The “Old New” Connection Between Czech and Slovak Art

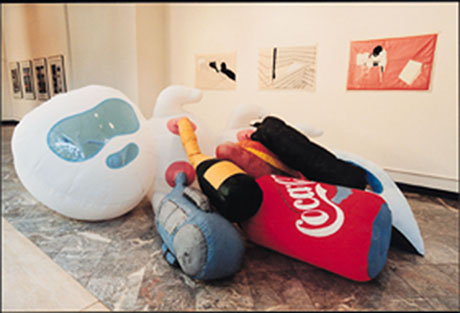

The New Connection, curated by Lubomira Slusna. Opened February 1, 2001 at the World Financial Center, New York City. Includes works by Jiri Cernicki, Anton Cierny, Michal Gabriel, Vanesa Hardi, Robo Kocan, Vladimir Kokolia, Patrik Kovacovski, Marek Kvetan, Martin Mainer, Ilona Nemeth, Michal Nesazal, Petr Nikl, Petr Ondrusek, Jiri Prihoda, Lukas Rittstein, Dorota Sadovski, Frantisek Skala, Emoeke Vargova, Katerina Vincourova, Dusan Zahoranski.

It has been more than seven years since Czechoslovakia split into two independent countries, and no matter how many international links the artists in both countries have established since, their once common connections and mutual interests have become so loose that one can barely believe that the two cultures still have anything in common at all. Yet several projects recently brought Czech and Slovak artists together again. Even though the artists might have been motivated by primarily political interests, these projects provided them with the opportunity to potentially revitalize what has been so easily dismissed and ignored.

It has been more than seven years since Czechoslovakia split into two independent countries, and no matter how many international links the artists in both countries have established since, their once common connections and mutual interests have become so loose that one can barely believe that the two cultures still have anything in common at all. Yet several projects recently brought Czech and Slovak artists together again. Even though the artists might have been motivated by primarily political interests, these projects provided them with the opportunity to potentially revitalize what has been so easily dismissed and ignored.

One of these projects was the decision to reunite the Czechoslovak pavilion for the Venice Biennial projects, after it had been divided by a wall for the past eight years. The wall will be removed for this year’s Biennial, and, unprecedented, the pavilion will be occupied by the collaborative Czecho-Slovak project of Jiri Suruvka and Ilona Nemeth, curated by the Slovak Katarina Rusnakova (inversely, the 2003 Biennial curator will be Czech).

Besides a summer “reunion” in the Venetian Giardini Garden, another exhibition opened in New York City on February 1, 2001, with artists from the country whose citizens made the Velvet Revolution happen in 1989, only to be separated soon afterwards. Curated by Lubomira Slusna, and featuring the work of ten Czech and ten Slovak artists, the exhibition entitled The New Connection became part of a month-long festival Celebrate Slovakia: Art from the Heart of Europe, and was held at the World Financial Center.

Within the last decade, all twenty artists represented in this exhibition have been recognized by a prestigious award that is given out exclusively to young artists under thirty-five years, namely the Chalupecki Award in the Czech Republic, and the TONAL Award in Slovakia. Thus The New Connection had the potential to become an important survey of the most recent trends in both countries. However, due to both the diversity of approaches that participating artists took and the various biases that invariably accompany any committee’s selection of the „best”, the exhibition also ran a certain risk. Although an in-depth survey of the young Czech and Slovak art scene would have to go far beyond any official award system, most of the artists in The New Connection belong, in my opinion, among the most remarkable in the region. Still, despite of a number of strong works in the exhibition, overall it turned out to be nothing more than a gathering of a few dozens art works that were selected without any conceptual or interpretative intent.

What does it mean to be a young artist in Central Eastern Europe of the 1990s? How do the Czech and Slovak artists communicate with each other and with the world? How do they deal with recent political and social changes? Is there any local specificity in terms of material, media, technique, themes or styles among Czech and Slovak artists in this age of globalization? If not, if their art is as „international” as art everywhere else, why is it that they remain rather invisible outside of their home region? When you try to run an exhibition of artists from the former Eastern Block in a place like New York, questions of this kind arise all the time, and, needless to say, getting the right attention (which means also an appropriate site for the display of one’s art work) is harder here than anywhere else. Still, with all the financial support and public relations that The New Connection has received, I believe that a more challenging and eye-catching exhibition could have been done with the same artists. However, I also believe that if this was a missed chance to introduce another artistic paradigm to the rather self-centered art scene of the United States, it helped at least in one respect: it made artists from two small neighboring countries pay attention to each other again, after a relatively long time of disregard on both sides.

In 1994, a year after the break-down of Czechoslovakia, I co-curated an outdoor exhibition of Czech and Slovak artists that took place in the unique Baroque gardens of the Valdstein Palace in Prague. Although my initial reason for organizing such a project was not nostalgia for the lost country, but an attempt to survey the post-1989 Czech and Slovak art, several artists in the exhibition called their new identity into question in a quite straightforward manner. In 2001, there is no indication of feelings of nostalgia, or any hints to a lost Czechoslovak identity among the artists on either side. However, there is a ground of shared cultural, political, and social experiences that still ties the two sides together, and there is also the rationale that two can do more than one, that Czech and Slovak artists together can attract more attention from the world than apart (any kind of artistic or cultural separatism that is related to national “specificities” might, after all, turn against their advocates). Of course, it would be naive to expect that the New York art scene would be flabbergasted by the show of artists from a place that barely exists on their map. Getting the international public interested in art from Eastern Europe undoubtedly takes a lot of effort, energy, money, patience, and, most importantly, a strong concept. No matter how locally prestigious the Chalupecki and TONAL Awards that linked the twenty artists of The New Connection are, these alone could unfortunately not guarantee such strength of advertisement.