Unbuild Together: The Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale

Curated by Lesley Lokko, the 18th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennial is titled The Laboratory of the Future, and this concept serves as the underlying theme for the central exhibitions in the Giardini and Arsenale, as well as the national pavilions scattered through Venice’s six sestieri. Where the biennale at large provided a spotlight on Africa and the African Diaspora, each of the national pavilions individually returned to the language of “the experiment” to consider possible futures. Often contrasting past and present, as in the case of the Uzbekistan pavilion, this language of experimentation and possibility similarly appeared sporadically throughout the city. As the sole pavilion by a Central Asian nation, the Uzbek pavilion on the Arsenale stands out due to its location alongside its neighbors—the Chinese and Italian pavilions, two of the largest spaces in terms of sheer size. With the absence of representation at the Russian pavilion, and the relegation of Georgia and Kuwait to venues outside of both the Arsenale and Giardini, the Uzbek pavilion constitutes the sole voice for the region among the globe-spanning delegations from over sixty nations at the biennial. While some commissions read the “laboratory” theme through the evocation of atemporal utopias, other pavilions (such as the Uzbek one) looked instead to the past—seeking to contemplate how the past provides avenues for constructing the future.

Studio KO, Unbuild Together, exhibition view, Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo: Nicolay Duque-Robayo.

These explorations of the horizon of the past took two forms: gestures toward specific historical moments, or contemporary attempts to envision a better tomorrow. The Romanian pavilion, for example—curated by Emil lvănescu and Simina Filat—engaged the first mode of future reflection, showcasing the historical achievements of architectural and artistic practitioners who envisioned progress in their respective time periods. The Ukrainian project, Before the Future, contends with the paradoxical condition of narrating for the future amidst contemporary armed conflict on the ground. Straddling the two approaches, the Ukrainian Pavilion was uniquely showcased in both the Giardini and Arsenale. Following the latter of the two models, the Uzbek pavilion Unbuild Together: Archaism vs Modernity challenged the tensions between the concepts identified in its subtitle by considering Uzbek architectural heritage as itself a contemporary vehicle for speculating potential futures. Rather than imposing a contrast between a vernacular practice relegated to the past and a technocratic present where architectural education and practice largely occurs on a computer screen, the pavilion’s curators center the construction brick as both a physical material and a site of study. The curators also foreground the importance of design pedagogy to establishing a pool of future practitioners—now students—who will work directly in establishing new relationships between materials, structures, and histories.

Located on the northern most end of the Arsenale, Uzbekistan’s contribution to the 2023 Architecture Biennale attracts its visitors with a mirrored entrance. Curated by Studio KO, a Paris and Marrakech-based architecture firm, the pavilion’s sparse spotlighting lures its guests deeper into the darkened corridors of Unbuild Together—an experience guided by contrast and curiosity. Studio KO’s portfolio largely consists of luxury residential and commercial projects in France and Morocco. Recently commissioned to design the Center for Contemporary Arts in Uzbekistan, located in the capital of Tashkent, the most prominent cultural project that Studio KO previously completed was the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakech. Thus, the invitation from the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, the commissioner of this year’s pavilion, expands the studio’s cultural work while also providing the stage of the national pavilion in Venice.

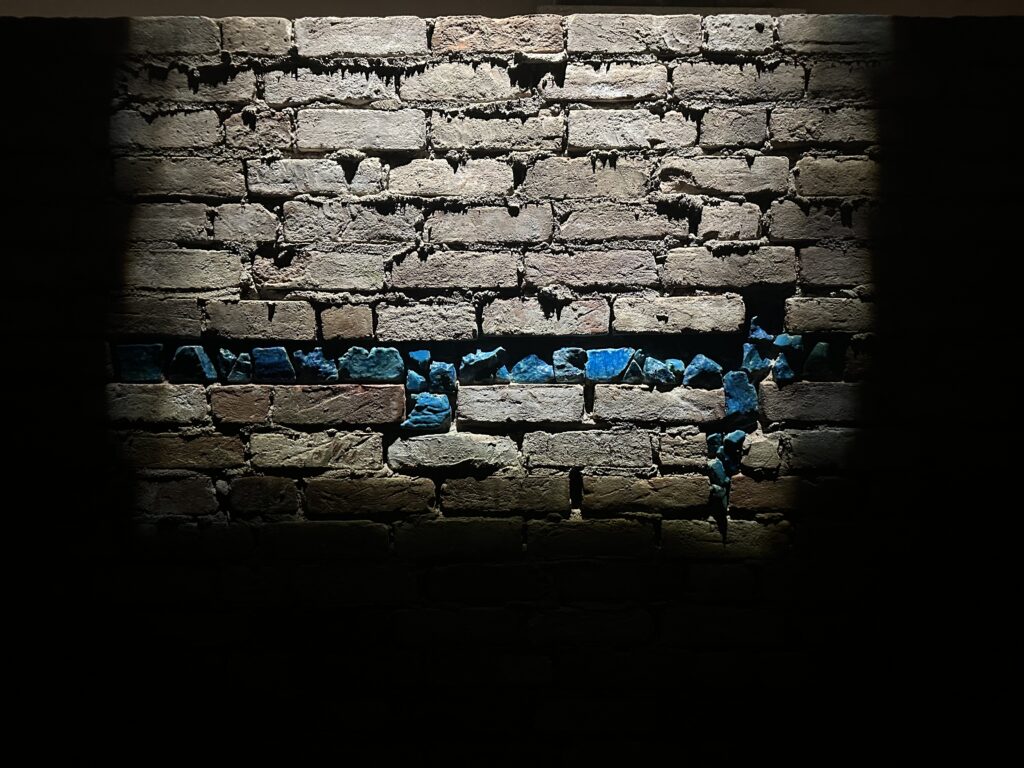

Upon reaching the center of the Uzbek pavilion, visitors encounter a labyrinth built from recycled terracotta bricks. Studio KO founders Karl Fournier and Olivier Marty explain their design choices in the wall text: “Made of bricks salvaged from Venetian construction sites and scattered with glazed Uzbek terracotta fragments, this architectural installation revisits temporal and spatial limits, establishes unexpected bridges between eras and tries to deconstruct, unbuild, the opposition between archaism and modernity.” The materiality of the structure is doubly reinforced by the sensorial: the smell of earth filling the air, and the unavoidable confrontation with the walls’ tactility as one navigates the shadowy space.

Studio KO, Unbuild Together, exhibition view, Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo: Nicolay Duque-Robayo.

In collaboration with architecture students from the Ajou University in Tashkent, two workshops led by Studio KO served as studies for the Uzbek pavilion. The first workshop approached the theoretical value of contrasting the notion of modernity with the notion of context, constituting the potential for the future and for history, respectively. By foregrounding the pedagogical process of reading historical texts, along with seminar discussions, this first workshop served as a platform for the students to consider the values and assumed knowledge that go into architectural practice. It was at this stage of the project that the labyrinth model emerged, as an architectural structure that abstracts the untangling of history. The second workshop, titled Brick, from Clay to Wall, turned to the brick as a local site of investigation. Taking place in the city of Bukhara, whose historic center is listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the workshop was led by local ceramicist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy and was centered on testing local materials and glazing techniques traditional to the region. The efforts of the second workshop are represented in the Arsenale pavilion with a set of “traces and relics” collected by the students. Notebooks, test materials, sketches, rocks, and cellphones occupy a glass vitrine near the back of the room. The remnants point to both the pedagogical value of the workshop and its tethering to Uzbekistan. A temporal dislocation between traditional techniques and the smartphones used by students to document the workshop folds together the practice of architecture as informed by its historical and geographical context.

Throughout the labyrinth structure, lights were directed to several glazed bricks produced in the second workshop. Embedded within the walls, these bricks stand out visually from the surrounding terracotta, but their materiality also emphasizes tactility—the alluring blue glaze is both delicate and rigid to the touch. The glazed bricks adorned corners of the unpredictable turns of the maze, as well as a few points of entry into the structure. Yet this contrast between the bricks was not just visual and material. Importantly, the glazed bricks were sourced from Uzbekistan, marking physical and narrative contrast with the unglazed Venetian terracotta bricks that constitute much of the structure. Evoking both the playful confusion of a puzzle and the material anchor of the pavilion, the labyrinthine design oscillates between commonly accepted dualities: Venice/Bukhara; Past/Future; Signifier/Signified; Archaism/Modernity.

Studio KO, Unbuild Together, exhibition view, Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo: Nicolay Duque-Robayo.

This tension between past and future present in Venice is but an echo of the unique historical position in which Bukhara is situated. “The calm of the airport is mirrored in the opposite side of the city littered by mountains of iron scrap, cranes rusted under the sun, vacant industrial sheds, and railways abandoned by their locomotives. These monuments speak to the collapse of a Soviet economy,” writes Attilio Petruccioli for the proceedings of a 1996 conference on the architectural legacy of the city. “Buttressed by scaffoldings and signs of construction in preparation for the celebration of the 2500th anniversary of Bukhara, they are revitalizing her ancient splendor with bright new tiles.”(Antonio Petruccioli, “Introduction,” in Bukhara: The Myth and the Architecture (Cambridge, Mass: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1999), p. 9.) Petroccioli’s remarks contrast the field work he conducted since Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991, suggesting the many comparative temporalities the nation engages with when embarking in historical projects. To engage with an abstract form of “archaism” invites another line of inquiry: when does the past begin and end? Which definition of modernity is employed here? How does one temporally bracket the contemporary? When engaging in the traditional forms of making and building in Bukhara, Studio KO pretends to evoke a specific time frame: an undated period of antiquity that lacks a reference to the Soviet socialist period of the twentieth century. This omission, perhaps deliberate considering its lingering historical echo and the current conflict in Ukraine, is not a form of historical amnesia or erasure of recent past. Rather, by further underscoring the temporal distance, “antiquity” in Studio KO’s archaism refers to a past where historical marks are traced within the techniques of construction rather than a historical record. This nebulous black box, an undated period of time, poses as many questions as the exhibition proposes to answer. As the sole Central Asian nation represented at the Biennale, and one of the few delegations that can speak to a post-Soviet condition in the Arsenale, the unique position of the Uzbekistan pavilion posits an inquiry into any nation’s historical past, without decisively singling out that nation’s own specific twentieth-century history.

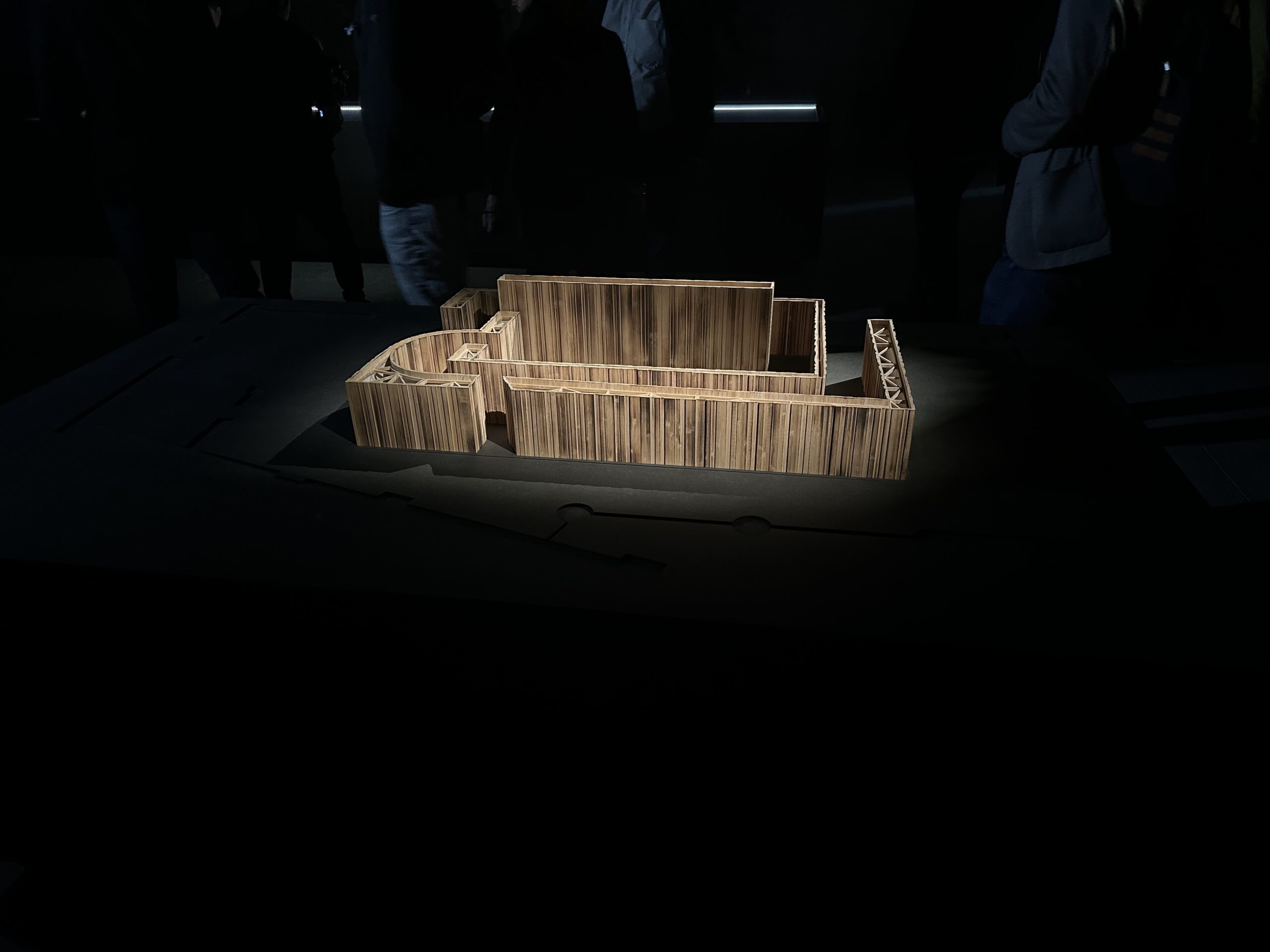

Through the two workshop collaborations with the Ajou University students, the pedagogical component of the exhibition provides an avenue for defining a tangible outcome to the dialectical project of Studio KO. Near the collection of workshop ephemera in the rear of the pavilion, a 1:20 scale model of the labyrinth built out of fire-blackened bamboo sits illuminated by a sole spotlight. By emphasizing the points of entry and exit into the structured housed within the pavilion, the model circumvents a didactic reading of the labyrinth as an intellectual challenge ruled by two opposing forces: that of entry and exit. Alluding to the firing process that produces the glaze, the fire-blackened model reaffirms the materiality of the site and its design process as central to the larger project of envisioning new futures. Rather than providing a deterministic vision of what results from reflecting on history, Studio KO proposes that there are as many points of entry as possible outcomes. The involvement of university students—architecture professionals to-be—places this visioning project in the hands of those future generations who will build anew in Uzbekistan. It places the construction of the future vis-à-vis the continuation of historical practices, rejecting the delusions of modernism that contend better futures involve disposing of the past. Although rhetorically moving, this proposal by the pavilion curators runs the danger of displacing immediate action today by imposing the responsibility to future generations.

Studio KO, Unbuild Together, exhibition view, Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo: Nicolay Duque-Robayo.

Along the center of the labyrinth, a six-minute video by artist El Mehdi Azzam projects onto one of the bricked walls of the structure. Filmed during the two workshops, the video captures scenes of discussion and work among participants, “freez[ing] the moment in time,” as noted on the wall text of the pavilion. Devoid of a clear narrative, the film collages the events leading up to the production of the pavilion and reactivates the involvement of the students by embedding their work back into the structure. This projection once again inscribes the role of emerging professionals and fresh perspectives into the project of a future Uzbekistan: actively engaged in the history project to build a new future. Azzam’s film further underscores the value of process in the pedagogical framing of architecture, where multiple agents leave marks on the final outcome of any given project. Rendering neither an apocalyptic dystopian future nor an idyllic utopia, Studio KO responds to the call for the “laboratory of the future” by focusing on the process of production rather than what a specific future—for Uzbekistan, for the built environment, or for the discipline of architecture—ought to look like. It advocates instead that responsible practitioners should be attentive to histories and methods of the region to understand and build anew.

But which pasts, which histories and methods, are deemed worthy to address in the visioning of a future? The absence of Uzbekistan’s recent Soviet past is a significant omission by the curatorial team. This oversight neither prescribes historical revisionism, nor does it sympathize with a call for all post-Soviet nations to constantly engage with their twentieth-century legacies in every contemporary project. But when embarking on a project in which the central argument contrasts the past with the present towards an understanding of a possible national future, any omission in terms of which histories are available to be learned from raises skepticism about the nature of the inquiry. Ultimately—with pedagogical and curatorial projects alike—to look back in history requires a critical attention to the historical record. The absence of such a critical relation to both history and historiography runs the danger of evoking the same silences and omissions that dogmatic canons have historically perpetuated, often in regions outside Western Europe and North America. Methods and techniques used today will presumably one day fall under the category of “archaic.” If there is an imperative to preserve the traditions of an archaic past, what are the destinies of the tools of the not-so-distant past: is the responsibility for grappling with these histories displaced to future generations? Does this constitute an erasure, or a covering up? Perhaps the case of the Uzbekistan pavilion avoids these questions in favor of trying to carve out a space of advocacy: a space where histories beyond the Soviet legacy can be more readily recovered in the present moment.

Studio KO, Unbuild Together, exhibition view, Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo: Nicolay Duque-Robayo.

With an optimistic tone, the Uzbek pavilion asks the audience to believe in the intellectual and context-driven rigor with which the current generation of architecture students are trained. The strength of Uzbekistan’s presentation of Unbuild Together ultimately rests on its embrace of alternative methods for the biennial’s “laboratory of the future,” and its rejection of a singular vision for designing “tomorrow.” Lesley Lokko’s call for the importance of architectural exhibitions comes to the fore in Studio KO’s contribution: “[exhibitions] are a unique moment in which to augment, change, or re-tell a story, whose audience and impact is felt far beyond the physical walls and spaces that hold it. What we say publicly matters because it is the ground on which change is built, in tiny increments as well as giant leaps.”(Lesley Lokko, “Introduction,” Biennale Architettura 2023, La Biennale di Venezia, accessed June 16, 2023, https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2023/introduction-lesley-lokko.) Pedagogical training is thus pivotal to the project housed in the Uzbek pavilion. While centered around the contributions of the students from Ajou University, the curatorial team ultimately invites the visitors of to the pavilion—albeit passively as mere spectators—to grapple with the dualities presented and challenged within the labyrinth, within the building materials themselves. Where the engagement on behalf of the visitors to the pavilion is limited to experiencing the tactility of the labyrinth, didactic labels, and the video, Studio KO argues that it is in the hands of young practitioners on the ground that a contrasting, better future will ultimately take form.

“Unbuilding” “together” from the distance of Venice is itself an exploratory process rather than a clearly defined objective; and unbuilding together as a process requires multiple parties, perspectives, and methods, theoretically and pragmatically. This dislocation affirms the unique contribution of the Uzbekistan pavilion to the 18th Venice Architecture Biennial not just as a representative of the Central Asian region, but also its presentation of a pedagogical model that external audiences can evaluate vis-à-vis the pavilion in Venice. To dismantle in order to build the future challenges linearity and the solution-oriented discipline of architecture as well. The juxtaposition in tactility between the Venetian terracotta and glazed Uzbek brick materializes the possibility of holding contrasting objects, and contrasting narratives, in one space—not oppositional, but as the building blocks of a future yet to come.