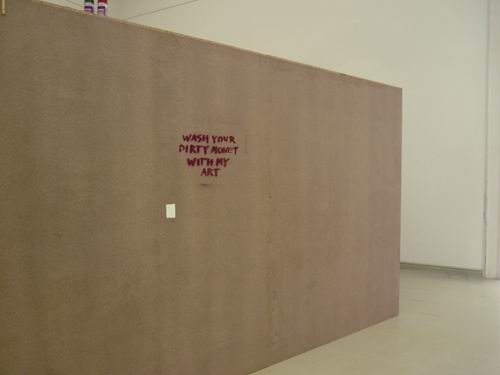

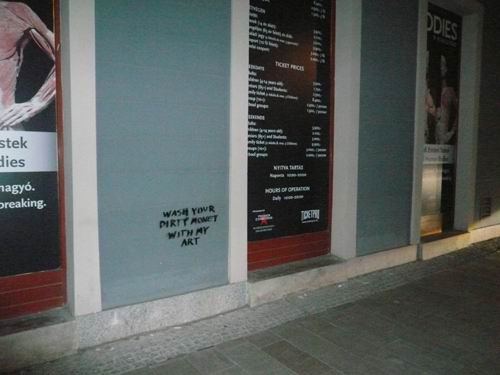

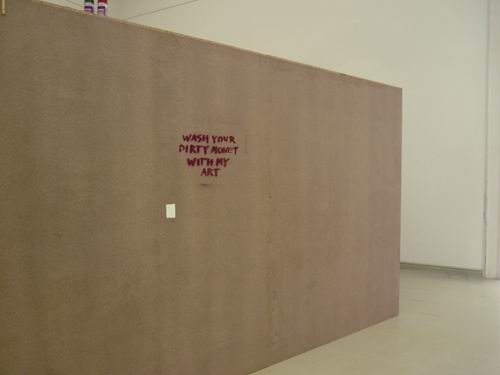

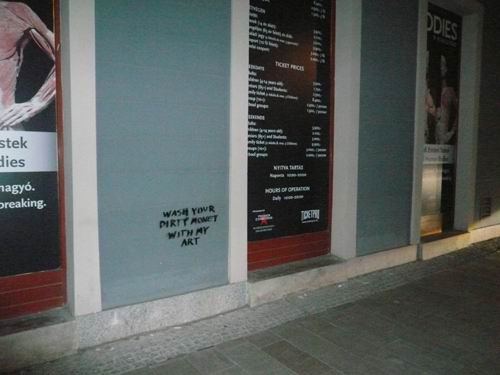

In the summer of 2008, János Sugár exhibited the sentence “Wash your dirty money with my art” at the Kunsthalle, Budapest, as part of an exhibition entitled What’s up?() Parallel with exhibiting the sentence in this safe context, he also displayed it on the pavement in front of and on the wall of two private art institutions in Budapest. Soon after this, one of these institutions sued him for damaging its property. After Sugár’s exhibition at the Kunsthalle it was easy to identify him as the artist, and soon Sugár was summoned by the police and prosecuted. Sugár admitted that he had sprayed the sentences and added that he considered them a continuation of the art work he had earlier displayed at the Kunsthalle. However, Sugár’s gesture was not deemed art by the authorities and was classified as vandalism. The damage was estimated at $7,500, a startling amount given the relatively small pavement area covered by the sprayed text (40×60 cm=1.3×1.9 ft). Sugár refused to pay such a high amount and a second estimate was made, this time at the expense of the artist, who refused to pay this second amount as well. According to the Sugár he is being sued for an artistic gesture, while the owner of the art institution refuses to accept it as art and demands compensation. Sugár’s trial is pending a new damage estimate is under way.

Hedvig Turai: Where did the phrase “Wash your dirty money with my art” come from?

János Sugár: I have a few sentences that I have been working with. Questions or statements like, “What question would you most like to respond to,” “Seemingly small things determine seemingly big things” or “Work for free, or do work you would do for free.” I always keep a notebook with me and jot down notes.

H.T.: Was the sentence that triggered this legal issue one of those?

J.S.: I would begin earlier. In 2007, within the framework of the German-Hungarian Bipolar project, I participated in an exhibition at the Kunstverein in Wolfsburg, Germany. There I exhibited a stencil pattern with the sentence “Work for free, or do work you would do for free.” I sprayed one copy on the wall of the exhibition space and left the stencil and some spray paint there so that visitors could borrow it and take the stencil out into the town. They could have completely covered the walls of this “Volkswagen town.” I did the same piece later in Berlin, where it actually was borrowed and graffiti sentences were sprayed in various places in the city. I happened to be in Berlin when I set down this sentence in question today. A couple of weeks later, already in Hungary, I found again in my notes, “Wash your dirty money with myart.” The sentence struck me because I understood it as it is a reference to street art. It was interesting for me to think of it this way; you put out something using the tools of street art, which can be literally washed off.

J.S.: I would begin earlier. In 2007, within the framework of the German-Hungarian Bipolar project, I participated in an exhibition at the Kunstverein in Wolfsburg, Germany. There I exhibited a stencil pattern with the sentence “Work for free, or do work you would do for free.” I sprayed one copy on the wall of the exhibition space and left the stencil and some spray paint there so that visitors could borrow it and take the stencil out into the town. They could have completely covered the walls of this “Volkswagen town.” I did the same piece later in Berlin, where it actually was borrowed and graffiti sentences were sprayed in various places in the city. I happened to be in Berlin when I set down this sentence in question today. A couple of weeks later, already in Hungary, I found again in my notes, “Wash your dirty money with myart.” The sentence struck me because I understood it as it is a reference to street art. It was interesting for me to think of it this way; you put out something using the tools of street art, which can be literally washed off.

H.T.: So, what does the sentence mean?

J.S.: There is an ambiguity, a semantic play in it, as well as a critical tone. It is a certain kind of offering of one’s self, here I am, wash your money with me, use me to wash your money. All money by definition is dirty, all money is polluted with blood. By coincidence, I gave the presentation and actually exhibited the work at a show at the same time, and visitors could have borrowed it and take the stencil out into the town.() Somewhat later at a conference on graffiti art organized by the municipal government of Budapest, the city launched a campaign titled “I love Budapest.” The idea was that activists would clear the city of graffiti. Budapest has devoted 50 million HUF (about 250,000 dollars) to this purpose. So, when I found the sentence in my notes, I connected it with the anti-graffiti movement, with “washing” dirty money, and that the thing that should be washed was art itself. All these things are connected, and this is the meaning of the sentence. Also, a young artist duo, SZAF(), Miklós Mécs and Judit Fischer invited me to contribute to their exhibition box in the Kunsthalle as part of the exhibition What’s Up?

J.S.: There is an ambiguity, a semantic play in it, as well as a critical tone. It is a certain kind of offering of one’s self, here I am, wash your money with me, use me to wash your money. All money by definition is dirty, all money is polluted with blood. By coincidence, I gave the presentation and actually exhibited the work at a show at the same time, and visitors could have borrowed it and take the stencil out into the town.() Somewhat later at a conference on graffiti art organized by the municipal government of Budapest, the city launched a campaign titled “I love Budapest.” The idea was that activists would clear the city of graffiti. Budapest has devoted 50 million HUF (about 250,000 dollars) to this purpose. So, when I found the sentence in my notes, I connected it with the anti-graffiti movement, with “washing” dirty money, and that the thing that should be washed was art itself. All these things are connected, and this is the meaning of the sentence. Also, a young artist duo, SZAF(), Miklós Mécs and Judit Fischer invited me to contribute to their exhibition box in the Kunsthalle as part of the exhibition What’s Up?

H.T.: Where else did you place that sentence?

J.S.:

J.S.: In two more venues. On the wall of the building of VAM Design Center in Király street, Budapest and on the pavement in front of the KOGART() building. VAM Design Center is the institution that three years ago announced that although in Hungary one needs 20 years to become successful, they can make an artist successful in two and a half years. I have several problems with this. First of all, it is a very attractive but empty slogan, a sham. It does not clarify what success is. What is success and why does it take exactly 20 years to reach it? What does it mean to be successful? I think it is an important part of art that it needs time to enter the network of understanding. The later this understanding or success comes, the more exciting and valuable that art is. The art that we cannot immediately take in is intriguing, bothersome, upsetting; it does not blend in well, and this is what makes it valuable and interesting. What they advertised is a simplified concept of success. It does not do any artist –let alone young artists– much good to think that if they are not immediately successful there is something wrong with them. Plus what I know about the practical side of it makes me very upset. Does simply selling works of art constitute success? On the one hand, this is a rather naïve concept, on the other, it shows a rather superficial knowledge of how the contemporary art works institutionally. So I thought I’d put out my stenciled, sprayed sentence in

What’s up? this young and funny exhibition in the Kunsthalle, and wait to see what happens if I put the same sentence into another context, onto the wall of some private contemporary art institution, and not legally but illegally.

H.T.: Why is money dirty, what is the connotation of “dirty”?

J.S.: I connect it to the naïve, early socialist, leftist way of thinking. As Brecht said, “What is the robbery of a bank, compared to the founding of a bank.” Now that the world is in a financial crisis, it seems that it has even more meaning.

H.T.: Was it a provocation?

J.S.: Yes, it was a provocation, but a provocation can be reacted to and understood in several ways. They could have said, how great that we have a work of art here. A ball was lobbed for them to bat back. They could have preserved it, capitalized on it – tried to sell it, for example. I chose the other venue in the same vein. In the case of KOGART, what bothered me was how this private institution has ignored art professionals’ opinion and work, and how it applies for and receives state funding, state sponsored money. I think neither side really understands the role of the state and the private collector. Some private entrepreneurs consider contemporary art a form of cheap and easy PR. In a way, they use contemporary art for business the same way they use a restaurant.

H.T.: So, although the sentence is ambiguous, the venues that you chose are actually your statements.

J.S.: I think it looks evil only to those who harbor evil thoughts. “Money laundering” is the correct English expression. On the other hand it really is ambiguous, and really funny.

H.T.: How long did your inscriptions remain readable on the wall and on the pavement respectively?

J.S.: It is hard to tell. It was summer, I was traveling, and by the time I came back, in late August, both had been covered. KOGART had a somewhat different, and from my point better, more rational reaction to it. There is a fence between the building and the pavement, so in this case, I had no chance to spray on the wall. The pavement is not private property, and to put graffiti on the pavement is not damaging private property. In case of VAM Design, I was well aware that I painted on the wall, on private property and I damaged private property. It was in late August that I learnt about what happened earlier. In a few days, after I put the sentence ontothe wall of VAM Design, policemen showed up in Studio Gallery. Studio Gallery is an association of young artists to which Miklós Mécs belongs. The policemen were looking for him. He also happened to be abroad at the time, so the policemen could not contact him. It is rather exceptional that policemen in uniform go to a gallery in search of an artist, to investigate a graffiti case. It was rather easy to find Miklós Mécs as a starting point, since “Wash your dirty money with my art” was shown in their booth in the above-mentioned exhibition in the Kunsthalle. In a few weeks, he received a letter requesting him to report to the police. When he went to the police station, some of us, accompanied him, and I assured him that he could admit that it was my work.

H.T.: Were you clear about the legal consequences of this action?

J.S.: I tried to ask for advice but I could not really reach anybody. I received a phone call on the very same day that Miklós Mécs went to the police station, and I was called in after a week. It is obvious that I could have denied it, and that it would have been difficult to prove my authorship. But I wanted to take it upon myself. However, I got myself into something that had several unexpected aspects. When the interrogation began at the police station, we had a long and actually quite interesting conversation about graffiti, art, what art is and is not, and so on. But sooner or later the police investigator had to go into the heart of the matter. I was treated as a criminal, that is, my fingerprints and palm prints were taken, registration photographs were taken of me, and later my apartment was subjected to a search. They were searching for the stencil pattern of the text. They could not find it since I had discarded it.

H.T.: What is the punishment for damaging private property?

J.S.: It depends on the amount of damage. This was classified as damage of high value. According to the estimate of the specialist asked by VAM Design, the value of the damage, that is, restoring the damage caused, was HUF 1,463,000 (approximately 7,500 USD). The policeman also referred to the possibility of my being charged with public libel. It is still not clear, since there has not yet been yet an official filing of charges.

H.T.: Have you been able to ask for legal advice since then?

J.S.: Yes, I went to TASZ.() Their lawyer said that it was a simple case; it was a matter of the physical damages. I acknowledged the damage that I made, which must be compensated, and the only question was how much I was obligated to pay. And it was pretty obvious that to repair the relatively small size of the surface damaged cannot cost 1,463,000 HUF. If they charge me with libel, that is a different matter and they should prove it. The text itself is not defamation, it is ambiguous or can be interpreted in a number of ways. As I said, I think it looks evil only to those who harbor evil thoughts. If they think it is libel, it is their interpretation.

H.T.: So we are back again to the point — do you consider this a semantic problem while they consider it a legal problem?

J.S.: For me the text is connected to theliteral process of washing off graffiti, that is, to the fact that it is good business both to sell the paints to paint graffiti and the liquids to wash them off.

H.T.: Where is the process now?

J.S.: About a month ago I was called in to the police station again. They presented me with the estimate of the cost to repair the damage, asking if I would accept it. I refused. Now they need to ask for another estimate. At the moment I am waiting for the official filing of charges and the actual trial.

H.T.: It seems to me that there was a silence or at least not much publicity around what happened. What were the reasons? And what was it that has changed the situation, that you are now giving interviews about it?

J.S.: I did not really remain silent about it. A small circle of art professionals and friends knew about it. I also sent the photos of the wall and the pavement with the inscription to the internet journal, Exindex, where they were covers for a while with the caption “What next?” () So, the photos had been on the cover before the police investigation started.

H.T.: You have talked about attention deficiency, and you expressed your opinion several times that Hungarian contemporary art scene is suffering from attention deficiency syndrome. Why did you not use this opportunity to generate attention? Even if it is a scandal, scandals are good for capturing attention.

J.S.: It was summer, sort of a dead season for art, and I was also awaiting the outcome of my other project proposals, which I did not really want to endanger with a scandal. I also wanted to see what would happen. I thought that the filing of charges would happen sooner and that I could clearly see what the charges were against me. Also, a scandal is a little different when it happens to you. And, I must add, that it is a more complex situation to have the same work in a legal art context and outside of it. But of course I have been thinking about this problem of attention. In Hungary, solidarity is missing, although there were several occasions when solidarity and mutual support could have been practiced. To mention just two examples, solidarity could have been expressed when Little Warsaw’s work, the re-contextualization of the János Kovács Szántó() statue aroused harsh emotions, or in the case of the removal of László Rajk’s 56’memorial. Ours is a scene that cannot defend itself, that cannot generate discussions that would culminate in producing important works of art. I was wondering if I had enough stature to provoke solidarity of this scene. After the police interrogation, I felt that what I did was a kind of solidarityinvention. I felt solidarity with those that went through something similar. I consider my work a public artwork; this is not street art, I have my name publicly, openly attached to it, and the reactions raised by a public artwork are parts of it. I hope that this work will be a good opportunity to discuss the sensitive points of the Hungarian contemporary art scene; among others, that those who have money and power think they have a power in art as well. We need more impact, more momentum. It would be very useful if this would be the last drop in a pot that would trigger discussion of other problems as well.

H.T.: If this is a public work, then it may have a positive outcome.

J.S.: Yes, there is an implicit possibility to discuss this artistic gesture.

H.T.: But your critical artistic gesture is interpreted as a criminal act, which is sort of censorship, a new type of censorship of money. Generally art provides a defense. Why do you think “Wash your dirty money with my art” was not granted the status of art and thus lent art’s defensive value?

J.S.: Today freedom of speech is seriously controlled. Art is the last refuge of the freedom of speech, a space in which it must be carefully guarded and totally preserved. As I see it, in our society, art is a space where things can work differently, in opposition to one another, against the grain. This way, suggestions could be made for previously unrecognized or unforeseeable problems. It is important to keep watch over this field, so that inspiration for these potentials can be born here. Solutions for future problems can be found only if we keep watch over this freedom, and guard against losing this freshness. Art remains almost the only basis for freedom of speech.

H.T.: What is the best and the worst scenario that you expect to happen?

J.S.: The best is that an amount will be defined, it will be a realistic amount of payment for the damage and I will pay for it.() Then, I need to find out how it can be corrected that now I have criminal record. Also, there is much interest in the work already. A private collector has already bought it and exhibited it; it was also exhibited in Berlin in Lada Gallery’s stand at an art fair, and although the curator was a little a hesitant, not wanting to offend anybody, she said that actually there was much interest in it. The Hungarian Museum Ludwig is interested in buying it as well. There is the potential to trigger a discussion on the situation of Hungarian contemporary art. I hope that it could lead to strengthening the position of contemporary artists, and artists could draw some conclusions from it.

H.T.: What do you want artists to learn from it?

J.S.: That they can be more radical and that there is a scene that can defend them, that is behind them, that shows solidarity.

H.T.: And the worst scenario?

J.S.: I do not think that there really is a “worst” scenario. There is a very narrow-minded attempt to influence public opinion against graffiti. It should be recognized that those who make graffiti belong to the same society, and they are the children of the decision-makers, who actually shaped present society. These kids will pay the pensions of today’s adults, and they are not alien oppressors or idiots. Rather, graffiti should be paid attention to, and their message should be properly understood.

Hedvig Turai is a former contributing editor to ARTMargins. She lives and works in Budapest.

Conceptual artist János Sugár studied in the Department of Sculpture at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest (1979-84). Between 1980-86 he worked with Indigo, an interdisciplinary art group led by Miklos Erdely. His work includes sculpture, installations, performances, video, film, as well as theoretical writing and publishing. He served on the board of the Balazs Bela Film Studio (1990-95) and has been teaching art and media theory at the Intermedia Department of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts since 1990. He has exhibited widely throughout Europe, including at Documenta IX, Kassel (1992). Sugár’s films have been screened at the Anthology Film Archives in New York in 1998.

In connection with János Sugár’s spraying the sentence “Wash your dirty money with my art” on the wall of the VAM Design Center in Király Street in Budapest, there has been a new development. The artist was summoned to appear in court and was accused of having damaged the building. The damage had initially been estimated at 1,400,000 forint (appr. $7,000 in 2008) and was later revised to 214,000 forint ($1,040). It has now been reduced to 34,000 forint ($150). During the trial Sugár acknowledged once again that he did spray the sentence but did not admit to any guilt as he considers the spray painted sentence a work of public art and socially useful because it generates discussion and raises social awareness.

The court did not share the artist’s reasoning, calling the work instead an instance of graffiti and vandalism. The court also did not admit the testimony by two art historians. Apart from the fine the judge imposed a jail sentence of five months in jail which will be suspended for two years. The jury considered it an aggravating factor that the sentence was spray painted on a building that was considered a landmark, and that the work is now on a display in a museum. The jurors also blamed the artist for making money from what they deem an act of vandalism and noted that as a teacher he did not set an appropriate example for his students. In Hungary the spraying of graffiti is considered a socially dangerous activity punishable by fines and even prison terms. János Sugar will appeal the sentence.

J.S.: I would begin earlier. In 2007, within the framework of the German-Hungarian Bipolar project, I participated in an exhibition at the Kunstverein in Wolfsburg, Germany. There I exhibited a stencil pattern with the sentence “Work for free, or do work you would do for free.” I sprayed one copy on the wall of the exhibition space and left the stencil and some spray paint there so that visitors could borrow it and take the stencil out into the town. They could have completely covered the walls of this “Volkswagen town.” I did the same piece later in Berlin, where it actually was borrowed and graffiti sentences were sprayed in various places in the city. I happened to be in Berlin when I set down this sentence in question today. A couple of weeks later, already in Hungary, I found again in my notes, “Wash your dirty money with myart.” The sentence struck me because I understood it as it is a reference to street art. It was interesting for me to think of it this way; you put out something using the tools of street art, which can be literally washed off.

J.S.: I would begin earlier. In 2007, within the framework of the German-Hungarian Bipolar project, I participated in an exhibition at the Kunstverein in Wolfsburg, Germany. There I exhibited a stencil pattern with the sentence “Work for free, or do work you would do for free.” I sprayed one copy on the wall of the exhibition space and left the stencil and some spray paint there so that visitors could borrow it and take the stencil out into the town. They could have completely covered the walls of this “Volkswagen town.” I did the same piece later in Berlin, where it actually was borrowed and graffiti sentences were sprayed in various places in the city. I happened to be in Berlin when I set down this sentence in question today. A couple of weeks later, already in Hungary, I found again in my notes, “Wash your dirty money with myart.” The sentence struck me because I understood it as it is a reference to street art. It was interesting for me to think of it this way; you put out something using the tools of street art, which can be literally washed off. J.S.: There is an ambiguity, a semantic play in it, as well as a critical tone. It is a certain kind of offering of one’s self, here I am, wash your money with me, use me to wash your money. All money by definition is dirty, all money is polluted with blood. By coincidence, I gave the presentation and actually exhibited the work at a show at the same time, and visitors could have borrowed it and take the stencil out into the town.(<http://ruganegra.uw.hu/stencilshow/stencil.html> and <http://ruganegra.uw.hu/stencilshow/prez.html>) Somewhat later at a conference on graffiti art organized by the municipal government of Budapest, the city launched a campaign titled “I love Budapest.” The idea was that activists would clear the city of graffiti. Budapest has devoted 50 million HUF (about 250,000 dollars) to this purpose. So, when I found the sentence in my notes, I connected it with the anti-graffiti movement, with “washing” dirty money, and that the thing that should be washed was art itself. All these things are connected, and this is the meaning of the sentence. Also, a young artist duo, SZAF(SZAF: Szájjal és Aggyal Fest?k Világszövetsége – AMBPA – Association of Mouth and Brain Painting Artists of the World. <http://szaf.blogspot.com>), Miklós Mécs and Judit Fischer invited me to contribute to their exhibition box in the Kunsthalle as part of the exhibition What’s Up?

J.S.: There is an ambiguity, a semantic play in it, as well as a critical tone. It is a certain kind of offering of one’s self, here I am, wash your money with me, use me to wash your money. All money by definition is dirty, all money is polluted with blood. By coincidence, I gave the presentation and actually exhibited the work at a show at the same time, and visitors could have borrowed it and take the stencil out into the town.(<http://ruganegra.uw.hu/stencilshow/stencil.html> and <http://ruganegra.uw.hu/stencilshow/prez.html>) Somewhat later at a conference on graffiti art organized by the municipal government of Budapest, the city launched a campaign titled “I love Budapest.” The idea was that activists would clear the city of graffiti. Budapest has devoted 50 million HUF (about 250,000 dollars) to this purpose. So, when I found the sentence in my notes, I connected it with the anti-graffiti movement, with “washing” dirty money, and that the thing that should be washed was art itself. All these things are connected, and this is the meaning of the sentence. Also, a young artist duo, SZAF(SZAF: Szájjal és Aggyal Fest?k Világszövetsége – AMBPA – Association of Mouth and Brain Painting Artists of the World. <http://szaf.blogspot.com>), Miklós Mécs and Judit Fischer invited me to contribute to their exhibition box in the Kunsthalle as part of the exhibition What’s Up? J.S.: In two more venues. On the wall of the building of VAM Design Center in Király street, Budapest and on the pavement in front of the KOGART(KOGART: A private museum in Budapest, named after entrepreneur, art collector and owner Gábor Kovács.) building. VAM Design Center is the institution that three years ago announced that although in Hungary one needs 20 years to become successful, they can make an artist successful in two and a half years. I have several problems with this. First of all, it is a very attractive but empty slogan, a sham. It does not clarify what success is. What is success and why does it take exactly 20 years to reach it? What does it mean to be successful? I think it is an important part of art that it needs time to enter the network of understanding. The later this understanding or success comes, the more exciting and valuable that art is. The art that we cannot immediately take in is intriguing, bothersome, upsetting; it does not blend in well, and this is what makes it valuable and interesting. What they advertised is a simplified concept of success. It does not do any artist –let alone young artists– much good to think that if they are not immediately successful there is something wrong with them. Plus what I know about the practical side of it makes me very upset. Does simply selling works of art constitute success? On the one hand, this is a rather naïve concept, on the other, it shows a rather superficial knowledge of how the contemporary art works institutionally. So I thought I’d put out my stenciled, sprayed sentence in What’s up? this young and funny exhibition in the Kunsthalle, and wait to see what happens if I put the same sentence into another context, onto the wall of some private contemporary art institution, and not legally but illegally.

J.S.: In two more venues. On the wall of the building of VAM Design Center in Király street, Budapest and on the pavement in front of the KOGART(KOGART: A private museum in Budapest, named after entrepreneur, art collector and owner Gábor Kovács.) building. VAM Design Center is the institution that three years ago announced that although in Hungary one needs 20 years to become successful, they can make an artist successful in two and a half years. I have several problems with this. First of all, it is a very attractive but empty slogan, a sham. It does not clarify what success is. What is success and why does it take exactly 20 years to reach it? What does it mean to be successful? I think it is an important part of art that it needs time to enter the network of understanding. The later this understanding or success comes, the more exciting and valuable that art is. The art that we cannot immediately take in is intriguing, bothersome, upsetting; it does not blend in well, and this is what makes it valuable and interesting. What they advertised is a simplified concept of success. It does not do any artist –let alone young artists– much good to think that if they are not immediately successful there is something wrong with them. Plus what I know about the practical side of it makes me very upset. Does simply selling works of art constitute success? On the one hand, this is a rather naïve concept, on the other, it shows a rather superficial knowledge of how the contemporary art works institutionally. So I thought I’d put out my stenciled, sprayed sentence in What’s up? this young and funny exhibition in the Kunsthalle, and wait to see what happens if I put the same sentence into another context, onto the wall of some private contemporary art institution, and not legally but illegally.