The Politicization of the Private, or the Privatization of Politics? A View of Recent Czech Art by Women

Focusing on Czech women artists working in installation, photography, performance, and sculpture, I want to explore the subversion of phallocentric paradigms in East-Central European culture and society from a feminist perspective. In discussing various historical, ideological and theoretical formations that have contributed to the discrimination of women, I will examine the reasons for the absence of an explicit political dimension in contemporary Czech womens’ art. I also want to draw attention to the alternative ways of marrying the personal with the political that have been developed by Czech women artists during this period of transition.

Focusing on Czech women artists working in installation, photography, performance, and sculpture, I want to explore the subversion of phallocentric paradigms in East-Central European culture and society from a feminist perspective. In discussing various historical, ideological and theoretical formations that have contributed to the discrimination of women, I will examine the reasons for the absence of an explicit political dimension in contemporary Czech womens’ art. I also want to draw attention to the alternative ways of marrying the personal with the political that have been developed by Czech women artists during this period of transition.

Czech women artists frequently politicize female privacy and domesticity without appropriating direct political statements from the vocabulary of political propaganda. The slogan that “the private is political” has accompanied the feminist movement from its very beginning. The politicization of the private sphere became a way of confronting a social and cultural system that excluded women by labeling them as representatives of the domestic sphere or as the demonic agents of an uncontrolled sexuality. Western civilization is based on the gendered opposition between culture and nature. The social terrain of Western civilization is divided into the private sphere (traditionally belonging to women), on the one hand, and the public sphere (belonging to men), on the other. This dichotomy has for centuries prohibited women from playing an active role in the public life of society.

In the past (in many places even today), Czech women could not become social or political subjects to the extent that they were economically dependent. They were granted a limited private sphere of influence where they could exert their (moral) authority. Thanks to this restriction, women have received only little ideological support from recent feminist art and literature. And the price for even this minimal support was their all-out submission to dominant Western definitions of femininity.

It is apparent that if art made by women is to enter the public realm, and if it is to rid itself of common stereotypes, it is crucial to rethink the existing socio-cultural norms which constitute the norms of male dominance, despite the fact that they are being defined as “universal,” “human,” “democratic,” or otherwise gender-neutral. The increasing number of women artists in East-Central Europe, including the Czech Republic and Slovakia, is remarkable, yet without a full revision of existing norms and canons it is hard to imagine that these artists could become fully recognized and understood. In this era of political, economic, and social transition it would be impossible to launch such a revision without at the same time considering it eminently political. As in any society in which historical developments have brought about rapid change, it would be unthinkable for an East-Central European woman artist to become an autonomous subject without understanding the political implications of the traditional mechanisms of historical subject-formation.

From the point of view of Western art theories and feminist art criticism, these things may seem obvious. In the post-totalitarian countries of the former Eastern Bloc, however, they are not obvious at all. Most Czechs (including professional art historians, critics and many artists) still conceive of the relationship between art and politics as something inappropriate or even sordid. In East-Central Europe, art is often still viewed as something transcendent, unearthly, and universal that exists apart from the banality of people’s everyday lives. It comes as no surprise that in order to accommodate women within the frame of “true” art, women artists are often asked to give up their femininity, to neuter themselves politically and otherwise, and to consequently to merge with those artists who float in an ahistorical and utopian universal space above any particular political and social issues.

In the Czech Republic, politically active art continues to be seen either through a totalitarian prism, i.e., as propaganda, or through the prism of the cold-war dissident experience, i.e., as an art of cryptic hints and metaphors. In East-Central Europe, politics is identified primarily with political parties, and the digression of politics into the male-dominated scientific, philosophical, and historical sphere is often frowned upon. After four decades of Communist propaganda, East-Central European societies are understandably suspicious of politics.

However insufficient they may seem, it is heartening to see that discussions concerning gender and otherness are gradually emerging among a number of contemporary women artists who question the representation of female (but also male) bodies. These female artists challenge the role played by the media in constructing oppressive images of femininity by practicing “low” traditional women’s art, as well as by questioning women’s rights and the role of the mass media in the proliferation of “femininity”. In order to rid ourselves of prejudices concerning the political dimension of art, it is as important to include feminism as it is important to lose our prejudice against Marxism. Politics, after all, does not have to be identical with the direct application of political slogans and ideologies. Instead it should be seen as a process of critical questioning that examines the universal “truths” around us.

A crucial question for my academic and curatorial work is the question who we are with reference to where we are, that is to say, where we are not only with regard to universal hierarchies, but also with regard to the environment we live in, to the language we use, and to the people with whom we communicate. At the end of the 1960s, Western Europe and North America experienced the first wave of feminism, challenging traditional artistic, critical and art-historical paradigms. During the same period, the countries of the former Eastern block experienced a brief moment of freedom. Even though the revolutionary and liberating events that took place in the former Czechoslovakia in 1968 carried a faint echo of the sexual revolution, the non-conformist discussions concerning issues such as freedom, autonomy and anti-repressive structures rarely includedsexual politics or feminism. These discussions were non-gendered because the freedom of the entire Czech and Slovak population was at stake. The fact that feminism was, in such a context, considered as being too concerned with particulars becomes understandable once we acknowledge the existential nature of this situation. During the oppressive twenty-one-year-long occupation of the country by the Soviet army that followed the 1968 “Prague Spring,” the absence of all gendered discourse became even more painful. Ironically, this “neutering” was effected both by the regime’s enemies and by the regime itself. To neutralize all difference between individuals, genders, ethnic and national groups was highly commensurate with Communist ideology. In real terms, however, it translated into sexism, homophobia, racism, and xenophobia. The situation in the arts reflected the situation in society at large. Even though there were some significant women artists on the Czech art scene, feminist issues remained almost unreflected. (One of the few exceptions here was Jana Zelibska, a Slovak sculptor, installation and performance artist.) To fight against the regime as “one man,” to use a telling Czech idiom, was much more important than to figure out the relationship between men and women.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s a number of remarkable Czech women artists appeared: Vera Janouskova, Adriena Simotova, Daisy Mrazkova, Eva Kmentova, and Zorga Saglova, among others. Significantly, all of them opposed the new regime that brought about “normalization” (In the former Czechoslovakia, the term “normalization” is commonly used for the post-1968 period, a period during which the so-called “anti-socialist” and “anti-revolutionary” forces were liquidated by the Soviet army together with the repressive local Czech government.) and that either forced them underground or totally prohibited their work. Until the collapse of the Berlin wall, these artists could not publicly show their work and their names were taboo in their home country. Since then, the work of these women has been exhibited, yet the very way in which it was interpreted betrays the critics’ continued gender bias and a disquieting tendency to flatten any “different” artistic originality. For example, the work by women artists who were married to artistically successful men was usually seen as secondary and imitative of their husbands. Those women artists (especially sculptors) who worked in more “aggressive” genres or used traditionally “male” (hard) materials were often characterized as “masculine,” another way of saying that in order to become real artists they had to suppress their female identity. On the other hand, the work by women artists whose artistic language was sensitive, “soft,” or that dealt with sexuality, domesticity, or family issues was likely to be considered handicraft rather than art. Good, “high” and valuable art was treated as the domain of men. (Incidentally, what all these women artists had in common was a total disinterest in having their work included in state museums and galleries).

When during the post-Vietnam era artist groups such as Guerilla Girls were busy organizing all manner of happenings, protests and discussion groups all over America, there were no organized public interventions by women artists in the Czech Republic. Women artists worked individually in their studios. Meanwhile the official “Communist Union of Women” happily derailed all efforts to liberate women. Facing the official propaganda of the Communist women’s movement, liberal women artists moved away from all group interaction with the public. If the idea that “political action can be a creative act” (Linda Nochlin) sounded absurd during Communist times, the opposite notion, i.e., that an artistic gesture can be a political act, was much more common. (The work of Milan Knizak, Petr Stembera, Jan Mlcoch, or Pavel Kovanda (all of them men) would be unthinkable outside of this frame of reference.) Nevertheless, women remained a rarity among performance artists whose primary concern was to enter the public sphere. The performances by Jana Zelibska, Zorka Saglova or Margita Titlova were exceptional cases in this context.

The work by Czech women artists during the postwar period lacked a political dimension, a situation that started to change only in the 1990s. Indeed, if we can agree to expand the notion of politics beyond the boundaries of political statements and propaganda, this lack turns out to be partly a fiction. For many Czech women artists simply understand politics in a way that differs sharply from traditional political discourse. They tend to reflect more subtle movements in society, history, family, language, or even in their own bodies, merging privacy and domesticity with politics and public space. What we are dealing with here is what I would like to call the politicization of the private, or the “privatization” of politics. I now want to examine the work of eight women artists, six Czechs, one Slovak, and one American, all of them living and working in what until 1993 was called Czechoslovakia.

Diets, Eroticism, and the Politicization of the Female Body

At the beginning of the century, Virginia Woolf predicted that it would take long before women would be able to tell the truth about their own bodies. In 1962, Betty Friedan quoted a young woman who wanted to reach a state of ideal beauty: “Lately, I have been looking into the mirror, and I am afraid that I am going to look like my mother.” In a world governed by film and advertising, universal beauty is fetishized There is an assumption that women should embody this ideal and that men should own it, an assumption that perpetuates male dominance while at the same time strengthening women’s desire to be perfect and admirable.

The female body whose visual representations in art history traditionally belonged to their male creators, has recently become the site for negotiating women’s identity and subjectivity, and for initiating a polemics with stereotypical ideas about femininity. The emphasis on bodily imperfection as we find it in the work of artists such as Veronika Bromova or Michaela Thelenova could be interpreted as an obsession with crude naturalism. However, this interpretation elides the subversive message these artists offer their viewers. Bromova and Thelenova argue that the social order oppresses real, three-dimensional women through the endless reproduction of their faces, voices, and bodies, their reductive transformation into beautiful and irresistibly seductive images. Bromova’s and Thelenova’s critique is mixed with undermining of the social and visual stereotypes that exploit female bodies.

The female body whose visual representations in art history traditionally belonged to their male creators, has recently become the site for negotiating women’s identity and subjectivity, and for initiating a polemics with stereotypical ideas about femininity. The emphasis on bodily imperfection as we find it in the work of artists such as Veronika Bromova or Michaela Thelenova could be interpreted as an obsession with crude naturalism. However, this interpretation elides the subversive message these artists offer their viewers. Bromova and Thelenova argue that the social order oppresses real, three-dimensional women through the endless reproduction of their faces, voices, and bodies, their reductive transformation into beautiful and irresistibly seductive images. Bromova’s and Thelenova’s critique is mixed with undermining of the social and visual stereotypes that exploit female bodies.

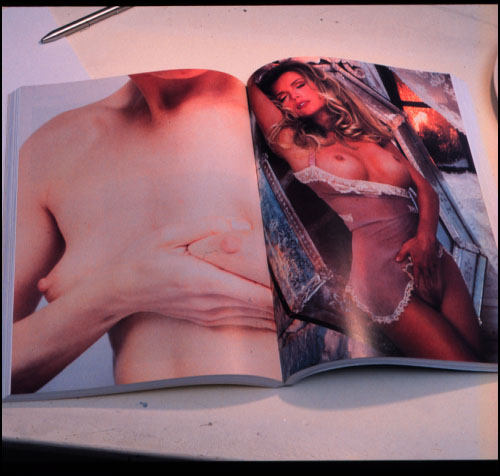

The gap between the ideal and the real is most explicitly examined by Zdena Koleckova in a project entitled “Playboy.” On a double page of the Czech art magazine “Labyrinth,” Koleckova juxtaposed the photograph of a masturbating blond sex-symbol in lace underwear with a picture of herself holding her breasts as if she was performing a self-examination for cancer. The unconscious fear of imperfection that haunts women as they confront the ideal proportions of the magazine models meets here the fear produced by medical statistics. Koleckova questions the ambiguity of visual imagery and shows that “looking” is less an innocent act than it is the product of a voyeuristic desire for power and ownership.

The gap between the ideal and the real is most explicitly examined by Zdena Koleckova in a project entitled “Playboy.” On a double page of the Czech art magazine “Labyrinth,” Koleckova juxtaposed the photograph of a masturbating blond sex-symbol in lace underwear with a picture of herself holding her breasts as if she was performing a self-examination for cancer. The unconscious fear of imperfection that haunts women as they confront the ideal proportions of the magazine models meets here the fear produced by medical statistics. Koleckova questions the ambiguity of visual imagery and shows that “looking” is less an innocent act than it is the product of a voyeuristic desire for power and ownership.

Barbara Kruger’s well-known phrase “Your Body Is a Battleground” has played an important role in the feminist art movement over the last thirty years. Even though we don’t have to understand this sentence in its original militant connotations, the history of figurative art, popular culture and commercials cannot leave any doubt that the body is political matter inasmuch as it has always been a site for powerful political, economic, social and cultural mechanisms.

Patriotism and Public Space

Another artist, Alena Kotzmannova, placed a miniaturized version of the Czech national symbol, the St. Wencle’s monument in Prague’s Central Square, in a transparent plastic shopping bag and photographed it in different locations all around the world. In order to “multi-culturize” the Czech national icon, the artist traveled with her replica wherever her nomadic life took her. After returning home, she displayed close-up shots taken during her travels at various tram stops all over Prague, accompanied by the slogan “Shopping is my hobby.” While appropriating the time-honored male icon signifying Czech national autonomy, Kotzmannova rebelliously “reduced” this major symbol of Czech patriotism. “Shopping is my hobby,” of course, hints at the current country-wide shopping mania: Kotzmannova transforms St. Wencle from being the messenger of national enlightenment and redemption into an icon of late capitalist ideology whose imperative is not to be, but to have.

Another artist, Alena Kotzmannova, placed a miniaturized version of the Czech national symbol, the St. Wencle’s monument in Prague’s Central Square, in a transparent plastic shopping bag and photographed it in different locations all around the world. In order to “multi-culturize” the Czech national icon, the artist traveled with her replica wherever her nomadic life took her. After returning home, she displayed close-up shots taken during her travels at various tram stops all over Prague, accompanied by the slogan “Shopping is my hobby.” While appropriating the time-honored male icon signifying Czech national autonomy, Kotzmannova rebelliously “reduced” this major symbol of Czech patriotism. “Shopping is my hobby,” of course, hints at the current country-wide shopping mania: Kotzmannova transforms St. Wencle from being the messenger of national enlightenment and redemption into an icon of late capitalist ideology whose imperative is not to be, but to have.

Kotzmannova chooses a woman to be the performing pioneer of this subversive transformation because in the 19th century, women had hardly had any opportunity to define the shape of the emerging Czech national identity. Incidentally, it is quite possible that Kotzmannova loves to shop, but that information is as irrelevant as the question whether the photographed person is in fact the artist herself. Kotzmannova’s eccentric, disobedient behavior deconstructs and problematizes an otherwise simple message. Instead of promoting national unity in the form of either a religious symbol or shopping mania, Kotzmannova asks the question who owns the Czech national identity, who has a moral right to “own” (and manipulate) the nation, and, last but not least, whether women really shop while men face the evils of this world.

Art for the Drawer

For years, Czech art critics and art historians have been of the opinion that ceramics is part of the decorative “applied arts”. This judgement had a degrading effect on the work of woman artist Jindra Vikova, which is informed by 1970s figuration. It is true that despite her formal originality and her unique touch of existential nostalgia, Vikova’s work usually addresses universal themes, such as the dialogue between people, envy, or human aggression, topics which have been confronted by many mainstream Czech artists from the 1960s to the present day.

On a recent visit to Vikova’s studio, I found a number of small collages and assemblages which use mirrors, aluminum foils, old photographs and cut-off fragments from old prints, newspapers, and magazines. When I asked her about them, the artist said she makes them just for her own pleasure during her free time, and that she usually doesn’t show them to visitors. She characterized these works as “drawer pieces” with which she has a very intimate relationship, but which she does not want to put on public display.

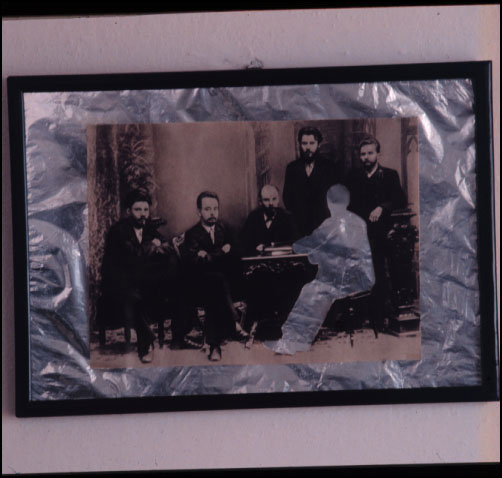

These modest, private works appear to be in open conflict with Vikova’s “public” style where universal themes are generally replaced by concrete events. Yet, despite their marginal role in Vikova’s work overall, these pieces touch on the essence of the artist’s personal experiences with the public. In these objects, Vikova makes important male personalities, such as Christ or Lenin, vanish from their old, dusty photographs and replaces them literally with a void. In a cycle of these drawer pieces entitled “History Otherwise,” the historical “greatness” of white men from the artist’s own family or from the glorious history of Western civilization, is met with silence and introspection. Just as women are continuously being erased from history, Vikova takes the scissors and “castrates” historical documents.

Vikova’s appropriation of political imagery in personal, hermetic rituals highlights the transformation of what goes by the name of women’s art. It shows that even the most intimate, vulnerable art can become a site for the loss of innocence, and that it can, both metaphorically and literally, hold a mirror to political and ideological discrimination.

Inscribing Women in History

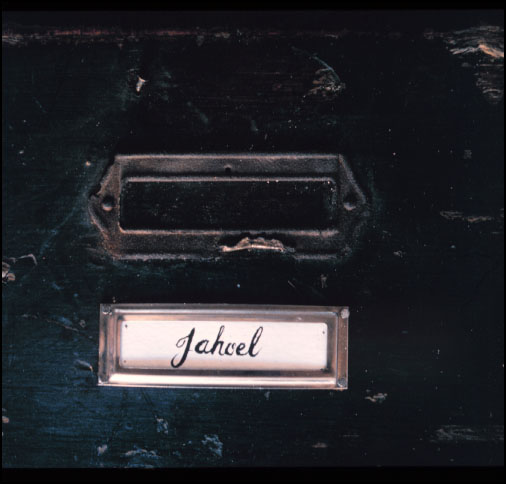

The opposite approach was taken by Barbara Benish in her piece for the group exhibit The Imagination of Pain which I curated in Prague’s Old Synagogue in 1996. Benish focused on the second floor of the building, a space that, according to Jewish tradition, was the only place in the synagogue that women were allowed to occupy. While examining the site some time before the exhibition started, Benish found a number of old metal frames that were traditionally used by Jewish women as receptacles for their name tags, assigning them a place during the service. Provoked by the exclusion of women from the main space of the synagogue and by the total disappearance of their names from the metal frames, Benish re-dedicated ten places on the upper gallery with new name tags, using women’s names from the Old-Testament. Through these names, the artist as it were re-inscribed the absent femininity into the site and its memory.

The opposite approach was taken by Barbara Benish in her piece for the group exhibit The Imagination of Pain which I curated in Prague’s Old Synagogue in 1996. Benish focused on the second floor of the building, a space that, according to Jewish tradition, was the only place in the synagogue that women were allowed to occupy. While examining the site some time before the exhibition started, Benish found a number of old metal frames that were traditionally used by Jewish women as receptacles for their name tags, assigning them a place during the service. Provoked by the exclusion of women from the main space of the synagogue and by the total disappearance of their names from the metal frames, Benish re-dedicated ten places on the upper gallery with new name tags, using women’s names from the Old-Testament. Through these names, the artist as it were re-inscribed the absent femininity into the site and its memory.

The exhibition The Imagination of Pain was organized around the themes of anamnesis and recollection, which are often driven as much by anxiety as they are propelled by desire. Ilona Nemeth, a Slovak-Hungarian artist who also participated in the show, based her project (“The Wall”) on the notion of space as the product of a lived sense of social position. Space, in Nemeth’s understanding, signifies mobility and visibility as well as anxiety and doubt. In one of the ground-floor aisles of the synagogue, Nemeth constructed a two-meter high minimalist U-form from unburned bricks, the kind of material that was traditionally used for building modest rural houses. Made from mud or clay, and containing a lot of other elements such as hay and tiny stones, these bricks not only have their own unique texture but they also emit an unforgettable smell. Although such bricks ceased to be used for house building long ago, so-called ecological architecture has recently rediscovered their merits.

The exhibition The Imagination of Pain was organized around the themes of anamnesis and recollection, which are often driven as much by anxiety as they are propelled by desire. Ilona Nemeth, a Slovak-Hungarian artist who also participated in the show, based her project (“The Wall”) on the notion of space as the product of a lived sense of social position. Space, in Nemeth’s understanding, signifies mobility and visibility as well as anxiety and doubt. In one of the ground-floor aisles of the synagogue, Nemeth constructed a two-meter high minimalist U-form from unburned bricks, the kind of material that was traditionally used for building modest rural houses. Made from mud or clay, and containing a lot of other elements such as hay and tiny stones, these bricks not only have their own unique texture but they also emit an unforgettable smell. Although such bricks ceased to be used for house building long ago, so-called ecological architecture has recently rediscovered their merits.

In Nemeth’s installation for The Imagination of Pain, these shapeless, clumsy bricks do not only imply a reference to nature but they also hint at thousands of exploited Gypsy workers in Slovakia. Juxtaposing the romantic ideal of a return to nature with the bitter experience of slavery, Nemeth created an obscure architecture within an architecture, stressing the division between inside and outside, public and private, free and dependent, “I” and “Other”. Being inside the brick structure, one felt both sensually aroused and painfully claustrophobic. The security of the quasi-architectural interior quickly turned into a threatening seclusion from the world. If a discourse of the self is possible only in terms of the “Other”, how can we cross the boundaries of difference without creating new boundaries? How can those who are excluded and marginalized become subjects if they remain invisible? Can a painful psychosomatic experience become a turning point in the search for identity? “The Wall” challenged the geographical organization of the social sphere, but it also sharply pointed out the ideology of inclusion and exclusion that is imprinted on our bodies and minds.

Transforming Aristotelian Aesthetics

The Latin preposition “trans” signifies the act of “crossing over.” Even though the prefix by itself doesn’t mean anything in English, Czech uses it commonly as a noun. To be “in trans” literally means to be “high,” in a state of extreme psychosomatic experience. (The term has also often been applied to female hysterics).

Since ancient times, Western thinking has been based on the great dichotomies that are the result of gender polarities. While the feminine is usually understood as an expression of passive physis, as an amorphous, soft, and submissive matter, the masculine is characterized by techne, an active, creative, and rational principle that produces a clear, scientifically verifiable form characterized by a claim to universality. In the Western tradition, the masculine principle transcends all that is immanent, unconscious, illogical, sensual, unknown, mad, or hysterical—in short, everything the same tradition associates with women. Male transcendence overwhelms female “trans-being”. We ought to perhaps rethink such existing aesthetic norms and search for innovative trans-forms and trans-materials. Soft, hybrid forms could signify our transition towards an existence “in trans,” an unconscious, sensual, even erotic production of shapes and objects that move slowly at one time and fast at another and that, even where they enter the public sphere, provoke laughter as well as pleasure.

Since ancient times, Western thinking has been based on the great dichotomies that are the result of gender polarities. While the feminine is usually understood as an expression of passive physis, as an amorphous, soft, and submissive matter, the masculine is characterized by techne, an active, creative, and rational principle that produces a clear, scientifically verifiable form characterized by a claim to universality. In the Western tradition, the masculine principle transcends all that is immanent, unconscious, illogical, sensual, unknown, mad, or hysterical—in short, everything the same tradition associates with women. Male transcendence overwhelms female “trans-being”. We ought to perhaps rethink such existing aesthetic norms and search for innovative trans-forms and trans-materials. Soft, hybrid forms could signify our transition towards an existence “in trans,” an unconscious, sensual, even erotic production of shapes and objects that move slowly at one time and fast at another and that, even where they enter the public sphere, provoke laughter as well as pleasure.

Softening, trans-gressing, feminizing the hard-core, masculine politics of common sense as we know it from the media is not to give up political activism, a fact that is well-known to an increasing number of Czech women artists who struggle both with the painful legacies of socialism and with their own growing disillusion over our recent capitalist experience.