Vision and Communism at The Smart Museum (Exhibition Review)

The Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, September 29, 2011-January 22, 2012

Upon entering the exhibition Vision and Communism, the viewer is purposefully presented with little information about the Soviet artist and designer Viktor Koretsky (1909- 1998). The almost ninety examples of Koretsky’s work on display make up the largest show featuring this artist in America to date, and include lithographic print posters, mixed-media maquettes, and black-and-white photographs. The exhibition is framed by both its enigmatic title and in the exhibition space itself so that Koretsky’s visually arresting work makes maximum visual impact.

While the pieces are not accompanied by a wealth of didactic information, a text placed at both the entrance and exit of the exhibition position his work between two opposing quotes on the subject of world communism, opening a dialectical space between the violent, repressive reality of a communist regime, and an indictment of the West in its indifference to the oppressive policy of apartheid in South Africa. Alexander Solzhenitsyn decries the “infection” of communism in the world’s organism, while Nelson Mandela identifies communists as “the only group in South Africa who were prepared to treat Africans as human beings.” Armed with these succinct textual excerpts, the viewer is prepared to encounter Koretsky’s politically charged work between these two, quite diametrically opposed, political poles.

Chronologically picking up where the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition Windows on the War: Soviet TASS Posters at Home and Abroad, 1941-1945 left off, this show features Koretsky’s post-World War II poster art, which has remained largely unseen in America. The images on display, produced through the height of the Cold War, feature a range of images of violent Western capitalist oppression during the American Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, and visions of interracial peace and fraternity. The first display features the work Africa Fights, Africa Will Win! (Afrika boretsia, Africa pobedit!, 1971), the now emblematic image of the exhibition, as a maquette flanked by two printed posters. At the center of this image is an African man, represented as a black-and-white photographic figure superimposed onto a fiery abstract red, orange, and yellow backdrop, who breaks the chains that bind his wrists. This triptych presentation is representative of the curatorial design of the exhibition, which aims to acquaint the viewer with the artistic process at the various stages of production, from the maquette in pencil, gouache and paper on wood board, to the final poster in a multiplicity of prints.

The subsequent posters and small-scale, black-and-white photographs in the opening galleries highlight Koretsky’s distinct use of the visual language of capitalist repression, such as the KKK cowl mimicked in the shape of an atomic bomb in Twins in Spirit and Blood (Bliznitsy po dukhu i krovi, 1960s-1980s). Likewise, the dollar sign (repeated throughout much of Koretsky’s work) is depicted as a noose around the neck of a young black man in Justice American-Style (Sud po-amerikanski, ca. 1970s).

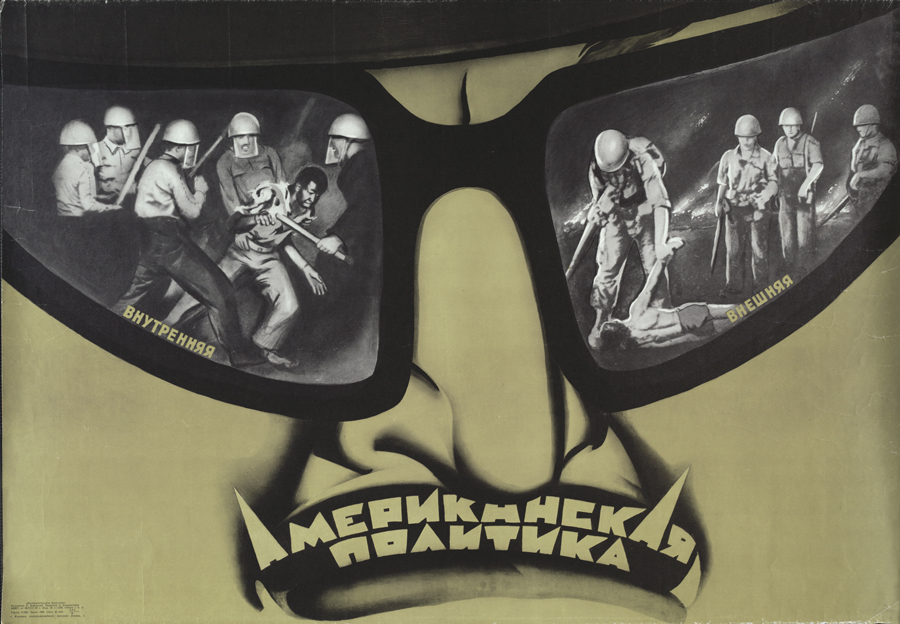

Vision, and particularly the mediation of vision, is thematically underscored in carefully selected pieces, including American Policy (Internal/External) (Amerikanskaia politika (vnutrenniaia/vneshniaia), 1970), in which American internal and external policies are rendered into vision itself as the reflections in the manically turned-up glasses of the American bureaucrat. In America’s Shame (Pozor Ameriki,1968), a red pool of blood flowing from the body of a black youth becomes the lens through which we view the New York skyline. Striking a balance between movement and static iconic imagery, experienced in a repetition of form – again, from the photograph to the maquette to the poster — these images elicit a repeated visual confrontation with violent experience that is nearly impossible to ignore.

While the exhibition’s title promises a focus on visual media, the show contains an additional sensory element in its inclusion of protest songs and speeches from South Africa. The disembodied soundtrack, including the voice of Mandela and South AfricanFreedom songs, is alternately aggressive and mournful, much like Koretsky’s anti-apartheid images featured in the central rooms of the exhibition. The collection of Koretsky’s work accompanied by the audio component intensifies the visual and emotional experience of moving from images of repression and violence to the pathos elicited by the faces of orphaned children. The interior room of the show is the epicenter of the musical accompaniment, and also the reflective central space of the exhibition. Featured here are comparative timelines of the Civil Rights Movement in America, major events in communism in the Soviet Union, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. Coupled with Save Us! (Spasi!, 1942), the most famous of Koretsky’s posters from the war picturing a Soviet mother holding her child in a pose reminiscent of the Madonna and Child, as well as textual accompaniment for the music, this space fleshes out a historical context and background for Koretsky’s images. A small binder invites readers to answer: “How do you personally react to the images today?”

The final section of the exhibition transitions from indictments of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War to images of hopeful socialist peace. The music fades, and the walls reflect positive images of internationalism, and ethnic and racial equality in cool blue and gray hues – a contrast to the beating reds of the preceding images of violence. Images of the hands of aggressors and victims are united as they hold up the next generation of citizens of world communism, as visually represented in the multi-ethnic The Fate of Peace is in the People’s Hands (Delo mir v rukakh narodov!, 1973). This transition is not a chronological reflection of Koretsky’s work, but rather a thematic curatorial choice. The viewer leaves not with the agitation or call to action suggested in the images of violence, but with softening utopic images of children. These final posters are far more static and cool, and perhaps somewhat flat in comparison to the images in the majority of the exhibition, but a seemingly necessary antidote to the death and brutality featured in Korestsky’s politically incendiary images.

The end of the show is also framed with the opposing quotations by Mandela and Solzhenitsyn, along with a small-scale, untitled maquette painting by Koretsky from the 1950s of a Russian-Soviet family in front of a television on which nothing is visible. It is an enigmatic ending to the exhibition, and seems to open almost endless lines of interpretation. Initially Untitled, featuring a domestic interior, seems to lack any political charge. But here, the blank screen of the television invites contemplation of the power of Koretsky’s propaganda images and the audience at which they were aimed: the Soviet citizen at home. The accessible domestic scene also seems primed to superimpose the images as we have just experienced them in the exhibition, images which are largely of our own cultural heritage as Americans. The television, a visual presence in the Soviet home as well as in the United States, reminds us of the possibility of proliferation of the propaganda image into our everyday lives. This exhibition, reflecting the complexities of a conceptual union between vision and communism, visually confronts us with the fact that the propaganda image, infinitely reproducible in various forms – photograph, poster print, and on television – saturated not only the Soviet viewer, but also those in the West.

Back on the street, the potentiality for a veritable explosion of meaning is embodied in the “advertisements” for the exhibition planted throughout Chicago. In select locations, Koretsky’s Africa Fights, Africa Will Win! is plastered on billboards across the city’s urban landscape. According to Matthew Jesse Jackson, a co-curator of Vision and Communism, the idea for the installation of the billboards, as well as the show’s title, predate the exhibition concept itself. An account of the billboard project by John Spelman and Abbey Shaine Dubin will be published in a future issue of Shifter.(See John Spelman in “Our Literal Speed,” Shifter, no. 18 (2012). Forthcoming. ) The following excerpt from their forthcoming interview illuminates the origin of the installation project of Koretsky’s powerful images:

JS: I wanted to put up billboards across Chicago [looks up and points at billboard] that show a black man breaking out of his chains in a distressed landscape.

ASD [looking up, somewhat bemused]: Well, it looks like you got what you wanted. Looks a lot like a movie poster too. Like a Paul Robeson Emperor Jones-type of thing.

JS: I suppose, now that I think about it, it’s a kind of a subliminal message about Obama, the South Side of Chicago, Africa, 2011, all of that. You know: like, hey, native son of the South Side, grandson of Africa, break out of the capitalist chains, return to the vision…

Placed within an American cultural landscape, Koretsky’s black man breaking from bondage enters a new visual and cultural space. Spelman’s project transforms the image into a kind of advertisement, paradoxical for Koretsky’s work that offered an alternative to capitalist advertising culture. Spelman notes that the leaflet-size posters advertising Vision and Communism also showed up at the Occupy Chicago movement, where protesters wrote their own slogan (“We are the 99%”) across the image. While public space seems to have muddled the origins of the message, its enduring impact reflects the visual strength of Koretsky’s work, brought to Chicago in large part due to Spelman’s initial interest in Koretsky, and in conjunction with Chicago’s current Soviet Arts Experience, a citywide festival of Soviet art and culture. With Vision and Communism, the Smart Museum and joint curators have made a substantial contribution to the discursive space of the Soviet Arts Experience, highlighting Koretsky’s immense contribution to post-war Soviet graphic art, while also raising essential questions about the mediation of the image at large.