Transit Visas Are Not Being Issued Here: The Loop as Symbolic Form On Clemens von Wedemeyers Short Film “Otjezd”

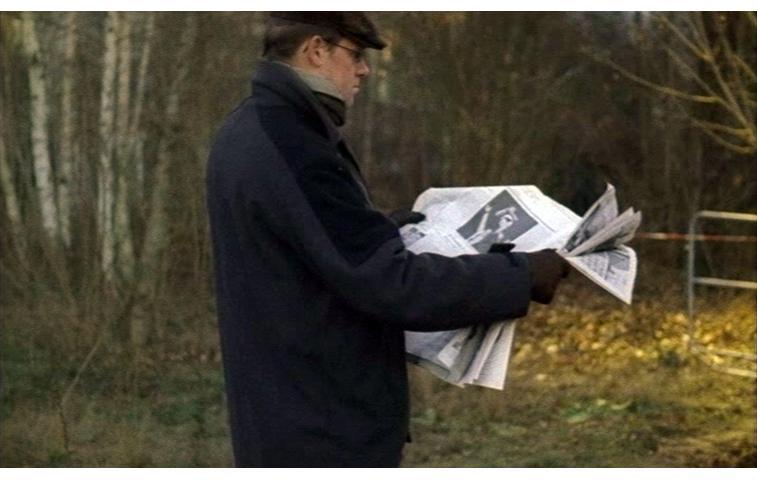

At first glance—for those who grew up with Eastern European cinema—Clemens von Wedemeyer’s film “Otjezd” seems so astonishingly familiar that one can not believe it was not made by a “native viewer.” Gloomy, self-absorbed characters with fur hats, stuttering nervously or reciting poetry in dream-like surroundings seem to be a reference to Andrei Tarkovsky’s famous Mirror (1975). It is only when a living advertisement dressed as a green frog appears for a split second, chatting nonchalantly with bored policemen, that one begins to suspect that something has changed. There is obviously some capitalism around.

The simple Russian word otjezd, which means departure, carries imminent historical implications of a farewell parting. In the 1970s, it was widely used as a euphemism for emigration. This is the point of no return in the Soviet Union where, unlike other countries of Eastern Europe, the Iron Curtain was particularly dense. Von Wedemeyer’s film, which stages the kafkaesque struggle with the bureaucracy around a German consulate somewhere in contemporary Russia (although in an unlikely, surrealist setting), still connotes a one-way journey. An authoritative voice announces, with irritation, that “transit visas are not being issued here.”

Standing in a line—a grim symbol of socialism–can also be seen as a symbol of linear movement, progress, and a spatial expression of history. In the Soviet Union of the 1970s—an isolated territory where time stood still and where the future was declared a reality—all of these things were seen as essentially “Western.” To emigrate to the West was equivalent to abandoning the future for the present. By exiting from the utopian enclave beyond temporality, market-instigated differences and death that was the Soviet Union during the period of stagnation one joined the (Western) realm of linear time and the logic of cause and effect. Even when one was slowly moving forward in a queue, one was already partly on Western territory: a line inevitably formed for the opportunity to get Western consumer goods and, ultimately, for the right to live in the West itself.

But the line in von Wedemeyer’s film goes nowhere, as there is no clear border-crossing and no tragedies of irreversibility in contemporary emigration any more. Over and over—the film is shown as a loop—the female protagonist is not allowed to enter the grounds of the consulate. She then leaves but she nevertheless finds herself still there, or, to be more precise, she remains in some intermediary zone where she looks desperately for a place to put her bag. In this rare example of a consciously constructed visual loop, the linear logic of history is challenged, even destroyed, in favor of the circular logic of repetition.

The film was made in one single shot, a technique that has tempted other Soviet filmmakers of the post-montage era (Vladimir Nilsen’s particularly long shot in Grigori Alexandrov’s “Vesyolyje rebiata” became famous), although they never achieved the total smoothness to which they aspired. In von Wedemeyer’s film there are no cuts (the one that was necessary to create the loop is hidden), which accentuates the coherence of the space. However, the sense of space in this film is confusing as it is only after several hallucinating “rounds” of the story that one begins to see that this space is in fact very small. The film was shot with a fixed camera turning around itself in an even motion.

“Otjezd” implicitly refers to the circular film panorama, a phenomenon created in the West that acquired an important socio-cultural role in the Soviet Union.A version of this text is being published in the catalogue “Clemens von Wedemeyer” (Kölnischer Kunstverein und Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Köln 2006). The circular film panorama—a technology invented in America—was developed in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s. Special films were made for this medium and many such circloramas were built in the Soviet republics and in the countries of the Eastern bloc. The West soon abandoned this kind of visual entertainment since its paying customers were annoyed by the fact that they could only see half of the spectacle and missed what was going on behind their backs. In the Soviet Union, where tickets to the very popular Circlorama at the VDNKh (Exhibition of Economic Achievements of the USSR) cost next to nothing, money was not an issue. However, the circular form of the panorama was not supposed to create any discomfort or frustration in viewer since, culturally and politically, the latter was considered a multiple body with a collective vision and a collective desire.

A circular panorama is necessarily inclusive and unfocused. Or, one could say, it focuses on “everything” rather than dividing the space into “here” and “there.” The panorama to which von Wedemeyer refers through his allusions to Soviet film is the ultimate communist art work, a utopian space felt as a potential opening in all directions, dialectically bringing together the static dimension of brotherhood and the dynamic dimension of social ascent. The panorama, unlike film, is experienced from the inside, in a corporeal rather than in a purely visual way. Other examples of Soviet architectural ensembles designed to host the proletarian masses by transcending visual art include El Lissitzky’s famous exhibition designs that overwhelmed the visitor with a new perception of space; Ilya Kabakov’s total installations, and the outdoor spatial experiments by the group Collective Actions.

The waning of time and the sense of coherent space in von Wedemeyer’s film are not just about the isolationist utopia of the communist world, they are also about the end of temporality proclaimed by postmodernism, about the alleged end of history and linear logic. There are many things that the utopia of the global market inherited from the Communist non-market utopia, such as the claims of limitless space and unconditional freedom; the pretense to be the sole possessor of the keys to happiness, and the wish to abolish death.

It seems as if the main character in von Wedemeyer’s film cannot reach the West because there simply is no West anymore. The former West, much like the former East, disappeared in the final salvoes of the Cold War. Their mutual defeat produced the global world Clemens von Wedemeyer is discovering, slowly turning around.