The Polish New Wave at Tate Modern (Film Review)

Polish New Wave, Kinoteka Film Festival 2009, Tate Modern, London, 3-5 April, 2009

As the title of this event implies, the Polish New Wave is by no means a straightforward pre-existing historical movement that can be precisely dated. In contrast to the FrenchNew Wave and the closer example – both geographically and politically – of the Czech New Wave, the Polish New Wave was never able to have a continuous, stable development but was rather evident in a number of individual cinematic projects occurring over an extended period of time, the contours, definition and limits of which are still subject to debate.

In fact the idea behind this screening program was directly inspired by a recent Polish film directed by the Polish contemporary artist Piotr Ukla?ski, Summer Love (2006), that explicitly set out to blur the boundaries between art and film and thereby continue the New Wave impulse discernible in Polish cinema from the 1960s to the present.This was clearly stated by the curators of this event and its earlier incarnation in Poland, ?ukasz Ronduda and Barbara Piwowarska: “The idea of situating contemporary inter-disciplinary artwork within the new-wave tradition has been further developed by the curators, serving as a pretext for the reconstruction of the history of the Polish New Wave – a phenomenon that never existed.”(Ronduda and Piwowarska (eds.) Polska Nowa Fala: Historia Zjawiska Którego nie By?o [Polish New Wave: The History of a Phenomenon that Never Existed]. (Warsaw: Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowskie Castle/Adam Mickiewicz Institute, 2008), 4-5. [back]) So the Polish New Wave is a retrospective construction, a concept that is both critical, creative and on a certain level ahistorical.

What does it mean to construct an ahistorical concept of a New Wave, a term that is usually applied to historically situated film movements? The preliminary answer given by the curators to this question is that it refers to a cinema that “examines and experiments with its own cinematic form.”(Ronduda, 4.) In particular, the curators are interested in the ambiguous domain between art and cinema that escapes the dominant discourses of both spheres. Of course this raises questions of inclusion and exclusion: what are the criteria for deciding what belongs to the retrospective construction of the Polish New Wave?

In addition, to the first film of Zanussi and the work of Konwicki that are excluded by the curators for their conventional narrative form, other examples of excluded works were Roman Polanski’s short films and his first feature, Knife in the Water (Nó? w Wodzie, 1962), the script for which was written by Jerzy Skolimowski who does feature in the retrospective, the films of Wojciech Has, especially The Saragossa Manuscript (R?kopis Znaleziony w Saragossie, 1965) and Sanatorium under the Hour-Glass (Sanatorium Pod Klepsydr?, 1973), and out of the ahistorical period, the excluded works consisted of the science fiction films of Piotr Szulkin from the 1980s which were directly inspired by the work of ?u?awski, whose On the Silver Globe (Na Srebrnym Globie, 1976) was the centrepiece of the retrospective. To paraphrase another project of Ronduda’s, there is no doubt room for one, two, three or more Polish New Waves, of which the recent retrospective is just one example.

In addition, to the first film of Zanussi and the work of Konwicki that are excluded by the curators for their conventional narrative form, other examples of excluded works were Roman Polanski’s short films and his first feature, Knife in the Water (Nó? w Wodzie, 1962), the script for which was written by Jerzy Skolimowski who does feature in the retrospective, the films of Wojciech Has, especially The Saragossa Manuscript (R?kopis Znaleziony w Saragossie, 1965) and Sanatorium under the Hour-Glass (Sanatorium Pod Klepsydr?, 1973), and out of the ahistorical period, the excluded works consisted of the science fiction films of Piotr Szulkin from the 1980s which were directly inspired by the work of ?u?awski, whose On the Silver Globe (Na Srebrnym Globie, 1976) was the centrepiece of the retrospective. To paraphrase another project of Ronduda’s, there is no doubt room for one, two, three or more Polish New Waves, of which the recent retrospective is just one example.

The first film screened, Grzegorz Królikiewicz’s Through and Through (Na Wylot, 1972), was one of the most challenging films, particularly since both the setting and narrative sense of the events portrayed in the film onlybecome clear at the end. According to Ronduda, who introduced the film, this is because Królikiewicz was one of the few Polish directors who was also a film theorist and based his films on a specific theoretical understanding of cinematic perception. His conception of cinematic perception is an existential and ethical one, essentially grounded on the idea that human experience is based on the construction of order out of chaotic and fleeting perceptions.

The first film screened, Grzegorz Królikiewicz’s Through and Through (Na Wylot, 1972), was one of the most challenging films, particularly since both the setting and narrative sense of the events portrayed in the film onlybecome clear at the end. According to Ronduda, who introduced the film, this is because Królikiewicz was one of the few Polish directors who was also a film theorist and based his films on a specific theoretical understanding of cinematic perception. His conception of cinematic perception is an existential and ethical one, essentially grounded on the idea that human experience is based on the construction of order out of chaotic and fleeting perceptions.

Thus Królikiewicz attempted in his films not to create this order for the spectators, but to present them with chaotic fleeting perceptions that are nevertheless organised in such a way as to be susceptible to this perceptual ordering process on the part of the viewer. To encounter a film like Through and Through is to face the challenge of having to reconstruct an orderly perception out of a chaotic influx of images. Crucial to this process is that it is not a purely objective one but one that concerns and implicates the viewer’s own subjectivity in a type of double cognition, at once subjective and objective, capable of transcending the usual limits of self-identity, which is simply an intensification of the psychic process that takes place during any film screening.

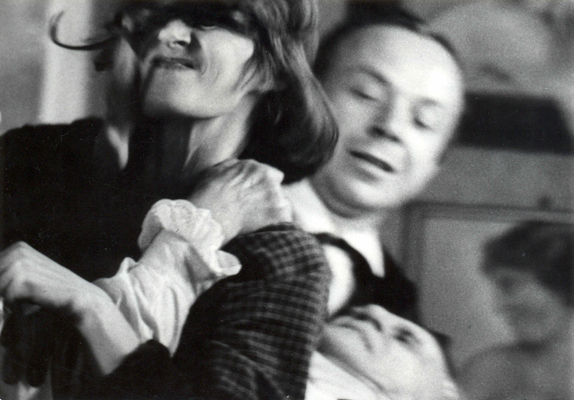

In practice this means that the resulting films contain gaps and are built out of fragmentary perceptions that suggest a whole without making it entirely available to the viewer; there is no omniscient god-like perspective on the events featured on the screen but merely fragmented perceptions taking place within the cinematic world that leave it up to the viewer to piece them together. Certainly Through and Through conformed to this idea from the beginning with a chaotic party scene in which a sleeping drunk (who only later turns out to be the central character) is bullied into playing the guitar and beaten when he refuses among the chaos of a drunken evening portrayed with an almost Warholian blankness and use of duration. Next the viewer witnesses a first communion, where our drunk, revealed to be a musician, is being fired for his drunkenness. All of the pieces of a linear narrative are present but still need to be precisely “articulated” by the viewer and this is how the film continues for most of its duration.

What is especially striking in the film is the use of extra-screen space; the key event in the film, when the main character and his wife beat up and kill an old couple, takes place behind a closed door, through which shouting voices and crashing objects are heard but not seen, as well as being suggested by shadows underneath the door, then the scene is shown through a rapid montage which makes the shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) seem slow and calm in comparison. This alternation of invisibility with hyper-visibility is perfectly analogous with the state of mind of the central characters’ experience, as testified by their later difficulties in reconstructing exactly what happened. As a viewer, one only realizes what happened after the fact, while the assailants are being tried for their crime. However, the viewer’s contemporary perceptions of the violence happening on the screen are visceral, involving the disorienting immediacy which connects the viewer with the assailants as well as the victims, and makes one share their existential space.

This perceptual disorientation interferes with the usual judgemental perceptions of marginal outsiders and it is precisely these judgements that Królikiewicz is critiquing in this film. Perhaps this film demonstrated the most radical use of techniques otherwise associated with the avant-garde and this is no doubt due to the director’s involvement with the avant-garde “workshop in film form” that involved such experimental directors as Józef Robakowski and Zbigniew Rybczy?ski, the latter of whom also worked with Królikiewicz as a cinematographer. Nevertheless, these techniques are deployed in a narrative context that blurs the boundaries between artistictechniques and narrative form. This narrative context gives these experimental techniques ethical implications that go beyond their deployment in the purely formal experimentation of the Workshop of Film Form.

The opening screening of the second day was Jerzy Skolimowski’s first film, Identification Marks: None (Rysopis, 1964). This film, along with the subsequent Polish films by this director, fit much better within the conventional understanding of the New Wave. Not only did Skolimowski make these films from the mid to late ‘60s, but they were explicitly acknowledged by French critics, and even Jean-Luc Godard, as belonging to the New Wave. From a formal point of view elements such as the use of available light, cinematically inventive shots, elliptical narrative and the documentary-like focus on the younger generation clearly resemble the French New Wave, perhaps more so than the films being made at the same time in Czechoslovakia. However, this New Wave “recognition” was a double-edged sword in that it was precisely this outside recognition and identification that Skolimowski’s protagonists, and by implication Skolimowski himself, since he frequently featured in his own films, was trying to avoid.

Identification Marks is a unique cinematic debut in that Skolimowski, rather than waiting for the opportunity to make a feature film after graduating from the National film school in ?ód?, simply designed all his film school exercises to be the parts of his first feature. After graduation, all he had left to do was to edit these pieces together to create his debut film. Whether impressed by the audacity of this procedure or the film itself, the “powers that be” then immediately gave him the opportunity to make a second feature, Walkover (1965) and both films were released the same year. This unique method generated a unique mix between amateurism and innovation that is evident from the first sequence of the film. Beginning in complete darkness, the room in which the main protagonist is sleeping with his partner is then illuminated briefly by a match which shortly goes out plunging the scene back into darkness while he asks her if she is sleeping. The scene continues in semi-darkness, illuminated by a fire, casting gigantic shadows onto a wall, by the street-light illumination, pouring in through the windows, and the pale light which enters through the door as the main protagonist exists the room. This scene, which is as choreographed as any street scene from European directors such as Fellini, uses very simple means to achieve dramatic effects, generating an entirely new way of perceiving the world of the protagonist and that of the society in which he lives.

The rest of the film concerns ten hours in the life of Andrzej Leszczyc, played by Skolimowski himself, starting with his appearance before a draft board and ending with his boarding a train to go off to military service.(3.10, the time of the train’s departure is a deliberate reference to Delmer Daves’ famous Western 3:10 to Yuma (1957).) This figure would, over the course of Skolimowski’s 1960s Polish films, become emblematic of the younger generation that found itself at odds with the imposed ideals of the Socialist state, its hypocrisy, corruption and especially the lack of possibilities for this generation to develop itself outside of a set of inherited rules of conduct. However, this rebellion is not presented in any cliché way but through the main protagonist’s apparent submission to military authority since, having successfully avoided military service for years through his supposed “icthyology” studies, he now makes no attempt to do so. As the film unfolds, this apparent submission to authority is shown to be a response and indictment of the emptiness and cynicism of Andrzej’s social environment; he would rather join the army, where there is no pretence of freedom than stay in a world that pretends to be free but in fact operates according to a set of suffocating constraints. Yet none of this is stated directly but rather emerges over a set of apparently haphazard wanderings and encounters in the city of ?ód?; nevertheless these encounters, as Tadeusz Lubleski has suggested, sum up the various phases of Andrzej’s life from childhood, to adolescence, to his interrupted studies, and to the various phases of his erotic experience.

Throughout all of this Andrzej is presented as an outsider, a complex figure at once seeming aimless and unmotivated and strangely compelling. This is perhaps because he embodies the anomie of being young and at odds with established society that has resonances beyond the Polish context to the worldwide youth rebellion that was bubbling under the surface of the mid 1960s and which this film captures in a “proto” or not yet fully articulated form. What is fascinating about this film is that it does this not so much through its content, which is in fact banal, but through its form, thereby transforming the seemingly accidental and meaningless experiences into a critical account of an entire society.

The next screening was a special event and perhaps the high point of the entire weekend. The showing of Andrzej ?u?awski’s rarely seen science fiction epic On the Silver Globe (Na Srebrnym Globie, 1988) in the presence of the director. This film was ?u?awski’s third feature and was mostly shot in 1976, before the authorities pulled the plug on the project, citing overspending as the reason. As the days went by, all the costumes, props, and other equipment necessary for the production simply disappeared. According to the director, the only reason a copy of the print survived was due to an anonymous female bureaucrat who kept a copy in a storehouse in Wroc?aw. Ten years later when as a perverse result of the imposition of martial law genre films – including science fiction films – had become acceptable and considered preferable to the films dealing with contemporary reality, ?u?awski was asked if he would now like to complete his film. With completion no longer possible for both artistic and technical reasons, the director instead compiled documentary scenes of contemporary Poland accompanied by his own voice-over describing the scenes that would have taken place at this time in the film.

The director entertained the audience with a few compelling stories during a light-hearted and good-humoured introduction to the film, concluding by wishing the audience good luck in their efforts to stay with the film for the entire three-hour duration and recommending vodka as providing useful assistance. The film itself defies description. Based on a science fiction epic written by the director’s great uncle Jerzy ?u?awski at the beginning of the 20th century, the narrative begins with the discovery of a “recording” of an austronaut mission to a new planet which they then proceed to populate. These recordings, which consist of a discontinuous collection of fragments that make up most of the film, chart the development of this new society thereby constituting something like a new book of Genesis as Ronduda has suggested.(Ronduda, 39.) Adding to this fragmentary and discontinuous series of recording are the insertions of the documentary scenes while the narrator describing the missing scenes. This functions to constantly interrupt any immersion in the narrative world and to forces the viewer to experience it for what it is, namely a fabricated mythology emerging out of the present, which the viewer is invited to co-create with the director rather than to simply consume a completed vision.

Once one adapts to the fragmentary style of the film, which predates other, less aesthetically radical uses of a video diary as a basis for narrative by more than a decade, certain tendencies emerge that show a process of cultural mutation or degeneration of the rational world-view of the original astronauts into a world of myths and rituals that seem to take on an increasingly violent and even militaristic character. The film very much operates at this level of the creation of myths that is also the creation of human society and therefore can be usefully compared to the theatrical and performative methods of Jerzy Grotowski’s theatre laboratory as Ronduda has also suggested.

However, while Grotowski’s theatre aimed to reveal a true, “good” humanity beneath the layers of artificial civilised behaviours, masks and armour, ?u?awski’s film espouses a much more pessimistic view of human nature in which the stripping away of civilised norms does not lead to any primitivist Garden of Eden but rather to a world of primal impulses, characterised primarily as forms of violence and cruelty rendering it a much more Artaudian vision than that evident in Grotowski’s theatre. It also seems to follow the Nietzschean idea that behind every mask is just another mask rather than an authentic self, which finds expression in the film through the ever-increasing tendency to adornment amongst the descendants of this new humanity.

Issues of cultural memory and transmission are also addressed in fascinating ways in the film not only by way of the transformation of the first settlers into mythical figures even apparently during their own lifetimes but also the repetition of human historical, biblical and mythical scenes such as battles and especially crucifixions which have a clear critical message in an overwhelmingly Catholic society (at this point in the film there are documentary sequences in one of Poland’s most important churches, the Mariacki church in Kraków, which serves to emphasise this). Apparently one of the reasons the script was approved in the first place was because it was perceived as having been anti-clerical. However, like everything else in the film, the exposure of religion’s cruelty is ambiguous and paradoxical and takes place within a wider critique of human nature in general. In its reference to genre and sheer ambition, the film goes well beyond the New Wave attempts at creating a new film language and depiction of contemporary society, so much so that it seems more to anticipate postmodernity and digital culture, while remaining at the same time rigorously poetic and aesthetically uncompromising.(In this light it is quite interesting to note that on the basis of this film ?u?awski was invited to Hollywood to read scripts by George Lucas imagining him to be likely to come up with the next Star Wars like epic. ?u?awski apparently used the money to acquire great works of literature; needless to say the world of ?u?awski’s cinema and new Hollywood are several universes apart!)

Given ?u?awski’s denunciations of the Polish Cinema of Moral Concern as a coup d’etat against cinema that was more a type of radiophony,(?u?awski paraphrased from Ronduda, 40.) it was interesting that the following screening was the film Illumination (Illuminicaja, 1973) by Zanussi, one of the key figures of the Cinema of Moral Concern movement.(This was an extremely well known Polish film movement taking place in Poland in the late 1970s of social realist dissident cinema associated with Andrzej Wajda, Krzystof Kie?lowski, Krzystof Zanussi and Agnieszka Holland that was a precursor to the Solidarity movement.) However, this film was from the earlier period of Zanussi’s work, which was heavily influenced by the French New Wave. In fact, he first became known through interviews and on set-reports from the films of some of the key figures of the Nouvelle Vague in the 1960s. Nevertheless, even these early films by Zanussi have tended to be seen in terms of their content rather than their form and thereby assimilated into the later movement that was perhaps sealed by Zanussi’s appearance in Kislowski’s Camera Buff (Amator, 1979) in which questions of social reality and engagement are prioritised by Zanussi, appearing as himself, over questions of cinematic form.

Given ?u?awski’s denunciations of the Polish Cinema of Moral Concern as a coup d’etat against cinema that was more a type of radiophony,(?u?awski paraphrased from Ronduda, 40.) it was interesting that the following screening was the film Illumination (Illuminicaja, 1973) by Zanussi, one of the key figures of the Cinema of Moral Concern movement.(This was an extremely well known Polish film movement taking place in Poland in the late 1970s of social realist dissident cinema associated with Andrzej Wajda, Krzystof Kie?lowski, Krzystof Zanussi and Agnieszka Holland that was a precursor to the Solidarity movement.) However, this film was from the earlier period of Zanussi’s work, which was heavily influenced by the French New Wave. In fact, he first became known through interviews and on set-reports from the films of some of the key figures of the Nouvelle Vague in the 1960s. Nevertheless, even these early films by Zanussi have tended to be seen in terms of their content rather than their form and thereby assimilated into the later movement that was perhaps sealed by Zanussi’s appearance in Kislowski’s Camera Buff (Amator, 1979) in which questions of social reality and engagement are prioritised by Zanussi, appearing as himself, over questions of cinematic form.

Illumination, seen in a New Wave context, is most remarkable for its fusion of documentary and fictional techniques in which the everyday life of aspiring scientists is presented both through the narrative of the conflict between the main character’s desires to understand the world scientifically and his ever-increasing responsibilities to his wife and child. Beginning with a University professor, W?adys?aw Tartarkiewicz, theoretically defining the experience of rational illumination, the film presents a series of obstacles in the life of its protagonist in actually achieving any such illumination. More importantly it does so by interspersing the scenes of informal discussions between young scientists, scientific diagrams, photos and other documentary phenomena within the fictional world of the film, constructing an essayistic form that highlights the ethical issues and conflicts between individual achievement and social responsibility facing the protagonist. As interesting as the film is formally, however, the latent conservatism and anachronism of the issues it presents are hard to disentangle from the director’s future evolution not only as a key participant of the cinema of moral concern but also as the director of a hagiography of Pope Jean-Paul II. Nevertheless on a formal level the film was fresh, original and deeply affecting.

The final screening was composed of three films that have to be separated into two totally distinct aesthetic projects: that of creative documentary and the generic superhero pastiche of Andrzej Kondratiuk’s The Hydro-Riddle (Hydrogazadka, 1970). The first of the creative documentaries, Skiing Scenes with Franz Klammer (Sceny narciarskie z Franzem Klammerem, 1980), is a formally constructed work that departs from most norms of documentary cinema. Every scene in the film is artificial and staged and the film points comically to its own production in an early and comic self-referential scene of various takes of filming Klammer on the snow. In fact, despite the title, this is one of the few scenes that actually involves any skiing. The rest of the film, on the contrary, constructs an impressionistic and surreal account of Klammer’s life culminating in him appearing at an opera house, acrobatically leaping in the air as an allegorical exhibition of his skiing prowess, transformed into a cultural arena.

The final screening was composed of three films that have to be separated into two totally distinct aesthetic projects: that of creative documentary and the generic superhero pastiche of Andrzej Kondratiuk’s The Hydro-Riddle (Hydrogazadka, 1970). The first of the creative documentaries, Skiing Scenes with Franz Klammer (Sceny narciarskie z Franzem Klammerem, 1980), is a formally constructed work that departs from most norms of documentary cinema. Every scene in the film is artificial and staged and the film points comically to its own production in an early and comic self-referential scene of various takes of filming Klammer on the snow. In fact, despite the title, this is one of the few scenes that actually involves any skiing. The rest of the film, on the contrary, constructs an impressionistic and surreal account of Klammer’s life culminating in him appearing at an opera house, acrobatically leaping in the air as an allegorical exhibition of his skiing prowess, transformed into a cultural arena.

The whole film plays on the kitsch aspects of Austrian culture and concentrates less on trying to present a coherent reality than on the iconography surrounding the figure of Klammer, which is nonetheless highly expressive and idiosyncratic. A similar displacement of reality is evident in the next film presented: Wanda Go?cimi?ska: A Textile Worker (Wanda Go?cimi?ska: W?lokniarka, 1975), this time through a disjunction between sound and image. While the voice-over consists of the protagonist, Go?cimi?ska, reading her biography, the scenes that accompany her narrative are staged visual illustrations of the life events she is describing, effectively creating a kind of personal iconography rather than normatively situating the real character in its environment as wouldbe typical of biographical documentaries.

The final film, Andrzej Kondratiuk’s The Hydro-Riddle was clearly the most popular film of the weekend and the Starr theater swelled to capacity with audience composed largely of young Poles who certainly responded more vocally to this film than to the documentaries. This is hardly surprising considering the broad intertextual humour that distinguished Kondratiuk’s film form the rest of the season. This humour is immediately apparent in this film when, in the place of any normal title sequence, the titles are not only spoken but dramatically performed by the actress Iga Cembrzynska, a performance full of speeding up and slowing down, facial tics and sudden shifts in intonation, gesture and affect, which is a hyperbolic version of a technique originally employed by both Truffaut and Godard, thus giving the film a Nouvelle Vague intertextuality.

The final film, Andrzej Kondratiuk’s The Hydro-Riddle was clearly the most popular film of the weekend and the Starr theater swelled to capacity with audience composed largely of young Poles who certainly responded more vocally to this film than to the documentaries. This is hardly surprising considering the broad intertextual humour that distinguished Kondratiuk’s film form the rest of the season. This humour is immediately apparent in this film when, in the place of any normal title sequence, the titles are not only spoken but dramatically performed by the actress Iga Cembrzynska, a performance full of speeding up and slowing down, facial tics and sudden shifts in intonation, gesture and affect, which is a hyperbolic version of a technique originally employed by both Truffaut and Godard, thus giving the film a Nouvelle Vague intertextuality.

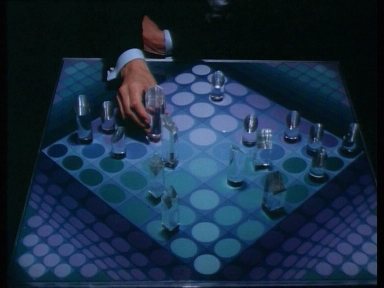

What follows, however, is clearly an appropriation of American pop culture in a Polish context, specifically of the superhero cartoons such as Superman and Batman well before their Hollywood reappraisal of the 1980s and despite the unavailability of these examples of “Western propaganda” in the People’s Poland. The film’s protagonist, Ace (As), like Superman’s Clark Kent, is a bespectacled everyman, to a certain degree, even a village idiot, whose superhuman capacities are unsuspected by his neighbours. Ace is called out of obscurity to defeat Dr. Plana’s evil plan, which involves an absurd pseudo-scientific scheme to steal the Polish water supply through nuclear-generated evaporation in order to transport it in cloud form to a Middle Eastern nation whose “Maharajah” is scheming with the evil doctor. The absurdity of the comic book story is only exaggerated by its transposition into the quotidian reality of the People’s Republic of Poland. In one memorable scene, As criticises the station manager for falling asleep and thereby violating the rules of conduct for state rail employees. Throughout the film, As continually upholds rules and regulations, however absurd they might be. In this way the film’s intertextuality extends to both the products of American pop culture and Polish propaganda, through a gentle but still subversive ridicule of the absurdities of both.

As will be evident from this review, the films that constituted the Polish New Wave event showed a remarkable diversity and presented a variety of innovative approaches to film form, each with different implications and ways of addressing the viewer. Nevertheless, most of these films still felt very fresh aesthetically and had a consistency in their search for new cinematic languages adequate to the expression of life in modern Poland from the 1960s and despite the very real difficulties of censorship and exclusion that almost all of these filmmakers faced as a result of these explorations of cinematic form. In fact it can be argued that the non-existence of a stable Polish New Wave movement was entirely due to this repression of these new forms of cinematic expression, that often forced filmmakers to choose between exile and aesthetic and political conformity so that instead there are only fragments of a New Wave that never was, as the title of the retrospective suggested.

Nevertheless the strength and consistency of selection of these fragments indicates that the atemporal construction of the Polish New Wave that the curators are proposing has a critical validity that is even further reinforced by the publication of the excellent bilingual book, entitled simply Polish New Wave/Polska Nowa Fala that accompanied the screening of the films and has certainly informed this review. One can only hope that there will be more events of this quality related to Polish film history in the future. And that we will have the kind of high-quality research and presentation of the Polish New Wave to which this event was an introduction. Columbus-deluxe-777.com has all the slot games you will ever need!