition. With the triple “P” of poetry, performance, and perspective, we are also drawing a connection to a research claim that while performance art in Western Europe and North America can be understood as a reaction to late capitalist consumer culture, performance art in Eastern European cultures meant, above all, engagement with the political-ideological culture as a culture of texts, manifestoes, instructions, and slogans. However, the focus on artistic positions in Eastern Europe does not imply a territorialization of the topic. With the term “perspective,” we seek a change of viewpoint –including our own–to open up new horizons for the reflection on what language can do.

SS: The slogan as a genre of art is an idea you encounter repeatedly in the exhibition. These are not your traditional kinds of slogans, but rather radically poetic, philosophical, meditative, and Dadaist slogans.

SH: Yes. Artists in Poland, the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia, for example, were working with poetic slogans independently of one another. The Polish artist Ewa Partum used letters made of the white cardboard sold in shops to assemble slogans for the decoration of living and working spaces. She randomly scattered these letters in both urban and natural spaces, and in this way liberated them from their original meaning. She called this work “active poetry.”

The Collective Actions Group in Russia hung a sloganned banner in the forest rather than on the street on January 26, 1977. The banner bore the following inscription: “I complain about nothing and like everything, despite the fact that I have never been here and know nothing about this place.” The slogan banners were socially and ideologically functionless, both because of their spatial and temporal misplacement and because of their inscription with poetic texts in the form of aphoristic riddles or koans. In this way, the emptiness of political formulas is exposed and then transcended in a Zen-inspired aesthetics of emptiness.

Collective Actions Group, “Slogan,” photograph, 1977. Image courtesy of the artists.

SS: The fact that the Collective Actions Group hung their slogans in the forest was also related to the state’s fear of performances, actions, or happenings in Eastern Europe – with the exception of Yugoslavia and Poland. They were considered too Western, too related to the avant-garde, and too unpredictable. Under these conditions, it was not exactly easy to connect poetry with performance.

SH: Almost everywhere, poetic performance was only able to be realized in private spaces, such as apartments and studios, or outdoors in nature, which was less under state control. It was possible that the state feared that public performances would compete with the ritualized communication forms of everyday politics, or even make fun of them. That was at least the case in the Soviet Union and East Germany. In Yugoslavia and Poland, on the other hand, it was possible to intervene in public space.

TG: The poetic happenings of the Orange Alternative group in Poland were often based on wordplay or parodies of public holidays. In 1987, they demonstrated in Wrocław with the slogan “Precz z (u)pałami,” or “Away with the heat” in English – a totally absurd demand. But if you remove a single letter, then “upały” (heat) becomes the word “pały” (truncheons), and the action is now called “Away with the truncheons.” This was a reaction to police violence during Martial Law after the prohibition of Solidarity.

Orange Alternative, ‘’Away with Heat (Away with Truncheons),’‘ 1987. Photodocumentation: Piotr Lewiński. Image courtesy of the artists.

SS: The artists not only needed to find spaces for their actions, they also needed to assume those functions normally reserved for the literature or art industries. Was poetic performance also an alternative form of publication and a practice of record keeping and documentation?

SH: When I came to Moscow from West Germany to study in the early 1980s, I was fascinated by precisely these forms of artistic self-organization in the subcultural milieu. They were developing apart from the culture of state socialism, but also apart from the market. Books were being self-published and poems presented in front of a small audience of friends, which is to say other poets, artists, and theorists. In this way, an intimate public sphere developed that was characterized by participation instead of consumption. I personally recorded some of these actions with the video camera I smuggled into the Soviet Union. Considering the ever more totalizing commercialization of art on a global scale, these forms of self-organization can also serve as stimulation in the search for alternative forms of communication and cooperation today.

TG: In state-managed cultural politics, islands sometimes emerged that were neither private nor subject to the state. These intermediate spaces played an especially large role in Yugoslavia, one example being the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, which after 1968 became an internationally recognized site for experimental and neo-avant-garde aesthetics. Here, “active poetry” also took place without internal or external censorship.

Another example was the program “Semester of Experimental Creation” – considered both aesthetically and politically radical – on Czechoslovakian state radio in 1969. The small “peripheral” studio Liberec was able to regularly broadcast the program. These were phonic experiments on the borderline between poetry and music that seriously interrogated language while simultaneously spreading funny, insightful experiments through state-run mass media channels. The famous “sound poet” Ladislav Novák was the spiritus agens of this activity.

It was also in Czechoslovakia in 1969, that a young poet, Václav Havel, composed the Director’s Cut of Czechoslovakian History, an audio composition made up of fragments of speech. He used historical speeches and simple speech sounds, nonverbal language defects. In this way, he confronted history with its own (linguistic) waste.

Liberec Radio Studio, where Semester of Experimental Creation was recorded, c. 1962. Image Courtesy of Pavel Novotný Collection, Liberec.

SS: The Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin once said that literature is not simply the use of language but the artistic recognition of language. This is especially true, it seems to me, of situational poetry, which targets every dimension of language and speaking: the body which articulates it, the media which transmit it, and the spaces where it appears.

SH: Yes, in contrast to solitary, silent reading, performance brings a text into a situational context of perception by viewers and listeners. Mimicry, gestures, and especially tone, intensity, and the rhythm of the voice come into the center of attention.

Katalin Ladik, ‘’UFO Party,’‘ photograph, 1970. Image courtesy of Katalin Ladik, and acb Gallery, Budapest.

This can be seen forcefully in our exhibition in the works of Hungarian artist Katalin Ladik. In her performance UFO Party (1970), voice is not just a medium for making semantically meaningful statements – the voice takes on a life of its own and also acts against the meaning of the text. Through the uncoupling of word meanings, Ladik’s poetry becomes pure sound poetry. In combination with bodily elements of archaic ritual and shamanistic mythology, this leads to the transgression of the boundaries between poetic performance, music, and body art. The Hungarian language played a crucial role in the development of this abstract soundscape for Ladik. It was a foreign and minority language in Vojvodina, the region in Yugoslavia where Ladik lived at the time.

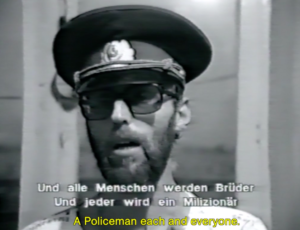

SS: There are also contemporary works in the exhibition, including poetic performances by Roman Osminkin, Babi Badalov, Slobodan Tišma, and Pussy Riot. When members of Pussy Riot ran onto the field in the World Cup final in militia uniforms, almost nobody knew that they were referencing the “The Militiaman” by Dmitri Prigov, a cult figure in Russian poetry. You can see and hear Prigov’s “Militiaman” in the exhibition, as well as read Pussy Riot’s manifesto. Why is Prigov so important for contemporary poet-activists?

SH: In this instance, we see and hear Prigov during a reading in his apartment in Belyaevo, a sleepy suburb of Moscow. In his probably most famous text cycle of the 1970s, the poet-militiaman becomes, as an ambiguously presented cult figure, the mediator between heaven and earth, a representative of a higher “sacral” order. The video recording also brings this into the picture: a close-up frontal shot in unusual lighting lends the poet-militiaman in his uniform cap an iconic countenance.

Dmitri Prigov, ‘’The Militiaman,’‘ video still, 1985. Image courtesy of Hirt/ Wonders.

When the Militiaman stands here at his post

The whole expanse till Vnukovo unfolds before him

The Militiaman gazes to the West and to the East

And emptiness unfolds beyond them

And the center, where the Militiaman stands –

A view of it unfolds from everywhere

From everywhere the Militiaman can be seen

From the East the Militiaman can be seen

And from the South the Militiaman can be seen

And from the sea the Militiaman can be seen

And from the sky the Militiaman can be seen

And from beneath the earth …

It’s not like he tries to hide

To this day, this work remains a provocative and disturbing self-stylization, when the underground poet slipped into the role of a guardian of state order – even if accompanied by an ironic gesture. One of Prigov’s important impulses here is his effort to deconstruct the voice of power, especially as transmitted by mass media. Deconstruction of this kind always remains highly relevant for the following generations.

TG: Contemporary attitudes add to and rework the refined engagement with the power of language and the language of power in the underground. In March 2018, on the day of the (orchestrated) elections in Russia, the performance poet Roman Osminkin staged a wordless performance based on a play on words in Russian, where the term for “voting” translates as “giving your voice.” Here, he attempts to pull his own voice from his throat, from his body, in order to fulfill his duty as a citizen. The voice or vote refuses to come out, however, and despite his best efforts. Osminkin, by the way, is also a loyal and explicit devotee of Prigov.

Roman Osminkin, ‘’How Roman Sergeevich went to give his voice,’‘ video still, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

SS: The exhibition presents 150 works by fifty artists and poets from ten different countries. But it is not that easy to make a public exhibition of poetry. How did you solve this problem in Zurich?

TG: A number of young architects from Prague designed a white structure entirely made of paper for the Shedhalle. Seven transparent pavilions or white cubes lend organization to the room and become a medium for the poetry. When you step into them, you can watch and listen to video recordings at your leisure. The center of the exhibition has been consciously left empty. If you stand in this empty middle, you can hear scraps of language from the sound showers that are spread out over the room. But we also see poetry on the walls, on bodies or fabrics, written in ink, paint, or blood. The exhibition is a work in progress where we’re continually expanding our knowledge and cooperating with co-curators from various countries. And we’re going to be taking the exhibition on the road; planned stops so far include Dresden, Wrocław, Dnipro, Budapest, and Liberec.

SS: Is the act of curating a kind of research by other means?

SH: Part of our intention was to dig up cultural treasures, to bring initial attention to certain authors and approaches that we ourselves first discovered through our research. With our exhibition, we are also able to contribute to the interrogation of a canon oriented towards Western European and North American works and theories. The late Polish art theorist Piotr Piotrowski opposed the West-centered vertical model of art history by offering a horizontal, polyphonic, and dynamic paradigm of critical art-historical analysis. In the spirit of his theoretical tradition, we want to generate attention for a number of lesser-known attitudes and voices, and to prepare a possible revision of the historiography of performance art.

Installation view of “Poetry & Performance: The East European Perspective,” Motorenhalle Dresden, 2019. Image courtesy of Andreas Seeliger.

Translated by Brian Alkire

For more on the history of this exhibition, visit the website for the project Performance Art in Eastern Europe at the University of Zurich: http://www.performanceart.info/exhibitions/poetry-performance/