Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011

Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011, MoMA PS1, November 3, 2019–March 3, 2020

Coinciding with the turn of a new decade, the trove of artistic responses to the West’s lengthy military presence in Iraq currently amassed at PS1’s warehouse-sized venue focuses a new lens on recent history. Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011 is overwhelming in scale yet rich in material, brimming with perspectives that peel back the layers of this protracted, two-part conflict from the not-so-distant past, which now threatens to resurface. Many of the voices represented in the exhibition hail from places other than Iraq: France, the United States, and Britain, and also include a number of Palestinians in exile. While the exhibition sometimes stretches beyond the geographic and chronological parameters stated in the title, detracting from its premise, the all-encompassing narrative echoes the general public’s amorphous understanding of the region’s perennial “instability” and the American economic interests that underlie it.

Curators Peter Eleey and Ruba Katrib intricately weave together a narrative in which the careers and ideological agendas of Presidents Bush senior and junior become inseparable; the works’ arrangement reiterate an endless cycle of repetition wherein one Gulf War bleeds into the next. With the assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani only three days into 2020, the story that seems to play on loop throughout the museum’s meandering halls has collapsed the past into the present. The show now reads as a prelude to yet another endless Middle East conflict, or perhaps even a roadmap to navigating this all-too-familiar territory. Less than a week after Soleimani’s death, PS1’s governance became its own political lightning rod. Some of the most prominent figures on the show’s roster of artists—thirty-seven in total—put forth an open letter protesting the exhibition’s ties to two MoMA trustees invested in for-profit prisons (Larry Fink) and defense contracts with a problematic track record in Iraq (Leon Black). Now teetering at the intersection between its status as cautionary tale and target of the artworld’s crisis-of-conscience over institutional funding, PS1’s Theater of Operations has become an outlet for artists who have come to rely on their public voice as one of the few political bargaining chips at their disposal. If anything, these recent events have only contributed additional political weight to the works on view.

PS1—an abandoned schoolhouse—is the ideal venue for a show of this breadth and subject matter, particularly in the hints of decay ingrained in its walls. Unexpected and semi-hidden displays appear pocketed away in areas such as the boiler room that sits across from the coat check. In this dark, dank space, save for a small, square hole emitting natural light, visitors can catch a screening of the short documentary National Works (2012/2019) by Jordanian artist Ala Younis. The film captures the contents of an eponymously named museum in Kuwait (closed in 2017) comprised of cardboard dioramas that recreated specific Gulf War battles, all presented from a local perspective. To see this particular video in such a low-ceilinged, starkly lit room filled with the smell of gas and the cold of winter feels like reliving someone else’s traumatic memories in an underground bunker. Flashes of light on the screen intermittently call attention to the obviously artificial and constructed quality of these humanmade models and staged battles, the blatant falseness of which helps to visualize the type of out-of-body experiences common to victims of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD.

Installation view of Thomas Hirschhorn, Necklace CNN (2002). Courtesy MOMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

On the ground floor, Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn’s comically large, foil-wrapped gold chain titled Necklace CNN (2002) formally opens the show, setting the stage for one of the exhibition’s overarching themes: the observation that the media underwent a paradigm shift with its coverage of the Persian Gulf War, the first of its kind that could be followed “live” in real time. In the aggregate, Theater of Operations is as much about the media experience of watching the Gulf Wars unfold as it is about the combat itself. It shines a light on what was said, as well as what has been left unsaid, pointing shrewdly and relevantly to the breakdown in trust over media institutions that began to accelerate in the 90s, embodied here in Hirschhorn’s ironic, mocking eight-foot-long “necklace” dangling on one of PS1’s painted brick walls.

Installation view of Michel Auder, Gulf War TV War (1991, edited 2017). Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Moving chronologically from 1991, the first floor exists as an uncanny time capsule immortalizing the early Gulf conflict and the media’s framing of it as a new imperialist project that the US embarked upon following the Cold War. French artist Michel Auder’s Gulf War TV (1991) is a record of the artist’s own television-watching experience in his New York City apartment as Operation Desert Storm unfolded. Punctuated by constant changes in programming and frequent commercial interruptions, Auder recorded the contents of his television screen in real time, capturing the media’s relentless efforts to capitalize on the attention economy in the days when cable television reigned supreme. The dopamine-inducing channel surfing gives Pop-Tart advertisements, Woody Woodpecker cartoons, and Bob Ross’s daubed collection of “happy trees” the same moral weight as news reports on war casualties. Although the news is emphasized here, the film’s content does not remain exclusively focused on the conflicts in the Middle East, but shifts to peripheral, yet related subject matter, such as blips in the stock market and changes in oil prices. What Auder so astutely captured in this work were the early stirrings of infotainment that has since come to dominate cable news television with his use of dramatic fonts and graphics to frame news stories and cinematic titles such as “Showdown in the Gulf” and “America at War.” At several points throughout the film, he superimposes the words “Fake News” over his recordings. In this simple yet effective manipulation of his mundane TV-watching experience, the artist forwards his own oddly prescient commentary on the deceptive tools of mainstream news.

It is here on the first floor that the exhibition anchors its textured critique of the war as a heavily manipulated fiction, brilliantly deploying the “theater” referenced in the show’s title. American artist Karen Finley’s wall-sized diatribe The War at Home, first conceived in 1991 and repainted at PS1 for this exhibition, portrays the first Gulf War as the logical conclusion of a culture steeped in hyper-masculinity. In hand-painted cursive, the artist rails against the excesses of a country that ignored the AIDS crisis while involving itself in another foreign conflict, comparing the macho chest-beating of the US war machine to an NFL game. Finley’s text pairs well with American Mary Kelly’s Gloria patri (1992), a series of polished aluminum shields, medallions and trophies that both sarcastically glorify and openly undermine the ideal of the manly warrior and the exaggerated gender politics that it implies. Most importantly, both of these works emphasize television’s role in the myth-making process in its curation of only select snippets of information, making it all-the-more-difficult to piece together the truth. The occasional backstage view of the war operations that the exhibition provides through the artists’ critiques, revolves around the sanitized farce that the war was a bloodless, tactical precision game perfected by warfare technology; obviously not the truth of the matter.

Nuha Al-Radi. Portrait of Zain Habboo. 1995. Painted metal canister and rock, 10 × 6″ (25.4 × 15.2 cm). Collection Aysar Akrawi. Courtesy MOMA PS1. Photo: Kris Graves

Neo-traditionalist works of art, such as Baghdad-born Nuha al-Radi’s renditions of Sumerian and Neolithic votive figures from the early 2000s as well as fellow Iraqi Hiwa K’s Bell Project (2007–15), memorialize the region’s rich, textured history, and help to emphasize the cultural cost of ongoing conflict. For Bell Project, Hiwa K melted together various metal battlefield detritus, such as scraps from bullets, bombshells, and mines. From this recycled material he molded a European-style church bell adorned with reliefs of Akkadian Lamassu and replicas of the bronze mask of Sargon of Akkad that was tragically looted following the American invasion in 2003.

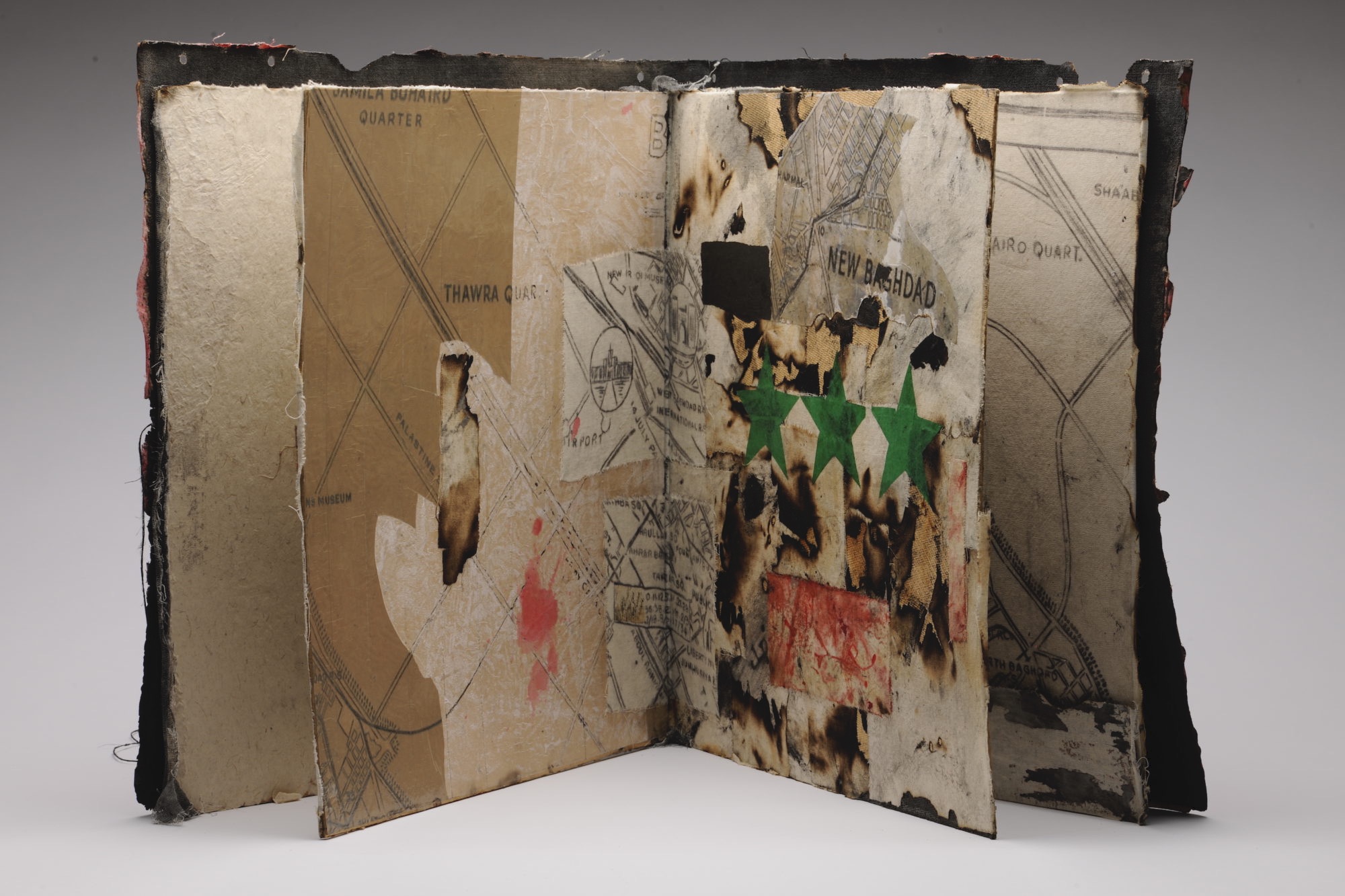

Hanaa Malallah. Baghdad City: US Map. 2007. Mixed media (ink, collage, burning, and tape on wood) 20 7/8 × 21 5/8″ (53 × 55 cm). Courtesy MOMA PS1, the artist and Azzawi Collection, London. Photo: Anthony Dawton.

The quality of the art on display can at times appear uneven, which can actually work to the advantage of the exhibition’s larger narrative arc by helping to document the ways that foreign intervention has culturally and economically impoverished the region. It spotlights the material conditions of those artists living and working in Baghdad and other combat zones at this time, who due to sanctions did not have access to fine art supplies other than portable paper books referred to as dafatir. In some cases, scarcity also lead to artistic innovation. For example, in her large-scale work Ruins Roar (2015), Iraqi-British artist Hanaa Malallah’s took the art of “ruins” to another level by collaging layers of burnt canvas onto a support, a destruction-based technique that she developed in the 1990s out of necessity, using the only scraps that she could find. Iraqi director Oday Rasheed’s docufiction film Underexposure(2005) more fully realizes the occupation experience, images of which are embedded in the harrowing story of the film’s production. The cast and crew even sold their possessions to help pool money to fund the picture. Captured on expired Kodak filmstock, the only kind available as a result of US sanctions, the tawny tone of the celluloid matches the tenor of the film itself. Both the medium and the filmed subjects appear aged before their time

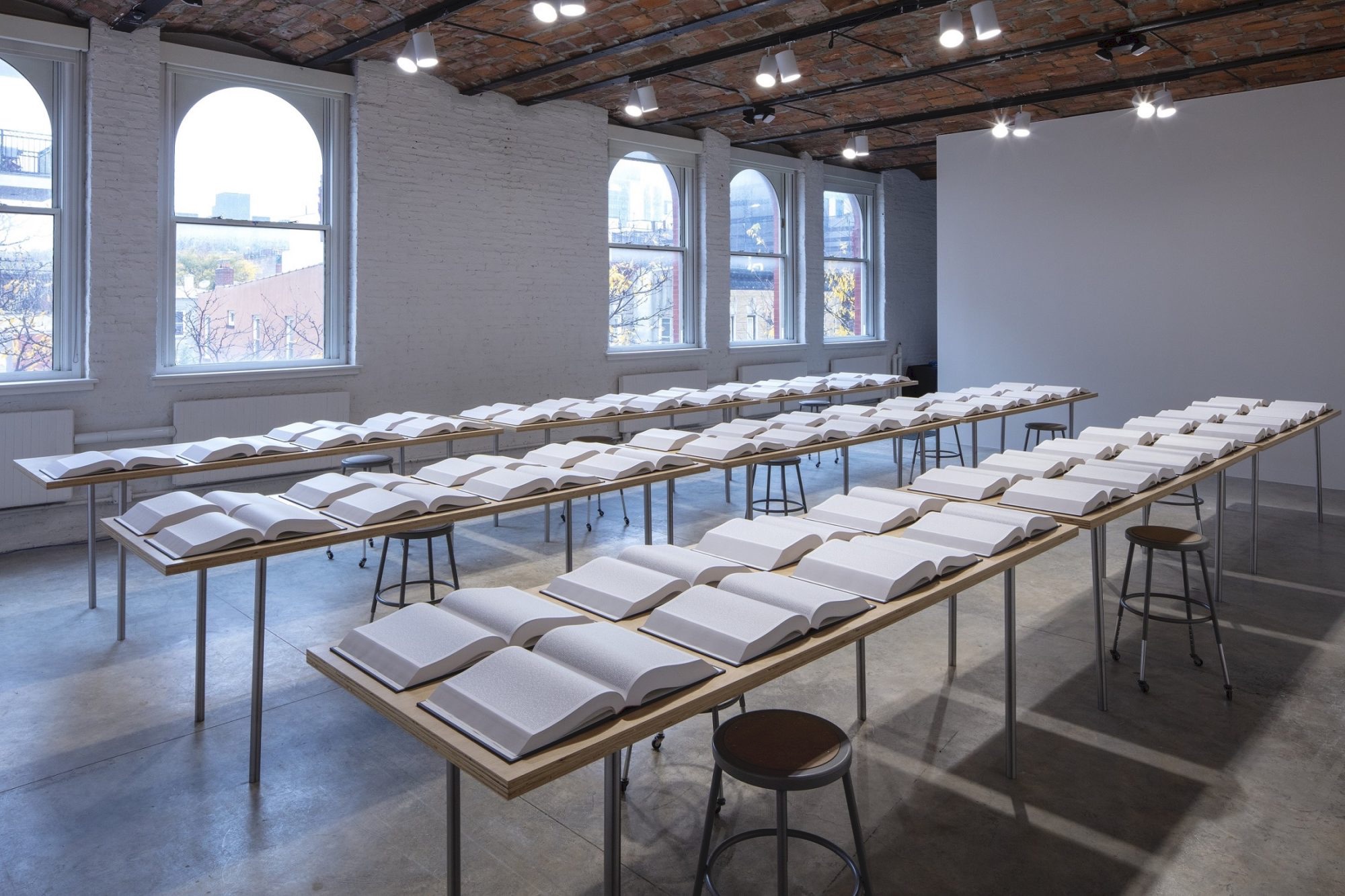

Installation view of Rachel Khedoori, Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2008–2010). Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo by Matthew Septimus.

Nothing if not comprehensive and exhaustive—even sometimes exhausting—the exhibition meanders from the easily accessible, such as soldier portraits by American Judith Joy Ross to the work of Rachel Khedoori, an Australian artist of Iraqi-Jewish decent, whose more conceptual work Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2009–10), consists of a room with seventy typewritten tomes laying open on a table in illegible nine-point font, visualizing the overwhelming breadth of news information on the war. At times the exhibition’s all-inclusive approach threatens to dilute its more pithy and effective thematic threads. Many Iraq-based artists tend to be encircled by better-funded and branded names from the West who speak of the war from outsider perspectives. Some of these selections can be a bit too on-the-nose, such as Richard Serra’s Abu Ghraib linoleum-cut from 2004 based on the famous leaked photograph of a hooded prisoner and inscribed with the words “Stop Bush.” Such inclusions to the exhibition seem at times to be reaching for anything and everything that could possibly fit into the them

Appropriately, the third floor concludes with a thematic arrangement dedicated to the aftermath of the Gulf Wars – dealing with the half-life of wartime images as well as their political and emotional legacy. Two works in particular bring home the experience of PTSD visually and in the form of documentation. American artist John Kessler’s Shock and Awe (2005) places a closed-circuit TV camera directed through a cutaway foamcore “wall” aiming at the industrial bustle of PS1’s surrounding Queens neighborhood. An overlay featuring a plume of billowing fire and smoke fits just over the outline of the BP Station located directly outside of PS1, seamlessly affixing the ominous fire-red sky onto the Long Island City skyline. Kessler’s ingenious trick confounds space and time: New York becomes displaced within the haunting memory of Iraq. German filmmaker Harun Farocki deals with the trauma more explicitly in Serious Games III: Immersion (2009) in which he presents a split screen of Iraq veterans playing virtual reality digital simulations of the war while speaking to a therapist on one side; the digital reenactments appear on the other. In one such therapy session, the video component turns off once the patient begins to detail a more graphic and disturbing experience. Only then does it become clear that he is holding a rifle in his hands as he recounts his trauma.

The Irish-Iraqi artist Jananne Al Ani’s video installation Shadow Sites II (2011) is a perfect way to end the somewhat taxing experience of wading through the entire exhibition – which itself can be a traumatic, particularly for those brave enough to step inside some of the more graphic of Hirschhorn’s installations, including Touching Reality (2012), a visual archive of mutilated war-dead. Tucked away in the same gallery with Farocki’s work, Al Ani’s film presents a somewhat abstracted montage of aerial footage capturing what are called “shadow sites” of ancient and more recent architectural remains. The skeletal foundations that remain combined with the desert-like topography and the slow-moving, mechanically steady pan of satellite footage makes these locations look alien, as if they could be located on a faraway planet. Gutteral vibrations that accompany the film (reminiscent of a drone pipe) contribute to this sensation of otherness. This work speaks to the alienated position to which “the West” has come to see this part of the world — as familiar as a moonscape with its cratered, barren earth —underscoring the difficulty of recognizing this space as earthly let alone the cradle of Western civilization embedded in the archaeological ruins.

Capitalizing on MoMA’s Long Island City annex to the fullest, Theater of Operations spotlights a persistently difficult topic that has been relegated to the backburner of the public’s consciousness after nearly thirty sustained years, and which has come hurtling back into the forefront of the American media conversation as the US has involved itself another skirmish in the Middle East. The show’s sometimes-nebulous thematic reach is a reminder that Iraq is not an isolated geo-political quagmire whose political fall out has been relegated to the years between 1991 and 2011. Rather, its history underlies the US government’s restrained response to the Arab spring and the civil wars that have since followed in Syria and Yemen. Prior to the events of January 3rd, the idea of coaxing repressed memories of Iraq into the daylight had become a big ask, particularly at a time when the American public’s attention span has been so fixated on domestic policy. In spite of the venue’s connection to MoMA’s trustees and their deeply problematic investments, the PS1 exhibition valiantly approaches the task of reopening the US saga in the Middle East, illuminating viewers to ongoing repercussions of the Gulf Wars just as a new chapter of instability potentially awaits.