Urban Landscapes: National Imagery and Its Present Day Articulations

In this short essay I intend to investigate certain representational images and architectural articulations of the present-day Ukraine. By doing so, I attempt to critique the practice of architecture in a specific manner.

Recognizing architecture’s commitment to represent an invisible “reality,” which stays behind the object of representation, and architecture’s role in building up the “collective memory” – one’s reenactment into the life of community, city, nation or country, I decided to explore the ways the social space and the scope of national imagery is set into a work of architecture.

Several reasons influenced my decision. First, let’s agree that architecture, as a built environment, is the most public among arts, and at the same time appears to be a constellation of the reality principle.

Second, current debate on finding a consensus and solidarity across national, religious, and gender issues, has become particularly tough during the on-going election campaign.

And, finally, the fact is that today’s discussion on urbanism develops along at least two mainstream lines: the homogenizing one that presupposes strategies of erasing the differences and embracing citizens into a new fabricated real and imaginary social totality; and the line of emphasizing privacy, which recognizes the differences, enabling them to function as clusters or autonomous group identities – be it national, cultural, ethnic or sexual minorities.

And, finally, the fact is that today’s discussion on urbanism develops along at least two mainstream lines: the homogenizing one that presupposes strategies of erasing the differences and embracing citizens into a new fabricated real and imaginary social totality; and the line of emphasizing privacy, which recognizes the differences, enabling them to function as clusters or autonomous group identities – be it national, cultural, ethnic or sexual minorities.

Attempting to re-define a sense of national identity in today’s Ukraine, which sometimes has to bear uneven political and ideological realities by imposing an institutional frame of the revised version of national culture and history, goes hand in hand with the re-conceptualization of other aspects of identity as well, since national identities are interlaced with gender, religious or locally formed concepts of the self and society.

If nothing else, focusing on the contemporary practices of historic preservation and conservation provides us with possibilities to examine nationalist discourses, stereotypic visions, their dissemination and articulation: practices of visualizing ideas and “normative” views that are used to construct and to “center” a “national ideology” – a concrete system on which moral, political or social foundations could or are intended to stand.

Architecture and theory always deployed history, or to be more precise – interpretations of history. Urban memory was supposed to “cast” certain historical narratives in the forms of “monumental architecture,” in a way, quite similar to the Nietzschean concept of “monumental history.”(It is important to note that contemporary Ukrainian practices of historic preservation and most of the recent urban renovations still operate within the “visualizing history” model thus having much in common with the well known Alois Riegl’s scheme of classification of monuments, valued in different times and for different reasons. According to Riegl, those values were memorial value as well as historical and of age value. Of course, it is the third one which deals primarily with memory and memories, but the first two “merge” at certain points with the Nietzschean concept of “monumental history.”)

Basically, in popular imagination the question of “our history” becomes a form of what do we expect or want from history and is then used to “explain” or “interpret” our present, using examples from “our own” history. Furthermore, historical representations and interpretations presuppose that these constructions are invested with a certain aura of authenticity.

Such a view, however, must not go unchallenged, since even instrumental and “transformational” modes of “quoting history” are not free from certain intentions, or interests, that, in turn, give place to ideological implications.

Take for instance the still “hot” question of tackling the Soviet past. Is it possible to “reconcile” at least two different perspectives of Ukrainian history (“colonial”, or more strictly – Russian-centered and post-colonial Ukrainian-centered) into a more or less “coherent” historical narrative? How could we bring together those who wish to forget or ignore and those who insist on remembering? And should we?

On the one hand, these two value systems seem virtually “incompatible”. On the other hand, there are several millions of people whose lives and private memories are tightly connected with the Soviet era. It is these people who become subject to political manipulations.

Thus, to build up an “imagined community” of their own, post-colonial societies are to re-invent a self-image: we witness the conceptual shift in myths and ideologies, social and political configurations. Consequently, a set of symbolic systems is being re-designed intentionally and accommodatedto the needs of the new ideology.

Yet the problem of “the use of history” by architecture may be addressed within the context of the more specific terms – which is, architecture and its relation to the social, or put differently, architecture’s capacity to condition certain cultural expectations and responses within the “users.” In short, it is to insert the “potential viewers” into the realm of optical knowledge.

We have to admit that the art of visualizing national imagery into architectural forms resides upon at least two modes: the visionary (or “architecture parlante,” when architectural form itself is intended to generate the effect), and the spatializing one (employing certain disciplinary practices and technologies of projecting the subject in all its invariance into the urban fabric). The human body thus appears as both the “initial” paradigm of order for urbanism and architecture, as well as a “tool” of subjectivity.

Yet it is not just a set of mimetic analogies that makes our world meaningful. But rather, by recognizing architecture’s “allegorical efficacy” to “produce subjects”, or to transform and to “shape” the human body through the new social and cultural environment, the body is “urbanized” and turned into the “metropolitan body.”

But what body? An un-gendered body is an unthinkable one. On one level, architectural theory has always relied upon its “classical topos” or its “strategic reference”- of an impersonal figure of the Perfect Vitruvian Man (sometimes quite apparent or sometimes hidden in an unconscious way).

However, the inscriptions of the body were never innocent or arbitrary. On another level, urban spaces served as an efficient layout for spatializing gender.

The dominant cultural impulse of male dominance is still visible in post-socialist Ukrainian cities, whether in the ‘official’ spaces of power (e.g. parliament or numerous governmental institutions), or the spatial order of a house (“I’ve bought a kitchen for my wife, nursery furniture for my son, and an office equipment for myself”- reads one of the billboard ads).

Male dominance is also present in night-town erotica and spontaneous street markets, where most of the merchants are unemployed women.

It is traceable in shop-windows and sexist advertising (where the female body is reduced to gastro-porno signs particularly, in the practice of employing a “national beauty ideal” and exploiting the standard images of the globalized network, which runs in tandem without apparent contradiction). Or, finally, it is present in numerous monuments and memorials found all over the country.

In recent years new accents in functional zoning have come to existence:. Kyiv has become a capital city, the structural representation of central areas in most cities and towns has undergone certain changes, new institutions have come into life, etc.

Thus the pace of re-figuring city centers has accelerated. Furthermore, we witness a new wave of polarization; political, cultural, property, or ethnic changes have considerably reshaped the spaces of the city.

Attempts to preserve monuments and historic places because they belong to a nation’s patrimony have multiplied. The practice of preservation in most cases has been transformed into the practice of simulation: dozens of replicas of the previously ruined churches appeared all over the country.

Indeed, the policy of historic preservation, reconstruction or conservation, along with urban re-development practices, concerns, first of all, definite aspects of private property (let alone legal and investment policies) or social and political issues.

In our case, we could also speak of religious policies, although this is quite a slippery terrain in today’s Ukraine. On one level, the Church is separated from the State, while on the other level, the State is balancing precariously between five Christian congregations, as well as numerous neo-protestant denominations.

For instance, the reconstructed/or replicated Mykhailivsky Monastery (see fig.) has gone to the Kyiv Patriarchy, while the renovated Uspensky Cathedral was given to the representatives of the Russian Orthodox church.

But the confluence of the official historical narrative or, more precisely, of the institutionalized version of Ukrainian culture and the religious ideology in seeking a consensus on the sense of nationhood, is clearly visible in the gender regime.(However, a question of institutionalizing the, so to speak, Ukraine-centered perspective on religious policy deserves special consideration.)

To be sure, the patriarchal values, as a kind of an underpinning motif, become an overlapping area, a discursive terrain where both ideologies meet to “secure” individual self and national identity.

Next, we have to keep in mind that almost 90% of national heritage, whatever we understand by that term, has disappeared in the course of historical collisions, from the Mongol invasion to the Bolsheviks’ times.

These upheavals of Ukrainian history (let alone the 20th century revolutions, communist repression, famine, wars, armed conflicts and finally Chernobyl) find their representations in practices of commemoration and become manifest in urban and village landscapes.

From the end of the 1980s, there appeared memorials representing a succession of death, suffering, and destruction as markers of disrupted and conflict-ridden historical narratives.

|

The painful process of undoing the colonial and Soviet past seemed to sound and make manifest the personal and collective trauma, thus a sense of traumatized consciousness hovers over the official historical narrative and its representations (e.g. Afghan Veteran Memorial, a memorial to the victims of the Famine of 1932-33; Babi Yar Memorial or a memorial to the soccer players of the so-called Match of Death, Dynamo-Kyiv vs. Germany team ; or, finally, a memorial to the victims of Stalinist repression in Bykivnia).

Of course, this essay is just a sketch of what I have in mind, but could indicate directions toward which to proceed, and questions to ask of spaces, identities, and power representations or their contemporary appropriations.

My references are, for instance: to housing policy and articulations of the modernist concept of transparency during the Soviet regime, to an unprecedented “transformational” project aimed to “breed” camouflaging Soviet identity, and to still highly politicized urban landscapes, or monuments that were to serve as extensive propaganda tools rather than the ideal of immortalization.

Here one could also think of Ukraine as mostly a rural, traditional culture, of its staying apart from the urban tradition of subordinated spaces, not to mention the striking uniformity of the Soviet city centers–similar-looking gloom-colored apartment blocks with standard cells–of the nearly eliminated sense of privacy and of the politics of demolition of architectural monuments in the past.

Basically, architectural mechanisms of public surveillance relied upon the palpable spatial identity of the controlling institution – were it a school, a factory, a block of apartments, a work-place, or a community center (in Soviet terminology – budynok kultury).

This surveillance, in turn, contributed to the loss of any distinction between public and private, forcing individuals to dissolve into and to assimilate with the milieu. In this perspective, the practice of adding “national flair” (ornaments, columns, etc.) to the appearance of buildings could be regarded as just local “exotic” alternations made to the already ideologically defined structures.

A move to “justify” the independent Ukrainian state has found its ultimate embodiment or “actual form” in the idea of re-fashioning the Independence Square and there erecting a monument to Independence.

|  |

Known as a Goat’s swamp in the early 19th century the site was engulfed by city expansion and has since included plans of urban development. In the early 1980s, it became the central square of the city, named October Revolution Square, with a huge statue of Lenin on display.

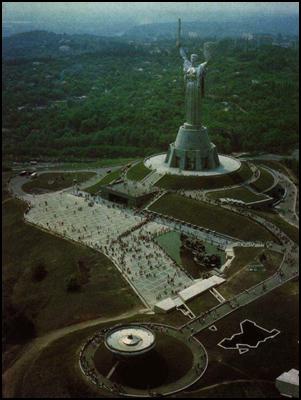

Almost simultaneously, on the hills overlooking the Dnipro River another ensemble arose commemorating the victory in the World War II or the Great Patriotic War as it is still named in official discourse. The museum building was conceived to serve as a pedestal to a giant allegorical figure of a woman warrior; symbolizing “Mother of the Homeland,” “Rodina Mat” (such mythological images are found elsewhere from Moscow to Berlin).

|

Popular imagination reacted immediately. The museum was labeled “a museum under a woman’s skirt,” and the statue obtained the nickname of Iron Lady or Iron Maiden, a name preferred by the young generation, or simply “baba” (a derogatory word for either a peasant woman or any adult female).

The negative connotations came from the oppressive and impoverished surroundings in which women lived, restricted to the house, the husband, and the state.

This Iron Lady still hovers over the city and neighboring areas of the gold-capped domes of the Kievo-Pechersk monastery and has become an ugly landmark in the cityscape.(Some kids were reported to scream with horror on seeing this “beautiful” lady-monument.) Moreover, the statue could be regarded as a symbolic counterpoise – and at the same time complimentary reference to the newly erected monument to Independence (see fig.).

Indeed, “the Lenin number 1″(Hundreds, if not thousands, of standard statues of Lenin – an iconic figure of socialism – still tower in the central squares of the cities and towns. However in August 1991 the Lenin monuments became the targets of anti-Soviet stance, but shortly after in many places they were carefully washed and renovated. It is quite important to note that drastic changes to monuments and some street names occurred mostly in cities, not in rural areas. Moreover, changes affected mostly Western parts of the country; for instance, a huge statue of Lenin in Kharkiv (which is in Eastern Ukraine) remains untouched.) (see fig.) was among the first targets in August 1991. Yet, this quick removal was in a way a symbolic gesture or coup de force; something like the storming of the Bastille as an embodiment of Ancient Regime during the French Revolution in the 18th century. Even in its strange and somewhat comical afterlife, the square has not lost its political connotations.

But its symbolic dimension seemed to change radically. First, in the place once occupied by Lenin, there appeared the advertisements for banks and luxury goods; signs of incoming globalization, images of the yet unknown, but nevertheless, desired culture of consumerism.

Meanwhile, the idea of erecting a new monument continued to haunt the head officials.(In this context, an intrigue that accompanied a quasi-competition and the commissioning of the monument itself deserves special consideration. Suffice it to say that the “fate” of the monument was determined in 1995 – long before the last stage of the so-called competition took place.) Finally, Anatol Kushch, one of those close to the official circle’s sculptors, received the commission, and erected a column crowned with the allegorical figure of a woman as the embodiment of the nascent Ukrainian State.

Initially conceived as an ever-young virgin, the statue acquired the look of a middle-aged woman, symbolizing all her possible roles or “hypostasis”: daughter, sister, mother and wife.

The reason for such a metamorphosis was “simple to the point of absurdity,” the phrase coined by the Kyiv mayor. Furthermore, beneath the column a quasi-pantheon of national heroes embracing a thousand years of the Ukrainian history is still being built.

Yet, the question of “inclusion/exclusion” remains unclear. Here we see that the author tries to operate in a weighty symbolic dimension, which is quite problematic since monuments, regarded in terms of “pure” symbolism, would hardly find an “adequate reaction” in today’s world. Here comes to mind another “liberating project”: Christo’s wrapping of the Reichstag in 1995.

Alongside other associations, the primary focus of the project was detracting from the symbolic value of the building through the catharsis of “wrapping”. Thus having lost its symbolic “status” or aura of the edge of the island city, Reichstag became a bustling place of politicians and a center of democracy.(See B. Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 83-97.)

In this light, our Monument to Independence could be regarded as a kind of longing for “normalcy” or for a metaphysical presence of meaning, while Christo’s project appears as a recognizable shape and a ghostly apparition of the German past.

An array of interpretations of Ukrainian history finds its place in the repertoire of contemporary cultural effects, whether commercially and “ideologically” useful or state-sponsored.

In our case, the move to preserve monuments and historic places as national heritage appears as the search of representational models that are grounded primarily in the nation’s past, the basis for our urban efforts.

But in trying to represent them we have to make sure that the proposed set of images or symbols – visualized national metaphors – is shared and understood by the community.

Put differently, the operation of representation presupposes that this “message” has to be related symbolically to the nation’s collective identity.

Moreover, it is intended to demonstrate a unity and collective will of the imaginary ideal citizens. Hence, in this perspective we would need not only a “model” of a “handed down” collective past, but also a model of an “ideal citizen.” It is here, that several questions arise.

First, we have to ask ourselves: do we really have an idea of what these “models” should look like?

Then, are we sure that the “message” would be “understood correctly”? In other words, do we have a community with a strong feeling of collective identity that will “ground” our understanding?

We also have to question the way the model of a “collective past” is constructed, handed down and articulated.