Ukrainian Modernism: Identity, Nationhood, Then and Now

The following is a transcription of “Ukrainian Modernism: Identity, Nationhood, Then and Now,” a panel discussion organized by and held at the Chicago Cultural Center in conjunction with the exhibition Crossroads: Modernism in Ukraine, 1910-1930, on view at the Chicago Cultural Center, July 22-October 15, 2006, and The Ukrainian Museum, New York, November 5, 2006-April 29, 2007. The panel focused on the issues raised by the exhibition, as well as issues of concern to contemporary artists in Ukraine. Each panelist presented a brief statement about this topic, then the editor, Susan Snodgrass, presented the panel with a series of questions before opening the discussion to the audience. Panelists included Adrienne Kochman, Assistant Professor of Art History and Indiana University Northwest; Nicholas Sawicki of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and co-curator or Artists Respond: Ukrainian Art and the Orange Revolution; Myroslava Mudrak of Ohio State University; and Andrew Wachtel of Northwestern University.

Susan Snodgrass: Before I introduce the panelists I want to make some brief comments about modern Ukrainian history for those in the audience who are unfamiliar with Ukraine or with Ukrainian art. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the territory of present-day Ukraine came under the subjugation of Russia to the East and the Austria-Hungarian Empire to the West. Ukraine gained its independence in 1918 after the collapse of the Russian Empire. This freedom was soon lost when its territories were repartitioned in 1921. In 1923, the period known as Ukrainization was instituted under the Russian communist party, which sought to gain widespread support from the Ukrainian intelligencia and peasantry. Ukrainization was thoroughly implemented by the government apparatus as well as by the Ukrainian communist party membership. During this time, Ukrainian language and culture really flourished, and were instrumental in forming the Ukrainian national ideal, which is the subject of this exhibition and panel. Artists search for identity occurred through various modern international movements, some of the most influential being Symbolism, Expressionism, Italian Futurism, and Constructivism, as well as through the creation of schools and movements based on forms, particularly folk-art forms, that were unique to Ukrainian culture. Starting from the early 1930s, Ukrainization was abruptly and bloodily ended under Stalin’s well-known reign of terror that declared such policies “bourgeois.” In art, socialist realism was imposed and Ukrainization policies were undone. Later histories of German then Soviet occupation are, perhaps, better known and span several decades. Ukraine gained its independence in 1991 after the dissolution of the USSR, and new democratic policies were instituted after the Orange Revolution in 2004. (And let us not forget such tragic events as the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl in 1986, the aftermath of which still impacts many aspects of Ukrainian life.)

The dramatic political changes that have occurred throughout Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, as well as Ukraine since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Republic have created a more free but transitional state of uncertainty, spawning an essential questioning of cultural identity. Contemporary art is a reflection of this uncertain time of freedom and immense social change. In an attempt to understand the reality of this shifting paradigm, artists, art historians, cultural critics, and institutions are redefining art’s role in a civil society, expanding its audiences, and creating a critical context that allows for broader fields of interpretation — this exhibition being one example. Adopting the language of the international art world has been one strategy. Equally important has been the need to reclaim the heritage of one’s own art history, correlating the art of the present with the art of the past, in particular those movements that sought universal ideals while asserting the sensibilities of place. The exhibition on view encompasses the years 1910 to 1930, basically the few years before Ukraine gained its independence to the rise and fall of Ukrainization. The panelists are going to discuss various aspects of Ukrainian modernism and, in particular, what role art and artists played in creating national identity. We will also discuss how issues of art, self, and nationhood play out in contemporary Ukrainian culture.

Adrienne Kochman:I want to introduce the panel by focusing on the correlation between national identity and modernism in art history. It emerges in part as an outcome of the Western Enlightenment, overlaid with the Industrial Revolution, the development of a commercial gallery system in the 19th century, and also 19th-century nationalism. To be modern signified progress and the furthering of society through new technologies. This exhibition focuses on modernism and its crossroads. One thing characteristic of the early 20th-century avant-garde was the emergence of local avant-garde activity. This exhibition differs from previous exhibitions of Ukrainian avant-garde art, which have occurred in the last ten years or so in Munich and Zagreb, for example, by focusing on the diversity of those developments. One might look at artists who are working out of Poltava and Kiev, yet others who are working out of Lviv and western Ukraine. This is very characteristic of avant-garde developments throughout Europe. What has happened in the writing of Ukrainian art history and the importance of the role of modernism for it, today and in the post-Soviet period, is an attempt to reclaim an identity that was at times rewritten, misrepresented, or erased. The physical evidence, the pictorial document — the painting itself – was altered so that the artwork could not fit into an understanding of what it was to be modern in art, particularly with respect to the relationship between technique and subject matter, or form and content. Paint, for example, was scraped off the surface to remove brushwork, color and line so as to disfigure the integrity of the image. The artist’s original techniques were no longer apparent and the outcome in the finished product so changed, it could no longer represent an accurate visualization of history. Scholars could not analyze the work of art because the evidence no longer existed. Exhibitions like this are geared towards trying to revive but also rewrite an art history that is a missing piece in the lineage of Ukrainian art.

Modernism in particular, during this period is something that has not been acknowledged for Ukrainian artists by the larger [Western] modernist community. This is probably due to gaps in documentation and the tendency in the West to view Ukrainian modernism through a Russian framework. The connections with Ukrainian history are not always made and the context of having been under a totalitarian regime which tries to erase or reshape what Ukrainian identity is has been under explored. The crossroads theme, as opposed to the theme of the avant-garde, stresses the diversity of modernism in Ukraine. It is actually quite parallel to what we see in the German Empire where avant-garde developments occurred in a number of urban centers such as Munich, the Rhine Valley, Berlin, Dresden. We see a similar phenomenon for Ukraine. The diversification of the arts seems to be a pattern for Ukraine’s artistic development — from Ukraine’s relationship with the Russian Empire, particularly in the 19th century, through its very brief period of early independence, Ukrainization of the 1920s, and even, when possible, during the Soviet period. Having various threads or islands of self-determination was a way to prevent conformism from taking hold everywhere in Ukraine. While it might be seen as something that causes problems today in terms of unification or a unified kind of singular vision, it might also be understood as a way of preserving culture. It represents a defensive posture against an oppressive regime imposing conformity and a linear artificial history as in the Soviet Union — diversifying and scattering artistic roots — makes it much harder to control. Exhibitions like this are the crossroads, this type of cross-section, of what is part of early Ukrainian modern art in the early 20th century; it really suggests that kind of organic development.

Nicholas Sawicki:Adrienne makes a good point. The history of Ukrainian art is replete with erasures. Many of the artists in this show, as said earlier, have traditionally been placed within the category of Russian avant-garde and modern art. This is one of the first exhibitions to recast these individuals as Ukrainian. This raises some basic questions. How are we to understand the terms “Ukrainian modernism” and “modernism in Ukraine”? What permits us to speak of the diversity of artists and works in this show as Ukrainian? Can we speak of a common Ukrainian modern style in their art? Can we speak of Ukrainian themes or subjects? Are these viable criteria for distinguishing a Ukrainian art? Or should we be speaking about artists who consciously identified with a Ukrainian national identity, and who styled themselves in personal and public life as Ukrainian–whatever they understood this to mean?

We’re not going to get to all of these questions tonight, and I’m not sure that I have any answers. But I would like to make a few observations. The first thing is that these paintings date to a twenty-year period between 1910 and 1930 and were produced by over a dozen artists. They are fundamentally diverse in style. There is no shared outward appearance that unifies them. There are some artists here, like Mykhailo Boichuk, who made a deliberate effort to cultivate a Ukrainian style of painting. They modeled their work, in part, on local traditions of religious and folk art, as Susan said. But many artists did not follow this path. Instead, they sought a style that was individual and distinctive to their own work.

David Burliuk, Time, 1910x. 31.5 in. x 25 5/8 in., oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

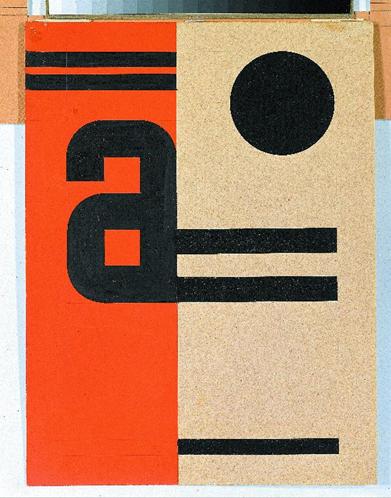

Vasyl Yermilov, Avant Garde, Design for the cover of a journal, 1929. 12 in. x 9 in., gouache and india ink on paper. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

Vsevolod Maksymovych, Fedir Krychevsky, Alexander Archipenko, and Oleksa Novakivsky strike me as good examples. Other artists in the exhibition adapted already existing artistic styles, predominantly from Paris. The paintings of Alexandra Exter, David Burliuk, and the early work of Vasyl Yermilov take Parisian Cubism as a reference point.

Alexandra Exter, Bridge. Sevres, 1912. 57 1/8 in. x 45.25 in., oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

Exter’s exquisite 1912 painting, Bridge, which hangs in the exhibition, would fit quite comfortably alongside the work of a native French painter like Jean Metzinger. Mykhailo Zhuk’s 1914 decorative panel is a virtual facsimile of the style of his Polish teacher Stanislaw Wyspianski.

If we consider subject matter, we’re confronted with similar issues. There are portraits of Ukrainian sitters and landscapes and street scenes from Ukraine. But we also see many paintings that focus on more generic motifs. Many works show no effort to cultivate a specific Ukrainian style or content. And some of the artists would have had little reason to take up such an enterprise. They viewed Ukrainianness as one aspect of their identity, or a minor one. Many viewed themselves as belonging first and foremost to other ethnic and social groups, by birthright or personal decision. A handful of the artists were Jewish, like Isachar Ber-Rybak, who spent much of his career in Kiev. In 1918, he helped established the Kiev Kultur-Lige, a league for the study and promotion of local Jewish culture and traditions. Also active in the group were Abram Manevych and El Lissitzky. Other artists from the exhibition would likely have identified as Russian, like Alexander Rodchenko. At times, they might have discarded with the idea of nationality altogether and instead called themselves Soviet artists. Certainly, this was the case with Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, and Kazimir Malevich. For Alexandra Exter, gender was considered to be an important factor in self-identification, as much so as any factor of nationality, religion, or citizenship.

So what do all these artists, diverse as they are, have in common? How can we justify exhibiting their work under one roof? Nearly all of them, at some point in life, lived and worked in the territory of Ukraine, either in its western Polish half or its eastern Soviet half. This is one main site of convergence. There were even some artists who chose to move there, some from Russia and others from western Poland. One thing that attracted artists to Ukraine was the high level of training available at the Kiev academy and other art schools. Another issue was the relative tolerance at these institutions for artistic experimentation and for the enrollment of Jewish students and women, through the late 1920s. By this time, the situation in Russia was already hardening, favoring explicitly political art. And this made Ukrainian cities like Kiev brief havens for modernism and artistic pluralism. Another significant factor was patronage. All of this is worth underscoring. The great traction that modernism gained in Ukraine depended heavily on its institutions: art schools, organizations, exhibition venues, and magazines, established by artists and their supporters. And not many of these individuals were concerned with fashioning a Ukrainian art as such. More often, they were simply interested in nourishing a place for art in the places where they lived and worked. I don’t see major differences today. I haven’t heard many younger artists in Ukraine speaking of a lack of Ukrainianness in art. For the most part, their main concern is for creating a viable and open arena for their work.

Myroslava M. Mudrak:hank you for that summary Nick. That was really a great way to plunge into the issues at hand. I, too, prepared some statements about what I would call the “hybridity” of Ukrainian modernism. Not only do we see aesthetic paths intersecting through Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism, we’re also reminded of Gustav Klimt, El Greco, and Otto Dix. These varied directions are associated with the entire interwar period of Western Europe; they surface as well in the Ukrainian art that we see in this exhibition. So the next question would be, what is unique about it? What is different about it? What singles it out? Why can’t we just enfold these works within the context of Western European modernism as a whole and leave it at that? I think the issue at hand is that they are fully a part of the history of European modernism; however, they also beg for separate study and analysis to better understand what it is about the geographical territory that gave inspiration to these works. What is it they take from these lands? Why is it that when someone like Kazimir Malevich, the quintessential modern painter of the early 20th century, comes to teach at the Kiev academy in 1928, he abandons abstraction and turns his full attention to figurative art? Something must have happened when he spent his time in Kiev to effect that dramatic change in his style. My point here is: despite the hybridization of modernist styles that so easily describes the overlapping of myriad influences operating in the work of these artists, the harder task is to delve into the local culture and its regional differences and distinctions from whence these artists emerge to try and figure out what is it that gives their art its particular flavor and appearance. We see names and a sampling of images, but there lies a larger task before us: to penetrate, to probe, to better understand what is happening at the core, what gave rise to this art. What I’d like to have us think about, and I think this is where the richness of these works emerges, is that there are many ways to study modernism, and one of them, deemed especially appropriate in the study of Ukrainian art, is to tap into the distinctive qualities of site.

Vsevolod Maksymovych, Kiss, 1913. 39 3/8 in. x 39 3/8 in., oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

A prime example of the need for this kind of study is presented by the enigmatic paintings of Vsevolod Maksymovych, an artist recently discovered, whose works have been shown publicly for the first time only within the last decade and until, this exhibition, only in Kiev. Maksymovych’s art was in storage in the National Museum of Ukraine and never brought out until a few years ago. We know very little about Maksymovych. His inclusion in the modernism show reinforces our awareness and realization that the study of Ukrainian modernism is still in its nascency. To come back to my point about regionalism: if Maksymovych hails from Poltava, what is it about this renowned city—the site of Peter the Great’s conquest over the Swedes and the birthplace of the Ivan Kotliarevsky, the 18th-century author and friend of Gogol’s, who first introduced the vernacular into Ukrainian literature by translating the Aeneid—that would give Maksymovych’s paintings a distinctive quality? Should it be surprising then that Maksymovych, who lived there, would echo his roots in his art? Or, is his art merely copying (as some art historians would maintain) artists like Audrey Beardsley? Certainly, we can relate Maksymovych to the Symbolists of Western Europe, but we can also ascribe to his art the classical tradition that was native to him by virtue of his being a Poltavan. Or what about the painter Vasyl Krychevsky who introduced the Style Moderne into Ukrainian art in his daring design for the Poltava Zemstvo to create a fusion of modernist clarity and simplicity with the abstract motifs of local handicraft traditions? Or Maria Syniakova, based in Kharkiv, who melded the influence of Matisse—especially his color and loose brushwork—with Orientalizing motifs inspired by Persian miniatures and Turkish kilims?

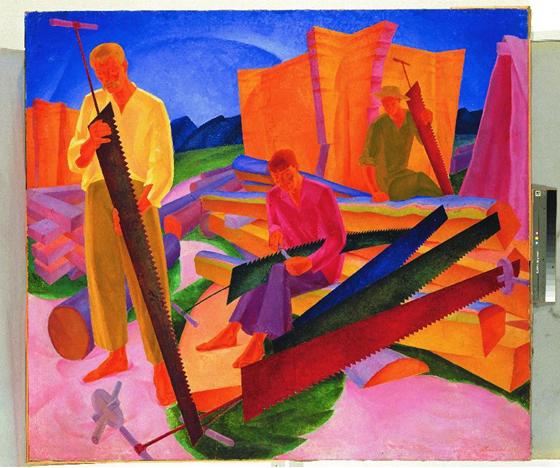

Oleksandr Bohomazov, Repairing Saws, 1927. 54 3/8 in. x 61 in., oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

Another artist that comes to mind is Oleksander Bohomazov, the painter of Men Repairing Saws, a Cubo-Futurist turned pedagogue, who taught color theory at the Kiev Art Institute. That work has been seen as rather anomalous in the Bohomazov’s entire oeuvre. Indeed, Bohomazov was a kind of free spirit; he loved Italian Futurism and he loved quaint subjects—his wife, his daughter, cats, people working in the streets. Most of his paintings are very light and breezy. Yet, suddenly, in 1927, at the time that he was a professor at the Kiev Art Institute we see this rather terse work that becomes much more concrete in its imagery as compared to his earlier period. The colors are sharp. One wonders what is happening in this particular work. This is where it is necessary to dig into the culture to better understand why this shift of consciousness and style occurs. Bohomazov was not only a very talented painter in his own right but he was an excellent pedagogue. In 1914, he wrote a manuscript on the elements of painting, an unpublished essay that broke down the conventional principles of what it is to paint and the process involved in choosing specific color, line, or shapes. Bohomazov wrote his text in the form of a pedagogical treatise. If it had been published, we would find echoes of Kandinsky’s classic text on the spiritual in art (published in 1912). Kandinsky, who as a professor to Bauhaus in 1927, publishes an expanded version of his 1912 text called “From Point to Line to Plane.” If you compare the excerpts from Kandinsky’s 1927 essay and Bohomazov’s unpublished text, you would think that it is the same author. There are illustrations in Bohomazov’s text that actually relate to illustrations and diagrams that Kandinsky used in his 1927 Bauhaus publication. So where does Bohomazov’s writing fit within the history of theoretical treatises relating to modern art? Moreover, where does he stand in relation to other painter-pedagogues of the same era? What is it about pedagogy and its relation to modern art that also asks for our attention?

What I’d like to suggest is that Bohomazov’s Men Repairing Saws is not a painting of an individual artist’s self-expression; rather, is a paradigm of painting, a pedagogic example of color theory. If we really study this work carefully, we would find parallels between Bohomazov’s painting and the color theory of Ostwald who published his work in 1916. Ostwald was very popular in Russia, and was obviously studied very closely by Bohomazov in preparation for his teaching at the Kiev Art Institute. Indeed, Bohomazov’s Men Repairing Saws demonstrates Ostwald’s system of the four principal colors and their complementaries. The “fanning” out of saws and logs in Bohomazov’s painting, is not so much a theme of workers and labor as one would be inclined to identify it in the latter part of the 1920s; rather it is a working out of a system of color appropriate to such a theme. So while Bohomazov’s famous painting might suggest to some a turning point, specifically the abandonment of the independent creative spirit that had once marked the exuberance of his Cubo-Futurist paintings, and that his emphasis on terse figuration and an overt “proletarian” theme indicates the dramatic shift in aesthetics that would evolve into Socialist Realism, in fact, what we see is that Bohomazov was introducing his students to advanced principles of color theory, in complete compliance with the modernist project of the early twentieth century. His work serves as evidence of grounding modernism in the educational system of Ukraine, and specifically of the Kiev Institute. This is an aspect of how modernism evolved in Ukraine that remains to be studied.

The curriculum at the Kiev Institute can really be seen as a parallel to that of the Bauhaus. As within the Bauhaus, architecture and mural painting were integral to its program, involving the study of materials (new and old), as well as the resurrection of ancient techniques for modern applications. The Kiev Institute produced a generation of muralists, the Boichukists, who painted frescoes, and who revived tempera painting by studying the art of the Italian Quattrocento. In this practice, led by Mykhailo Boichuk (whose work is also in the exhibition), we have a return to tradition and to traditional materials, examined and re-examined as a way to connect with Ukraine’s medieval and Byzantine past, but also to create a contemporary style for the present. Neo-Byzantinism was not regarded as backward looking; instead, it was a way to revitalize links with the processes of art.

This leads to my final comment: although we would want to seek identity in the works in this exhibition, what these works provoke is a discussion of a larger sort and one with greater implications for cultural identity. How does one deal with this art that has been marginalized by the canonic narratives of modernism? How does it expand our understanding of twentieth-century modernism? How does a territory, a culture, a people who in claiming a voice within the cacophony of modernism, establish an artistic identity, especially in a land where there was no established academic tradition in the manner of national academies in the rest of Europe? If artists in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries wanted to get professional training they had to go to the Petersburg Academy or to Moscow. In 1918, the first academy was established in Kiev and the artists that you see here, Vasyl and Fedir Krychevsky, Mykhailo Boichuk, Oleksander Bohomazov, these were the professors appointed by the first president of Ukraine, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, who founded the academy. Similar to Walter Gropius, Hrushevsky chose avant-garde artists to become the school’s first professors, so there is a similar practice being undertaken in Ukraine. This was truly a beginning, a new ground, for training modern artists in Ukraine. It wasn’t fighting stodgy tradition, but refreshing and revitalizing tradition, without the need to reject nonexistent artificial systems, because there were none in place. Instead, it developed by the sheer attachment of the artists to the land where they lived and worked.

Andrew Wachtel:I’m not an art historian, so I’m rather different than my colleagues, all of whom have the privilege of being art historians, so that means they know something and I don’t, and that’s probably good. What I want to talk about is not what individual artists in this show may have been trying to do, although I think that is an interesting topic. I’m also not going to talk about what their work looks like. What I am going to talk about is why this show looks the way it does. Who wants this show? Who needs this show as a show of Ukrainian modernism or modernism in Ukraine? It is very interesting that the catalog is titled “Ukrainian Modernism” and the brochure is called “Modernism in Ukraine”—and I’ll get to the reasons why that’s an extremely interesting paradox. So there are two ways to understand an art exhibition like this. It is a collection of artists but someone puts themtogether, some collective in most cases, and decides that we are going to take these artists and call them either Ukrainian modernists or modernists who worked in Ukraine, and that implies something about Ukrainian culture at the time these works were created. In fact, it tells us much more about a desire of people today to create an image of Ukrainian culture both now and in the modernist period.

What do I mean by this? There are two ways you can create a concept of national identity in a heterogeneous state, and all states are heterogeneous no matter how much it seems that everybody in a given country is “the same.” If you actually talk to them, they can see all kinds of differences. For example, we may think that all Swedes have blond hair and are tall, and so they are much more homogeneous than Americans. If you go to Stockholm all the Swedes will say, “Oh those people in the South, they’re not really Swedes.” So they see these differences. Any society has its differences and its similarities and it’s up to that society to focus more on the differences or more on the similarities. In a given nation, you can have two different concepts. One is what we would understand in the United States as a citizenship concept. Anyone who lives here and is willing to live according to the laws is one of us. You can be a Mexican-American, a Lithuanian-American, a Serbian-American in Chicago, and you’re all Americans even if you eat different things, celebrate different holidays, and even speak different languages. There’s no problem, you’re all Americans, ultimately. That’s generally not the view that European nationalisms take. European nationalism tends to be more restrictive; it is not good enough to say, “I’m a Pole” if you aren’t Catholic and you don’t go to church. Then from the perspective of lots of Poles, and probably from the vast majority of Poles, you are not a Pole, even if you think you are a Pole. It doesn’t matter.

This exhibition, which includes artists who quite obviously would have identified themselves as Jewish artists, as was pointed out by Nicholas, artists who are Russian to the extent that, in some cases such as Olga Rozanova, one would be hard pressed to find any connection to Ukraine. I’m sure she was once in Ukraine, but I don’t quite understand in what way she could be considered Ukrainian by any European definition, actually even by an American definition. What you see in this exhibition is clearly a very strong desire on the part of its creators to say Ukrainian culture is a big tent. It is, essentially, what we would understand as a citizenship culture. You can identify with the Russian avant-garde more than with some Ukrainian folk traditions, you can identify with Jewish traditions more than some core ethnic Ukrainian traditions, and we’ll still call you Ukrainian—we still want you in our culture. Now given the fact that inside Europe the opposite version, the ethnic version, caused the mass slaughter of huge numbers of people even into the 1990s (with the wars in Yugoslavia mostly being fought over that kind of thing where people said I’m a Bosnian, and someone said no, you’re not a Bosnian because you speak slightly differently or you’re a Catholic or a Muslim so I’m going to kill you), one could argue that this is a very important development. It’s nice to see a country like Ukraine want to embrace all of the heterogeneity that was part of its culture.

The problem is that vision, the vision implied here, is not one that everyone in Ukraine, if you look at politics and contemporary history of Ukraine, would actually agree to. As we know from most recent elections in Ukraine, there is a very strong divide in Ukraine between Russian speakers and Ukrainian speakers who sometimes think of themselves as the only Ukrainians in Ukraine. The Russian speakers might dispute that. I’m not going to get into the question of who is right. It really doesn’t matter who is right. What matters is that two different visions exist for what it means to be Ukrainian. Suppose you live in Kiev and do not want to speak Ukrainian. Are you allowed to call yourself Ukrainian? The organizers of this exhibition would implicitly say yes; that’s okay. You can be Rodchenko, who almost certainly did not speak Ukrainian, and certainly did not spend a lot of time there, but had a Ukrainian last name. You can be Rozanova who had a Russian last name, didn’t spend any significant time in Ukraine, but you count. The two titles of this exhibition point out that question. Is it Ukrainian modernism, which implies that somehow all these modernists have something in common that makes them Ukrainian modernists? Or is it modernism in Ukraine, which means that anyone who happened to be in Ukraine and was a modernist counts and is essentially part of our citizenship group? Pretty clearly the exhibition is modernism in Ukraine. It’s not Ukrainian modernism. I don’t even understand what this title “Ukrainian Modernism” could possibly mean in the context of this show, insofar as I have in mind what the people creating these works cared about. But I do understand what it means when I think about who has created this exhibition and what they want to get out of it. Whether or not the exhibition, in fact, reflects the actual political realities of Ukraine today is an open question and how you deal with the fact that certain groups, culturally inside Ukraine today might feel themselves rather marginalized and yet here play an important role, is a question that the exhibition doesn’t answer. It just kind of implies that there is no problem, when we know politically there are some serious problems. It’s a very strange tension then between what the exhibition seems to be trying to do and how it seems to be trying to do it with various concepts of what it could mean to be a Ukrainian artist at any period, but in the modernist period in particular.

Susan Snodgrass: Well there are certainly a lot of issues at play. I’ll try to address some of these, pull some things out and, again, leave an opportunity for others. I think all of the panelists are in agreement that Ukrainian modernism is diverse, hybrid, international. Or, as Andrew just suggested, it doesn’t actually exist. So it seems there is an agreement about the fact that it is difficult to define. Perhaps what is less difficult to define are ideas about cultural identity or national identity, but we might ask if national identity is something that is imposed, whether it is imposed by the oppressive forces in power during the time period that this exhibition takes place, or by a current cultural apparatus that is trying to create a new kind of identity? There were some other issues that we brought up that I’d like to delve into, one being, as I mentioned in my introduction, the importance of folk art forms in several of the artists’ work and as discussed in the catalog. How specifically were folk art forms used and why? How were these forms translated into a modern visual language?

Myroslava Mudrak: Here have been several essays on the kinds of folk art that have been incorporated into the work of someone like Alexandra Exter or Kazimir Malevich, and I think that it would be interesting to do the kind of exhibition, I think it was called The Primitives, that took place with the Russian avant-garde. There were objects of folk art then avant-garde works of art placed next to these, so you could see the borrowings. Someone like Exter really studied these motifs, particularly embroidery motifs. It was a kind of mutual borrowing: the artist borrowed these motifs from the folk arts and the folk artists were given abstract designs which they would then embroider or weave. There was a cottage industry outside of Kiev where Exter was very closely connected with the women who would make these objects. If you look at some of Exter’s Cubo-Futurist works, they seem to echo some of the designs, particularly the dividing or quartering of the canvas, or the use of an ovoid form, these silhouetted forms, color next to color. You could also look at the Pisenka, to the Easter Egg, and you could see that this is indeed an artist who has studied this particular peasant art form very carefully. She modernizes it but, nonetheless, the inspiration is there. There’s a wonderful painting by Exter in the Museum of Modern Art, which is actually a reference to the Pisenka, so we know that she has been looking at the Pisenka directly.

In the case of Malevich, this may seem a little bit stretched, but if you think along these lines then it certainly seems plausible. The white-wash surfaces of the peasant houses, the white-wash surfaces of the interior hearth, with its dark opening where you bake your bread—that is a very striking visual image. Malevich frequently spoke about the white-washed houses, that plain air, that simple surface. It is possible to think about these childhood references, but he returns to these sorts of motifs later in life as having a direct influence on his art. These are formal translations, not reiterations, that any artist who is visually astute is going to notice.

Andrew Wachtel: All the cultures of Eastern Europe that built national cultures started on the basis of folklore. That was the basis of the national revival in every single country in Eastern Europe. At first, there was a kind of slavish translation of folklore into more modern activities, and many of the modernist painters and poets in Ukraine were trying to get away from that. There’s a very interesting book titled Ukrainian Futurism by Olech Ilnisky who takes a very narrow approach to Ukrainian modernism. He really only considers those artists who stayed in Ukraine for their whole careers and does not bother much with Russian artists. He has a pretty narrow approach, which has its merits. He describes the poet Mikhail Semenko, whose portrait [by Petrytsky] is in the back, complaining about this kind of folklore use in the 19th century. He says that Semenko scoffed at this nationalist approach, condemning typical “Ukrainian choirs,” “the cult of Shevchenko,” “wrapped in embroidered ritual cloths — in short, every sort of cultural trivialization regardless of its political hue including the Red and Proletarian.” He belittled those who would build the proletarian culture on the basis of folk songs, who would sit with their bloated bellies listening to a tiresome opera in Ukrainian. It is this idea of balancing between, on the one hand, being fully international, borrowing anything from any European culture (which you don’t really want to do because then you have no national identity), and, on the other, having too narrow a national identity based on very specific folkloric motifs, which you can borrow and use but if you get stuck with them then you’re provincial and essentially no one cares. If I were to take back what I said earlier and say that I do believe there is something connecting all these artists, which I don’t, I would say that what they are trying to do is that balancing act. Most of the artists are trying to use that folkloric stuff without being condemned to being provincial artists, which is a tough balancing act.

Nicholas Sawicki: One of the things worth remembering is that all artists, when they move to a city, when they live in a particular location, look around themselves and adapt motifs, subjects, colors, and themes that come out of that environment. It’s useful to consider what value and role this adaption has in the artist’s work. Are we dealing with artists who are consciously trying to construct Ukrainian art or Ukrainian identity of their own by using these sources and references? I think there is a distinction to be made between the kind of borrowing that any artist engages in and a borrowing that has a distinct political underpinning. I would also add that we are making repeated reference tonight to the local. We are talking about cities like Kiev, Poltava, or Odessa, and stating that these cities have institutions and traditions that fuel artistic production. We are not really speaking of Ukraine as a whole.

Adrienne Kochman: Identifying local or even regional idiosyncrasies and commonalities is an important step in creating a national identification and then a meta-language for what is Ukrainian art. As I mentioned earlier, Ukraine certainly has other obstacles to overcome such as gaps and alterations in documentation. In the early twentieth century a number of Central European national art histories — in Poland, in the Netherlands, even attempts to write a Russian art history that was deemed organic and authentic — are common and begin at the local level. As an example, Russian artist and critic Igor Grabar wrote an article “Zwei Jahrhunderte Russische Kunst” or “200 Years of Russian Art” for the German art journal Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst in 1906 for Western audiences. It is an interesting study because it is actually a direct answer to another history Geschichte der Malerei that was published twelve years earlier by Richard Muther, a German art historian who wrote a multi-volume history of Western European painting from the eighteenth to the end of the nineteenth centuries. Muther’s book was immediately translated into English and became quite popular in Europe and the United States. His criteria for quality and modernity in painting were based on the notion that from each nation a unique, organic, artistic style developed, generally modeled on an evolutionary principle. Almost word-for-word, Grabar addresses Muther’s criticism’s of Russian art for its shortcomings by asserting that art in the Russian Empire developed on its own terms. He stresses local, including Ukrainian, contributions to a larger Russian artistic identity, for at that time, Ukraine was part of the Empire.

Susan Snodgrass: Now, I would like to shift the conversation away from the exhibition towards the present. We all know the importance of someone like Malevich to the history of contemporary art, but what impact did/do the artists represented in this exhibition have on contemporary Ukrainian artists? For example, in Poland, the Constructivists had a huge impact on subsequent generations of Polish artists, even during the communist years. Formally, the work looked different but there was a strong conceptual thread that connected this art to the art of the 1960s and ‘70s. What are the concerns of contemporary Ukrainian artists? I know the balancing between the global and the local is certainly one. Can you address some of these subsequent generations issues?

Myroslva Mudrak: I’d like to say that first of all this art has been around for about fifteen years, so to sense an impact or a kind of a natural outgrowth the way it was in Poland—we don’t have this because there was a rupture there. I remember in the seventies talking to contemporary artists who were able to follow in trans, trying to make links with the ‘20s and ‘30s with progressive art forms. Ivan Marchuk became very popular in contemporary times, but he really stands out as an individual who serves to link up the art of the 1920s with the art of the ’70s and ‘80s. He was trained in western Ukraine by Roman Selsky, an artist who comes out of Polish surrealism, who received a Western kind of training because it was possible for him to relay these new ideas to his students and that understanding of modernism went underground. Only now are we finding that private communication with teachers carried these Westernmovements forward, but for the most part, this art is not having that great of an impact on new artists. In an exhibition of contemporary Ukrainian art that took place in Scandinavia, the artists created a catalog, trying to fit themselves into this trajectory, but it was not a clean fit. I think they are really trying to establish a different orientation for themselves and not link up with the avant-garde artists in this exhibition.

Nicholas Sawicki: I would say that for most living artists in Ukraine today, the body of work in this exhibition is not an immediate reference point. Few living artists in Ukraine remember the 1920s, and they are often still grappling with the legacy of late socialist realism. In some sense, it may be digging too far back to suggest that there is some lasting imprint, sort of like expecting that an artist working in the United States today should go back to looking at a painter of the 1920s, like Grant Wood.

<p>Susan Snodgrass: I guess the question should be rephrased. If it’s not necessarily the direct impact of these artists, then were there certain avant-garde traditions, whether they are the ones set forth in the work we see here, or another kind of avant-gardism that has carried through?

Adrienne Kochman: Here are parallels between the early twentieth-century Ukrainian avant-garde with contemporary Ukrainian artists’ interested in Western artistic development. Yulia Vaganova, co-curator of last year’s “Artists Respond: Ukrainian Art and the Orange Revolution” exhibition at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art mentioned younger artists who were very interested in new technologies. Many of them were working in film, video, and nontraditional, nonacademic media. A number of them found that they had to go into Western Europe, England, and the United States to do this kind of work. At that time they couldn’t get the attention of the Ministry of Culture to gain any kind of governmental support for their work. There is a divide in Ukraine between art that is considered to be contemporary, art that is “out there” and experimental, and art that is modern. New emerging artists are trying to go outside of the traditional exhibition format, and it is tied into politics. To them, the emphasis by the government on conventional art (painting, sculpture) is just as restrictive as the Soviet system was to their freedom. They want exposure to the West because it gives them more opportunity and validity for experimentation. It appears that a number of younger artists aren’t necessarily aware of this [Ukrainian modernist] art and its relationship to the West in the same way we are. They do not have a connection to that kind of history.

Andrew Wachtel: In general, the issue with art and literature and all cultural production in Eastern Europe is complicated because these people have gone from being perceived as the underground who carried the voice of true values and democracy, which is what their role was in the late dissident era, to being completely marginalized. Ukraine is actually in better shape because of the political turmoil. In most of Eastern Europe where now you have European-style governments, artists have nothing to do at all and no one cares about them because in the public sphere they do not need artists the way they used to. Governments have not gotten rich enough to subsidize artists doing the crazy things that Western European governments are willing to subsidize. Part of the reason artists wanted to go to England was because in England you can get a subsidy to stand on your head and do some strange artistic happening, whereas in Poland, the government will not give you one. So the question is what is the role of art in this society now that hasn’t shaken out yet.

Susan Snodgrass: Before I turn our discussion over to the audience, I want to make a couple comments on what you said about mechanisms of support. You talk about governmental support for contemporary art. I know that the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, which is or was active in Kiev and throughout Central and Eastern Europe post-1989, gave the first and sometimes only form of private support for contemporary art. A lot of the work that was supported and produced, or at least the work that I have seen in international exhibitions, is video and other forms of new media. Contentwise, much of this work deconstructs historical images, such as socialist propaganda films, archival material, or photographs from the Second World War. There seems to be an interest in the media and various deconstructivist strategies.

We have had a flavor of the contemporary, and we have talked a lot about the exhibition and the various issues both contained within the works and surrounding their interpretation. Now, I want to turn our discussion over to the audience.

Audience Q: Does Marc Chagall fit into any of this history? If so, where?

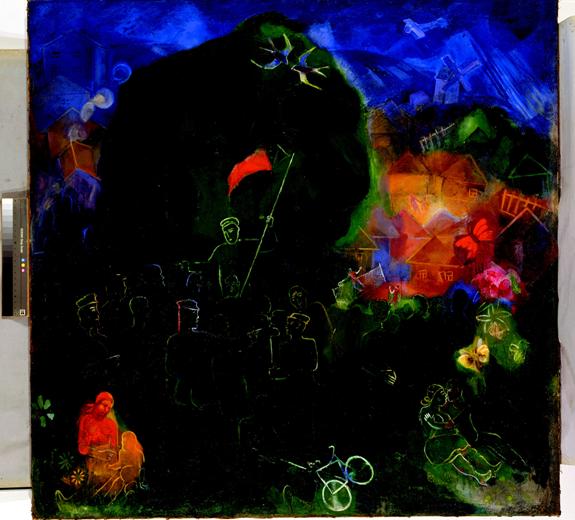

Victor Palmov, May 1st, 1929. 63 3/8 in. x 63 x 3/8 in., oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv.

Myroslava Mudrak: Marc Chagall worked in Vitebsk, which today is Belarus, and then he went to Paris. There is very little connection, but it is worth examining. The work of the colorist Viktor Palmov that we see here, in both subject and the treatment and transparency of color, I think there is a certain kinship that we can find between Palmov and Chagall, and this is a kind of art historical mini-story that is worth looking into. At this time, there is no point of reference or time to speak about it.

Audience Q: What impact did the oppressiveness of Russia have on this work?

Andrew Wachtel: It had a very direct impact on those artists who were killed in concentration camps and accused of Ukrainian nationalism so in that sense for some people it had a pretty negative affect. For other artists in this show, many were dead long before the Soviets ever got there. Others, like Rodchenko, were perfectly happy inside a Soviet context. Again, let me tell you the extent to which there is no Ukrainian modernism. The Russians were not particularly those who considered themselves Ukrainian, and they suffered. Just because you were in Ukraine did not mean that you were necessarily Ukrainian. You might be safe, but it varied enormously for the different artists in this show. Generally, the Soviets were not too happy with what we call modernist art. That is why nobody saw this work between 1932 and 1970. It was there, but stuffed away. The Russians suppressed Russians just as much as they suppressed Ukrainians. They just did not like modernist art, period.

Nicholas Sawicki: This exhibition ends at 1930 without a real hint of what happens later, and it doesn’t address what happens to these artists in the era of Stalinism. Criticism was cast at the Guggenheim’s recent exhibition Russia! for similar reasons, since it glossed over the same issue. In 1937, Boichuk and his wife were shot and killed by the police, and certainly there were great constraints imposed on artists in the 1930s. It would have been interesting if the exhibition had included information like this to situate us historically.