Visual Tactics at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, September 2009-January 2010 (Exhib. Review)

Blickmaschinen oder wie Bilder entstehen. Zeitgenössische Künstler schauen auf die Sammlung Werner Nekes, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, September 2009-January 2010.

The curators of the Blickmaschinen exhibition attempt to answer the question of how the image of the world appears, how it manifests itself, and how it is received and interpreted. The issue of the ontological status of representation was virtually absent in the discourse of art history until the late 20th century. With the emergence of post- structuralism, however, a lively process of re-negotiating the status of representation began. James Elkins lists a few of the starting points for this revival of debate on the concept of the gaze in the twentieth century, including Riegl’s analysis of the Dutch group portrait, Sartre’s theory of seeing and being seen, Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s conception of embodied seeing, Lacan’s psychoanalytical elaboration of the latter, the emergence of feminism and the notion of the “male gaze,” and Svetlana Alpers’ examination of the representation modi, typical to Dutch art.(James Elkins, The Visual: How It is Studied, chapter from a work in progress, available on- line: www.jameselkins.com.) In the case of the Blickmaschinen exhibition, the curators concentrated on the function, perception, and the origins of the image, instead of being concerned with its message and symbolic content. We can identify this same mode of thinking about the image in the central premise of the exhibition: the juxtaposition of historical optical apparatuses from the Werner Nekes collection, with works by contemporary artists.

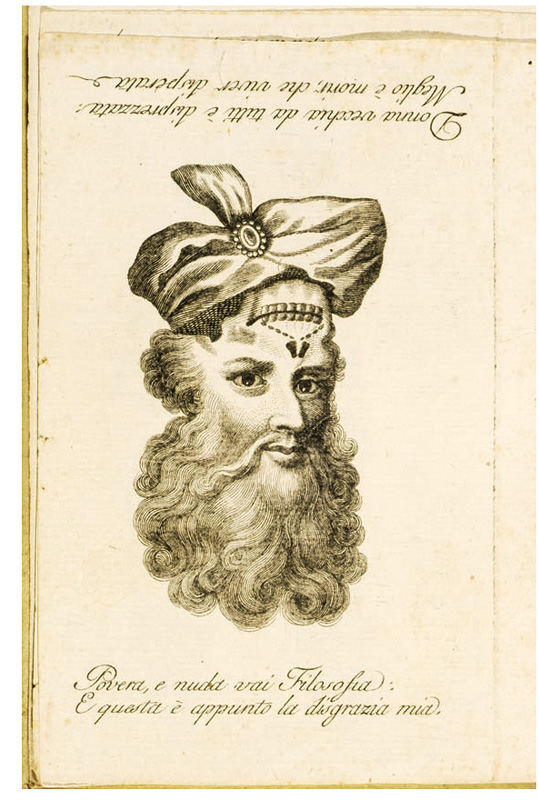

Werner Nekes, a German experimental filmmaker and creator of the Media Magica documentary cycle on the pre-history of cinema, allowed over 200 items from his unique collection to be shown in the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville. Here we could trace the evolution of the manifold techniques of representation from before the birth of cinema. There was a wide array of devices exhibited: laterna magica devices, Dutch camerae obscurae, anamorphoses, 19th century kaleidoscopes, phenakistoscopes (a simple optical apparatus with successive movement phases drawn onto a circular surface), early daguerreotypes, historic zoetropes (a drum shaped device using a paper tape with a sequence of images inside), and stereoscopes. Stereoscopy is any technique allowing the viewing of images in three dimensions, based on the observation that in the case of binocular vision, the visual field of the left eye does not exactly match that of the right eye; in the 19th century, stereoscopes were used to look at pairs of photographs, slightly different from one another, creating an illusion of depth in the picture. The curators also showed charts from perspective treatises, prints by Abraham Bosse, Albrecht Dürer’s engravings, and excerpts of Athanasius Kirchner’s Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae. The choice of exhibits allowed the viewer to track the history of linear perspective, the emergence of modern modes of representation, theories of representation, and the general development of science in regards to the processes of vision.

The second part of the exhibition was devoted to modern art. Contemporary artists displayed a very different attitude towards vision and visuality than the authors of historical treatises and the makers of ancient optical apparatuses, criticizing instead the idea of a coherent subject and an impartial model of perceiving reality. Referring to historical knowledge from the field of optics and physics, they tried to question the paradigm of the “objective eye.”

Among the contemporary pieces shown was an optical apparatus constructed by Robert Smithson, who based its structure on the first stereoscope built by Charles Weatstone in the 19th century. Dennis Adams created a flip-book containing successive frames from a short movie directed by Urlike Meinhof: this was to be viewed collectively, distributing it to random passers-by on the street. Other artists also turned their attention towards the charm of historical media: Kara Walker and Regina Silveira were inspired by shadow and puppet theatres, and Giulio Paolini visually re-interpreted renaissance perspective treatises by turning them into visual riddles.

The attempt to explain and interpret the processes of seeing are universal and common to both the ages of technical and digital reproduction. The cameral work by Hans-Peter Feldmann (Zwei Mädchen / The Two Girls, 1999) can be read as a metaphor for the twofold status of the image and its problematic and untrustworthy quality in today’s reality, which is dominated by the visual. In the photograph by Feldmann, two little girls meet. Although both of them cast shadows, suggesting an existence in the physical realm, the girls’ dialogue cannot be fulfilled as they inhabit different planes of existence. Hans-Peter Felsmann’s work invites us to reflect on materiality and immateriality of the images and reminds us of John Berger’s reflections on the ontological status of photography.

In About Looking John Berger wonders, “What substituted photography before the camera was invented? One can answer: etchings, drawings, painting. But a more satisfying answer would be memory. The creation and remembrance of the space around us, what was previously the domain of thought, is now the task of photography.”(John Berger, Ways of Seeing (New York: Viking Press, 1973).) Berger notes that human vision is not only a question of physiology, but the interpretation of images is also influenced by our memory and experience.

Blickmaschinen suggested a very dense relationship between art and technology. The curators decided to present exhibits we would normally associate with science museums. But the well considered choice of objects on the exhibition allowed the viewer to compare and contrast pre-modern and post-modern attitudes towards the problem of vision and visuality. Apart from rendering accessible almost all of the most important themes connected to the science of representation and the status of images, the other advantage of the exhibition was the interactivity of some of the features, which definitely broke with the sterile, “white cube” model of a typical museum institution. The viewers had the unique opportunity to view original optical apparatuses and writings with sufficient explanation to provide the particular background, historical meaning, and importance of each of the scientific approaches to the “world as an image.”

The contrast built by the Blickmaschinen curators between the contemporary and historical attitudes towards the visual, allows us to draw some conclusions about our present era of digital reproduction. Today there are no coherent subjects, and notions of memory and experience, or copies and originals, or representations and their subjects, are perpetually conflated. Perhaps the most significant feature of the exhibition is the permission it gave for technological objects to access institutions usually connected to so–called “high art,” and the equalization of both the discourses of art history and those of visual culture.

Thanks to this particular approach, viewers could experience a broad overview of the history of the dependence of art on technology. The blending of art history with manifold methodological approaches, visualized in this exhibition, makes spectators realize how interdependent they both are.