The Public and the Private Body in Contemporary Romanian Art

Never has the obsession with the body been more alive than in the contemporary period, with its tendency to turn narcissistically inwards. In psychoanalysis, the term “narcissism” describes the behavior of people who treat their own bodies as a “sexual object.”Rosolato, G., “Recension du corps, in Pontalis ”, J.-B., “Lieux du corps”, Nouvelle revue de psychanalyse, no. 3 printemps 1971, Gallimard, Paris. According to observations from the same field of research, “the narcissistic behavior of identification” acknowledges both “awareness of the body” and “awareness of the self” as distinct symbolic forms, which are nevertheless in permanent correlation.

Unfettered as a consequence of psychoanalysis, freed from prejudice and taboos, the body became an expression of the self, the embodiment of its quests and aspirations. A discourse developed around the body’s endless exposure, reinforced by a true “hysteria” of the gaze, a yearning for seeing. Starting from the “forbidden gaze” Freud defined as a form of perversion, the voyeur is the one who watches an object through the “keyhole,” gazing at a forbidden detail of the object. It is usually the naked body that arouses the voyeur’s interest; but this taboo has lost the force it once had and is now de-sacralized through the proliferation of commercial sexual images. The freeing of the gaze has also been encouraged by the media which have frantically made use of the crudest everyday occurrences and images.

The contemporary artist’s interest in the body – his/her own body as “material” or as “surface” – should be examined in the context of a shift from the artistic product–an artifact about to be objectified–to the subject itself, which becomes art by exposing its own self and by presenting its own creation as a work in progress. The body is the space where a unique subjective essence finds its expression, the center of physical, sensorial and spiritual energy, as Yves Klein put it. The body may be considered an essential vector of expression, a privileged space for the artist that becomes a “visual territory” (Carolee Schneeman). This territory shapes a “symbolic geography” that still retains its mysterious regions, regions that have not been sufficiently explored and that are revealed only gradually, thanks to the objectification made possible by the artist.

A possible source for the appearance of body art would be the artist’s gesture during the execution of abstract expressionist paintings; a role-model in this direction has been the American painter Jackson Pollock who, by using the technique of gesture painting on a horizontal surface, started to paint by making movements that involved the entire body. His gesture tends to become more important than his work as such. Harald RosenbergH. Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters” Art News, (1952), in V. Export, “Persona, Proto-Performance, Politics: A Preface” Performance Issue: Happening, Body, Spectacles, Virtual Reality. Discourse, Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, 14.2 (Spring, 1992), 26. states that such gestures of painting have set American artists free from political, aesthetic and moral values, turning the surface of the canvas into a sort of “arena where one performs.”T. Warr and A. Johnes, The Artist’s Body (Phaidon, 2003), 50. The direct relation between the artist and the material surface of his work, seen as a receptacle of the artist’s gesture, highlights the degree of the subject’s involvement, whose body seems to be a sort of “tool.”

Since painting started to be considered an “arena” where the artist performed live—in public even—ritual, theatrical and staging aspects grew in importance, causing a shift of emphasis from the work (object) towards the artist (subject). At the same time, gesture painting introduced new materials and techniques, which corresponded to a new visual expressivity.

In the Vienna of the ‘60s, a group of painters affected by “the crisis of painting” (caused by the changing of the usual painting methods, as well as of traditional materials), became interested in Pollock’s and Klein’s experiments. The four Viennese Actionists – Otto Mühl, Günter Bruss, Hermann Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler – were all in search of a way of renewing the language of contemporary art and used the bodies of models or their own bodies as painting surfaces on which their released all the tension in their gestures.

These actions were no longer aimed at painting, but at the body itself, foregrounded, turned into a visible measure for human existence. In the ‘70s, the body was the means of expressing an identity established by genres. In opposition to the group of the Viennese Actionists, Valie Export openly and daringly affirmed her female identity established by her own body. In a self-portrait in which she parodied an ad for a cigarette company that had the same name as herself – EXPORT – the artist revealed herself as freed from taboos, and thus shattered the stereotypical image of the woman constrained by society. To her, the body becomes the human “measure” for the environment, for the urban landscape or for nature. It is through her body that she perceives the environment; she exposes it publicly in order to express her will to define herself and to find her own place in the ensemble. In the series entitled “Körperkonfigurationen,” Valie Export started using technology – photography and film – for conceptual art experiments, in which the body no longer appears in direct performances in front of an audience, but mediated by the filmed image. The artist uses two video cameras, one located on the back of the body, and the other pointed to her visual range, to the front, in order to test her perception.

Marina Abramović chose to use her body as “material” in a couple, together with the German artist Ulay. Both of them tested their limits of physical and mental endurance in the 1977 action called “Imponderabilia,” when, on the occasion of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Bologna, they stood naked in the main entrance, forcing the public to pass through the small space between them; the performance was filmed and projected in the halls of the museum, the two artists remaining in the same position until all the visitors went inside. They also tried to demonstrate physical inseparability in a performance during which they plaited their hair together in one plait.

The Social Body and the Political Body under Communism

Another theme that is constantly explored in the last period of Marina Abramović’s creation is identity or the relation between female identity and national identity. In an attempt to evoke her mother’s partisan past, she marked her naked body with the communist coat of arms, cut directly into the skin with a razor, in an impressive performance, fraught with pain (“The Lips of Thomas”), during which the artist sacrificed herself in the name of an idea and of a memory.M. Abramovic, Museum Villa Stuck (München: 1996), 46. The long-standing performance is part of the series dedicated to physical suffering inflicted for the purpose of releasing important energies through pain, in which she tried to portray how ideology acts on the individual’s body.

Raša Todosjevi?’s conceptualism appears especially in the well-known happening entitled “Was ist Kunst, Marinela Koželj?”, in which the artist obsessively repeats this question, creating an effect which is doubled by physical aggression directed towards the character being inquired. The question – fundamental for an artist – remains without an answer, and the brutal and manic manner in which it is asked makes reference to the repressive techniques used by the dictatorial regimes.

In 1970, after Czechoslovakia’s invasion by Soviet tanks, when the hope for the development of a more relaxed political system fell in, Koller created his own aesthetic system, critical towards modern society. He conceived a system of objects which he named UFO (Universal Futurological Orientations), an anti-illusionist anti-painting and anti-happening “realistic” concept inducing the idea of uncertainty about the future and operating with pseudo-scientific irony. He created a series of “anti-happenings,” photographs featuring the artist as a ping-pong player, equipped with a bat and the well-known white balls, in the most unexpected places, such as an attic window.

Belonging to the second generation of actionists at the end of the ‘70s, Jiri Kovanda made a series of minimalist happenings or happenings similar to those of the Fluxus movement, with obvious utopian aims. These happenings express the artist’s position/attitude, rather than his aesthetic research; due to minimalization and their ephemeral character, these happenings also had a therapeutic function, expressing a survival strategy.

For a group of artists belonging to the space of ex-Yugoslavia, the search for identity is synonymous with the relationship between politics, society, and the individual: “the body of the nation” can be found in countless individual bodies marked by ideology. Their criticism is primarily addressing the impact produced by the encounter between two types of “monocultures”: the Balkan one, ideologically oppressive, xenophobic and patriarchal; and the one dominated by western feminism.J. Stokic, “Un-Doing Monoculture: Women Artists from the ‘Blind Spot of Europe’ – the Former Yugoslavia,” ARTMargins, (2006) https://www.artmargins.com/content/feature/stokic.htm.

In different periods and situations, these women artists criticized the two cultural stereotypes as they tried to define something of an individual identity devoid of ideological approaches.

As Jovana Stoki? pertinently notices, the Yugoslav socialism was an original combination between communist ideology and consumerist elements in perfect cohabitation. The criticism of artists in this region also addressed this contradictory reality; thus the Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovi? created several series of works analyzing the connections between an individual and a “standardized” identity, the latter being perfectly illustrated by fashion magazines, with advertisements for various cosmetic products. In the 1975 series “Double Life,”Sanja Ivekovic, Personal Cuts, hrsg. Silvia Eiblmayr, Galerie im Taxispalais, Triton, Wien, 2001. in search for her own/ a feminine identity, the artist exhibits photos published in fashion magazines alongside with her own photographs, trying to “imitate” the models’ postures. Bringing together the two types of images reveals this restless search for identity, the questions the artist asks in her effort to define her femininity, as well as her individual identity.

In the same effort of questioning various identities in relation with the past, Sanja Ivekovi? repeats many years later, in 2000, this theme in the series entitled “Gender XX” and borrows from fashion magazines various images of models of impersonal and standardized “beauty,” but also transmits the idea of luxury and voluptuousness, on which she prints the names and details about some anti-Fascist female militants, communist heroines. The information about them is limited to announcing in a dry manner the young age when they were executed or committed suicide as soon as they were caught.

Sanja Ivekovi?’s preoccupations are directed more towards feminine, intimate themes. In the happening entitled “Inter nos,” she communicates with the public – from whom she is separated by a transparent surface – with the help of a screen. This happening focuses on the isolation and confinement the artist is trying to surmount by establishing a rapport with the audience.

The problem of national identity is more and more acute in the case of a number of artists belonging to the young generation who were dramatically affected by the wars in the ex-Yugoslav space. For Milica Tomic, the national identity becomes the central theme in a video performance where the artist presents herself smiling and proclaiming countless identities in as many foreign languages (“I am Milica Tomic, I am Dutch, etc”); however, in the meantime, many blood stains appear on her young body, leaking out of numerous invisible wounds. This performance reveals the association between the idea of national identity and the wound (the result of the imaginary guilt of belonging to a certain nation), with directinnuendos to the trauma caused by the Serbs’ nationalistic pathos in the recent years.

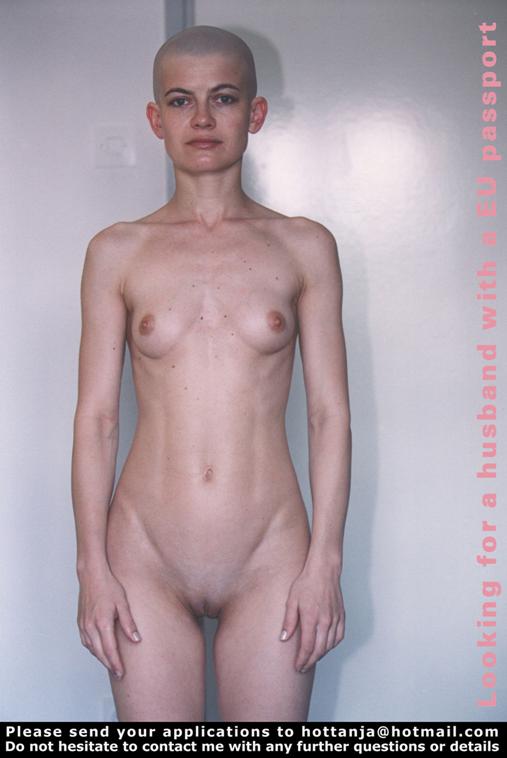

At the same time, another artist, Tanja Ostoji?, adopts another, radical type of research on national and individual identity. In the interactive project “Looking for a Husband with EU Passport”, the artist develops this idea in multiple ways: on the one hand, a strategy of self-rescue from the Eastern ghetto, on the other hand, a case study about sexes and the relationships between them. She uses her own naked body, purified of hair – breaking thus religious taboos – as a mediator between private space and public space, deliberately creating a form devoid of seduction and sensuality, a simple “tool” in the meditation process. Branislav Dimitrijevic expresses an interesting opinion about her performance, according to which the artist chooses to represent herself as a sort of “living picture,” not a “living sculpture,” but rather a “living monument” or even a “ready made”.

Tanja Ostoji?, “Looking for a Husband with EU Passport”. Courtesy of the artist.

Offering the image of her own naked body on the World Wide Web, she transforms it into a social body communicating with the people around with the help of the Internet. Launching a “search” offer on the site – an offer that mocks current match-making or sexual ads – Tanja Ostoji? received several replies accompanied by short presentations from a number of candidates. Using the Internet, a fast and global means of communication, contradicts the idea of confinement or ghetto and is used by the artist as a way to fight against isolation while her country was isolated from the rest of the world, and the population was confined in this given space.

During a later stage, the artist selects the marriage “offers” and organizes the first date with her future husband, accepted after the “selection,” the German artist Klemens Golf. This first date was public, and the theme for discussion – marriage – became a public/private topic of conversation. In Tanja Ostoji?’s interpretation of Lacan’s psychoanalysis, through marriage the man undertakes an active role in the public space while the woman only has a passive role, that of an object of the man’s desire. In her performance “Looking for a Husband with EU Passport,” she both demonstrates and undermines this role assigned to the man. Even if she uses her publicly presented body as an object of desire, as a result of her “selection” of the man chosen for marriage, Tanja changes the meaning generally assigned by the above-mentioned theory.

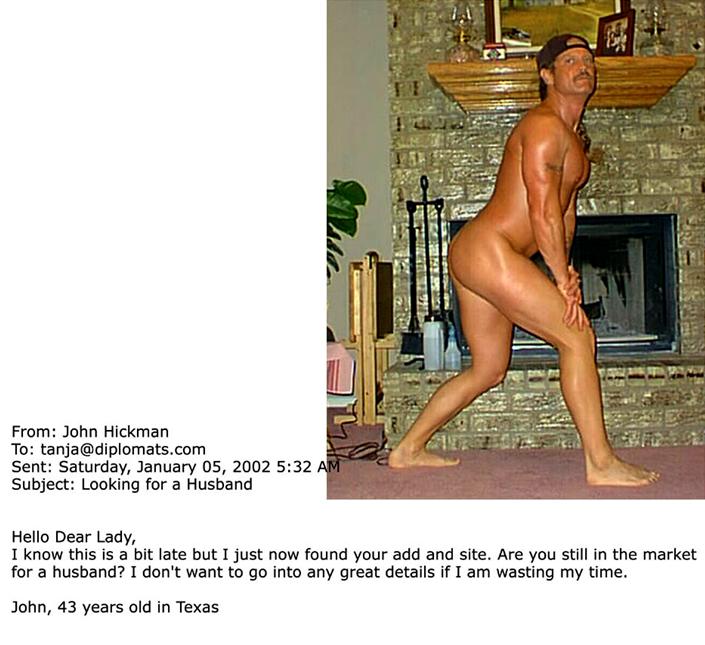

Response of John to Tanja Ostoji?’s project, “Looking for a Husband with EU Passport”. Courtesy of the artist.

Attempting to confront the stereotypes about people’s sexual identity, Tanja Ostoji? analyzed the system of power and relations at work in the world of contemporary art as well. In 2002 she put on the web the serial project “Success Strategies: Holidays with a Curator,” in which she had pictures of herself taken on a beach just as stars appear in various paparazzi’s photos. She represented herself as a young artist, at the peak of success, near a male curator symbolically representing power in the system of contemporary art institutions. In this series of performances, she publicly declared that a woman artist’s success was the result of a relationship of seduction with a male curator. This series had been preceded, in 2001, by “Black Square on White and I’ll Be Your Angel,” a performance in which Tanja Ostoji? became the “escort” of the main curator of the Venice Biennial, Harald Szeeman. Playing the role of a “guardian angel,” Tanja appeared in public in his company during the opening festivities as a woman of the world wearing “haute couture” outfits and finding herself in the middle of everyone’s attention, next to the most wanted and admired character, the curator of the biennial.

The Body of the Artist and Romanian Society

In the contemporary period it is the artists who, in their self-oriented and society-oriented discourse, discuss and reveal numerous possible identities. In communist totalitarian societies the artists, through their projects, systematically opposed the abolition of identities and enforced equality and instead militated for the freedom of expression, the assertion of the individual as such with his own identity undistorted by ideological pressure.

It is especially for those communist societies that the artist’s body as a carrier of signs appears as an identity problem of the subject and a social construct. A taboo theme, the body becomes a “material” handled by the artist in a social construction transfiguring nature. But the presence of the body in its unequivocal reality becomes subversive in a conservative totalitarian society.

In the Romanian context, an open approach to the body and an analysis of its language with everything this subject implies – nakedness, free bodily expression translated into gestures, sexuality, a meditation on genres and their relationship – meant breaking the taboos cultivated by this conservative society that would rather keep silent about an entire philosophy related to the body. The socialist Romanian society of the period cultivated – just like other dictatorial societies along history – the image of the “classical body” embodying an ideal of beauty and perfection best represented by the athletic body of sportsmen. In fact, their physical “demonstrations” in huge collective shows on stadiums offered a referential model for the entire society and became a free or imposed source of inspiration for the traditional artistic representations conceived in the so-called “realistic-socialist” style.

From this perspective, the artist’s naked body appeared as a way of flouting the norms and the official order, a challenging representation whose “dim” meaning had to be eliminated. Thus the censorship functioning in the institutions that organized exhibitions rejected anything that could arouse the suspicion that it did not obey the norms imposed by the state. Under these circumstances, the exploration of the body and its language of nakedness became genuine “heroic gestures”, equal to a political engagement, a reaction against the official position. This peculiar situation, quite different from the “liberal” socialist countries (ex-Yugoslavia, Poland), led to the isolation of the artists who experimented with body language and deprived them of the right to express themselves in public.

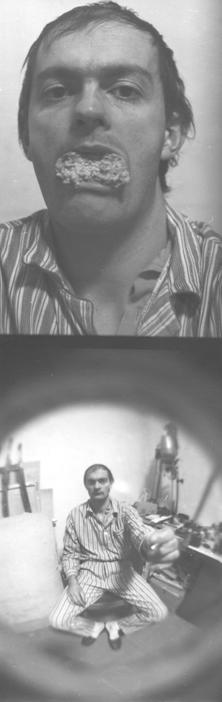

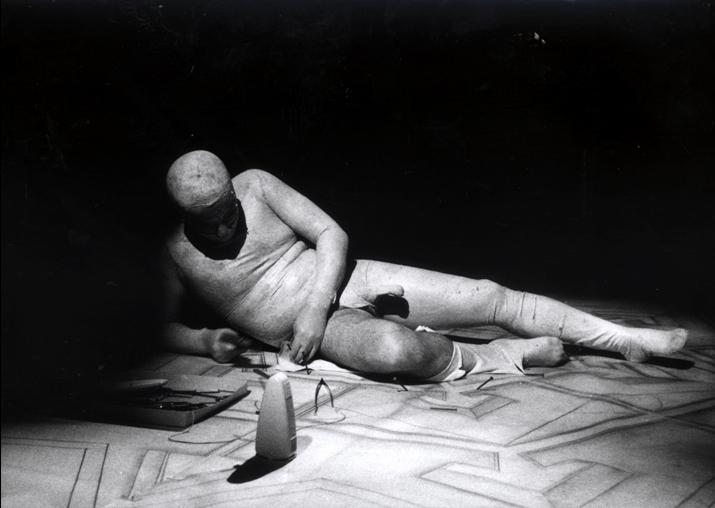

Ion Grigorescu, “In Prison”. Courtesy of the artist.

The central figure of this research related to the body in the ‘70s is undoubtedly Ion Grigorescu.I. Pintilie, Actionism in Romania During the Communist Era (Cluj: Idea Design & Print, 2002), 63 and ff. Starting from his interest in the world and the people, he devoted himself to some research focused both on the human psychic and on society, experimenting on his own body. In his artistic search, he tried to find an answer to the questions about identity that each and every one of us wonders about at a given moment. In a series of performances set before the camera, Grigorescu experimented with the loss of individual identity and of the intimacy of space during the communist period; he used a superangular lens made by himself, which focused on the image like a sight. With it, the artist manipulated the image, suggesting an “external” look, focusing on an indoor space and violating its intimacy.

Ion Grigorescu, “In Prison”. Courtesy of the artist.

The sight seems to be a “surveilling eye” transmitting the confusing and dismaying image of a “docile body” caught in the middle of a physical exercise reminding of imprisonment “rituals”: a salute, drills, or the enforced gesture of swallowing some simple food (“In Prison,” 1978). The indiscreet look oriented towards the inside of the apartment, together with this docility of the body, which, even in its intimate rituals, seems to obey the invisible commands of power, are a metaphor of daily life during the dictatorship, when, in the “dormitory-blocks,” the inhabitants’ lives were easy to control. In those enclosed spaces, through enforced discipline, a “docile body” was shaped on which pressure was exerted every second.

The disappearance of private space and the individual’s intimacy was characteristic of that period, an important stage for the dictatorship in building the “new man,” a fearful hybrid whose personal and collective memory has been annihilated. This was one of the themes used by the artist and repeated in some other performances, such as “Body Art inside the House”. Here the angle of watching introduced indiscreetly is also superangular; the image records the nude body caught in a moment of intimacy, relaxed, watched with the “coldness” and objectivity of a surveillance mechanism. In the sequences of the photograms, the image gets closer gradually, first showing the torso, then the chest, and finally only a detail of the face in an action of fragmentation.

But most of Grigorescu’s performances in front of the camera were devoted to the exploration of the “forbidden body” unanimously considered a taboo subject in Romanian society. On the one hand, he was interested in the exact recording of his body at a given moment as an expression of absolute nudity and intimacy often in relation with the intimate space (the room), which was given anthropomorphic features. On the other hand, he experimented with the recording “visual mechanism” by placing the camera in the most unexpected angles and positions, sometimes giving the impression of aggressiveness against the image.

In “Self-portrait with Mirrors,” a performance dating from 1973, repeated in several variants, Grigorescu used two moving mirrors that created a multiplication of the character, an amplification and dynamization of the movement. Very keen on experiments connected to the body in search for individual identity, the artist considers himself a maniac voyeur in search for the illusion produced by the virtual, this search leading him to a genuine psychic excitation, a restlessness that engenders other optical settings. In the photo action “Overlappings”, Grigorescu used chaotic multiplications of his own body with the help of the mirror but also with the help of superprints on the same frame of colored film. The effect was one of confusion, doubling multiplication, and false reflection, which the artist regarded as the desired result.

Searching for and experimenting with individual identityleads the artist to research about sexual identity – a vast and ambiguous theme, especially in the political context of that period. He tries to remake the lost unity of the original being – the androgyne – in the 1976 film “Masculine-Feminine”; the camera covers his own body, recording at the same time the space of the studio which becomes a receiver engaged in dialogue with the body as does the façade of a house nearby. A game of ambiguities, an exchange of fixed poles are also at stake when masculinity and femininity are perceived in relation with the body as such. The film proposes an even crossing of the surfaces of a passive body (the artist’s of course) lacking any expression or attitude, alternating with the crossing of the space of the studio or an external piece of architecture where the femininity of the body is a verified hypothesis. The film also launches some hypotheses and some research on the body in connection with space, but the main issue remains that of sexual identity.

The problem of sexual identity and the androgyne – the result of looking for and finding the two reunited poles – can be traced in the 1977 series of photographic performances “Birth.” Pushing this idea further, the artist creates a typically feminine situation experimenting with the transgression of a natural state and evoking pregnancy, giving birth, and lying-in on his own body. The series concludes with the appearance of the human figure in fetal posture. Thus he tests the artist’s capacity of surpassing the taboos imposed by the conservative society and its cliché-images about the two sexes.

Ion Grigorescu’s body-related research was not unique, but interfered in the 70s with Geta Bratescu’s preoccupations;I. Pinitilie, “Hypostases of Medea – or about Ignored Womanliness. Notes on Some Representations” in Contemporary Romanian Art, in Treca. Casopis Centra za ženske studije, Zagreb, vol. 2. (2000): 171-175. the woman artist was constantly interested in defining a feminine identity without tackling, however, the issue of the thematized body. She wonders about a locus of this identity in a series of textile collages dating from the 80s, entitled “Medea’s Portraits.” She dedicates her work to Medea, a controversial and feared mythological character, a combination between a witch and an ordinary woman. Due to this character’s final solutions, her tenacity in pursuing her plans, her strength of character, her initiatives and decisions, she brought upon herself disapproval and disgrace, becoming the symbol of outraged femininity, a woman whose life expressed repudiation and abandonment. “Medea’s Portraits” thus become internal feminine “states of mind,” a dazzling sequence of such states the artist appeals to by hiding the truth in mythological vagueness. These “portraits” illustrate the destruction of the codified patriarchal image of femininity. Not accidentally, the use of the textile support and the creation of those collages with the help of the sewing machine are an ironic comment on “feminine” materials. In parallel, Geta Bratescu devoted herself to research on her body as an identity object specific for representation, being one of the few artists who studied the relation between the body and the intimate space; the studio is regarded as a topos with anthropomorphic features bearing the size of her own body, an intimate space that becomes a sort of “alter ego.”

In a series of photographed or filmed events, she subjects herself to an imposed fragmentation symbolizing a substitute representation. In “Towards White” (1976) the artist is in her studio, gradually transformed into a stainless space by covering the walls with large sheets of paper. In the end she covers herself withpaper, painting her face and hands white and hiding in an attempt to identify with the space in order to erase the details of herself behind the mask. Continuing the series of photographs previously initiated, she creates “Self-portrait towards White” in a similar context: the image of the face regarded frontally is gradually hidden more and more conspicuously by covering it with a transparent film that grows more and more opaque, alternating as if in a challenging game of revealing and hiding the identity.

The same motif of the mask is repeated many years later in a new context that becomes more symbolic and expressive in the video recording “The Earthcake,” made in 1992 together with cameraman Alexandru Solomon and presented at the mixed-media exhibition “The Earth” in Timisoara. In a sequence of these images, the preparation of a “cake” of earth is narrated. During the film, the “characters” are the two working hands – selecting the soil and moisturizing it. Finally the artist appears wearing a white mask and a silver helmet on her head, swallowing, with solemn gestures, this earthcake in a ritual of taking possession and identification. In this case, the mask appears as a manifestation of the unmovable and universal self, giving it an unreal aspect and suggesting the transgression of daily time and space. The communication with the profound archetypal strata deciphered in this video performance is surprisingly similar with a performance by Cuban artist Tania Bruguera; in the happening “El peso de la culpa,” the artist is eating earthcakes mixed with salty water in a gesture of identification with Central American aboriginal populations and of a rejection of colonial domination or its impact in this area.O.M. Viso, Ana Mendieta. Sculptures and Performances, 1972-1985 (Hirshhorn Museum Washington / Hatje Cantz Verlag., 2004).

The idea of identifying herself with her own image or evoking the whole with the help of a part of it is repeated in the 1977 film “Hands,” with the subtitle “For the eyes my body’s hand remakes my portrait.” This identification is based on an association of images, hands, and eyes, which, deciphered with the help of psychoanalysis, can act as substitutes for each other. Therefore the evocation of the hand is the equivalent of a hidden self-portrait. The hands are drawing gestures of taking over, self-referential gestures, which also have a degree of generality.

In a later dialogue in 1993, Geta Bratescu remakes the experiment in “Hands” in a video entitled “Automatic Cocktail.” The evocation of the artist’s person in absentia or by substituting her entire person with her hands recalls the same principle in this short film: in the artist’s studio, among jars with brushes and paints, it is only these hands that are visible, working or sketching a human face; the performance is constantly interrupted by the gestures of the hand repeatedly and automatically hitting the arms of a chair. The artist’s hands and the studio thus define a “physiognomy,” evoking the whole image she identifies with at its most profound level – the creation.

As we have seen, the feminine identity – just like any other individual identity – is blurred in the public space during the communist period until it almost disappears, withdrawing as if to an ultimate shelter in the private space of the studio – in Geta Bratescu’s case – or in that of the apartment – in Lia Perjovschi’s case. The performances in front of the camera made at the end of the 80s – among which the most significant in this context seems to be “The Test of Sleep”A. Perjovschi, Catalog, Idea, Cluj, 1996. – emphasize a “vegetal body” exposed to sight, a body bearing a text inscripted on the skin. This “inscripted” body, carrier of more or less intelligible messages, loses its own significance in order to become a support-surface, a depersonalized object with no identity. The desire to communicate achieved through graphic signs does not achieve its goal; on the contrary, it becomes impossible, suggesting the loss of meanings, falling into muteness and sleep identified here as a pre-conscious state characterizing the condition of Romanian society at the time. On the other hand, if action is generally considered an attribute of masculinity, the passiveness of the revealed/exposed body suggests the traditional attribute of femininity; the apartment becomes a “shell” that protects from the brutal invasion of political power in the intimate life, a sort of a “uterus,” the only shelter and space where self-assertion is possible, while the public space is inaccessible.

Romanian artists have been greatly concerned with and have made a comment in their work on certain stereotypes that have become “common places” in the mind of most people. Teodor Graur, for example, has shown his interest in the typology of the “macho” man who exhibits his half-naked body in order to show his muscles and tattoos, an expression of his belonging to a subculture.

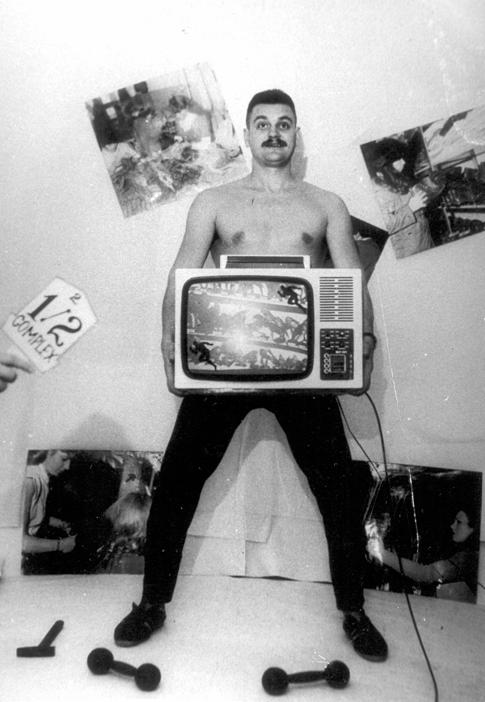

In the action entitled “The Sports Complex,” carried out in 1988 at House party in front of the camera alone, he performed as a young man from the “working class,” holding a functioning television set that showed one of the regular programs, with pictures of busy workers in the background. In the performance he did lift-weighting exercises, therefore highlighting the cliché of the “new man”, a socialist product brainwashed with clichés in which he naively believed. The pun in the title of the action, “The Sports Complex,” is ironic and relies on the ambiguity of the word “complex,” which may refer either to a group of buildings or to a psychological state of inferiority that causes behavior problems.

Teodor Graur, “The Sports Complex”. Courtesy of the artist.

Along with the fall of the communist system after 1989, the centralist state lost its hegemony, making way for the assertion of the numerous identities censored for so many decades, especially in the context of the erosion of the frontier between public and private. In the Romanian post-communist society, many debates took place around the topic of ethnic or religious identity. The artists were the first who had something significant to say about this, playing in a way the role of mediators within the society that found it difficult to regain its right to an opinion. Thus the doubts about collaborating with the secret police in the case of many citizens or the expression of distrust and dissatisfaction about the self in relation with a genuine identity hidden during the communist period gave birth to aggressive performances where the artists’ metaphorical expression contained a series of individual truths with a social relevance that was difficult to express in public. In these types of staging the body remained the artist’s privileged material.

In the performance entitled “Throwing away the Skin,” Alexandru AntikThe action took place during the Zone 2www.zonafestival.ro). Festival, Timisoara, 1996 ( exorcised “the evil” in every individual in front of the public and proposed a symbolic purification; he started with difficulty to select and cut a synthetic skin – a cover that could be considered his double – and secured it with nails, a gesture that was equivalent to exorcising the evil in an individual and, at the same time, collective ritual, an action of metamorphosis and transfiguration taking place in the even and exasperating rhythm of a metronome. Under the pressure of the present time and space, symbolically suggested by a circle inside which the artist placed himself, Antik condensed in a dramatic way “the liberation” from under the pressure of an oppressive past and the symbolic regain of the lost identity.

Alexandru Antik, “Throwing away the Skin”. Courtesy of the artist.

The “reality” of the body, which bears the signs of old age and represents a sort of automaton that executes various actions as if they were empty daily rituals, was analyzed by the same artist in the 1997 action, “Afternoon Oscillation.” Together with a feminine character, with a white, clown-like face, whose faded individual features were meant to plausibly suggest the human condition, the artist appeared suspended from a cable, gently swinging in the air, accompanied by music specific to fairs, and performed in a short absurd dialogue, similar to the ones in Eugene Ionesco’s plays.

The theme of the double and the liberation from the negative accumulations of the previous period can be found after 1989 in a series of public performances by Lia Perjovschi, among which we can mention “State of mind without a title” and “I fight for my right to be different.”During the Zone 1 Festival, Timisoara, 1993. The former is a street performance action dating from 1991, when the artist carried on her back a sort of “double,” a “shadow,” made from paper. This indefinite object, which was the size of her body, played the role of emphasizing a hypostasis of the body determined by the human mind – the problematic split of the human personality, and the artist used it in an attempt to develop the theme of the dark mental “inheritance” that affected many people at the time, as well as the theme of split personality.

Analyzed from the perspective of the moment when it took place, in 1993, the latter performance appears as a criticism addressed to the entire post-totalitarian society in search for its identity. The unproductive idea of annulling identity and enforcing equality is opposed by the desire for free expression and the artist’s own search in defining this individual identity. The entire happening is focused on the theme of the double – an immobile full-size puppet made of rags, on which she manifests her affection as well as her aggressiveness; the artist thus alternates the tender gestures of putting on the doll’s clothes, placing it in a position similar to hers, as a faithful copy, with fits of anger manifested by throwing the puppet into black paint and then against the walls or even against the spectators. These fits are again followed by tender gestures, when the artist lies down near her immobile double, imitating it in a gesture of self-mirroring and introspection with an unexpected dramatic effect on the public. Consequently, in the two actions emerges the theme of the double, which may also be interpreted as a “split” of the artist’s personality and of her creation, as a crossing of the border between these two fixed poles, which shifts the focus onto the subject / author.

Working for a long time in relation to “the couple,” Gusztáv Ütö, together with a female partner, is in search of an identity defined with difficulty in the context of transition. The questions about identity address appurtenance and determination – on the one hand, gender identity (and here the theme of the couple is meant to establish the importance of every part as well as of the whole), on the other hand, local and regional identity versus national identity. Belonging to the Transylvanian Hungarian community, the artist tried to determine these identity nuances along a series of festivals organized by himself by the Lake Sf. Ana, but also in his own performances. The numerous requests for the self-definition of the community were amplified by other artists who contributed their own nuances to the already frequent themes. Among the favorite themes, we can mention the bipolarity (masculine/feminine, black/white, strong/weak, etc.) or the theme of Transylvanian Hungarian identity evoked by specific proverbs, cliché-images in contrast or confronted dynamically with a larger national identity.

Immediately after 1990, the re-discussing of the much debated national identity combined with the negative cliché-image of the country abroad determined Dan Perjovschi to organize a performance with dramatic and parodic character at the same time: tattooing the name of the country – RomaniaThe action “Romania” also took place during the Zone 1 Festival, Timisoara, 1993, while “Removing Romania” was dedicated to the same festival in 2002, but actually carried out within the “In der Schluchten des Balkan” exhibition, on view at Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel, 2003. – on one shoulder. This “antiperformance,” unspectacular for the public, in which the artist subjected himself willingly to a branding action, reminding one of concentration camps and the confrontation with the loss of one’s own identity by the brutal regimentation under the name of a country, was one of the most sincerely desperate forms of manifesting a post-December trauma, a form of protest against a “collective amnesia” manifested by the general indifference for the great problems which remained unsolved during the transition from communism to another stage. Through this performance, Perjovschi acknowledged and accepted his own national identity as a stigma.E. Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963). This performance was repeated ten years later in “Removing Romania,” where the artist subjects himself to surgery having the tattoo removed, “erased” with the help of the laser. In fact, the molecules containing the paint particles spread all around the body during this surgery, which is a form of dissemination of contents and message – the above-mentioned stigma appearing dimmer but not annulled to the viewer.

Dan Perjovschi, “Romania”. Courtesy of the artist.

In conclusion, the relation between the public and the private body is in tight connection with a public and a personal space. The body may be considered the expression of interiority and intimacy, which is best achieved within personal space. But, as Bachelard states, from the perspective of an anthropology of imagination applied to the self, interior and exterior space are two reversible concepts that interchange their “hostility” and meet on a thin borderline, on a surface painful to both of them. Thus the body may be considered the “painful surface” where interior and exterior space meet.

The projection in public space of the private body and of personal space, a risk taken only by artists, has the effect of a philosophical “upheaval,”G. Bachelard, “La poétique de l’espace” in La dialectique du dehors et du dedans (Paris: Quadrige, 2001). and the shocking and telling disclosures are meant to change the general perception, affected by conformism and “commonplaces.”

Both the private and the public body tell something about an identity or several identities – individual or collective – which they disclose and bring to the public conscience. In the contemporary context, of transition from communism to liberal societies, some of the most interesting problems in ex-communist countries are related to identity, encompassing the dilemmas of and the conflicts between multiple suppressed identities, which have been regained or altered due to changes in society. These changes, sometimes dramatic, determine the reanalyzing of traditional identities, as a result of the total collapse of a once operational value system.

This study was carried out as a result of a research grant offered by the New Europe College in between 2005 and 2006.

Ileana Pintilie is an art historian and art critic. Her books include Actionism in Romania During the Communist Era and the volume Mitteleuropäische Paradigmen in Südosteuropa. Ein Beitrag zur Kultur der Deutschen im Banat (with Roxana Nubert). She has also published many articles and essays on contemporary art in Romania and abroad in international catalogues and volumes. In 1994 Pintilie won a National Award for Art Criticism. Pintilie is a contributing editor of ARTMargins.

Ileana Pintilie is an art historian and art critic. Her books include Actionism in Romania During the Communist Era and the volume Mitteleuropäische Paradigmen in Südosteuropa. Ein Beitrag zur Kultur der Deutschen im Banat (with Roxana Nubert). She has also published many articles and essays on contemporary art in Romania and abroad in international catalogues and volumes. In 1994 Pintilie won a National Award for Art Criticism. Pintilie is a contributing editor of ARTMargins.